29 Alexander McKay’s pencil urchin

Echinodermata, Echinoidea, Cidaroidea: Histocidaris mckayi

Cidaroids are a group of regular echinoid echinoderms that are commonly known as ‘pencil urchins’ for their thick and rounded spines. Cidaroids are free-living and have a globe-shaped test with the mouth centrally placed on the lower surface. When viewing a cidaroid from the lower surface you can see that the test is arranged into five regularly-spaced groups of plates. This regular arrangement makes each cidaroid a great example of the pentaradial symmetry for which echinoderms are known. The plates making up the test of a cidaroid support their distinctively thick spines on large circular bases. However, the animal only moves about on small tube feet that emerge from tiny rows of pores. As a result, cidaroids have limited ability to move around on the sea bed or to hold on to the substrate, unlike other echinoids that have thinner spines and longer tube feet.

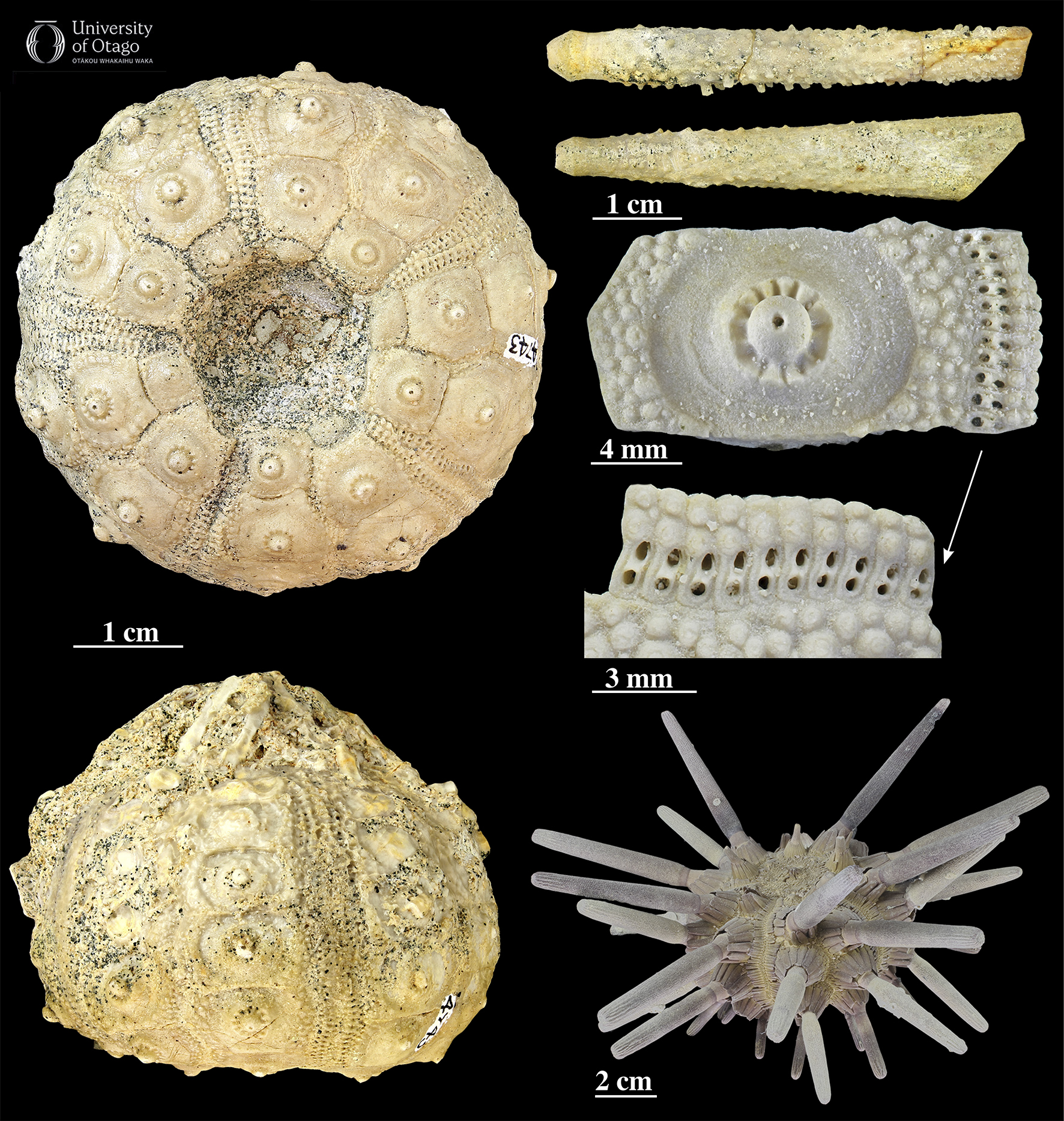

The outer shell (also called a ‘test’) and spines of the pencil urchin Histocidaris mckayi, and the test of a modern pencil urchin for comparison. The images on the left show two views of the holotype (specimen OU 4743), revealing how the test is made up of multiple plates. The top right and middle right show spines and a plate from Histocidaris mckayi. The plate has a large central tubercle (bump) where a spine would have attached when the animal was alive. The smooth ring around the central tubercle in the plate is where the muscles that moved the spine would have attached. The plate also has smaller tubercles where other, smaller spines were attached. The double row of holes (pores) in the plate show where tiny tube feet would have emerged. The image on the lower right is a modern pencil urchin, possibly from the genus Prionocidaris, which shows what Histocidaris mckayi would have looked like in life. Image credit: JH Robinson. |

