Part 1 – Teach

6 Giving Good Feedback Online

Kat Kenyon

In a Nutshell

The art of giving feedback online differs significantly from face-to-face settings. Without visual or audible cues, the context of feedback can be lost. This chapter explores methods for effectively communicating and providing feedback to online learners, focusing on how to leverage online tools to your advantage.

Why Does it Matter?

Learning online can often feel isolating. Impersonal, generalised, or copy-paste messages can exacerbate these feelings. If you’ve ever received a generic reply that seemed like the person hadn’t read your email, or just a “good job” on a paper you worked hard on, you’ll understand the frustration. Communication without visual, physical, or verbal cues is open to interpretation based on a person’s state of mind, cultural mindset, or language proficiency; this can lead to misunderstandings and misinterpretations, and cause frustration for both students and educators.

What does it look like in practice?

In this section:

- Best Practice Ideas for Providing Feedback Online

- How to Deliver Feedback Online

- LMS Tools for Feedback Delivery

Best Practice Ideas for Providing Feedback Online

Providing feedback online that is timely, positive, and effective is a valuable skill for educators (Leibold & Schwarz, 2015). In the online environment, timing is everything and students expect a fast turn-around for feedback. In face-to-face teaching, feedback is often provided informally during tutorials, practicals, workshops, and group activities. The lack of traditional classroom time in online teaching and the absence of visual cues can compel students to expect more frequent feedback from staff (Sorensen & Baylen, 2009). In the online environment, where most activities are asynchronous, this is harder to achieve. As a result, students often report less than satisfactory feedback in online courses (Soon, Sook, Jung & Im, 2000).

Leibold & Schwarz (2015) outline seven methods for providing feedback online:

- Address the learner by name

- Provide frequent feedback

- Provide immediate feedback

- Provide balanced feedback

- Provide specific feedback

- Use a positive tone

- Ask questions to promote further thinking

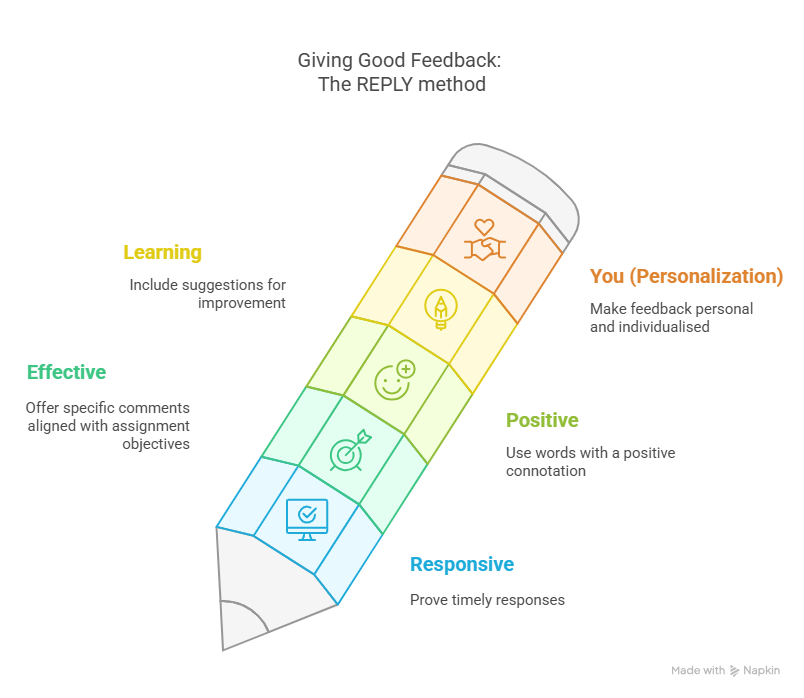

Another way to approach providing online feedback is using the ‘REPLY’ method:

Responsive: Provide a timely response to student questions.

Effective: Offer specific comments aligned to the assignment’s objectives.

Positive: Use words that give off a positive connotation.

Learning: Include suggestions for how the assignment can be improved.

You: Make it personal and not just a standard response.

(Project Lead the Way, 2022)

Just as you might set office hours for your face-to-face students, it’s important to set virtual office hours where students can ‘drop in’ via video or online chat to receive direct feedback. Spend these virtual office hours being active on the forums, providing feedback using the formats we’ll discuss in the next section. Communicate your virtual office hours to your students via the course site, and include a link for video drop-ins. If you’re unable to stick to your plan for whatever reason, don’t panic! Communicate any delays with your students – they will appreciate your honesty.

The modality of feedback is as important as the message. In a 2015 research paper by Henderson and Phillips on the trial of video-based feedback in formative assessments, students were not only overwhelmingly positive about this form of feedback – there were dozens of unsolicited emails or forum posts where the students responded to the online educator about their feedback – 98% of these responses were positive. Research has also shown that audio files that the student can download make the context of the feedback much clearer and indicates a level of detail and personalisation that is difficult to capture in written feedback (Maher Palenque, 2016).

In the next section, we look at how these ideas can be applied to the delivery of online feedback in more detail.

