Part 2 – Design

25 Assessment Design for Academic Integrity

Amanda Janssen

In a Nutshell

This chapter considers what academic integrity means and why it is important. We then look at the converse – academic misconduct — and what we believe constitutes misconduct, in what circumstances it is likely to happen, and what we can do to minimise risk of this occurring through assessment design.

Why does it matter?

Assessment design plays a crucial role in promoting academic integrity. By understanding the relationship between assessment practices and the likelihood of academic misconduct, we can create assessments that minimise opportunities for dishonest behaviour. This not only helps maintain the integrity of the institution but also supports students in developing honest academic behaviours and achieving authentic learning outcomes. Thoughtful assessment design ultimately protects the value of educational achievements and fosters a culture of honesty and responsibility within the academic community.

What does it look like in practice?

In this section:

- What is Academic Integrity?

- What is Academic Misconduct?

- A multi-layered approach for mitigating misconduct

- Assessment Design and Academic Integrity

What is Academic Integrity?

Academic integrity is the foundation of every aspect of our university life. Each institution may have its own definition of Academic Integrity. In Australia, there is also a sector-wide definition offered by TEQSA:

‘the expectation that teachers, students, researchers and all members of the academic community act with: honesty, trust, fairness, respect and responsibility.’

While the TEQSA definition may give the impression that academic integrity is an easy to explain concept, Bretag (2016) points out that “Academic integrity is such a multifarious topic that authors around the globe report differing historical developments which have led to a variety of interpretations of it as a concept and a broad range of approaches to promulgating it in their own environments” (p. 3). This quote is from an edited book, titled Handbook on Academic Integrity which, among other things, locates academic integrity in an international and historical context. The book illustrates the diverse international themes and views on academic integrity and makes for a very interesting read.

We have asked three UniSA’s Academic Integrity Officers to define Academic Integrity in their own words. Watch this video to hear their responses: <consent forms obtained from two of the three interviewees>

A transcript of the conversation recorded in this video is also available.

What is academic misconduct?

Academic misconduct occurs when students or staff fail to uphold integrity in their academic work. Simply put, academic misconduct represents a breach of academic integrity principles and expectations. The term “academic dishonesty” is often used interchangeably with academic misconduct.

Academic misconduct manifests in different forms, varying in complexity and severity. The higher education institution Academic Integrity Policies identify different behaviours that undermine academic integrity (TEQSA, 2022)

Plagiarism:

- Directly copying material from electronic or print sources without proper acknowledgment

- Closely paraphrasing sentences or passages without citing the original work

- Submitting another student’s work, either in whole or in part

- Using another person’s ideas, work, or research data without acknowledgment

- Appropriating or imitating another’s ideas

Other Forms of Academic Misconduct:

- Breaching examination procedures in ways that breach academic integrity

- Presenting or submitting copied, falsified, or improperly obtained documents or data

- Submitting academic work produced through generative artificial intelligence tools

- Collusion: Unauthorized collaboration in preparing or presenting work, including knowingly allowing others to copy personal work

- Contract cheating: Outsourcing assessments to third parties, whether commercial providers or non-commercial sources such as current or former students, family members, or acquaintances

- File sharing: Exchanging exam questions or assignments with other students, or uploading assignments or exam questions to online file-sharing or study sites

- Providing significant assistance to students in completing or presenting their academic work

- Fabricating or falsifying information or student identity

- Offering or accepting bribes for academic advantage

Important Legal Note: In Australia, providing or advertising academic cheating services related to higher education delivery is a criminal offence.

