Main Body

4.2 Misleading or deceptive conduct and conduct likely to mislead or deceive

The majority of the High Court has noted that, as far as ACL s. 18 cases are concerned, “everything must depend on an appropriately detailed examination of the specific circumstances of the case”.[1] This means that, while guiding principles can be found in previously decided cases, and in the works of commentators, one must constantly be aware that each case is likely to be unique and must be analysed as such.

The terms “misleading” and “deceptive” are not defined in the ACL. However, by drawing upon a range of cases we can form an understanding of the types of conduct that these terms are intended to cover. In the context of s. 32 of the Consumer Protection Act 1969 (NSW), the Court in CRW Pty Limited v Sneddon[2] noted that to “mislead” is “to lead into error”.[3] In that case, a newspaper advertisement was capable of leading people to think that the transaction advertised was for a hire purchase or credit sale, rather than an outright sale. This test is widely accepted and could be said to constitute the minimum requirement for conduct to be misleading. However, in further defining what type of conduct is misleading or deceptive, it is to be noted that “[i]t is not sufficient if the conduct simply causes confusion or uncertainty”.[4]

The courts now also refer to the term “wonderment” as not amounting to misleading or deceptive conduct. The term was mentioned in Google Inc v ACCC at [8]:[5] ‘Third, conduct not causing confusion and wonderment is not necessarily co-extensive with misleading or deceptive conduct’. This passage is now commonly cited in subsequent cases. For example, the term is referred to in the recent case of ACCC v Kogan at [13]:[6] ‘The issue is not whether the impugned conduct simply causes confusion or wonderment’.

The definition of the term “deceptive” has gained an even lesser degree of judicial attention. The reason for this is illustrated in Gibbs CJ’s discussion in Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd[7] of the relation between misleading conduct on the one hand, and deceptive conduct on the other:

“Those words are on any view tautologous. One meaning which the words “mislead” and “deceive” share in common is “to lead into error”. If the word “deceptive” in s. 52 [ACL s. 18] stood alone, it would be a question whether it was used in a bad sense, with a connotation of craft or overreaching, but “misleading” carries no such flavour, and the use of that word appears to render “deceptive” redundant.”[8]

In other words, since the requirement for conduct to be regarded as “deceptive” is stricter than the requirements for conduct to be “misleading”, there is no real need to examine whether the relevant conduct meets the stricter test of being “deceptive”. It is, after all, sufficient that it meets the lower test of being “misleading” for ACL s. 18 to be applicable.

While the case law is not clear on this issue, it could perhaps reasonably be suggested that for conduct to be deceptive the offending party must have acted with intention. If so, when put in a mathematical expression it could be said that: deceptive conduct = misleading conduct + intention. There is, however, no authority to back this expression at this stage.