How to Deliver Feedback Online

Marking student work and giving feedback are arguably where academic staff spend a vast amount of time and energy. There is no one-size-fits-all model for online feedback. Let’s look at seven suggested ways of delivering feedback to your online students (click on each heading to reveal the description).

1. Mini Weave

Mini weaves can take a bit of time initially but are a great way to provide feedback to an entire class or a small group. A mini weave is essentially a summary of discussions around a particular topic, such as forum posts, replies to a posed question(s), or responses to a learning activity. In the classroom, it is the equivalent of summarising discussions at the end of a tutorial or seminar.

In a mini weave, you don’t need to summarise everything that is discussed, but instead recap the key or common themes throughout the discussion. Identify a key takeaway for the students to remember, and finish up your mini weave with a stimulating question for further discussion. This will give you an opportunity to see how well your students are engaging with the content at a deeper level, and develop a sense of belonging in the course. Mention students by name where possible.

Refer to Boettcher, J.V. & Conrad, R.-M. (2016). CB Tip 14: Discussion Wraps: A Useful Cognitive Pattern or a Collection of Discrete Thoughts? In The Online Teaching Survival Guide: Simple and Practical Pedagogical Tips (pp. 160-162) for more guidance around mini weaves.

2. Audio

Audio recordings are a powerful feedback mechanism that can help students better understand the context of your comments. Students can pick up on your tone, emphasis, and other cues that written feedback cannot convey. If you’ve never recorded audio feedback before, it may be useful to write out a script for your feedback. Be aware of any restrictions on the maximum time for audio recordings in your learning management system. This will help keep you on track and ensure you address all the main points of your feedback. Once you are well-versed at recording audio, this can often be quicker than written feedback (Maher Palenque, 2016), and it further builds your relationship with the students.

Lunt and Curran (2010) found that audio feedback is at least ten times more likely to be opened than written feedback. Be mindful, however, of hearing-impaired and Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) students in your course, who might find it more challenging to process information delivered through speech. In setting expectations for the course at the beginning of the study period, advise students if you plan to use audio feedback, and advise that alternative methods of feedback can be provided as needed.

Consider using audio feedback for formative assessment as well as summative. For example, why not record your mini weave as an audio file and post it to the course site.

3. Video

Video feedback, like audio, can pick up on nonverbal cues that assist students with understanding feedback. McCarthy’s study (2020) noted that 94% of students responded favourably towards video feedback for future courses. The overwhelming majority (94%) of respondents in the student evaluation of teaching in McCarthy’s (2020) research stated that the video feedback was helpful and constructive, with 95% of respondents noting the video feedback as a key indicator for course quality. Students in the survey did remark that not knowing their assessment grade until the end of the video was nerve-wracking; however, by sharing their grade first, you risk the student not listening to your carefully crafted feedback!

As with audio feedback, make sure your video is accessible, and provide an alternative feedback method for students with vision or other impairments. Some students may not have access to high-speed internet, so make sure if you use video feedback it is short and precise, to keep the file size small.

4. Rubrics

You might find that the term rubric is sometimes used interchangeably with the term marking guide, but they are in fact different. A marking guide is a set of criteria with simply a number assigned to each criterion. A rubric includes detail describing the learning criteria and level of quality they will be assessed on, giving students the opportunity to review their own work against the rubric prior to submission. A completed rubric that is provided to students with their marked assessment piece can show students where their strengths are, and perhaps where they need to spend more time refining.

5. One-to-One Feedback

This is perhaps the most conventional form of feedback. In on-campus courses, it may look like talking to students individually during or outside scheduled classes, meetings during consultation hours, or over email. In the online environment, this might look a bit different. Face-to-face meetings might be replaced with Zoom, and there may not be opportunities for informal discussions after a synchronous activity.

Here you can use the tools offered to you by your learning management system (LMS) to your advantage. Many online tools are available in LMSs that integrate feedback on student performance to replicate the type of learning conversations that teachers and students would normally have in the classroom. These tools can allow students to select an answer option from a list before receiving feedback, make decisions and experience the consequences as feedback, or require students to provide extended responses before receiving feedback. Provide formative learning activities as a way to replace the learning conversations that you would normally have with students in and around your face-to-face teaching. Formative activities can remain a part of your course website going forward, providing future students a blended learning experience that will require little ongoing maintenance or facilitation from the teaching team.

Using the tools available within your LMS (and other supporting tools offered by your institution) is a low-effort, high-impact way to build your teaching presence in the course and allows you to access data analytics to see if your students are really engaging with and understanding the content. This puts you on the front foot as to where students may be struggling to understand concepts and need extra support.

6. Group Feedback

Group feedback doesn’t just refer to group assessments. For example, a mini weave is a type of group feedback. If you provide a reflection point for students to submit anonymous feedback on how they found the week’s content, you can summarise this feedback and announce it to your students, providing your response to the issues raised. This adds to your teacher and social presence and shows students that their feedback is received and acted upon.

Race (2020) suggests providing “generalised group feedback on the key learning areas that affect most students within one week of the assessment”. This gives students the opportunity to benchmark their work against other students’ when they receive their individual feedback, without singling out any students who may be struggling.