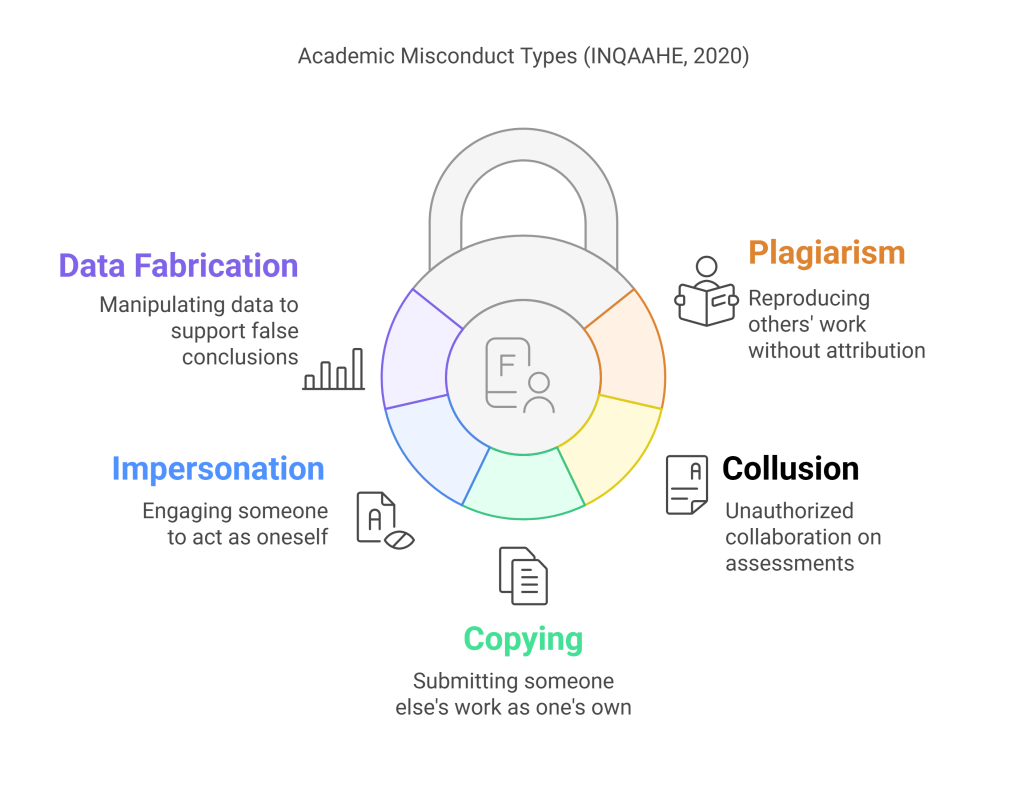

The International Network for Quality Assurance Agencies in Higher Education (INQAAHE) categorises and defines the different types of academic misconduct as follows:

- Plagiarism involves the reproduction of another’s work without attribution.

- Collusion is where a number of individuals work together to complete an assessment but are not authorised to do so.

- Copying is where an individual reproduces and submits work completed by someone else, with or without their permission. The person whose work is copied may also be culpable if they have not taken steps to ensure their work is safe from being reproduced by others.

- Impersonation involves engaging another to act as oneself or presenting oneself as another (usually in an in-person examination). Contract cheating is where an individual outsources an assessment.

- Data fabrication or falsification involves supporting false conclusions through the manipulation or invention of data and/or images (INQAAHE, 2020, p. 6).

