25 Transitional fossil at the dawn of baleen whales

Cetacea, Mysticeti: Tokarahia kauaeroa

Baleen whales are well adapted to life in water where they have evolved specialised feeding adaptations and behaviours. Living baleen whales lack teeth and use baleen to filter food from the water. Amongst living mysticetes, the rorquals are fast-moving predators, right whales are slower-moving grazers that skim the surface of the water to collect food, and gray whales collect their food from the sediment on the sea floor. The evolutionary timing of when ancient whales first developed these baleen-filtering feeding strategies is an important question in cetacean history. One group of ancient whales, the eomysticetids, has been especially important to finding the answer.

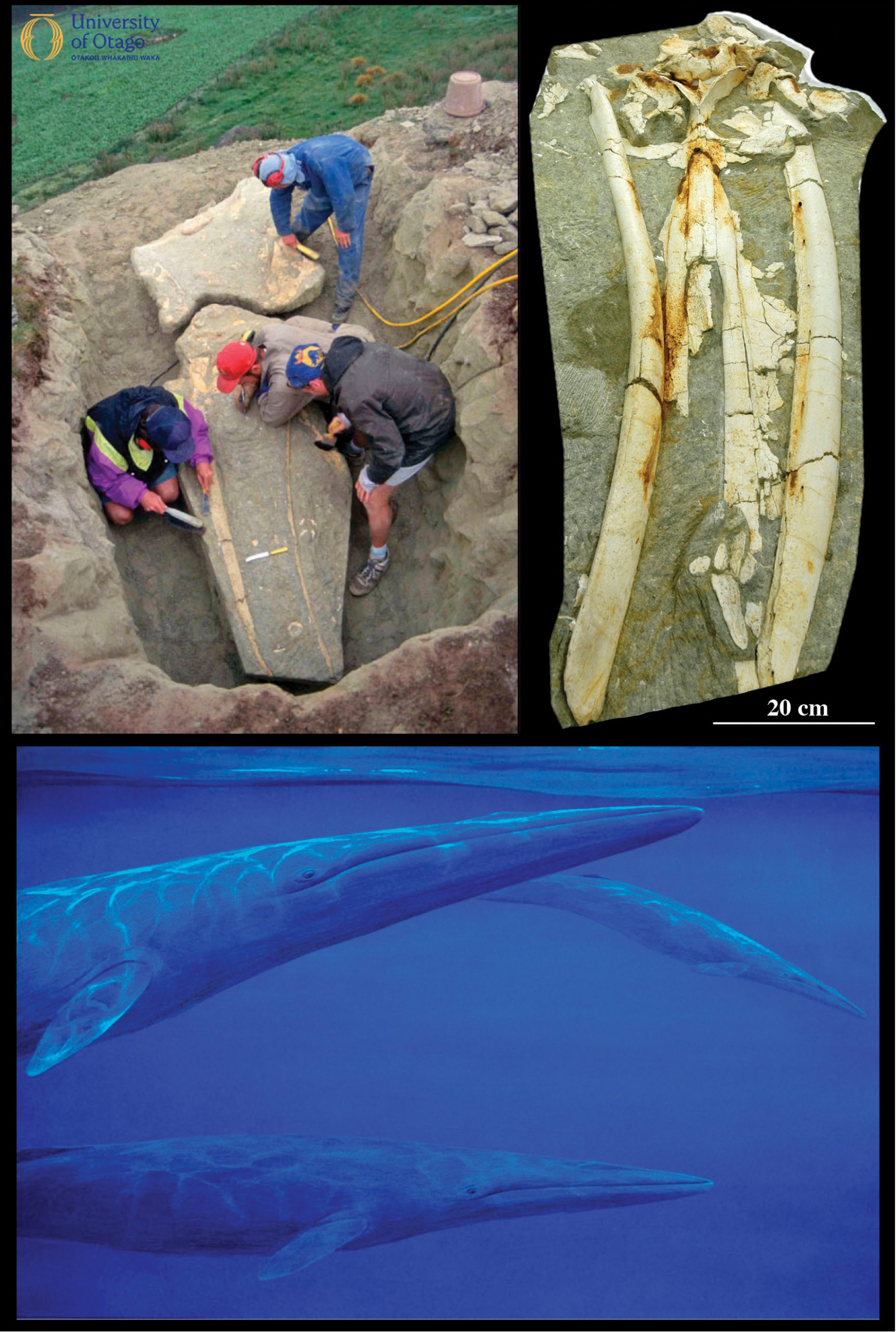

The top left image shows the bones of the fossil whale Tokarahia kauaeroa being collected from the North Otago location where it was discovered (specimen OU 22235). The top right image shows the bones of the upper skull and lower jaw after preparation to remove some of the surrounding sediment. The lower image is a reconstruction by artist Chris Gaskin showing what Tokarahia kauaeroa may have looked like while swimming in an ancient ocean. Image credits: RE Fordyce (photographs) and C Gaskin (Illustration). |

