Part 1 – Teach

9 Teaching Students from Diverse Cultural Backgrounds

Antonella Strambi

In a Nutshell

Global mobility and online teaching and learning increase cultural diversity in university classrooms. Viewing the classroom as a multicultural community enables us to employ frameworks and resources developed to make sense of intercultural encounters and avoid misunderstandings. In this chapter, we use these frameworks to suggest ways to maintain positive teacher and social presence in the culturally diverse classroom and support student learning. We also highlight strategies for minimising the risk of mismatched expectations when working with students from diverse backgrounds, especially when teaching online.

Why Does it Matter?

Teaching culturally diverse groups can be highly rewarding; however, we must also be mindful of the challenges that intercultural communication may bring. Online teaching can be even more challenging from this perspective. The paucity of non-verbal cues – in synchronous (e.g. Zoom) as well as written communication (such as email and discussion forums) – may give rise to misunderstandings, which in turn can affect teacher-student relationships in the online classroom. Therefore, it is important to consider ways in which cultural diversity can be valued and supported through intentional and culturally-aware learning design, both face to face and online.

What does it look like in practice?

In this section:

- Understanding culture and behaviour

- National culture – Hofstede’s 6D Model

- Inter-cultural – The Somethings Up! Cycle

- Dealing with cultural differences in the online classroom

- Intercultural Teaching Strategies

Understanding culture and behaviour

Defining ‘culture’ is not a simple task. Although ethnic background may be the first thing that comes to mind, there are many more subtle axes of cultural variation. For example, communication expert Deborah Tannen (1997) suggests that gender can be considered a sub-culture, and that misunderstandings between men and women can be attributed to different styles of communication that are culture-bound. Online communication tools and environments also come with their own norms and expectations regarding users’ behaviours (Thorne 2003), which – when not adhered to -can create communication challenges. Likewise, attaining membership in the academic community can itself be challenging to students from lower socio-economic backgrounds who may not have the ‘cultural capital’ (Sullivan 2001) that comes from a family history of academic engagement.

Cultural variation can contribute to breakdowns in communication, as individuals from diverse backgrounds may employ different ‘codes’ and thus make incorrect assumptions and interpretations of other people’s behaviours. Developing awareness of our own cultural frames is the first step toward successful intercultural communication, as we become mindful of bias we might apply when making sense of our interactions with students.

National culture – Hofstede’s 6D Model

International students at Australian universities are drawn from many countries. While national culture is a contested concept in academia, nationality remains a common lens through which we understand cultural differences.

