Part 1 – Teach

10 Neurodiversity-affirming teaching

Antonella Strambi

In a Nutshell

This chapter explores how a teaching approach that supports and affirms neurodiversity can be implemented. It highlights the importance of recognising and valuing neurodiversity, and provides practical strategies to create an inclusive learning environment. Key recommendations include offering varied methods of response, supporting executive functioning, facilitating physical action, and providing multiple means of engagement and representation. By adopting these principles, educators can enhance the educational experience for all students, including those who are Neurodivergent.

Why Does it Matter?

Supporting Neurodivergent students is crucial for their academic success and overall well-being. Without appropriate accommodations, these students may experience low self-esteem, social isolation, high anxiety, and burnout. These challenges can lead to poor academic performance and, in severe cases, dropping out of university and poor mental health. Moreover, Neurodivergent individuals often bring unique strengths such as creativity, attention to detail, and resilience, which enrich the learning environment. By fostering a Neurodiversity-affirming approach, educators not only help Neurodivergent students thrive but also promote equity and inclusion within the academic and broader community.

What does it look like in practice?

In this section:

- Neurodivergence and Neurodiversity: Definitions

- Why supporting neurodivergent students matters

- Strengths and Challenges of Neurodivergent Students

- Supporting and Affirming Neurodiversity with UDL

Neurodivergence and Neurodiversity: Definitions

Neurodivergence refers to ways in which some individuals think, learn, and interact with the world around them. The behaviours and experiences of these individuals are different compared to the majority of people referred to as Neurotypical. Therefore, neurodivergence has been traditionally viewed as a disorder or deficit that need to be diagnosed and managed through interventions and treatments. This perspective focuses on diversity as an impairment and seeks to ‘normalise’ neurodivergent people’s behaviour and cognitive functioning. For example, a student with ADHD might receive medication to help manage their symptoms so they can conform to conventional academic expectations. Common types of neurodivergence include Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Dyslexia, Dyspraxia, and Dyscalculia, among others.

In contrast with the medical approach to Neurodivergence, the social approach views neurological differences as natural and valuable variations of human cognition. The Neurodiversity paradigm recognises the strengths and unique contributions of Neurodivergent individuals, and attributes the challenges they may experience to social and environmental limitations (Lerner, Gurba, & Gassner, 2023). This perspective emphasises acceptance and empowerment rather than ‘curing’ or ‘fixing’ Neurodivergent individuals.

A Neurodiversity perspective encourages educators to remove or reduce environmental limitations by recognising the diverse needs of their students and adapting their teaching methods accordingly. For instance, instead of trying to make an Autistic student conform to typical social norms and physical classroom environments, a learning environment that supports Neurodiversity might provide choice in the ways all students experience sensory stimuli in the classroom, whether they want to work together or alone, and clear, structured instructions to facilitate learning. In other words, Neurodiversity promotes inclusive practices that support diverse ways of thinking and learning, and values diversity as an asset, by building on students’ individual strengths (Lerner, Gurba, & Gassner, 2023). Suggestions on inclusive practices are included later in this chapter.

Why supporting neurodivergent students matters

While the Neurodiversity paradigm holds promise when it comes to providing all students with ideals opportunities to learn, it must be recognised that there is work to be done in this area. This means that Neurodivergent students learning in the current Higher Education environments are likely to continue to experience challenges. As educators, it is important that we are aware of these potential challenges, so that we can best support our students.

Failing to adequately support Neurodivergent students can have significant negative consequences, both for the individuals affected and for the broader academic community. Without proper support, Neurodivergent students may experience a range of adverse outcomes that can impede their academic success and overall well-being. These may include:

- Low Self-Esteem. Neurodivergent students who do not receive appropriate accommodations and understanding may struggle with feelings of inadequacy and low self-esteem. When their unique needs are not met, these students might internalise their difficulties as personal failures rather than recognising these as caused by lack of support from the educational environment (Humphrey & Lewis, 2008). Low self-esteem can further impact students’ motivation and willingness to participate in academic activities.

