Part 2 – Design

18 Weaving Aboriginal Knowledges across the Curriculum

Courtney Theseira; Kirrakee Watson; Kath Francis; and Karen Sinclair

In a Nutshell

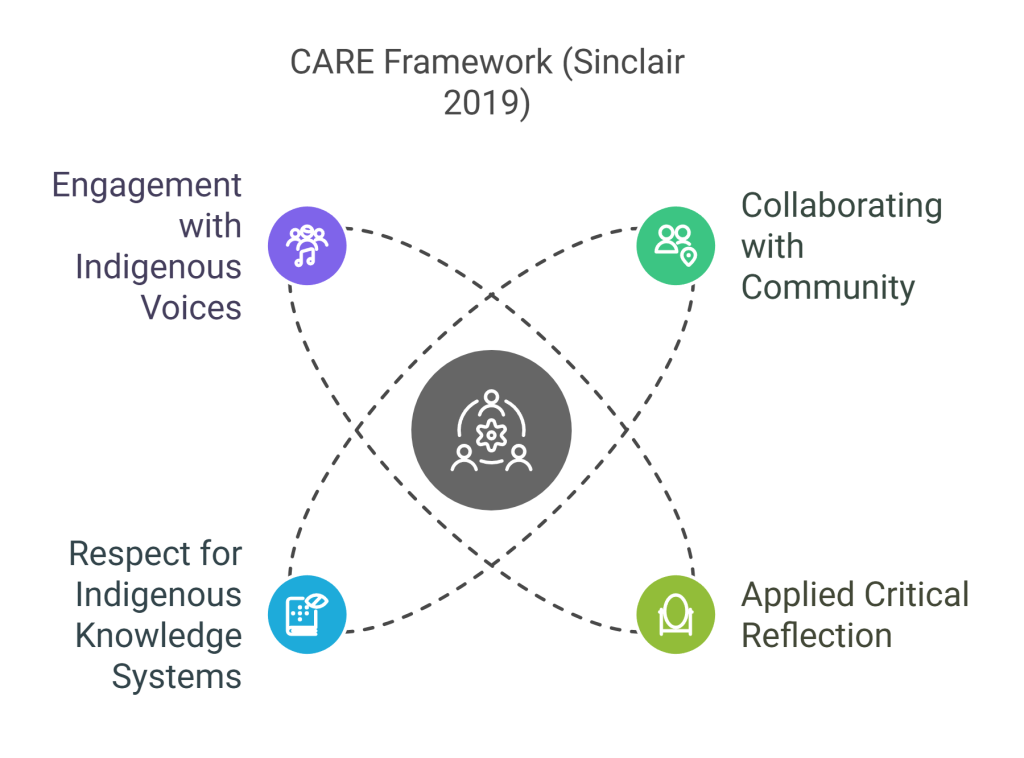

Integrating Aboriginal Knowledges into higher education cultivates complex thinking and diverse learning experiences within degree programs. This requires a foundation of cultural safety, ensuring that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples feel respected and valued. To authentically embed Aboriginal perspectives, it is essential to acknowledge historical injustices and actively challenge discrimination, creating an empowering environment for all. The CARE Framework by Karen Sinclair (2019) provides a roadmap for this integration, focusing on collaborating with communities, engaging in critical self-reflection, respecting Aboriginal knowledge systems, and amplifying diverse Aboriginal voices.

Why Does it Matter?

For students, especially Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students, to feel safe within the University classroom, there needs to be Aboriginal Knowledges existing alongside Western Knowledges. The Behrendt report highlights the need for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander policies and programs to support their involvement in universities (Behrendt, Larkin, Griew, & Kelly, 2012). Furthermore, Universities Australia policy expects students to graduate with experience in Aboriginal knowledges and practices, making it essential for curriculum designers to consider this topic (Universities Australia, 2022).

The content of this chapter is geared primarily toward Australian readers, but the principles and practices discussed will be applicable across any nation with a colonising history. By incorporating Indigenous perspectives and creating culturally safe learning environments, educators everywhere can contribute to reconciliation efforts and support the wellbeing and success of Indigenous students.

What Does it Look Like in Practice?

Dr Uncle Lewis Yarlupurka O’Brien, a Kaurna Elder in Residence at UniSA, shares his Kaurna perspective on teaching and learning, highlighting the ‘two-ness’ of education. He explains that if you give a child a piece of string, they will observe and play with it. Teach them a game using the string, and their learning expands; change the game’s rules, and the child will adapt. This reflects the concept of Nindi – the Kaurna term for ‘becoming’ or ‘transferred into’ – which emphasises education as a two-step process: theoretical teachings and practical application. Teaching, the finite first step, provides knowledge, while learning, the second step involving hands-on experience, is limitless. Uncle Lewis’ story reminds us that education must guide and teach, but its journey is continuous, grounded in action and growth.