A multi-layered approach for mitigating misconduct

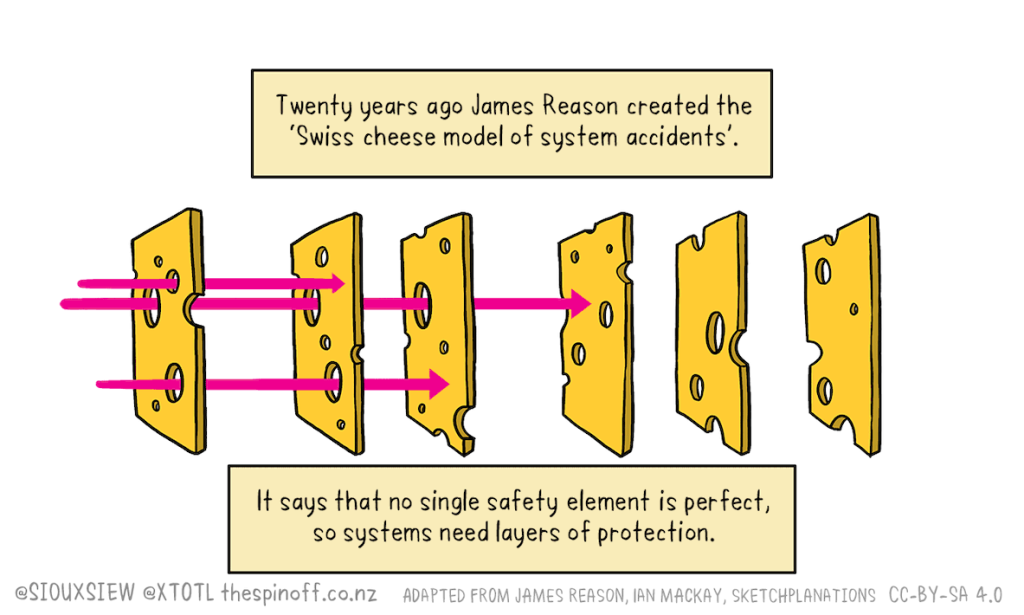

Mitigating Academic Misconduct requires a multi-layered, university wide approach. James Reason (1990) proposed a Swiss Cheese model, where each initiative is represented by a slice of cheese which acts as a barrier against academic misconduct, and the holes in the cheese slice represent weaknesses in the system. However, when the slices are layered together, they act as a stronger defence. Kiata Rundle then applied this work to academic integrity, where they demonstrate how preventing misconduct requires rather than a single intervention, to have ‘multiple semi-permeable barriers’ (p.102) looking at the cultural contexts that shape behaviour, the systems for prevention and detection, student education, and enforcement mechanisms.