- Feelings of Isolation. A lack of support can lead to feelings of isolation among Neurodivergent students. Social challenges and misunderstandings from peers can result in these students feeling excluded or marginalised within the university community (Cai & Richdale, 2016). This sense of isolation can hinder students’ ability to form meaningful connections and support networks, which are crucial for academic and personal development.

- High Anxiety and Burnout. The pressures of navigating an unsupportive educational environment can contribute to high levels of anxiety and stress for Neurodivergent students. Without appropriate accommodations, these students may find it difficult to manage their academic workload, leading to chronic stress and eventual burnout (Miller, Rees, & Pearson, 2021).

- Abandoning Studies. The combination of low self-esteem, isolation, anxiety, and burnout can lead some Neurodivergent students to abandon their studies altogether. A longitudinal study by Newman et al. (2011), for example, found that Autistic students were at a high risk of dropping out of post-secondary enrolment. This not only affects the individual’s educational and career prospects but also represents a loss of diverse perspectives and talents within the academic and broader community.

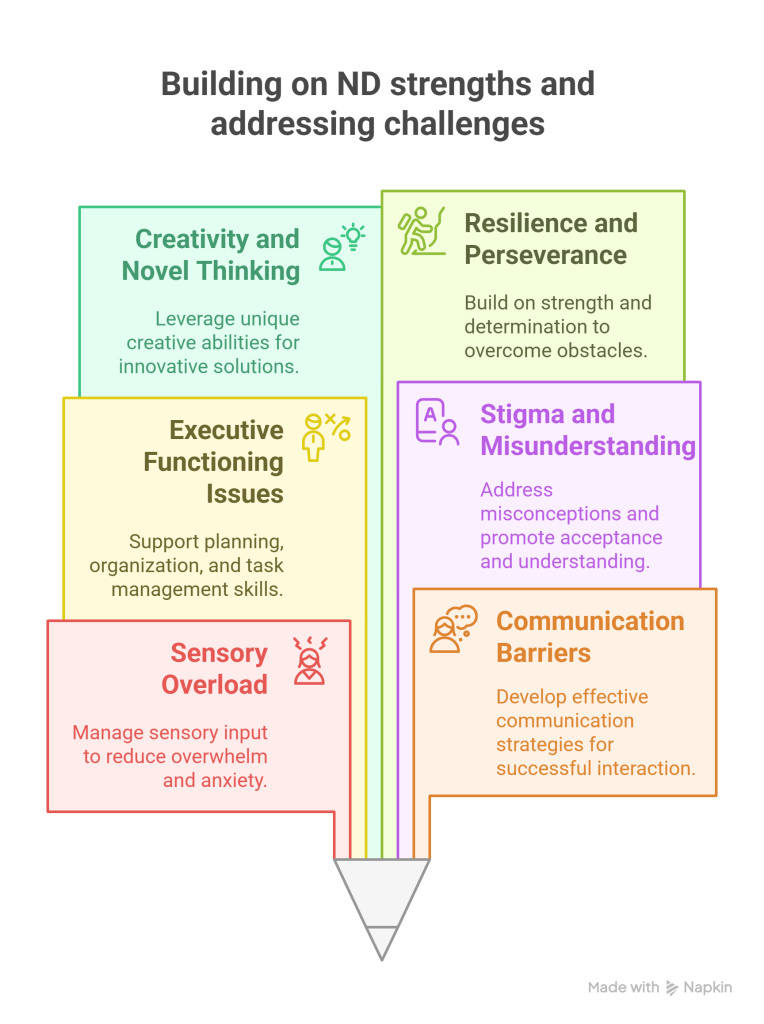

Strengths and Challenges of Neurodivergent Students

It is important to recognise that every student will experience neurodivergence differently; in other words, we cannot make assumption about a student’s challenges based on an existing diagnosis or identification with a type of neurodivergence (e.g. Autism or ADHD). However, knowing what challenges a student might be experiencing is a good starting point for a conversation with them, about what support they could benefit from. With this in mind, here are some challenges that are often experienced by Neurodivergent students:

- Sensory Overload. Many Neurodivergent individuals are highly sensitive to sensory stimuli. The typical university environment, with its bustling classrooms, bright lights, and constant noise, can be overwhelming. Sensory overload can lead to heightened anxiety, difficulty concentrating, and even physical discomfort (MacLennan, O’Brien, & Tavassoli, 2022).