There are around 25 species of cidaroids placed in a dozen genera that live in seas around Aotearoa New Zealand today. Species from several of these genera have been in the region for many millions of years because they are found in the New Zealand fossil record, including Goniocidaris, Histocidaris, Notocidaris, Phyllacanthus, Prionocidaris and Stereocidaris. Examples of many of these can be found in the Geology Museum collections. Although relatively common as fossils in New Zealand mid-Cenozoic limestones and greensands, most cidaroids are represented only by fragmentary specimens, or by isolated plates or spines.

Only one fossil species of Histocidaris has been named so far: Histocidaris mckayi Fell, 1954, the holotype of which is part of the collections of the University of Otago Geology Museum.

Specimens of this distinctive cidaroid were collected in the early stages of geological exploration in New Zealand, as far back as 1866. These specimens are held in the collections of the New Zealand Geological Survey (now Earth Sciences New Zealand). The first mention in print of this species as “Cidaris” was made by Alexander McKay in the Reports of Geological Explorations in 1882.

It was first illustrated as a line drawing in 1886, although the fossil locality was mis-spelled as Waihoa (rather than Waihao), South Canterbury. The same illustration was included in figure 72 on page 140 of James Park’s The Geology of New Zealand published in 1910, where the specimen is listed as: “Cidaris, Sp. Nov. Waihao limestone”.

However, it took until 1954 for a formal species name to be applied to this fossil and echinoderm expert H Barraclough Fell placed it in the existing cosmopolitan genus Histocidaris. Fell refers to “the magnificent species described in the bulletin as Histocidaris mckayi”, the species name honouring Alexander McKay, one of New Zealand’s most prolific fossil collectors.

Histocidaris species today are regarded as benthic grazers in deep-sea environments: those found as fossils in New Zealand lived in mid-shelf environments, at much shallower depths, suggesting a change in ecology over the past 20 million years.

—Written by Daphne E Lee and Jeffrey H Robinson

| Specimen number: OU 4743 | Age: 25.4 to 24.4 million years ago (late Oligocene, Duntroonian stage) |

| Locality: Near Waihao Forks, South Canterbury | Rock Formation: Waihao Greensand |

| Collected by: CR Laws | |

| Citation: Fell HB. 1954. Tertiary and Recent Echinoidea of New Zealand. New Zealand Geological Survey Palaeontological Bulletin 23 | |

Not a parasite or attached to any other substrate.

The mineralised shell of some spherical organisms. For examples see foraminifera and echnioderms.

The surface of the test containing the mouth. This surface is often positioned towards the substrate. The opposite side of the test to the oral surface is the aboral surface.

Symmetry is a key feature in identifying animals, both living and fossil. Many, including humans, brachiopods and insects, exhibit bilateral symmetry, which is a body plan where an organism has a left side and a right side that are generally mirror images of one another. Cnidarians (corals and jellyfish) display radial symmetry, which is where the body is arranged regularly around a central point. Echinoderms are characterised by five-fold symmetry, also known as pentaradial symmetry. This is where, during a rotation around a central point, the body will appear to have a very similar outline at five different points during that rotation.

The taxonomic rank that groups together closely related species. The genus forms the first part of the binomial species name.

A collection of fossils that document the history of life. Reference might be made to the history of life in a particular place ('the fossil record of New Zealand'), or the history of a particular group of organisms ('the fossil record of penguins'), or simply the global history of all life ('the fossil record').

Evidence of life from a past geological age. Remains like bones, shells or wood, or an impression like a footprint, or some other evidence of life, from something that was alive more than 11,700 years ago.

66 to 0 million years ago. The Cenozoic Era is the section of geological history spanning the Paleogene and Neogene periods.

A sedimentary rock composed mainly of calcium carbonate. Can be formed from the skeletal fragments of marine organisms.

A marine sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized quartz and an abundance of the green mineral glauconite.

Hector J. 1886. Detailed catalogue and guide to the Geological Exhibits, New Zealand Court. Indian and Colonial Exhibition, London.

Park, J. 1910. The geology of New Zealand: an introduction to the historical, structural and economic geology. Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs.

Page 140 featuring Cidaris: Link provided by Papers Past, National Library of New Zealand.

Fell HB. 1954. Tertiary and Recent Echinoidea of New Zealand. New Zealand Geological Survey Palaeontological Bulletin 23

The extended margin of a continent which is submerged under relatively shallow seas. While the width of the shelf varies between continents, most shelf seas are generally less than 100 metres deep.