Eomysticetids are an extinct group of whales that occupy a branch in the evolutionary tree between early whales that all had teeth and more modern whales that have baleen. There exists an idea that eomysticetids may have had teeth as adults but not used them for feeding, relying instead on baleen. This idea is challenging to test because baleen is made from keratin and so is highly unlikely to preserve in the fossil record. Instead, researchers use the shape of the jaws of fossil whales to deduce if baleen might have been present when the animal was alive. From there, researchers can also check to see if teeth are preserved with these fossils. Ancient whales with this rare combination of traits (i.e. functional baleen and non-functional teeth) may have lived in the oceans surrounding Zealandia during the Oligocene.

In 1994 a large fossil skull was collected by Ewan Fordyce, Andrew Grebneff and others from the top of a limestone cliff in North Otago. The fossil was dated to between 25 and 26 million years old. The fossil shows a blowhole that is placed about halfway between the front-most end of the skull and the top of the head. The skull also shows a narrow upper jaw or rostrum. These are some of the features that identify the skull as being from an eomysticetid whale and which distinguish it from living modern baleen whales. This large skull would have belonged to an animal that was up to 7 metres long and, based on the shape of the skull, almost certainly had baleen when it was alive. In 2015, the fossil was described as Tokarahia kauaeroa by Robert (Bobby) Boessenecker and Ewan Fordyce and was formally determined to be part of the eomysticetid group of ancient whales. As part of this same study these researchers examined other, similar fossils. One of these closely related Tokarahia fossils was found as a fragmentary skeleton that included a single, isolated tooth.

The discovery of a tooth as part of this skeleton supports the idea that Tokarahia retained adult teeth. The peg-like shape and tiny size of the tooth, coupled with the shape of the skull of Tokarahia, suggested to the researchers that the tooth would have had no function in feeding. The delicate bones of the skull in Tokarahia further suggested it probably wasn’t a lunge feeder like living rorquals. Instead, Tokarahia may have used baleen for skim feeding or benthic suction feeding, with its teeth being just a vestigial feature of its jaws.

—Written by Daniel B Thomas

| Specimen number: OU 22235 | Age: Approximately 24.5 million years old (late Oligocene, Waitakian stage) |

| Locality: Tokarahi, North Otago | Rock Formation: Otekaike Limestone |

| Collected by: RE Fordyce, A Grebneff, CM Jones, BVN Black, CM Jenkins, G Curline | |

| Citation: Boessenecker RW, Fordyce RE. 2015. A new genus and species of eomysticetid (Cetacea: Mysticeti) and a reinterpretation of ‘Mauicetus’ lophocephalus Marples, 1956: transitional baleen whales from the upper Oligocene of New Zealand. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 175:607–660. doi:10.1111/zoj.12297 | |

Marine mammals within Cetacea that have large keratin plates (baleen) for filtering food from water. One of two major clades within Neoceti, with the other being Odontoceti. Living examples include blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) and southern right whale (Eubalaena australis).

Cartilage plates suspended from the upper jaw in the mouth of mysticete whales. Used to strain prey from sea water.

A family of cetaceans with nine living species including the blue whale Balaenoptera musculus.

A family of cetaceans with four living species including the southern right whale Eubalaena australis.

A family of cetaceans with a single living species, the gray whale Eschrichtius robustus.

A group of marine mammals with around 90 living species across two key clades, Mysticeti (baleen whales) and Odontoceti (toothed whales, including dolphins and porpoises). The fossils of many extinct species of cetacean have been discovered.

A protein that provides structural support to many epidermal tissues including hair and nails of mammals, feathers of birds, scales of reptiles.

Evidence of life from a past geological age. Remains like bones, shells or wood, or an impression like a footprint, or some other evidence of life, from something that was alive more than 11,700 years ago.

The mostly submerged continent of which New Zealand and New Caledonia are a part.

33.9 to 23.03 million years ago.

A sedimentary rock composed mainly of calcium carbonate. Can be formed from the skeletal fragments of marine organisms.

The region of a skull that holds the teeth, palate, and nasal cavity. Can be elongated into beak or bill.

A structure that has lost its original function through evolutionary time.