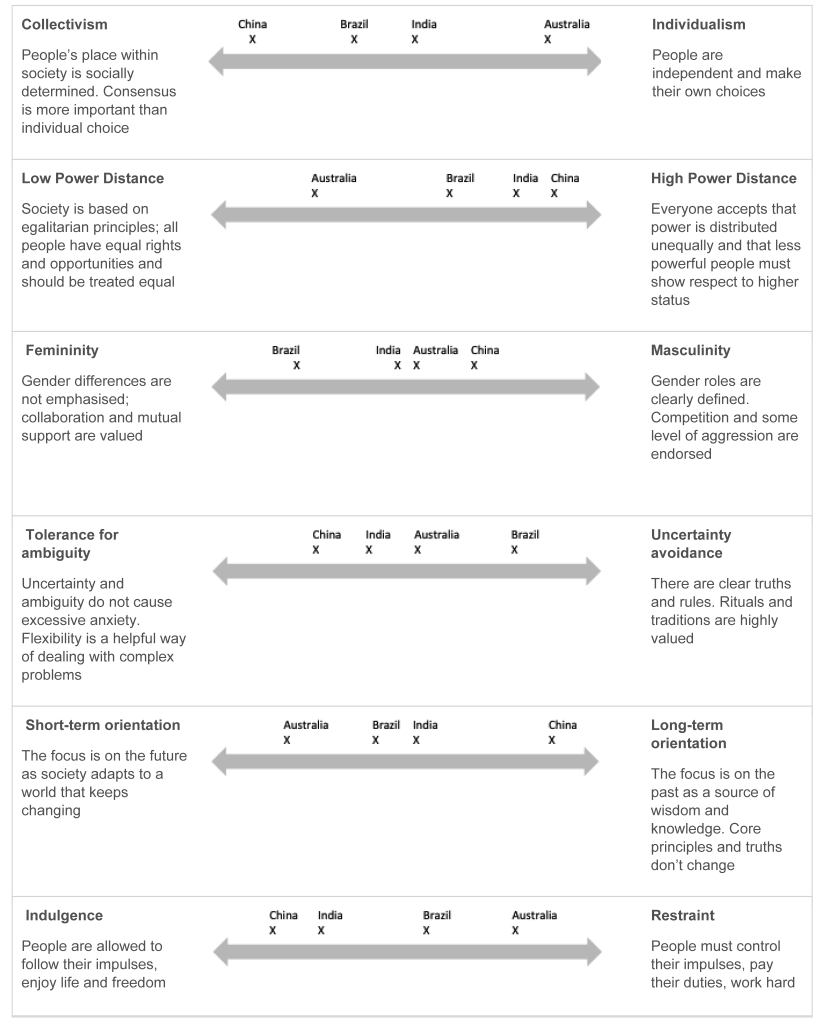

One of the many attempts to facilitate comparisons between national cultures is Geert Hofstede’s (1991) 6-dimensional model. Figure 1, below, shows the ‘scores’ given by Hoftstede to each of the 6 dimensions – for Australia, as well as China, India, and Brazil. (Detailed descriptions of the 6 dimensions can be found on Hofstede’s website). The model is intended to help us form hypotheses about the ‘underlying frames’ of reference that shape our students’ assumptions and values, so that we can identify potential sources of miscommunication.

However, this model of culture has limitations. The relationship between values, norms, and behaviours is not a linear one. The same value – for example, showing respect for authority – may be realised through different behaviours. In other words, what is considered ‘respectful’ behaviour in one culture may be interpreted as disrespectful in another, even though individuals’ values and intentions are the same – i.e., showing respect.

By making assumptions based on national cultural frames, we may fall into the trap of stereotyping. To avoid negative stereotyping, it is important to keep in mind that:

- There are often more similarities than differences across groups. Focusing on the differences can lead to separation and conflict, rather than connection and mutual understanding.

- Individuals often belong to several different groups and their level of identification and compliance with their groups’ values and norms may also vary. Therefore, assuming that someone will behave in a certain way just because we identify them as a representative of a particular group can be very misleading.

Inter-cultural – The Something’s Up! Cycle

A useful framework to interpret encounters between cultures while avoiding erroneous assumptions based on stereotyping is the ‘Something’s up! Cycle’ developed at Norquest College (Apedaile 2015)

The framework can be used whenever we experience confusion, uncertainty, frustration, or other emotions in response to another person’s behaviour and we struggle to understand their behaviour from our own perspective.

The first step in the Something’s Up! Cycle (Figure 2) is recognising an incident as a potential cultural misunderstanding and describing the event as well as our experience of it (i.e., answer the questions: What happened? How did I feel?)

It is important to suspend judgement and be mindful of our first ‘instinctive’ response. In other words, we must avoid jumping to conclusions based on our own interpretations.

We can then begin making sense of the event by bringing to awareness our expectations and identifying what it was, exactly, that triggered our emotions.

The following step then involves taking informed action, which may simply mean asking questions to gather the other person’s perspective on the event or changing our own behaviour and/or expectations. In this case, a new cycle will start that would involve evaluation of the effect of these changes.

Dealing with cultural differences in the online classroom

The Something’s Up! Cycle can be used any time a student’s behaviour does not meet our expectations and we suspect this may be due to a cultural misunderstanding.

To inform the ‘Make Sense’ and ‘Informed Action’ stages, we might refer to Hofstede’s 6 dimensions of national culture. We can also identify other potential sources of misunderstanding. These include:

- the degree of directness and confrontation that is acceptable in interaction;

- differences in time orientation and nonverbal communication patterns;

- attitudes toward silence and interruption in oral conversation; and

- linear versus circular communication paths.

A summary of the features of these and other cultural orientations is available in the Scene-by-Scene Breakdowns booklet produced as part of Norquest College’s Critical Incidents for Intercultural Communication in the Workplace resource (2015, pp. 44-47).

Ideally, developing our intercultural sensitivity and competence should allow us to prevent many cultural misunderstandings. If we consider a student cohort as a community, it is easy to see how it is important to build a shared understanding of desirable behaviours and expectations. For example, developing netiquette guidelines collaboratively could be one of the first orientation activities for online classes. Rather than provide generic statements (e.g. ‘be respectful’), we could ask students to describe observable actions that are consistent with values and norms (e.g. ‘do not interrupt’), so that any mismatched expectations can be identified and addressed.

Establishing an overall culturally inclusive teaching and learning environment will also develop students’ intercultural sensitivity and competence. Dimitrov and colleagues (2014) suggest adopting the following 13 Intercultural Teaching Strategies for this purpose:

- Perspective Taking: Model and encourage students to engage with viewpoints different from their own.