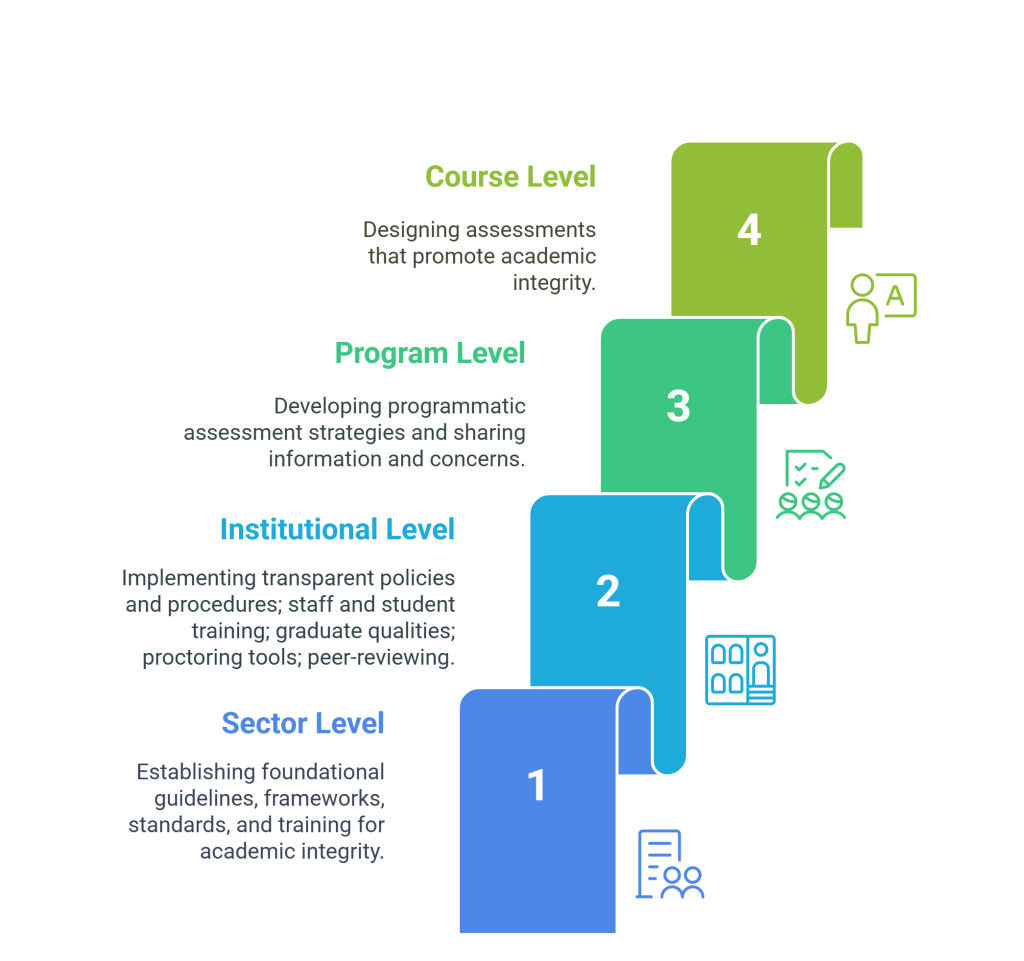

From a higher education perspective, we can consider a broader approach by looking at how we can apply this model across the sector. Of course, the fewer the ‘holes’, the better. Therefore, it is important to look for potential issues at each level and try and mitigate them. When applied to the Academic Integrity context in the Tertiary Education sector, the Swiss cheese model comprises many layers that protect us from academic misconduct; these include initiatives at the sector, institutional, program, and course levels. In other words, upholding Academic Integrity is everybody’s responsibility.

Assessment Design and Academic Integrity

In this section, we focus on the course design level of the ‘Swiss cheese’ model, and specifically on assessment design. All assessments are open to academic misconduct, as shown in the Australian Education Report 2018. However, some assessments are more susceptible to misconduct than others. Understanding the relationship between assessment design and academic integrity is useful in helping us avoid potential pitfalls and ensuring that the risk of misconduct is minimised.

There are at least two ways to think about this topic. One way is to consider the types of assessment where there is a higher likelihood of misconduct. By types we refer to the method and/or format by which a student is assessed, for example, an essay, an invigilated examination, an online quiz, a presentation, etc. (Struyven et al.,2005)1. Another way is to consider the assessment practices of academics which may cut across different assessment types. This could include assessment task scheduling, weighting, volume, feedback practices, nature of instructions and other decisions related to the administration of the assessment.

A study undertaken in 2015 surveyed 14, 000 students to get their view on which assessments were more likely to encourage students to ‘cheat’ (Bretag, et al., 2019). The study also surveyed over 1,100 staff on the assignments they were likely to use. The results of this study show the assessments that students think are more susceptible to cheating as well as the assessments that staff are likely to use. From the students’ perspective, all assessment tasks considered in the study have a likelihood of being subjected to academic misconduct, but to varying extents. A higher percentage of students think that certain assessment practices make it more likely for students to cheat than others, these include:

- Tasks that have a short turn-around time

- Heavily weighted tasks

- Series of small-graded tasks

- Tasks involving research, analysis and thinking and,

- Those requiring integration of knowledge

Students who tend to cheat see more opportunity to cheat across different assessment practices/approaches than those who don’t cheat.

Some of these practices or types of assessment where likelihood is high are also highly used by academics in assessing students, particularly research, analysis and thinking, and knowledge integration. This potentially increases the rate of academic misconduct.

As you may notice, it would seem it is more how students are asked to do assignments, and/or the circumstances/context of the assessment than what they are asked to do that increases the likelihood of cheating.

There are other practices or circumstances which may contribute to likelihood of misconduct. These include:

- Assessment that does not align to intended learning outcomes, making the task inauthentic.

- Repeating the same questions every year unless they are individualised, context specific and/or application based.

- Lack of practice in, or exposure to, similar tasks before doing the actual assessment.

- Related to the above point, lack of support to students while they prepare and carry out the assessment task (i.e. limited or no learner scaffolding).

Based on the above discussion we can conclude that any assessment practice that does not give students time on task or opportunities for practice, has little or no feedback on performance tasks, lacks authenticity, is unclear in its expectations or creates excessive pressure is likely to increase the chances of academic misconduct. These are the same principles that are discussed in the Principles of Assessment Design chapter.