When applied to teaching and curriculum, this perspective underscores that while theoretical knowledge lays a foundation, true learning flourishes through practical engagement. Embedding this Aboriginal concept of Nindi into curriculum design allows educators to create learning experiences that not only convey Aboriginal knowledges but also encourage action, reflection, and connection. For instance, students might engage in projects co-designed with Aboriginal communities, participate in on-Country learning, or contribute to initiatives supporting cultural sustainability. This dynamic approach transcends static content delivery, fostering an active reconciliation journey within education that aligns with Uncle Lewis’ vision of limitless, transformative learning.

When it comes to integrating Aboriginal Knowledges into the curriculum, there must be a foundation of cultural safety. Only after this has been successfully embedded into the curriculum can the CARE framework be applicable, as it directly refers back to cultural safety. The following sections will discuss how cultural safety can be implemented into the curriculum and provide practical examples of how the CARE framework can be embedded.

In this section:

- Cultural Safety

- The CARE Framework

- Collaborating with Community

- Applied Critical Reflection

- Respect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Knowledge Systems

- Engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voices

Cultural Safety

For Aboriginal Knowledges to be woven through the curriculum successfully, there first needs to be a focus on cultural safety. Before content can be included and discussed in various spaces across the University, there needs to be an understanding that every Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person in that room has the right to be culturally safe.

Cultural safety is a concept deeply rooted in the acknowledgment of historical injustices and the unique cultural identities of Australia’s Indigenous peoples, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. It recognises that healthcare, educational, and institutional systems have often perpetuated harm and discrimination against these communities. Cultural safety goes beyond cultural competence; it emphasises creating an environment where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students, staff, and community members feel valued, respected, and empowered. It involves actively challenging discrimination, bias, and systemic racism while ensuring that educational institutions promote cultural inclusivity and equity. For Indigenous peoples, cultural safety is not just about cultural sensitivity but a fundamental requirement for their well-being, health, and educational success (Bin-Sallik, 2003).

Integrating cultural safety into higher education curriculum is essential for several reasons:

1. Reconciliation and Social Justice: It contributes to reconciliation efforts and the broader social justice agenda in Australia by acknowledging the historical and ongoing impacts of colonisation and promoting cultural safety, fostering understanding and respect for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and their cultures.

2. Sense of Belonging: It fosters a sense of belonging among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students, which is crucial for their academic success and overall well-being (Carter et al., 2017). A culturally safe curriculum can help reduce the alienation often experienced by Indigenous students and encourage their active participation in higher education.

3. Preparing All Students: It prepares all students, regardless of their background, to work effectively in a diverse and interconnected world, equipping them with the skills and awareness needed to engage respectfully with Aboriginal communities.

The CARE Framework

The CARE Framework, developed by Karen Sinclair (2019), provides a structured approach for integrating Aboriginal Knowledges into university settings. It encompasses four key themes: Collaborating with Community, Applied Critical Self-Reflection, Respect for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Knowledge Systems, and Engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voices.

Collaborating with Community

When placing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge within a university setting, it should always be done in collaboration. Aboriginal Knowledges cannot be replicated by non-Indigenous people, which is why there should always be a member of the community involved. This involves understanding the engagement protocols of the country that you are in. For the University of South Australia, this is outlined in the Yurirka: Proppa Engagement with Aboriginal Peoples (Office of Aboriginal Leadership and Strategy (ALS, UniSA), 2021) document, which provides guidance on how to engage with the community and what protocols need to be followed.

Collaborating with the community also includes ‘both ways’1 learning. This means that Aboriginal Knowledges should have an equal place within the curriculum. Aboriginal and Western knowledges should coexist, intertwining and being held at the same level. Combining these knowledges creates a ‘both-ways’ learning environment, where shared learning is experienced (Ober & Bat, 2007). The framework encourages ongoing reflection, questioning, and deepening understanding, providing opportunities for individuals to question their cultural knowledge and capability within the space (Sinclair, 2021).

