Part 2 – Design

27 Writing Effective Online Quiz Questions

Antonella Strambi; Joshua Cramp; Richard McInnes; and Kirsty Summers

In a Nutshell

In this chapter, we explore ways we can take advantage of the convenience offered by online quizzes, while at the same time maintaining rigour in the assessment of our students’ learning. Firstly, we discuss validity and how to ensure that we are indeed assessing what we should. We then suggest strategies for writing effective multiple-choice questions (MCQs) and present suggestions for presenting quiz questions online to ensure that cognitive load is minimised and validity is upheld.

Why Does It Matter?

Online quizzes can be an efficient tool for assessing your students’ learning. Writing effective questions, however, is a learned art that requires thoughtful consideration of several factors.

Two main concerns when it comes to writing effective quiz questions are validity and cognitive load (Parkes & Zimmaro, 2016; see also the Assessment Design chapter). A quiz and each individual question are valid when they measure what they aim to measure and not some other extraneous variable. Cognitive load is related to validity: if students have to spend too much time and effort understanding how the quiz is organised, and what they are being asked to do, then this limits their ability to demonstrate their knowledge and understanding of concepts, which is what we really want to assess.

What Does It Look Like in Practice?

In this Section:

- What are we Assessing?

- Writing Effective MCQs

- Presenting Quiz Questions Online

What are we Assessing?

The first step in quiz writing is to identify the learning outcomes that will be assessed. Start by revisiting your course objectives or learning outcomes, and look at the verbs through which they are expressed: are students expected to describe, apply, analyse, or evaluate? These verbs indicate different levels of ‘knowledge’ and should guide you in writing your questions. More information about course learning outcomes and their importance is included in the Constructive Alignment for Course Design chapter.

There are several taxonomies of learning that show levels of knowledge and the types of actions that are typically associated with them. Among the most popular cognitive learning taxonomies are Bloom’s (1956), Krathwohl’s (2002), and Bigg’s SOLO. Table 1 provides examples of action verbs that can be used to assess learning at each level of the three taxonomies. You may like to search the table by action verb to narrow the amount of information that you are reading at a time.

Table 1: Levels of ‘knowledge’, question examples and types

It is important to note that every subsequent level in a learning taxonomy implies all preceding ones. For example, to be able to synthesise, students must be able to apply; to be able to apply, they must be able to comprehend, and so forth. Therefore, there is no need to test lower levels, if they are implied in performance at higher levels. This minimises the risk of over-assessing and creating excessive cognitive load.

One way of shifting a question toward higher-order thinking is to ask ‘why’ or ‘how’ questions, rather than ‘what’. Using scenarios, vignettes, graphs, tables or graphics as contexts for sets of questions can be very effective; for example, a case study can be followed by MCQs that require students to infer, interpret, apply, analyse, synthesise, etc. Alternatively, a set of closed questions could be followed by one open question that asks students to explain or justify their answers.

Online quizzes are especially suited for this type of input, as scenarios can be presented using multimedia or software applications that recreate the authenticity of professional settings (Cramp et al. 2019). If you write questions that involve higher-order thinking, however, keep in mind that students will need more time to form a response, compared to quizzes that involve simple recall or application.