Thus, strategies that address these deficiencies are necessary in assessment design to enhance academic integrity among students. Of course, as evident from Bretag et al.’s (2019) study, students with a tendency to cheat will always find opportunities to cheat even if these are addressed. In this case, different strategies are needed beside assessment design, and this is beyond the scope of this chapter.

A scoping review, by Egan (2018), investigated how assessment design can be used to promote academic integrity and reached similar conclusions to those outlined above. Egan recommends that assessment:

- scaffolds students through the development of academically honest behaviours.

- allows students to incorporate some of their own personal experience, ideas, or reflections.

- moves from no-grade to low-stakes to high-stakes to support students as they develop their confidence over time.

- uses a personalised approach. These assessments can be small and sequential, with prompt feedback.

- is embedded into coursework, rather than a stand-alone ‘academic integrity-type’ module.

- provides feedback on the specific skills to be developed to students in a productive and timely way.

- provided examples of ‘good’ responses to ensure that all students have the same understanding of academic integrity.

This list of recommendations is only one of several lists that can be found in the literature. A popular framework designed to support academics’ decisions about their assessment practices was developed by Bearman et al., 2016 and reinforced as a valid way to support academic integrity by Philip Dawson (2021).

The framework guides academics in making decisions that take into account competing demands and considerations. It identifies 6 important factors that affect assessment design:

- purposes of the assessment

- context of the assessment

- feedback processes that are in place

- types and ranges of assessment tasks

- learner outcomes

- interactions. This includes the interactions between learners and the assessment, and the information and support needed for improving the assessment in subsequent offerings.

A detailed guide discussing each of 6 factors is available from the Assessment Decision project website.

It is important to note that we may not have the same level of control over all the categories of factors. Generally, the purpose (at least in a general sense), the context and the learning outcomes are predetermined at the curriculum design and approval stage. On the other hand, as educators may have more leeway around Tasks, Feedback Processes, and Interactions.

Assessment Decisions & Academic Integrity

By applying the Assessment Decision framework to the design of assessment that supports academic integrity, we offer the following suggestions:

Purpose

- Ensure that every assessment has a clear and bold rationale that is shared with students, so that the task is viewed as meaningful and relevant to students’ learning. This fosters meaningful engagement and minimises risks of misconduct.

Context

- Know your learners’ characteristics and associated learning needs. Explore supporting and scaffolding mechanisms to address any needs that may dispose students to wanting to engage in academic misconduct (e.g., see Egan (2018)’s recommendation no. 3).

- Consider the assessment regime across the course and program, and ensure, as much as possible, that there is an explicit continuity and connectedness across the individual tasks.

- Consider the mode of learning and what academic integrity opportunities and risks it brings with it. Design assessment in ways that maximises opportunities and minimises the risks e.g., leveraging on the LMS quiz settings to prevent academic misconduct or considering alternate assessment to an examination for online students.

Learning Outcomes

- Clearly demonstrate to students the constructive alignment between assessment, and learning outcomes and learning activities and resources

- Consider all valid ways in which the learning outcomes can be assessed and select the assessment method or approach with the least likelihood of academic misconduct.

Tasks

- Have clear instructions on what the students are required to do, and how.

- Explain to students the rationale for the assessment and the assessment approach.

- Where applicable, break the assessment into its constituent parts or stages.

- Schedule assessment tasks in a manner that allows students enough time to understand their required content, prepare, ask for feedback, and finalise their submission (too much pressure may lead to a temptation to engage in academic misconduct); this includes consideration around how the different tasks are distributed across the study period relative to others, as well as to relevant topics.

- For high stakes or heavily weighted tasks, ensure they are challenging and require students to do one or more of the following: application, integration of different skills or understandings, problem solving, reflection, creativity or personalisation or contextualisation.

- Ensure responses to your assessment questions are not searchable online.