7. Peer Feedback

Peer feedback allows students to learn from each other’s successes and weaknesses. It also allows students to develop their own feedback skills and learn more deeply (Race, 2020).

If setting up this type of feedback, ensure you provide students with the tools they need to offer constructive feedback. An example of how this might be done is to provide students with a rubric and an example of the rubric used in the provision of feedback for an example assessment.

LMS Tools for feedback delivery

Learning Management Systems (LMS) offer a variety of tools that can be used to give feedback or have automatic feedback mechanisms built in. Some of the tools that may be available to you include:

- Forums: Ideal for a mini-weave, or to probe how well your students are engaging with the course content at a deeper level.

- Audio and Video Recording: You can make quick videos that can be embedded in a text area, in a forum, or as assessment feedback. Students can pick up on your tone, emphasis, and other cues that written feedback cannot convey. This is particularly useful if there is something tricky you want to communicate. Your LMS may only allow a limited duration, so write yourself a script beforehand to keep to the point and to the time.

- Dialogue: With this tool, educators and students can start a dialogue with another person in the course. All the dialogue activities are logged, and email is not required. This is especially useful when there are multiple educators in the course. All educators can see and participate in the Dialogue conversations. This is useful if an educator has an unexpected absence. It also saves email space!

- Chat: This tool enables group or one-to-one real-time discussion that can be repeated or used as a one-time activity. Think of the tool like office drop-in hours. You can note your availability on the course site and then log on and wait for students to initiate contact.

- Scheduler: Allows you to specify specific timeslots that you are available, and then students can choose a timeslot in advance to speak with you. Think of this tool like setting office hours, but on your course site instead of on your office door! You may be able to record notes from the meeting in the tool – a handy way to keep all your student notes in one location, accessible from anywhere. Scheduler can accommodate multiple students, so you could also use this tool for students undertaking group work to get in touch with you.

- Quiz: This tool lets you automatically include general feedback or specific feedback for each question and each multiple-choice option. This is a low effort, high impact way to provide feedback and encourage student learning, as discussed earlier in this chapter.

- H5P: Several H5P content types allow for in-built feedback, such as Branching Scenario, Dialog Cards, Drag and Drop, Drag the Words, Essay, Flashcards, Hotspots, and Quiz. Some of these content types take more time to set up than others, and staff can consult with a Learning Designer for assistance.

At UniSA…

The Assessment Policy and Procedures sets out the purpose and features of assessment at UniSA. These documents set out what constitutes quality feedback and define that students must receive feedback on summative assessment within ten working days, and no later than 15 working days from the assessment deadline for submission. This applies to both on-campus and online courses, to ensure the feedback provided to students can be incorporated into their future work.

Knowledge Check – What Did You Learn?

Here are some comprehension check questions to reinforce what you’ve learned:

What Does It All Mean for Me?

Reflect on the feedback methods discussed in this chapter. Choose one method that you have not yet used in your teaching practice. Plan and implement this new method in your next course. Consider the following:

- Why did you choose this method?

- How will you implement it?

- What are your expectations for student engagement and learning outcomes?

After implementing this method, gather student feedback and reflect on its effectiveness. Adjust your approach as necessary based on this feedback.

References

Boettcher, J.V., & Conrad, R.-M. (2016). The online teaching survival guide: Simple and practical pedagogical tips (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

Henderson, M., & Phillips, M. (2015). Video-based feedback on formative assessments: Scaffolding learning and engagement. Instructional Science, 43(3), 305-329.

Leibold, L., & Schwarz, L.M. (2015). The art of giving online feedback. The Journal of Effective Teaching, 15(1), 34-46.

Lunt, T., & Curran, C. (2010). ‘Are you listening please?’ The advantages of electronic audio feedback compared to written feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(7), 759-769.

Maher Palenque, S. (2016). The power of podcasting: Perspectives of pedagogy. Journal of Instructional Research, 5, 4-7.

McCarthy, J. (2020). Student perceptions of screencast video feedback for summative assessment tasks in the creative arts. In C. Dann & S. O’Neill (Eds.), Technology-enhanced formative assessment practices in higher education (pp. 177-192). IGI Global.

Project Lead the Way. (2022). How to provide meaningful feedback in distance learning. Project Lead the Way Knowledge Center. Retrieved from https://knowledge.pltw.org/s/article/How-to-Provide-Meaningful-Feedback-in-Distance-Learning

Race, P. (2020). The lecturer’s toolkit: A practical guide to assessment, learning and teaching (4th ed.). Routledge.

Sorensen, C., & Baylen, D. (2009). Learning online: Adapting the seven principles of good practice to a web-based instructional environment. In A. Orellana, T. L. Hudgins, & M. Simonson (Eds.), The perfect online course: Best practices for designing and teaching (pp. 69–86). Information Age Publishing Inc.

Soon, K. H., Sook, K. I., Jung, C. W., & Im, K. M. (2000). The effects of internet-based distance learning in nursing. Computers in Nursing, 18, 19-25.

Media Attributions

- Giving Good Feedback | The REPLY method © Generated with Napkin.ai is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Private: UniSA Logo