6 World’s oldest whitebait swam in volcanic lake

Osteichthyes, Galaxiiformes: Galaxias effusus

‘Galaxiid’ is the name often given to a distinctive Southern Hemisphere group of small to medium-sized freshwater fish (100 mm to 580 mm long as adults) that have no scales and lack an adipose fin. More than 20 species are currently recognised in the modern New Zealand fauna, but the exact number of species is a little unclear. The juveniles of five species that make up ‘whitebait’ were once abundant in many New Zealand streams, rivers, lakes and swamps, but are now under threat from habitat modification and overfishing. Local names for galaxiids include galaxias, mudfish, inanga or inaka (for Kāi Tahu) and kōkopu, amongst many other te reo Māori names used variously by iwi for adult and juvenile fish. The family name Galaxiidae refers to the small, silvery-gold star-like patterning seen on many galaxiid fish.

|

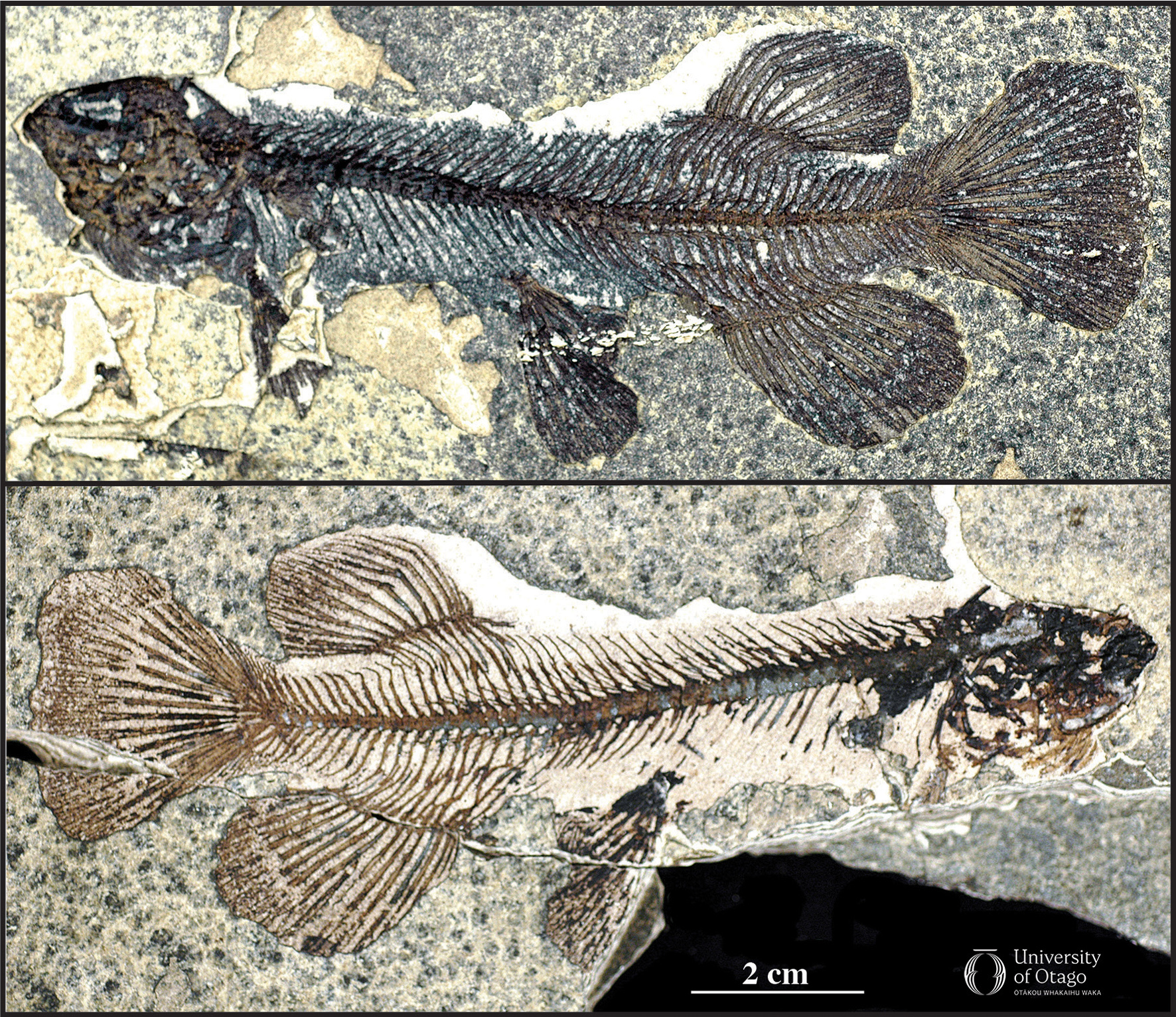

The part and counterpart of the holotype of Galaxias effusus (OU 22650). The 14 cm long fish was given the species name effusus because of the ‘lavish or extravagant’ fins compared to living species in the same genus. The original delicate fish bone material has been mostly dissolved (decalcified) and partly replaced by pyrite and brownish black residual material. Image re-use permission kindly provided by Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand and originally published in: Lee DE, McDowall RM, Lindqvist JK. 2007. Galaxias fossils from Miocene lake deposits, Otago, New Zealand: The earliest records of the Southern Hemisphere family Galaxiidae (Teleostei). Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 37:109–130. doi.org/10.1080/03014220709510540. |