- Emphasise on process, not just product of assessment – this provides opportunities for feedback and self-regulated learning and ownership throughout the period of engaging with the task.

- Discuss and/or clarify assessment criteria and demonstrate expected standards.

- Ensure that students cannot use work from previous cohorts.

Feedback Processes

- Provide opportunities for constructive/developmental formative feedback including feedback that targets academic integrity issues.

- Encourage student-teacher dialogue about assessment.

- Ensure summative feedback is part of the learning processes and preparation for the next assessment.

- Devise timely feedback mechanisms to avoid student frustration. Be realistic (and honest) about constraints and ensure feedback is received before the next task is due.

Interactions

- Explain assessment tasks clearly to students and communicate how students can be successful while maintaining academic integrity. This includes explaining what academic misconduct might look like in a particular assessment.

- Provide students with resources that help them understand how to adhere to expected standards or disciplinary norms (e.g., referencing, or acceptable formats/structures).

- Provide clear information about where students can go for support if they are struggling, including academic support services (e.g. writing centres) and counselling (e.g. to address time management, anxiety, and procrastination).

- Explain the ramifications of academic misconduct, both immediate and long term.

At UniSA…

Academic Integrity is defined in the Academic Integrity Policy (AB 69) and the Academic Integrity Procedure (AB 69-P1). Please read page 2 and 3 of the Policy to remind yourself of the definition.

Knowledge check

Which assessment types do you think are associated with the different types of academic misconduct? This activity encourages you to reflect on your own beliefs about assessment design and academic integrity. Drag and drop different assessment types (shown as grey rectangles) into the most appropriate form of academic misconduct according to how likely you think they might occur in that category. Each assessment type can fit into more than one category. Note that there is no right or wrong answer – you may want to access some of the scholarly literature on this subject to check whether your understanding is supported by the available data. You may also want to compare your classification to one of your colleagues’, as a starting point for a conversation to establish shared understanding.

What does it all mean to me?

- Find any policies and procedures documents at your own institution. UniSA staff can access the local Academic Integrity Policy and Academic Integrity Procedure.

- Use the following questions to guide your reflection:

- In your view, why is academic integrity important?

- How would you define academic integrity in your courses?

- How does your own definition differ (if at all) from the definitions we have provided in this chapter?

- Is your institution’s current definition of academic integrity enough – should there be more or less? Why?

- Review the information in this chapter on practices that may make assessment more susceptible to academic misconduct. Examine past cases of academic misconduct in your teaching context against this information. Could there be a relationship between these cases and choices in assessment types and practices?

Additional Resources

- Epigeum Learning Module. This module designed by Oxford University Press in collaboration with a number of academic experts. It contains many activities and resources that will demonstrate how academic integrity works in practice.

- TEQSA Masterclass – a short course and accompanying situational judgement test (SJT) to build your baseline knowledge about academic integrity issues and techniques and practices for deterring and detecting contract cheating.

References

Bretag, T. (2016). Educational integrity in Australia. In T. Bretag (Ed.) Handbook of academic integrity (pp. 23-38). Singapore: Springer.

Bretag, T. et al. (2019). Contract cheating and assessment design: exploring the relationship. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(5), pp. 676-691.

International Network for Quality Assurance Agencies in Higher Education (2020). Toolkit to support quality assurance agencies to address academic integrity and contract cheating. TEQSA

Rundle, K., Curtis, G., Clare, J., & Bretag, T. (2020). Why students choose not to cheat. In A Research Agenda for Academic Integrity (pp. 100–111). Edward Elgar Publishing. doi.org/10.4337/9781789903775.00014

Struyven, K., Dochy, F., & Janssens, S. (2005). Students’ perceptions about evaluation and assessment in higher education: A review. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(4), 325-341.

Media Attributions

- Academic misconduct types © Image generated by Napkin AI is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Covid-19-Cheese-Model-animation-02-short_frame © Siouxsie Wiles & Toby Morris adapted by Antonella Strambi is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Academic integrity layers © Generated using Napkin.ai is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Private: UniSA Logo