- Communication Barriers. Neurodivergent students may experience difficulties with social interactions and communication. For instance, some Autistic students might struggle with understanding social cues, maintaining eye contact, and participating in group discussions. Students with ADHD may dominate conversations, go off on tangents, and interrupt other people. These behaviours – especially when misinterpreted by neurotypical students – can hinder Neurodivergent students’ ability to engage fully in classroom activities and form meaningful connections with peers and instructors (Cai & Richdale, 2016). Understanding what is expected of them, for example in assessments, may also be challenging for Neurodivergent students, unless clear and explicit instructions are provided.

- Executive Functioning Issues. Executive functioning skills, such as organisation, time management, and task completion, are often areas of difficulty for Neurodivergent students. Challenges in these areas can result in missed deadlines, procrastination and disorganised work, and increased stress (Barkley, 2022). Given that they are related to goal setting and achievement, these executive functioning challenges can significantly impact academic success.

- Stigma and Misunderstanding. Neurodivergent students frequently encounter stigma and a lack of understanding from their peers and educators. This can lead to feelings of isolation, low self-esteem, and reluctance to seek help (Butcher & Lane, 2023). Therefore, stigma and lack of understanding can adversely affect students’ mental health and academic performance.

Despite these challenges, Neurodivergent individuals often possess unique strengths that can greatly enhance the learning environment; these may include:

- Creativity and Novel Thinking. Many Neurodivergent students exhibit high levels of creativity and innovative thinking. Their ability to approach problems from different perspectives can lead to original solutions and insights. For example, individuals with Dyslexia have been found to excel in fields that require out-of-the-box thinking and problem-solving (Eide & Eide, 2011) as well as at visual-spatial reasoning (Armstrong, 2015)

- Attention to Detail and Deep Learning. Many Neurodivergent individuals, particularly those on the Autism spectrum, have an exceptional ability to focus on details and notice patterns that others might overlook. This attention to detail can be invaluable in disciplines such as mathematics, computer science, and academic research (Baron-Cohen et al., 2009). Hyperfocus is also frequently experienced by Neurodivergent students; this facilitates deep engagement with learning materials and the development of extensive knowledge in an area of interest.

- Resilience and Perseverance. The challenges faced by Neurodivergent students often foster resilience and perseverance. Their experiences of overcoming obstacles and finding strategies to cope with their differences can translate into strong problem-solving skills and a determined attitude towards achieving their goals (Gillespie-Lynch et al., 2017).

Although it may be useful to consider this information as a starting point, it is crucial to recognise that each student’s experience is unique. Open conversation is the only way of determining what strategies might work best for individual students. In addition to providing individualised support, we should also aim to design accessible and inclusive learning environments that support all students, regardless of their cognitive profile. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a useful framework for this purpose.

Supporting and Affirming Neurodiversity with UDL

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is an educational framework that aims to create inclusive learning environments by addressing the diverse needs of all students. By integrating UDL principles into teaching practices, we can create a supportive learning environment that enhances the educational experience not only for our Neurodivergent students, but for everyone. Importantly, rather than expecting Neurodivergent students to change to fit neurotypical expectations, UDL recognises that some of the challenges they experience can be resolved by removing environmental barriers.

Here are some suggestions, based on CAST UDL Guidelines [https://udlguidelines.cast.org/], that can be helpful to support neurodiversity in teaching:

Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression

- Allow Varied Methods of Response: Offer students different ways to demonstrate their understanding and knowledge, such as written assignments, oral presentations, or multimedia projects.

- Example: Enable students to submit a video presentation instead of a traditional essay.

- Support Executive Functioning: Help students develop organisational and planning skills by breaking tasks into manageable steps and providing tools such as checklists and planners.

- Example: Use project management software or templates to guide students through long-term assignments.

- Facilitate Physical Action: Ensure that classroom materials and activities are accessible to students with motor difficulties by providing options for physical engagement.

