3.3 Types of models

For a health system predominantly funded through government revenue, there is little difference between ‘funding’ and ‘payment’. But in health systems with mixed funding sources, funding may mean different things to payment. Value-based care needs to be enforced through funding mechanisms imposed by large funding bodies on behalf of consumers, while consumers share expenses through ‘out-of-pocket payments’, which are unlikely to be linked to value-based care. The following eight models represent a variety of funding models that are used internationally.

Fee-for-service

Fee-for-service (FFS) represents a traditional payment approach widely used in the global healthcare sector. Under this system, healthcare providers are reimbursed by government organisations or insurance providers for specific services rendered to patients. The quantity of services and procedures requested by the patient directly influences the remuneration received by the healthcare provider (Miller-Breslow & Raizman, 2020). Payments are disaggregated, with each service or item billed and compensated for separately. Consequently, whether it involves a doctor’s appointment, patient consultation or hospital admission, each instance of service provision results in individual billing by the respective agency or insurer. This method of payment has been used as the main compensation for providers for a long time. However, it can be thought of as an incentive system for providers to encourage more treatment for patients, resulting in more income.

There are several advantages of this type of care, including that access to care is guaranteed for patients, patients get to choose their procedures from a variety of treatments and the type of management can ease the burden of cost on patients. Disadvantages of this type of care include potential of out-of-pocket expenses for patients, lack of cover of preventative treatment, absence of accountability of medical providers and patients, and lack of awareness of the real costs of treatment for patients and providers (Brekke et al., 2020). FFS also encourages overservice/waste and low-value care, but governments can remove or de-incentivise low-value care through fee schedules.

The following example demonstrates how FFS could be applied to show either a profit or a loss. In general, hospitals have two types of costs: fixed and variable. Fixed costs include equipment, staff salaries and administrative overheads; variable costs include patients treated, medications and contracted labour.

Hospitals structured on a FFS basis experience financial gains with higher patient volumes but face losses during periods of decreased volume. In Table 3.1, scenario 1 shows the profit when the hospital experiences a 5 per cent increase in hospital admissions; scenario 2 shows the loss from a 5 per cent decline in admissions. Clearly, FFS funding is profitable when the number of patients treated increases, and it runs at a loss when the service experiences a decrease in number of patients managed.

Table 3.1: FFS model on two scenarios

| Base | Scenario 1 (5% increase in admissions) |

Scenario 2 (5% decrease in admissions) |

|

| Fixed cost | $100 m | $100 m | $100 m |

| Variable cost | $100 m | $105 m | $95 m |

| Total costs | $200 m | $205 m | $195 m |

| Revenue | $205 m | $215.25 m | $194.75 m |

| Profit (Loss) | $5 m | $10.25 m | (–$250,000) |

Capitation

Managed care organisations employ capitation payments as a strategy to manage healthcare expenditures. These payments assign financial responsibility to physicians for their services to patients, thereby curbing the utilisation of healthcare resources. Simultaneously, to safeguard against potential underutilisation of healthcare services leading to substandard care, managed care organisations monitor resource utilisation rates within physician practices. These utilisation metrics are publicly disclosed as indicators of healthcare quality and may be tied to financial incentives such as bonuses (Basu et al., 2017).

Capitation entails a predetermined sum of money per patient per specific time period, provided upfront to physicians for delivering healthcare services. The actual payment amount is determined based on the range of services rendered, the patient population and the length of service. Capitation rates are established using local cost data and average service utilisation rates, hence exhibiting much regional variation. Many plans incorporate a risk pool, retaining a portion of the capitation payment until the end of the financial year. If the health plan functions well financially, these withheld funds are disbursed to physicians; conversely, in the event of financial underperformance, these funds are retained to cover deficit expenses (Andoh-Adjei et al., 2018).

A capitation agreement with healthcare providers lists the services to be provided for patients; for example, preventative and diagnostic treatments, immunisations, outpatients laboratory tests, health education and screening for vision and hearing. The amount of remuneration is based on the average expected healthcare utilisation of patients with certain medical comorbidities and demographic factors. The disadvantage of this model is that providers can end up treating more than the average number of patients specified in the agreement, resulting in a loss for the organisations (Basu et al., 2017).