- Non-Judgemental Discussion: Promote respectful and open conversations about cultural and social differences.

- Diverse Communication: Facilitate discussions that accommodate various communication styles.

- Inclusive Environment: Create a learning space that welcomes and supports all students and recognise any potential barriers to participation.

- Appreciate Differences in Teaching and Learning: Acknowledge unique perspectives and experiences of teaching and learning and student-educator roles and relationships

- Culturally Sensitive Feedback: Provide feedback in a way that is culturally appropriate and understandable.

- Tailored Messages: Adjust communication to accommodate different language abilities.

- Cultural Context: Explain unspoken cultural and academic assumptions to students.

- Culturally Valid Assessments: Design assessments that acknowledge and respect diverse writing and communication styles.

- Tolerance for Ambiguity: Help students identify and resolve ambiguities caused by different communicative styles (e.g. circular v linear)

- Identify Risk Factors: Recognize potential challenges faced by specific student groups. Consider risks such as loss of face, conflict avoidance, etc.

- Student Interaction: Foster opportunities for students to learn from each other’s experiences and cultural knowledges.

- Cultural Awareness: Reflect on your own cultural biases and how they impact interactions with diverse students.

At UniSA….

The English Language and Intercultural Learning and Teaching (ELILT) framework and resources were developed at UniSA. The site provides curated materials on how to support students from diverse cultural backgrounds in their learning, including: academic reading and writing, oral communication, critical thinking, group work and research.

Knowledge Check – What did you learn?

What does it all mean for me?

- Can you see yourself thinking through the steps outlined in the Something’s up cycle, the next time you need to interpret a student’s behaviour that you find challenging?

- Of the 13 Intercultural teaching strategies proposed by Dimitrov and colleagues (2014), which ones resonate the most for you? And which are you already using in your teaching?

- Select one of the 13 Intercultural teaching strategies proposed by Dimitrov and colleagues (2014) that you feel you don’t use enough in your teaching, and consider how some of your curriculum or individual learning activities could be modified to incorporate it?

References

Apedaile, S 2015. The Something’s Up! Cycle, NorQuest Centre for Intercultural Education, < https://www.norquest.ca/NorquestCollege/media/pdf/centres/intercultural/CI/The-Somethings-Up-Cycle-Handout-Apr-2018.pdf >.

Dimitrov, N., Dawson, D.L., Olsen, K. and Meadows, K.N., 2014. Developing the intercultural competence of graduate students. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 44(3), 86-103.

Hofstede, G., (1991). Cultures and organizations : software of the mind. London: McGraw-Hill.

NorQuest College, 2015. Critical Incidents for Intercultural Communication in the Workplace. Scene-by-Scene Breakdowns, Edmonton. <https://www.norquest.ca/NorquestCollege/media/pdf/centres/intercultural/CI/Critical-Incidents-for-Intercultural-Communication-in-the-Workplace_Scene_by_Scene-Breakdowns.pdf >

Sullivan, A., 2001. Cultural capital and educational attainment. Sociology, 35(4), pp.893-912.

Tannen, D., 1997. You Just Don’t Understand. Estelle Disch (ed.), pp.186-191.

Thorne, S.L., 2003. Artifacts and cultures-of-use in intercultural communication. Language Learning & Technology, 7(2), pp.38-67.

Further Resources

There is a wealth of resources specifically designed to support educators teaching in intercultural contexts and to develop intercultural competence more broadly. Here are a few we recommend:

The International Education Association of Australia has developed a set of Good Practice Principles and Quick Guides for Learning and Teaching Across Cultures (2013). Quick guides are available for each of the following topics:

- Assessment

- Curriculum Design

- Developing English Language Skills

- Managing Group Work

- Professional Development

- Student Services

- Teaching

The section of the Globalization of Learning module developed by the Queen’s University at Kingston (Canada) includes sections on ‘Models of Inclusive and Intercultural education’ (including Indigenous), ‘Communication in the Intercultural Classroom’, and ‘Interculturalizing the Curriculum’. Scenarios are also provided which you can use to test your ability to interpret student behaviours that you may find challenging but that could be explained by intercultural differences.

The Critical Incidents for Intercultural Communication in the Workplace (2013-2015) set of resources developed at NorQuest College (Canada) offers numerous videos of scenarios representing misunderstandings due to differences in cultural orientations.

Media Attributions

- Collectivism

- The something’s up cycle © Apedaile adapted by Antontella Strambi

- Private: UniSA Logo