- Example: Use digital tools that allow students to interact with content using assistive technology.

- Example: Enable students to move around or bring fidget toys to release tension and improve focus.

Provide Multiple Means of Engagement

- Offer Choices and Autonomy: Increase student motivation by allowing them to make choices about how they learn and what topics they explore within the curriculum.

- Example: Let students choose between different project topics or select their preferred method of assessment.

- Foster Collaboration and Community: Create opportunities for peer interaction and collaborative learning to build a sense of community and support. Encourage all students to value diversity and teach team management skills. Consider allowing students to opt out of groupwork if it causes distress.

- Example: When working in teams, allow students to select team roles that match their strengths and preferences.

- Support Self-Regulation: Teach strategies for managing emotions and stress, and provide resources that help students monitor their progress and set achievable goals.

- Example: Incorporate mindfulness exercises and provide regular feedback on student performance that emphasises accomplishment and clearly identifies areas for improvement.

Provide Multiple Means of Representation

- Offer Information in Various Formats: Present content through multiple modalities such as text, audio, video, and visual aids. This allows Neurodivergent students to access information in ways that suit their learning preferences.

- Example: Use captioned videos, diagrams, and written summaries to explain complex concepts.

- Highlight Critical Features: Use visual and auditory cues to emphasise important information and guide students’ attention to key elements.

- Example: Highlight key terms in reading materials or use bold text and colour coding.

- Provide Alternatives for Perception: Ensure that information is accessible to students with sensory differences by offering alternatives for auditory and visual content.

- Example: Provide transcripts for audio recordings and descriptions for images.

If you are unable to provide flexibility in the means of representation and must make choices regarding visual elements, then these are generic accessibility guidelines1 that may be useful:

Fonts & Spacing

- Sans-serif fonts are best (e.g. Arial). Avoid fonts with short bars for p/b/d/q. Consider using Dyslexie or Open Dyslexic fonts

- Larger sizes are better – at least 12pt

- Good line spacing also helps – at least 1.2 (i.e. larger than single spacing)

Colours & Images

- Do not rely on colours only to convey information; green and red are especially difficult to distinguish for colour-blind people

- For reading, dark text over light background is best; good contrast can be helpful; however, avoid glare or too much contrast by using a lightly coloured background rather than white (for more details re. colour contrast and brightness, see Rello & Baeza-Yates, 2012).

- Avoid bright yellow as it can trigger sensory reactions; muted / pastel colours are preferred.

- Avoid using complex images as backgrounds – plain colours are best. If you have to superimpose text over an image, create a plain coloured box as text background.

- Using icons or photos can greatly help, as they convey core concepts visually and aid comprehension and memorisation. However, too many images can create clutter and be confusing, so reserve images for illustrating only the key concepts. Importantly, every image must have an ALT description so it can be processed by text-to-speech software.

Visual hierarchy

Neurodivergent students are likely to struggle separating core content from background information, especially if everything is presented in the same format.

- Highlighting core content can be achieved by breaking up text with appropriate headings and using position and size to create a visual hierarchy.

Knowledge Check – What Did You Learn?

To reinforce what you have learned through this chapter, you may wish to complete the following comprehension check questions.

What Does It All Mean for Me?

To make sense of the content and apply your learning to your context, try the following activity. This exercise is designed to help you reflect on and integrate the principles discussed in the chapter into your teaching practice.

Activity: Designing an Inclusive Lesson Plan

Review Your Current Lesson Plan:

- Select a lesson plan that you currently use or are planning to use.

- Identify areas where adjustments can be made to better support Neurodivergent students.

Apply UDL Principles:

- Integrate Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles into your lesson plan. Consider how you can provide multiple means of action and expression, engagement, and representation.

Specific Adjustments:

Multiple Means of Action and Expression:

- Include varied methods of response such as written assignments, oral presentations, or multimedia projects.

- Support executive functioning by breaking tasks into manageable steps and providing tools such as checklists and planners.

- Facilitate physical action by ensuring classroom materials and activities are accessible.