Long considered to be of Gondwanan origin, galaxiids are found today in Tasmania, Australia, New Caledonia, South America, including the Falkland Islands, as well as New Zealand. In Aotearoa today, species occur from Northland to Stewart Island and as far afield as the Chatham Islands, Auckland and Campbell Islands. Most species are diadromous, spending the early part of their life cycle at sea before returning to freshwater environments to reproduce. A few species are land-locked and non-diadromous (from choice or chance) and their entire life cycle takes place in lakes.

Globally, the only known galaxiid fossils occur in lake deposits in Otago. The species Galaxias effusus found at Foulden Maar, at 23 million years old, is the oldest found so far. The best-preserved and most complete fish to be found at Foulden was effectively ‘filleted’ by a field knife splitting the laminated diatomite in which it occurred, with one side preserved on one layer and the counterpart on the other. The fish is more stout-bodied than most living Galaxias and differs from all modern species in its relatively low vertebral count, and expansive dorsal, anal and caudal fins.

More than 100 galaxiid fossils have now been collected from the two small Foulden mining pits; most are articulated, laterally compressed skeletons. They range from 40 mm larvae (whitebait) to 140mm long adults. Randomly dispersed throughout the exposed diatomite sequence, the little fish show no preferred orientation and no mass mortality layers have been observed. The exceptional preservation of soft tissue with eyes, skin and skin patterning is one of the reasons why the term Konservat-Lagerstätte is applied to Foulden Maar.

The stratified nature of the maar lake meant that only the upper few metres had sufficient oxygen for fish to thrive. The deeper bottom waters were anoxic so the fish may have succumbed to low oxygen levels if they swam down too far (many specimens died with gaping mouths). The lack of current activity and absence of bioturbation or scavenging at the bottom of the deep lake meant that the little fish remains lay undisturbed until covered by each successive seasonal rain of diatoms.

At Foulden Maar, the remarkable level of preservation allows us to identify the food of these 23 million year old fish. Living galaxiids in New Zealand are generalised invertebrate predators, eating beetles, moths and caterpillars, as well as aquatic insects including caddisflies, mayflies, midges and their larvae. Some of the Foulden fish have gut contents that preserve their final meal and indirect evidence for their food is abundant in the form of coprolites.

—Written by Daphne E Lee

| Specimen number: OU 22650 | Age: 23 million years old (early Miocene, Waitakian stage) |

| Locality: Middlemarch, Otago | Rock Formation: Foulden Hills Diatomite |

| Collected by: DE Lee | |

| Citation: Lee DE, McDowall RM, Lindqvist JK. 2007. Galaxias fossils from Miocene lake deposits, Otago, New Zealand: the earliest records of the Southern Hemisphere family Galaxiidae (Teleostei). Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 37:109–130. doi.org/10.1080/03014220709510540 | |

A small, fleshy fin between the dorsal fin and the tail.

An ancient landmass that existed from the late Precambrian to the Jurassic, which upon fragmenting gave rise to Africa, Antarctica, Australia, India, Madagascar, South America, and Zealandia.

An animal that migrates between freshwater and seawater during different stages of their life cycle. Special cases include anadromous fish, which spend most of their life in freshwater but migrate to the sea, and catadromous fish, which migrate from the ocean to freshwater.

A former crater lake with abundant diatoms, and now a fossil site known for diatomite and famous for high-quality fossil preservation. Located near Middlemarch in Otago, New Zealand. See: Fossil Treasures of Foulden Maar.

Sedimentary rock composed of the frustules (shells) of diatoms, a type of algae.

Body structures like bones or shells are positioned as they would have been in life.

A sedimentary deposit that exhibits extraordinary fossil preservation, often including soft tissues.

An environment that lacks oxygen.

Disturbance of sedimentary deposits by living organisms.

A group of algae where many species in that group have a cell wall made of hydrated silicon dioxide (silica) which forms a shell called a frustule.

Any animal that is not a vertebrate (i.e. does not have a backbone). Examples include sponges, molluscs and echinoderms.

Fossilised faeces.