4.3 Value creation

Digital health innovations are altering many aspects of health and social care with potential to transform care and care delivery to support a person-centred approach (Almond & Mather, 2023). Further transformation requires changes in leadership, culture and ways of working to support the effective adoption of health information systems and technologies.

Health and social care services rely on the collection and sharing of data for the care of patients in hospitals and residents in aged care. This same data is also critical for the monitoring of safety, quality of care, and organisational performance and accountability. Information technologies have traditionally been used in these settings to help with the collection of data, often from a transactional perspective. The digital world of the 21st century offers the opportunity to apply information technologies beyond transaction-based solutions to generate value from these rich datasets. The value gains may be in research through data mining, through better health outcomes from shared data across a person’s lifetime or through true real-time monitoring of safety and quality of care and improved system monitoring. EMRs, for example, have been widely adopted in Australia and other countries. Globally, much of the data we collect is underutilised due to a variety of reasons, including a perception that it is not relevant or reliable to inform decision-making. According to the World Bank (2023), despite technological progress and data availability, health policy decisions in many countries are not always based on reliable data. Further they estimate that some countries use less than 5 per cent of health data to improve health (World Bank, 2023).

Telehealth and remote monitoring

Telehealth and remote patient monitoring have been widely adopted, extending access to a scarce health workforce, particularly in rural and remote locations. However, we have also seen an explosion of telehealth and remote monitoring in large metropolitan centres as approaches to avoid hospitalisation and to support a more person-centred approach. In NSW, the virtualKIDS urgent care service, developed by the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network now provides a statewide service for children up to 16 with non-life-threatening health concerns (McDonald, 2024a). virtualKIDS connects families with a triage nurse who then determines the best care pathway and care provider. They triage children to the emergency department, when necessary, for a consultation with a virtualKIDS paediatrician or a visit to their local GP or urgent care centre (McDonald, 2024a).

Data analytics

Big data and analytics for predictive healthcare and artificial intelligence (AI) are emerging areas with potential to predict underlying health conditions and initiate preventative treatments or plans. Using advanced techniques and machine learning, vast amounts of healthcare data can be analysed. Analytical tools identify patterns, correlations and individuals at risk of disease; care plans can be personalised and early intervention and treatment initiated. AI is now routinely embedded in many software packages and used to support clinical decision-making, such as medical image analysis, where algorithms can interpret MRIs and X-rays with high precision, aiding clinicians in making accurate diagnoses. AI is being integrated into a widely used medication management app (MedAdvisor) so that support on medication use can be provided to patients 24/7. This kind of tool can avert dosage or other errors relating to the correct timing and use of prescribed medications. Medication adverse events and poor compliance are costly to the health and social care system and impact on treatment efficacy. Naïve chatbots will be replaced with conversational AI to enhance the consumer experience and provide accurate and personalised education about medication (McDonald, 2024b).

Better value healthcare

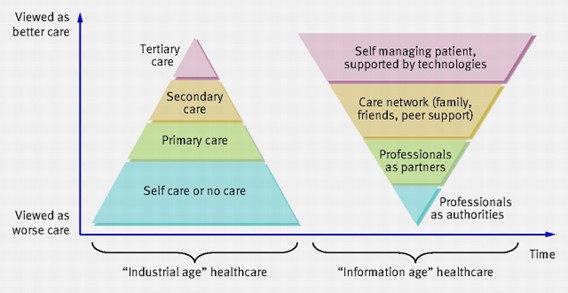

We have already described that interoperability, integration and standards help to create efficiency, data sharing, secure messaging and value. They support data collection, management and storage, ensuring that there is a common understanding of concepts and processes for data management. In the discussion above we have identified ways that AI, telehealth and other applications can improve diagnosis, predict and prevent illness. The current challenges in health and social care suggest that a major shift is required, from disease-focused models of care to informed, self-managing patients who actively direct their healthcare (Greenhalgh et al., 2010). New models of care can be enabled through electronic healthcare records (longitudinal summaries across a lifespan from cradle to grave) extracted from EMRs (organisational records) that link to personally held records that are shared with treating clinicians to maintain continuity of care (Greenhalgh et al., 2010). Specific examples of how health and information technologies can transform low-value healthcare to better value healthcare include:

- Patient safety: improved monitoring using digital real-time devices that alert clinical staff to the need for earlier intervention of disease processes;safer medication practices that reduce the potential for error and waste

- Resource efficiency and effectiveness: better resource scheduling (human and physical); bed management software that supports improved bed and staff utilisation

- Cost management through improved resource management and utilisation: often achieved through waste reduction (physical and time)

The case studies in the following section provide further examples of how health and digital technologies can transform low-value situations into better value and better outcomes.