Multiple Means of Engagement:

- Offer choices and autonomy in learning activities and assessments.

- Foster collaboration and community while allowing opt-out options for group work if it causes distress.

- Support self-regulation by teaching strategies for managing emotions and stress, and providing regular feedback.

Multiple Means of Representation:

- Present content through various modalities such as text, audio, video, and visual aids.

- Highlight critical features using visual and auditory cues.

- Provide alternatives for perception by offering transcripts for audio recordings and descriptions for images.

Implementation and Reflection:

- Implement your revised lesson plan in a classroom setting.

- Reflect on the effectiveness of the changes. How did the adjustments impact student engagement and learning outcomes? What feedback did you receive from Neurodivergent students?

Continuous Improvement:

- Based on your reflections, identify further improvements. Consider conducting a survey or holding discussions with students to gather more insights.

References

Barkley, R. A. (2022). Executive functions: What they are, how they work, and why they evolved (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Baron-Cohen, S., Ashwin, E., Ashwin, C., Tavassoli, T., & Chakrabarti, B. (2009). Talent in autism: Hyper-systemizing, hyper-attention to detail and sensory hypersensitivity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1522), 1377-1383. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2008.0337

Butcher, L., & Lane, S. (2023). Neurodivergent (Autism and ADHD) student experiences of access and inclusion in higher education: An ecological systems theory perspective. Journal of Neurodiversity in Higher Education, 5(2), 123-145.

Cai, R. Y., & Richdale, A. L. (2016). Educational experiences and needs of higher education students with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(1), 31-41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2535-1

Eide, B., & Eide, F. (2011). The dyslexic advantage: Unlocking the hidden potential of the dyslexic brain. Penguin Group USA.

Gillespie-Lynch, K., Brooks, P. J., Someki, F., Obeid, R., Shane-Simpson, C., Kapp, S. K., Daou, N., & Smith, D. S. (2017). Changing college students’ conceptions of autism: An online training to increase knowledge and decrease stigma. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(8), 2329-2346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2468-0

Humphrey, N., & Lewis, S. (2008). `Make me normal’: The views and experiences of pupils on the autistic spectrum in mainstream secondary schools. Autism, 12(1), 23-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361307085267

Kinnear, S. H., Linker, J., & Langley-Turnbaugh, S. J. (2016). Understanding the experience of sensory overload from the perspective of adults with autism. Occupational Therapy International, 23(4), 401-410. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.1431

Lerner, M. D., Gurba, A. N., & Gassner, D. L. (2023). A framework for neurodiversity-affirming interventions for autistic individuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 91(9), 503–504. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000839

MacLennan, K., O’Brien, S. & Tavassoli, T. (2022) In Our Own Words: The Complex Sensory Experiences of Autistic Adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52, 3061–3075. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05186-3

Miller, D., Rees, J., & Pearson, A. (2021). “Masking is life”: Experiences of masking in autistic and nonautistic adults. Autism in Adulthood, 3(4), 330–338. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0083

Newman, L., Wagner, M., Cameto, R., Knokey, A. M., & Shaver, D. (2011). The post-high school outcomes of young adults with disabilities up to 8 years after high school: A report from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2). National Center for Special Education Research.

Rello, L., & Baeza-Yates, R. (2012) Optimal Colors to Improve Readability for People with Dyslexia. Text Customization for Readability Online Symposium, W3C. https://www.w3.org/WAI/RD/2012/text-customization/r11

Additional Resources

If you would like more guidance on making your teaching more inclusive and accessible, you might find these resources useful:

- ADCET – The Australian Disability Clearinghouse on Education and Training offers numerous resources, including recorded webinars, to support access and inclusion; some of these resources are specific to Neurodiversity.

- CAST offers a comprehensive introduction to UDL as well as the UDL Guidelines.

- This book focuses on creative inclusive environments for tertiary learning: Cardon, L. S., & Womack, A.-M. (2023). Inclusive college classrooms: teaching methods for diverse learners. Routledge.

Media Attributions

- Neurodivergent students | Strength and Challenges – visual selection © Generated using Napkin.ai is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license