18 When penguins were giants with spear-like bills

Aves, Sphenisciformes: Kairuku grebneffi and K. waitaki

The emperor penguin Aptenodytes forsteri is the largest species of penguin living today at around one metre tall and weighing up to 40 kg. Penguins have a long and relatively detailed fossil record with much of our knowledge of penguin history coming from discoveries made in New Zealand. These include two species of ‘giant’ fossil penguin first described in 2012, Kairuku grebneffi and Kairuku waitaki. In life these ‘giants’ would have been another 30 cm taller than an adult emperor penguin.

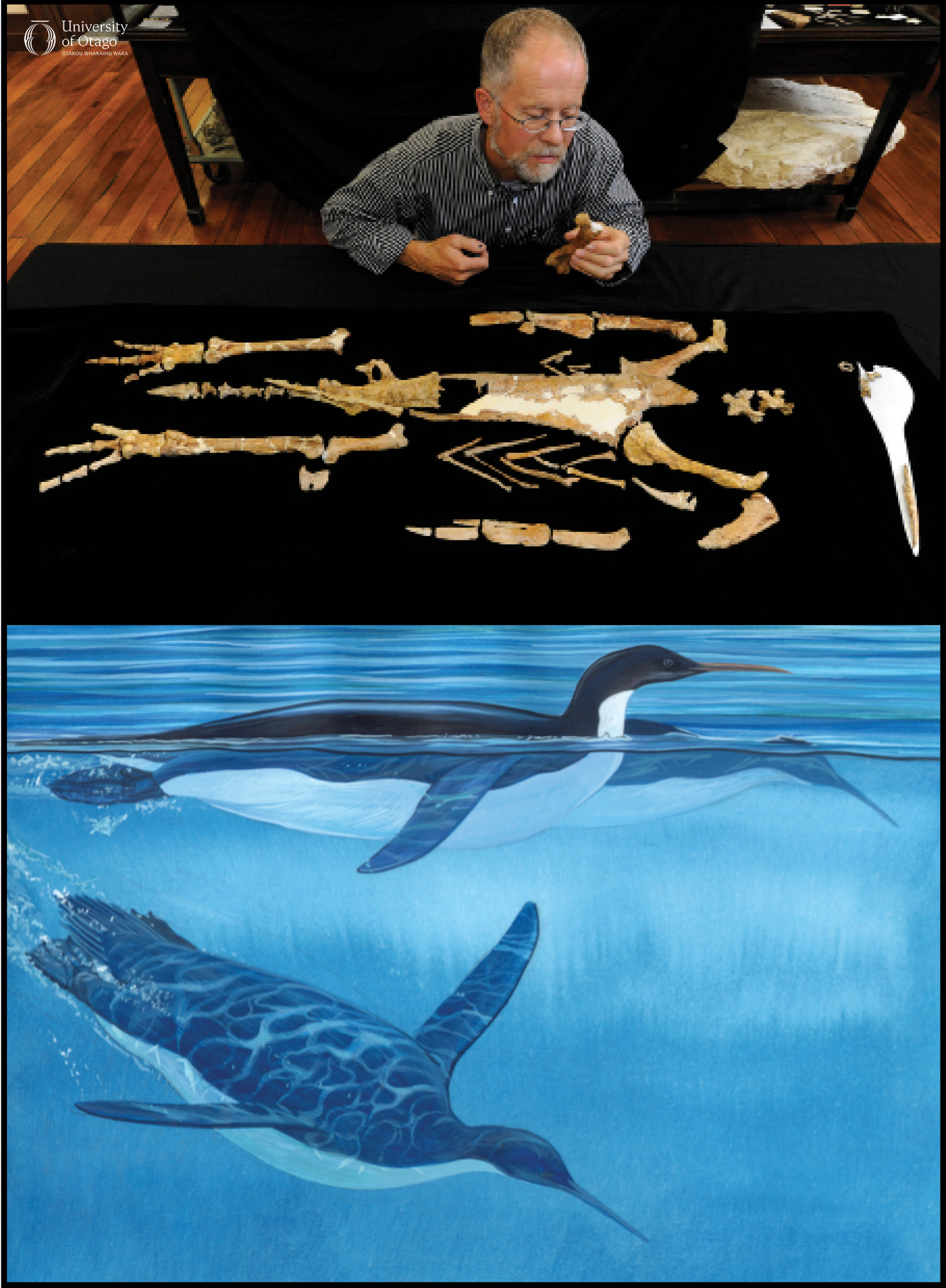

In the upper image R. Ewan Fordyce examines a composite skeleton of bones assembled from two species of Kairuku fossil penguin. The lower image is a reconstruction of Kairuku swimming in late Oligocene oceans. Image credit: RE Fordyce (photograph), C Gaskin (illustration). |