Figure 4.2 (Greenhalgh et al. ,2010) illustrates the transformative impact of this shift, creating parity between patients and health providers and putting health information into the hands of individuals. With the ability to hold personal health information, individuals can take a more active role in their healthcare. Information age healthcare also signals a change in the role of health providers from authorities of care to partners and facilitators of care. For example, if a chronic disease is diagnosed, the recipient of the diagnosis would be referred to a specialist team who would provide education, management tools for their condition and monitoring devices. Regular monitoring and alerts in home and treatment settings can flag with consumers and healthcare professionals when intervention is required.

Source: Fig. 1 in Greenhalgh et al. (2010). Adoption, non-adoption and abandonment of an internet-accessible personal health organiser: Case study of HealthSpace. BMJ, 201, c5814. Used under CC BY 4.0.

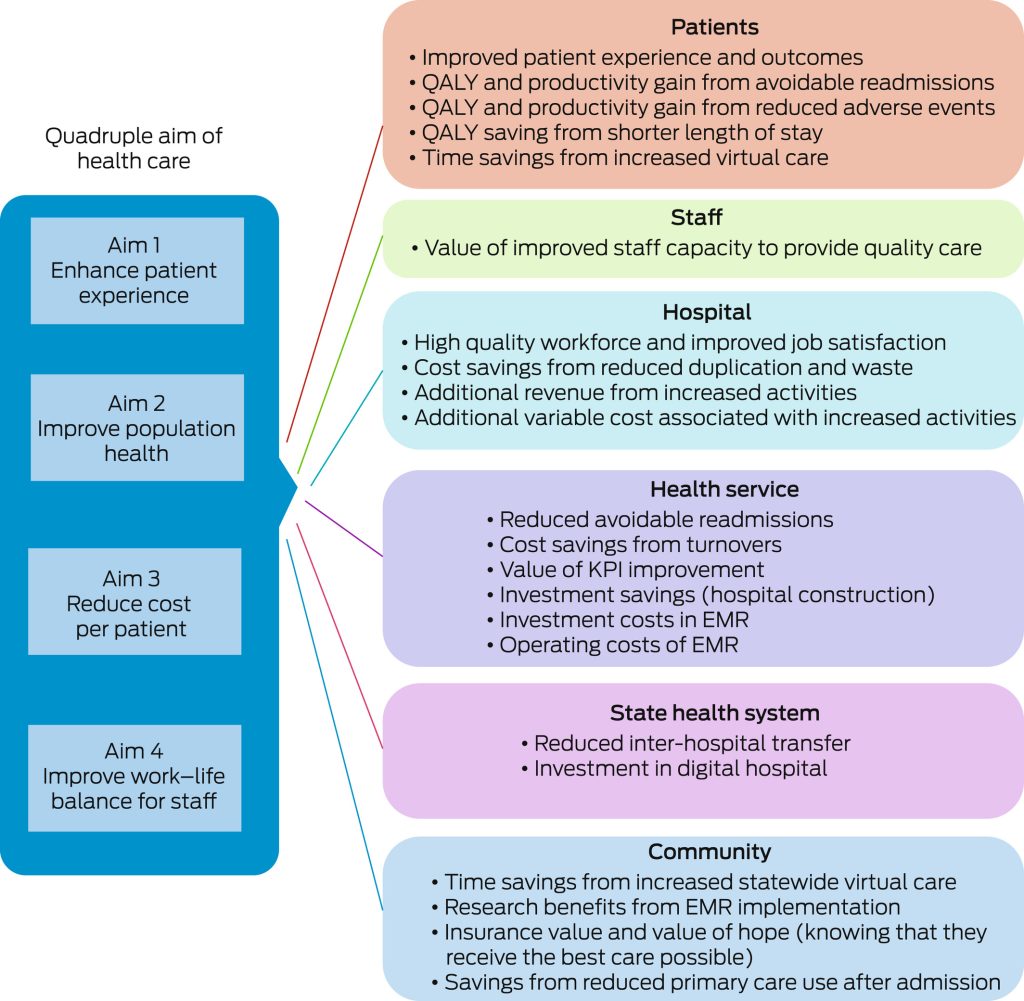

When considering the acquisition of digital health tools or health information systems, benefits to consumers and the health and social care system must outweigh costs. In health it can be difficult to quantify and comprehensively capture the value and benefits from investment in digital health solutions, such as workforce satisfaction, savings from averted hospital admissions and improvements to safety and quality (Woods et al., 2023).

Focusing solely on financial measures is unlikely to deliver a comprehensive view of the value of digital health.

(Woods et al., 2023)

Figure 4.3 shows a mapping of improvements that can be generated from EMRs and mapped against Woods et al.’s (2023) ‘quadruple aim’ for health.

Source: Box 3 in Woods et al. (2023). Show me the money: how to we justify spending health care dollars on digital health? Medical Journal of Australia, 218(2), 53–57. Used under CC BY 4.0.

ACTIVITY