Applied Critical Reflection

Critical reflection involves self-assessment of one’s actions in Aboriginal contexts, encompassing cultural introspection and the influence of culture on identity, which can be done through positionality. Positionality acknowledges personal biases shaped by social, cultural, and political positioning, differing from Indigenous Standpoint Theory, which recognizes unique Indigenous perspectives (Duarte, 2017; Nakata, 2007). Notably, positionality counters colonial biases and offers inclusivity absent in Indigenous Standpoint Theory (Morton-Robinson, 2014).

Australian Aboriginal identity, imposed by non-Aboriginal authorities, is considered othering and colonial, making positionality, rooted in personal experience, more suitable. Educational programs should introduce Positionality and Indigenous Standpoint Theory, emphasizing self-awareness and understanding of cultural influences. Incorporating diverse curriculum methods like case studies fosters cultural sensitivity and challenges biases, promoting self-reflection and cultural capability.

Respect for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Knowledge Systems

Respecting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Knowledge Systems goes beyond merely including them in your courses. There needs to be consideration into what can be shared in a culturally respectful way. Intellectual property rights of Aboriginal Knowledges must also be respected. There should be no assumption that everything is open knowledge but care and consideration into what is being shared. Aboriginal Knowledge is not open knowledge and should be referenced in the same way as Western Knowledge. Within universities, there should not be an assumption that this content, data, or information can belong to the university (Janke, 2021). Aboriginal Knowledge should and will always be owned by the community that generated it (Janke, 2021; Maiam Nayri Wingara, 2018).

Engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voices

The pluralisation of voice should be noted. While there is often an expectation that including one Aboriginal voice in the university curriculum is sufficient to ensure representation, this is incorrect. There must be multiple voices as there is not nor will there ever be only one Aboriginal experience. Each mob, each community, and each person will have different standpoints. Disaggregating the experience of Aboriginal people shows a deep understanding of the multiple narratives that exist in this country now known as Australia. It also enables the application of Aboriginal Knowledge Systems to learning design, as multiple Aboriginal Knowledge Systems will be present in a course.

At UniSA…

UniSA has a long history of Aboriginal engagement and achievement. In 2002, the Aboriginal Curriculum in Undergraduate Programs (ACUP) initiative began with the intention of encouraging academics to explore and develop Aboriginal pedagogies and curricula. This initiative aimed to inform the development of guidelines to support the embedding of Aboriginal content in programs, thereby exposing all students to Aboriginal Knowledges. UniSA has recently reached the implementation stage, where academic staff are beginning to utilise ACUP strategies within current courses and programs.

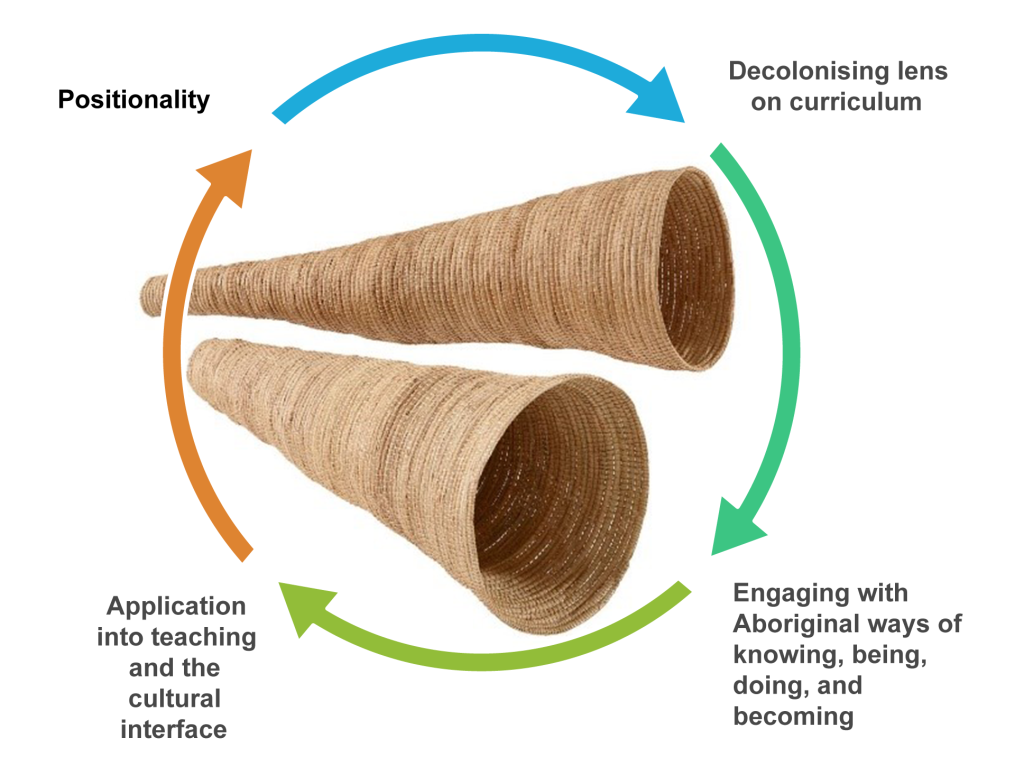

This is achieved through the creation of the Decolonising Higher Education workshops developed by the Teaching Innovation Unit. These workshops explore four main themes as starting points for educators to include Aboriginal knowledges in their courses or programs. The themes are:

Positionality

Decolonial Epistemology

Aboriginal Knowledges and Teaching Approaches

Application of Aboriginal Knowledges

Upon completing this workshop series, there is an expectation of constant critical self-reflection, ongoing work, and consistent forward action. This approach creates the spiral weave depicted in Figure 2

Knowledge Check – What did you learn?

What Does It All Mean for Me?

Reflecting on this chapter, consider how you can apply the principles of weaving Aboriginal Knowledges into your courses or programs. Here is an activity to help you integrate these concepts:

Activity: Weaving Aboriginal Knowledges into Your Teaching Practice

Using the strategies discussed in this chapter, create a plan to weave Aboriginal Knowledges into one of your courses or programs. Follow these steps:

- Consider Your Positionality:

- Reflect on your own cultural lens, lived experiences, and biases. Understand how these influence your teaching and the resources you choose.

- Engage in ongoing self-reflection to decolonize yourself and your work.

- Embed Aboriginal Knowledge Throughout the Course:

- Ensure that Aboriginal Knowledge is woven throughout the course, rather than confined to a single section.

- Include applicable readings by Aboriginal authors, experts, and information that relate to the course content.

- Utilise Institutional Resources:

- Identify existing policies, frameworks, graduate qualities, or knowledge within your institution that can inform your teaching practice.

- Leverage institutional resources to enhance your understanding and integration of Aboriginal Knowledges.

- Engage in Continuous Self-Reflection:

- Regularly reflect on your teaching practices and the integration of Aboriginal Knowledges.

- Continuously update and improve your course content to ensure it remains relevant and respectful.

- Apply the CARE Framework:

- Use the CARE Framework to guide the weaving of Aboriginal Knowledges in your course.

- Collaborate with community members, engage in applied critical self-reflection, respect Aboriginal Knowledge Systems, and include multiple Aboriginal voices.

Reflection:

After implementing your plan, reflect on the following questions:

- How did the integration of Aboriginal Knowledges impact student engagement and understanding?

- What feedback did you receive from students and community members about the changes you implemented?

- What adjustments can you make to further enhance the learning experience and support cultural safety?

Use the H5P Documentation tool to outline your integration plan and download your text and ideas via the Text Export page.

References

Behrendt, L., Larkin, S., Griew, R., & Kelly, P. (2012). Review of higher education access and outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People: Final Report. Canberra: Australian Government.

Carter, J., Hollinsworth, D., Raciti, M., & Gilbey, K. (2017). Academic ‘place-making’: Fostering attachment, belonging and identity for Indigenous students in Australian universities. Teaching in Higher Education, 23, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1379485

Duarte, M.E. (2017). Network Sovereignty: Building the Internet Across Indian Country. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Janke, T. (2021). True Tracks: Respecting Indigenous Knowledge and Culture (1st ed.). NewSouth Publishing.

MnW Principles. (2018). Maiam Nayri Wingara. Retrieved 21 November 2024, from https://www.maiamnayriwingara.org/mnw-principles

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2013). Towards an Australian Indigenous Women’s Standpoint Theory: A Methodological Tool. Australian Feminist Studies, 28(78), 331–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2013.876664

Nakata, M. (2007). An Indigenous Standpoint Theory. In Disciplining the Savages: Savaging the Disciplines. Aboriginal Studies Press. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.208224435424405

Ober, R., & Bat, M. (2007). Paper 1, Both-ways: The philosophy. Ngoonjook: A Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues, 18,13-79

Sinclair, K. (2019) Aboriginal Content in Undergraduate Programs (ACUP) External Evaluation. Literature Review. Aboriginal Leadership and Strategy. University of South Australia.

Sinclair, K. (2021). Disrupting normalised discourses: ways of knowing, being and doing cultural competence. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2018.23

Media Attributions

- CARE framework © Generated using Napkin.ai is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Private: UniSA Logo

- Weaving Aboriginal Knowledges © Jenni Carter