At least five partial skeletons of Kairuku penguin are housed in the University of Otago Geology Museum. All are from Kokoamu Greensand near Waimate in South Canterbury and Duntroon in North Otago. Each partial skeleton has its own museum accession number. The partial skeleton that became the holotype for Kairuku waitaki has the accession number OU 12652, and the partial skeleton that became the holotype for Kairuku grebneffi has the accession number OU 22094. The Kairuku specimens in the Geology Museum owe their discovery to Ewan Fordyce. In Ewan’s words:

“…I found the first Kairuku penguin when I was a PhD student, in 1977, on a field trip looking for Oligocene fossil whales and dolphins near Waimate. One distinctive oval bone was exposed – a broken section through the tibia, or lower leg bone. I collected a few fragments, but realised that the fossil was big, and would take some time to collect – and I didn’t have the time or money to do more work. Then I went overseas to study. The penguin stuck in my mind and, when I returned to take up a job at University of Otago, I returned to the site – and found things exactly as I had left them 4 years earlier. So, I excavated the specimen fully…”

When they were described the Kairuku penguins were amongst the most complete fossil penguin skeletons known and included bones from the tip of the bill through to the feet. These specimens allowed researchers to reconstruct the shape of the body of extinct giant penguins and estimate their size.

From a distance, Kairuku penguins would have looked similar to modern species like the emperor penguin. Up close though you would see that both Kairuku waitaki and Kairuku grebneffi had relatively longer bills and a more slender body than living species. The wing was relatively longer than in living species and could flex a little more at the elbow.

There are several possible explanations for large body size in extinct penguins. Large size could have been an adaptation for long-distance swimming and for deep diving. Studies of marine organisms in general suggest that bigger forms can swim more efficiently than smaller forms and thus might be able to feed on rich food resources further from land. Alternatively, large size might have been an adaptation against large predators.

Kairuku penguins probably swam far out to sea, beyond the limits of the wide shallow seas of Zealandia, then dived into deep water to search for prey. Prey was likely fish and squid. The long beak would suggest a spearing and snapping behaviour. In turn, the penguins could have been hunted by early dolphins, especially forms with short, robust, and heavily toothed jaws. Like some species of the shark-toothed dolphins (Squalodontidae) that are also within the collections of the Geology Museum.

—Written by Daniel B Thomas

| Specimen number: OU 12652, OU 22094 | Age: Approximately 26 million years old (late Oligocene, Duntroonian stage) |

| Locality: Duntroon, North Otago | Rock Formation: Kokoamu Greensand |

| Collected by: RE Fordyce, MA Fordyce | |

| Citation: Ksepka DT, Fordyce RE, Ando T, Jones CM. 2012. New fossil penguins (Aves, Sphenisciformes) from the Oligocene of New Zealand reveal the skeletal plan of stem penguins. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 32:235–254. doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2012.652051 | |

Penguins. An order of seabirds with around 20 living species in a single family (Spheniscidae). Many more extinct species of penguin are known compared with the number of living species.

A collection of fossils that document the history of life. Reference might be made to the history of life in a particular place ('the fossil record of New Zealand'), or the history of a particular group of organisms ('the fossil record of penguins'), or simply the global history of all life ('the fossil record').

Evidence of life from a past geological age. Remains like bones, shells or wood, or an impression like a footprint, or some other evidence of life, from something that was alive more than 11,700 years ago.

Green-grey, calcareous, glauconitic, quartz sandstone.

The individual specimen from which a species is named.

33.9 to 23.03 million years ago.

Bone in the lower leg of a bird. This bone is a fusion of the tibia and elements of the tarsal bones that would be found as separate bones in some other reptiles or in mammals.

The mostly submerged continent of which New Zealand and New Caledonia are a part.