Capitation may lead to underutilisation of high-cost care with high value. It may take several years to demonstrate value of care and annual capitation if funding cannot capture such value. The pros and cons of this model are outlined in this analysis.

Global budgeting

A global budget is a mechanism that assigns a set number of resources for the healthcare sector as a whole, rather than for specific individuals or organisations. Its primary objective is to regulate overall healthcare expenditure and ensure reasonable and affordable healthcare services. Global budgeting serves as a supplementary payment approach that can be integrated with other payment methods to create a framework adaptable to diverse contexts. The primary distinction among different schemes lies in the mechanism used to enforce the budgetary limit on the healthcare system (Lin et al., 2016). A study by Lin et al. (2016) examining the impact of global budgeting in Taiwan on healthcare utilisation found this funding model is associated with a significantly longer length of stay in hospitals, higher healthcare costs and poorer quality of care among patients with pneumonia.

Global budgets overcome the tendency of itemised payment systems to encourage higher volumes by broadening the scope of covered services. Unlike other payment methods that bundle services – for example, episode of care payments that encompass all hospital care for knee replacement patients, including the 30 days before and after hospitalisation – hospital global budgets offer supplementary incentives and avenues for controlling volumes and costs. This framework provides hospitals with distinct motivations to oversee their care provision within a predefined budgetary limit, thereby highlighting the policy goal of containing costs. Cost-saving measures from global budgeting can lead to risk shifting (e.g. cream skimming) and care delay. Exhibit 1 from this paper shows how global budgets are calculated based on a broader range of items for each diagnosis-related group (DRG) (Sharfstein, 2016).

Global budgets incorporate incentives aimed at encouraging hospitals to adopt strategies for care coordination, along with enhancing the overall health of patients. These initiatives, in turn, contribute to minimising hospitalisation. A hospital operating under a global budget that directs investments toward community-based programs emphasising care coordination, improved access to primary care providers and early intervention for chronic illness is likely to experience decreased costs and savings within the scope of its global budget, if the calculation is done appropriately (Porter, 2013).

Pay for performance

Pay for Performance (P4P) incorporates payment frameworks that combine financial incentives or penalties to provider performance. P4P forms a crucial component of the wider initiative aimed at transitioning healthcare towards value-based healthcare. Although it operates within the FFS system, P4P encourages providers to embrace value-based care by combining compensation to measurable outcomes, evidence-based practices and patient satisfaction. This approach aligns payment structures with the delivery of value and high-quality care (Mendelson et al., 2017).

There are several advantages of P4P, including a focus on quality rather than quantity, promoting good clinical practice and focusing on positive outcomes. It also encourages transparency, as it reports on metrics that are usually publicly available in annual reports and therefore encourages good clinical practice. One of its disadvantages is that it does not necessarily cater for socio-economically disadvantaged populations, as they usually require higher care than the average patient, which may prompt some organisations not to manage them. These types of patients may struggle to follow advice regarding their health management due to factors including the affordability of medication and transport, and fallback on follow-up appointments, resulting in poorer health outcomes. Goal displacement is also a disadvantage of P4P, where health providers try to achieve performance goals set by funding bodies, rather than maximising value for patients (Mendelson et al., 2017).

For P4P to function appropriately for all types of patients, health leaders must devise appropriate patient management metrics and highlight the physician–patient relationship, evidence-based best practices and performance measures (Soucat et al., 2017). When designing programs, healthcare executives need to prioritise strategies that tackle the social determinants of health and incorporate measures promoting fairness to ensure equitable comparisons among providers. Additionally, they should incentivise clinicians and hospitals that demonstrate excellent performance in serving socio-economically disadvantaged patient cohorts, thus moderating the financial risks associated with caring for these populations.