Writing Effective MCQs

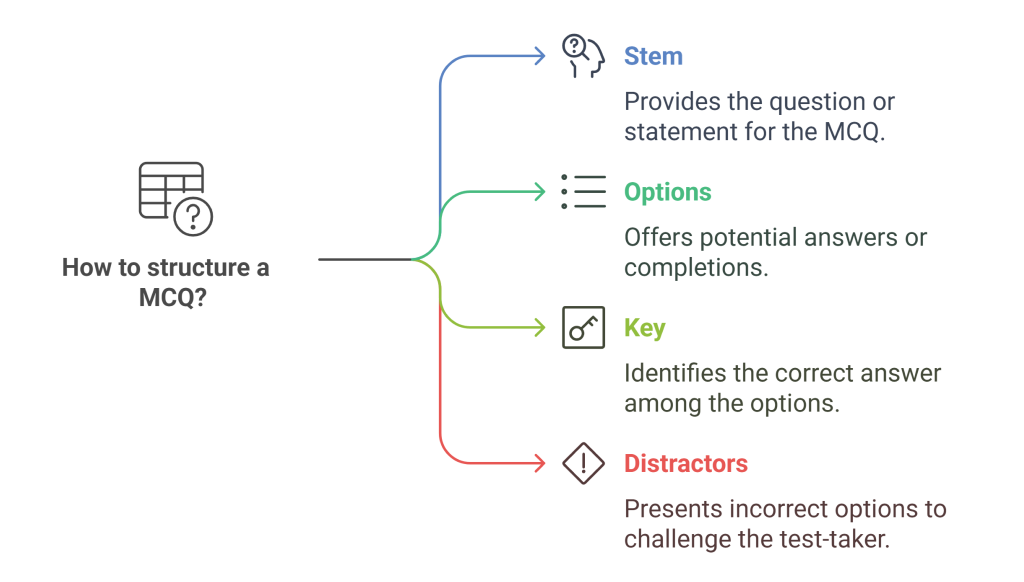

MCQs tend to be among the most popular format of quiz questions. They offer the convenience of automated marking, but as we have observed, they can be written to assess higher-order thinking. Therefore, MCQs can be an effective and efficient way of assessing learning outcomes. MCQs have a two-part structure:

- A stem, which can be a question or a statement and

- A set of options that answer or complete the stem. One of these options is the key, or the correct option; the other options are called distractors.

Writing effective MCQs can be challenging. There are many resources that list the do’s and don’ts of MCQ writing, some of which are listed in this guide. The two principles of assessment introduced at the outset of this chapter, i.e. validity and cognitive load, provide a helpful framework for MCQ writing. Other important considerations, as discussed in Jay Parks and Dawn Zimmaro’s book, Learning and Assessing with Multiple-Choice Questions in College Classrooms, include:

- Language should be only as verbose and/or complex as it needs to be. If a learning objective is that students will be able to discriminate between relevant and irrelevant information, then having information that students must ‘weed out’ would be a valid choice. Similarly, if students must be able to use professional terms, then having these terms in the question would support assessment validity. What we want to avoid, however, is if students are unable to demonstrate their knowledge because of the way the question was worded. For example, they didn’t understand the language used in the question, or the question was so long that they got lost in it. As a rule of thumb, the stem should only include information that students need in order to select the correct option.

- Avoid negative statements if possible as they are cognitively more demanding than positive statements and can affect validity. If a student selects an incorrect answer it could very well be because they didn’t notice the negative form. If negatives must be used, then students’ attention should be drawn to them (e.g. using bold typeface or adding a warning).

- The key must be ‘unambiguously correct’ and ‘represent some consensus of the field’ (Parkes & Zimmaro, 2016, p. 26). We must be able to offer evidence (e.g. from the textbook or relevant resources from our discipline) that it is indeed correct, and not just what we think is correct. However, it is possible to have keys that are the best option rather than the only one that’s correct. In the best opti`on approach, the distractors may not be completely incorrect, but they are not as effective as the best option. If this approach is used, students should be made aware of it.

- Direct questions are best in terms of minimizing cognitive load and are therefore preferred. Incomplete statements are acceptable, but they work best when the gap is at the end of the sentence rather than in the middle, as the gap in the middle is cognitively more demanding. If, however, having the gap at the end of the stem causes a lot of repetition in the options, then it’s best to have a gap in the middle and eliminate the repetition.

- The number of options should be between 3 and 5. If we want MCQs to be valid, the distractors must be plausible, i.e. students who haven’t studied the material properly must think a distractor could indeed be correct. If we cannot find more than two plausible distractors, it’s best to keep to 3 options (one key, two distractors) rather than creating an extra distractor that no sensible test-taker would think of as correct.

- Avoid using ‘all of the above’ or ‘none of the above’. These options introduce threats to validity in different ways; they make it easier for students to guess the correct answer and do not truly test learning objectives.

- Avoid other forms of ‘cueing’, e.g. sentence length, sequencing, or category of options. The key often contains more detail and therefore tends to be longer. If students identify this as a pattern, they will be able to guess the correct answers without necessarily knowing the content. Similarly, quiz writers tend to avoid placing the key as first or last option. Finally, if one of the distractors is in a different category group (e.g. a feline where all other options are canines), then this is a clear cue that there is something special about it.

You can find annotated examples of well and poorly written MCQs, as well as examples of how MCQs can be used to assess higher-order thinking, in the following resources:

- Resource – Melbourne CHSE Guide on Multiple-Choice Questions

- Article – Scully D 2017, Constructing Multiple-Choice Items to Measure Higher-Order Thinking, Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, vol. 22, no. 4.

