29 A feather star buried alive

Quite a few marine animals have been given fanciful common names that mostly belong to land plants. Some examples are sea anemones (cnidarians), sea-gooseberries (a kind of jellyfish), sea tulips (ascidians) and sea cucumbers (holothurians), not to mention moss animals (bryozoans) and sea lilies ( crinoids).

The crinoids fall into two groups – stalked crinoids which remain attached to the sea floor throughout life and feather stars which lose the post-larval stalk which attached them to the seafloor. They become free-living as adults, able to move across the seabed, or even, in some cases, to swim (there are videos on youtube).

The Geology Museum has many fossil specimens of isolated but distinctive round or star-shaped disarticulated plates of isocrinoid stalks, many from the Middle Triassic strata of the Murihiku Supergroup in Southland (Eagle 2003). Most specimens however, come from the mid-Cenozoic limestones and greensands of southern Zealandia.

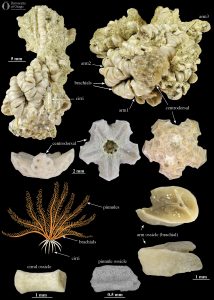

The skeletons of crinoids are composed of a range of small calcareous elements called ossicles, held together by ligaments and muscles, allowing crinoids to be very flexible. Within a few days of death, the skeletons disarticulate into individual ossicles. Large feather stars may have a skeleton of more than half a million ossicles! Once they have disarticulated there is only one ossicle that is distinctive enough to allow identification of the genus and species – the largest ossicle, the centrodorsal.

Crinoid limestones of Paleozoic age, containing a high percentage of crinoid ossicles, are fairly common in other parts of the world, as crinoids were extremely abundant in the distant past. Such limestones are much rarer in the Cenozoic. However, there is one site near Oamaru where the limestone comprises at least 30% crinoid ossicles (rather than the typical 1-2% seen at other nearby sites), the remains of what must have been a longstanding crinoid “meadow” on the seafloor.

Complete or semi-complete fossil feather stars are very rare, especially in the Cenozoic. So, the discovery of an almost complete feather star from Waipati in North Otago is of great importance. It seems likely that the animal was buried very rapidly, possibly while still alive. The specimen, collected by Ewan Fordyce in 1993 is catalogued as OU 44680. It was designated as the name-bearer for a new crinoid genus, Rautangaroa. Rau means feather in Te Reo and Tangaroa is the Maori word for sea.

A genus and species name had already been proposed for this species (in Eagle 2007), based on an isolated centrodorsal, but close examination of the new articulated specimen showed that it differed so markedly that a new genus name was required.

The other remarkable feature in this fossil is the presence of a regenerating arm. All echinoderms have the ability to regenerate body parts – think of starfish in rockpools with partly regrown arms.

This feature is also characteristic of living and fossil stalked crinoids but the Geology Museum specimen is the only known example of such regeneration in a fossil feather star.

– Written by Jeffrey H Robinson and Daphne E Lee

| Specimen number: OU 46680 | Age: Approximately 25 million years old (late Oligocene, Duntroonian stage) |

| Locality: Waipati, near Duntroon, North Otago | Rock Formation: Otekaike Limestone |

| Collected by: RE Fordyce | |

| Citation: Baumiller & Fordyce (2018). Rautangaroa, a new genus of feather star (Echinodermata, Crinoidea) from the Oligocene of New Zealand. Journal of Paleontology 92(5): 872-882. |