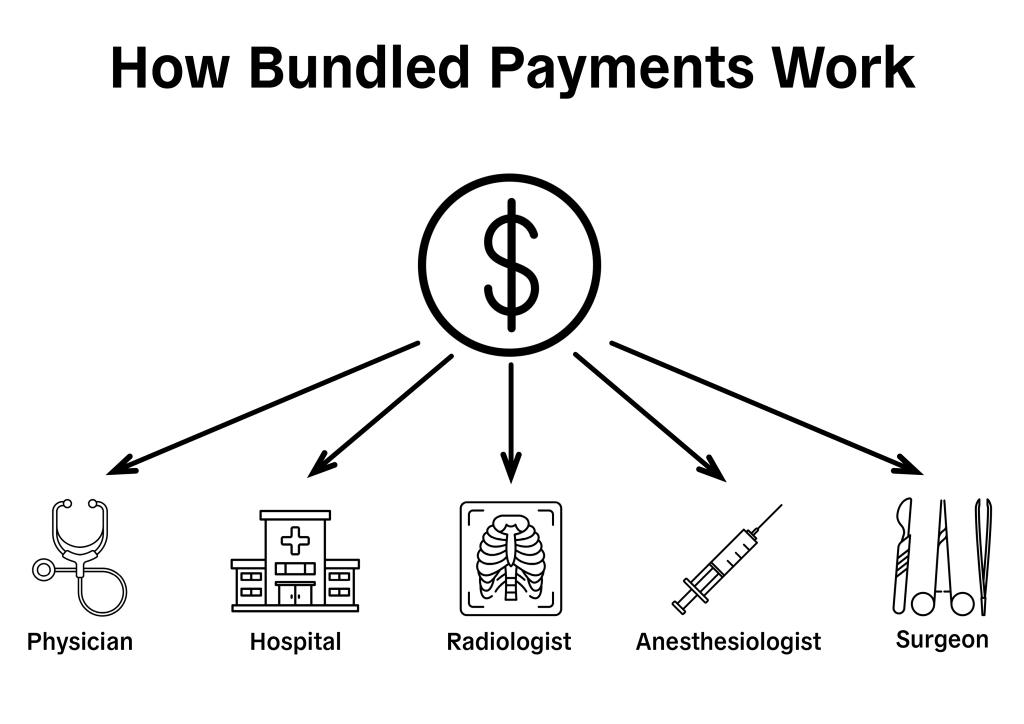

Bundled care payment

Bundled care payment (BCP) is used as a means to lower costs. Under BCP, payments use a set fee based on an episode of care. Bundled-payment models take advantage of provider imperatives to manage budgets and ensure high-quality care. Healthcare organisations receiving bundled payments stand to benefit from increased profitability when patients require fewer services. However, they must also account for unexpected utilisation and complications, which can impact their financial bottom line. Public and private payers in numerous countries are embracing this type of payment in the belief that incentivising providers financially to prioritise value may yield better outcomes compared to placing financial burdens on patients through out-of-pocket expenses (Baicker & Chernew, 2017).

Most BCPs focus on chronic conditions with specific numbers of treatment days. For instance, for diabetes care bundles in the Netherlands a treatment plan spans 365 days. Conversely, bundles covering procedures such as total joint replacement (TJR) define the treatment plan in terms of the period of illness or treatment cycle. In TJR bundles, this episode encompasses preoperative, inpatient and post-discharge phases, with varying durations for each phase. The quantification of episodes in TJR bundles show considerable variation; for instance, in the BPC model, the post-discharge period is capped at 180 days (Miller-Breslow & Raizman, 2020; Struijs et al., 2020).

Payers and providers have two primary options for payment flow strategies: (1) a pre-established price as a single payment to the accountable entity upfront; or (2) upfront FFS payments to individual providers (Miller-Breslow & Raizman, 2020). This type of payment has shown significant improvement in quality of care to patients and cost reduction to organisations, but challenges include the difficulty in defining patient populations for the bundled care, defining quality of care, and privacy laws and information sharing (Struijs et al., 2020).

Figure 3.2 shows how a bundled payment might work for a surgical procedure. The provider is paid a lump sum for all the services in a given episode; reimbursement is withheld for costs in excess of that amount.