- Resource – Wiley Writing Quiz Questions

Presenting Quiz Questions Online

Once you have decided on the content and form of your quiz questions, the next step is thinking about how questions are going to be organised and displayed on the screen. Students interact with online quizzes in a fundamentally different way to paper-based ones (Macedo-Rouet et al. 2009), which must be considered to ensure that cognitive load is minimised and validity is upheld. Our goal is to eliminate extraneous content, logically and aesthetically format content, and focus student’s attention with visual signals (Gillmor, Poggio, & Embretson 2015). But what do these strategies look like in practice? Let’s consider a couple of common examples.

In quizzes that contain sets of questions relating to a scenario or that require students to access a formula sheet or similar information source, consider providing this information in advance so that students can download it before the quiz opens or at the start of the quiz. This way, students can have documents side-by-side on the computer screen or have a printout. This reduces the volume of information that needs to be in their working memory, thus increasing their capacity to process the question/answer.

When drafting a question that involves a significant amount of context, also consider visually separating out the context from the question, such that the question is more obvious (i.e. stands out) to students. If the question asks students to demonstrate more than one thing (e.g. list two factors, describe their importance and provide your underlying rationale) consider structuring this is a list rather than a sentence, such that the deliverables can be gleaned at a glance.

If your quiz contains a collection of related questions in a multi-part set, all questions should be visible on the screen together. This enables students to see their mutual connections and enables you to make explicit links between questions. On the other hand, when questions are not related to one another, displaying one question at a time helps students focus without distractions.

Be sure to communicate to students the marking allocation for sub questions and alter the size of the text field (for essay questions) to guide the length and coverage of their response. In addition, ensure that you don’t over rely on text formatting to draw student attention. Use one option only e.g. bold and use it consistently across all questions.

At UniSA…

If you are a UniSA staff member, you may find the following resources useful:

Knowledge Check – What Did You Learn?

Here are a few questions to help you check your understanding of the concepts discussed in this chapter:

What does it all mean for me?

Now it is time for you to explore and apply principles for designing effective Multiple-Choice Questions (MCQs) that assess higher-order thinking skills. For this activity we would like you to:

reflect on the principles discussed in this guide and how they apply to your course(s)

- choose a relevant learning objective from one subject/course,

- design a sample MCQ(s) that assess higher-order thinking skills

How

- Identify a learning objective from your subject area that you believe could be effectively assessed through MCQs

- Consider how the objective aligns with the taxonomies of learning listed in table 1.

- Review the suggestions for types of questions for those taxonomies. Consider whether you are you able to create a MCQ using those examples as a guide.

- Create a MCQ with a stem, 2 distractors and a correct answer.

- Review your MCQ against the criteria outlined in the ‘Writing Effective Questions’ section

- Reflect on:

- Whether your MCQ assesses the learning objective effectively

- Whether it assesses higher order thinking skills

- Is direct, with no extraneous information contributing to increased cognitive load

References

Bloom, B. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The Ccassification of educational goals. Handbook 1, Cognitive Domain. Longman.

Chiavaroli, N. (2017). Negatively-worded multiple choice questions: An avoidable threat to validity. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 22(3), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.7275/ca7y-mm27.

Cramp, J., Medlin, J. F., Lake, P., & Sharp, C. (2019), Lessons learned from implementing remotely invigilated online exams, Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 16(1), 1-20.

Gillmor, S., Poggio, J., & Embretson, S. (2015). Effects of reducing the cognitive load of mathematics test items on student performance. Numeracy, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.5038/1936-4660.8.1.4.

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 212–218.

Macedo-Rouet, M., Ney, M., Charles, S., & Lallich-Boidin, G. (2009). Students’ performance and satisfaction with Web vs. paper-based practice quizzes and lecture notes. Computers & Education, 53(2), 375–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.02.013.

Morrison, S., & Walsh Free, K. (2001). Writing multiple-choice test items that promote and measure critical thinking. Journal of Nursing Education, 40(1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.3928/0148-4834-20010101-06

Parkes, J., & Zimmaro, D. (2016). Learning and assessing with multiple-choice questions in college classrooms, Routledge.

Scully, D. (2017). Constructing multiple-choice items to measure higher-order thinking, Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 22(4), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.7275/swgt-rj52.

Media Attributions

- How to structure a MCQ? © Generated with Napkin.ai is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Private: UniSA Logo