Value-based purchasing

Value-based purchasing (VBP) is a healthcare payment model that ties financial incentives and reimbursements to the quality of care provided by healthcare providers. In a VBP system, healthcare purchasers, such as government payers, insurance companies or employers, use various quality measures and performance metrics to assess the value of healthcare services delivered by providers. Providers are then rewarded financially for delivering high-quality care and achieving positive patient outcomes, and face penalties for underperformance or low-quality care (Chee et al., 2016). VBP focuses on patient outcomes, satisfaction and overall quality of care rather than just the volume of services provided.

Providers are evaluated based on value metrics, such as patient satisfaction scores, clinical outcomes, adherence to evidence-based practices and efficiency measures. Providers are financially incentivised for meeting or exceeding quality benchmarks and achieving positive outcomes. Conversely, they may face financial penalties for poor performance or failure to meet quality standards. VBP rewards healthcare providers based on the quality and efficiency of care delivered, as measured by various performance metrics and patient outcomes. It typically involves a broader range of services and performance measures beyond specific episodes of care than bundled payments, where the focus is on reimbursing providers a single, predetermined payment related to a specific episode of care.

While VBP has several advantages for patients and providers to improve quality of care, the biggest challenge is that these programs often require significant administrative resources for data collection, reporting and performance monitoring. This can impose additional administrative burdens on healthcare providers and organisations, particularly smaller practices or facilities with limited resources. Moreover, providers in VBP programs may bear financial risk if they fail to meet performance targets or if patient outcomes are poorer than expected. This risk can deter participation, particularly for providers caring for high-risk or complex patient populations (Chee et al., 2016). The following video outlines VBP and how it is calculated.

VIDEO: WHAT IS VALUE BASED PURCHASING?

Source: AHRMM (4 mins)

Accountable care organisations and shared savings programs

An accountable care organisation (ACO) is a delivery model of care that seeks to progress the quality of healthcare provided and limit costs. In an ACO, a group of healthcare suppliers, including hospitals, physicians and other healthcare professionals, voluntarily come together to collaborate and coordinate care for a specific patient population (Miller-Breslow & Raizman, 2020). They are often accountable for the overall health outcomes and expenditures of the patient population they serve. Their main goals are to focus on managing the health of their entire patient population, not just individual patients. This includes preventive care, chronic disease management and addressing social determinants of health to improve overall health outcomes and reduce healthcare utilisation. They engage patients in shared decision-making, promote patient education and self-management, and emphasise the importance of communication and continuity of care.

ACOs often participate in alternative payment models, such as shared savings or shared risk arrangements, where they may receive financial incentives for meeting quality and cost targets or may be accountable for financial losses if they exceed predefined spending thresholds (Shortell et al., 2015). The performance of ACOs varies, as they are dependent on multiple factors such as providers’ understanding of and commitment to care coordination and successful integration of processes within organisations (Comfort et al., 2018).

Time-driven activity-based costing

Within value-based healthcare, costs are ideally assessed using time-driven activity-based costing (TDABC). With TDABC, the actual costs incurred in delivering care to patients with specific conditions are meticulously calculated from the ground up, scrutinising each step of treatment and the associated costs of each process involved. TDABC methodology aids in pinpointing opportunities for cost reduction and determining the appropriate pricing for procedures (Keel et al., 2017). It has been presented as a better way to measure the cost of care, as it adapts to the complications of care provision in healthcare organisations. In 2011, Robert Kaplan and Michael Porter detailed a seven-step approach to the application of TDABC in healthcare settings:

- Select the medical condition

- Record all the main activities performed within the entire care cycle

- Develop process maps that include each activity in patient care delivery, including all direct and indirect capacity-supplying resources

- Obtain time estimates for each process

- Assess the cost of supplying patient care resources

- Assess the capacity of each resource

- Calculate the total cost for each patient

(Porter & Kaplan, 2011)

TDABC calculates the direct and indirect costs of care for patients; however, it may be seen as complex due to the number of steps involved in and the various methods of calculation (da Silva Etges et al., 2020).