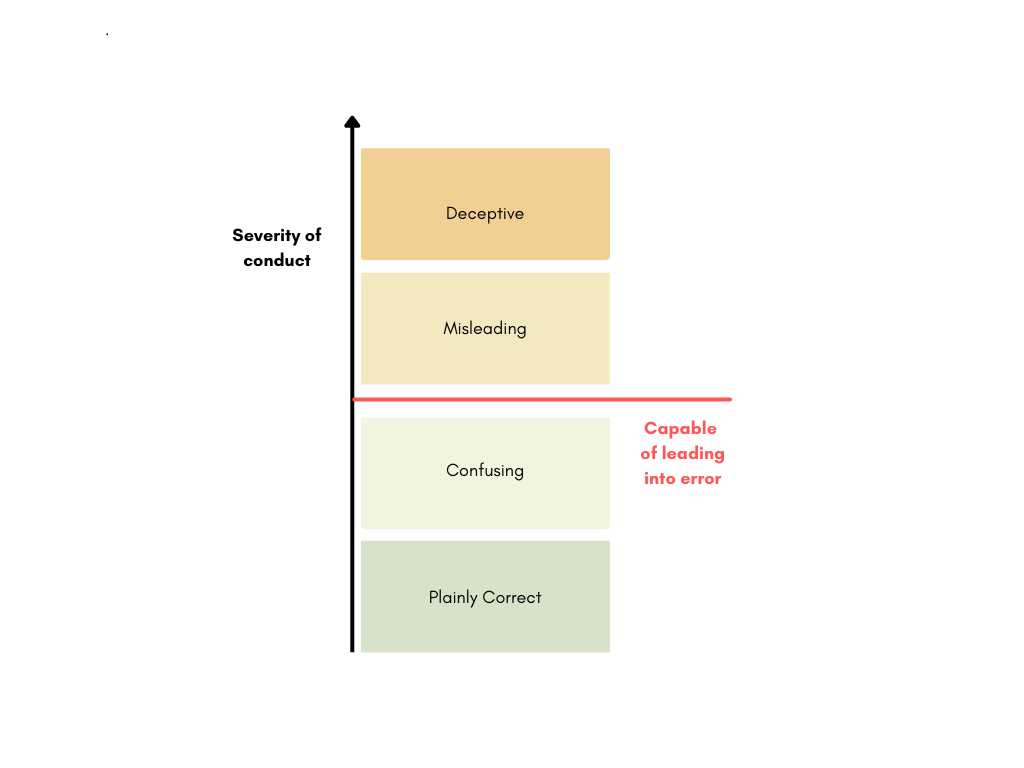

If presented as a diagram, the discussion above could be summarised in the following:

At the lowest end of the scale is conduct that is plainly correct (or in the case of so-called puff, plainly and obviously incorrect). Such conduct, and conduct that is merely confusing, is not capable of leading people into error. However, as soon as conduct is more severe than to merely be confusing, it is capable of leading people into error. As such, it meets the threshold test for being misleading and it may constitute a violation of ACL s. 18.

At the lowest end of the scale is conduct that is plainly correct (or in the case of so-called puff, plainly and obviously incorrect). Such conduct, and conduct that is merely confusing, is not capable of leading people into error. However, as soon as conduct is more severe than to merely be confusing, it is capable of leading people into error. As such, it meets the threshold test for being misleading and it may constitute a violation of ACL s. 18.

In distinguishing between confusing conduct on the one hand, and misleading conduct on the other, one could possibly point to a difference in the mind of the affected party. Put simply, a person that has been confused does not know what to think; she/he has not made up her/his mind. In contrast, a person that has been misled has formed an erroneous opinion; she/he has made up her/his mind.

As to conduct “likely to mislead or deceive”, the word “likely” has been said to refer to “a real or not remote chance or possibility regardless of whether it is less or more than fifty per cent”.[9] This should, however, not be seen as lowering the bar for what actually constitutes misleading or deceptive conduct. Indeed, perhaps it may be said that the words ‘likely to mislead or deceive’ do not add much to the section. However, the words ‘likely to mislead or deceive’ do emphasise that it is not necessary to prove that the conduct in question in fact deceived or misled anyone.

When assessing whether certain conduct is misleading or deceptive, it is important to have regard to the circumstances of that conduct. For example, in discussing alleged misleading or deceptive publications on a website, Tamberlin J (in Seven Network Ltd v News Interactive Pty Ltd) stated that:[10]

“In assessing what is conveyed by the web pages it is not appropriate to anticipate that every person viewing the site would take the time to analyse subtle merchandising or legal overtones or connotations, and the issue is largely one of transitory impression. If the material in question is continuously displayed and access to the site is frequent, as opposed to a one-off occurrence, then the impression will be reinforced.”[11]

In other words, a court will take account of how the medium conveying the misleading and/or deceptive conduct normally is approached. For example, where a webpage, or social media posting, contains misleading and/or deceptive information, it may not be sufficient that there is a link to another webpage (or other online resource) disclaiming the accuracy of that information. Similar reasoning can be applied in the context of, for example, TV commercials, newspaper advertisements and tabloid headlines.

If conduct is merely “transitory or ephemeral”, where any likely misleading impression is readily and swiftly dispelled, it will not constitute a contravention of s. 18.[12] For example, in the case of Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne v Powell,[13] the Court held that there would be no contravention of s. 18 where there has been potentially misleading conduct at the beginning of an event, but the erroneous impression that may have been caused is dispelled by the end of that event.[14]

In Seven Network Ltd v News Interactive Pty Ltd,[15] Seven Network sought to restrain News Interactive from displaying on their websites a banner, and other visual representation in substantially similar form to the banner, and the use of the words “Athens Olympics”, and representations of an “Olympic” torch in close proximity to the names and business-related logos of News. Seven wished to protect its investment in securing rights as the official broadcaster in Australia of the Olympic Games for which it had paid a substantial sum to secure these rights. The Court rejected Seven Network’s argument.

In addition, the Federal Court case of Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Trading Post Australia Pty Ltd[16] addressed whether ‘sponsored links’ in Google search results are misleading and deceptive under TPA s. 52 (ACL s. 18). In this case, the Trading Post signed up Google AdWords and, subsequently, a marketing agency retained by the Trading Post uploaded a number of keywords that were inserted into the headings of the Trading Post’s advertisements. The keywords that were uploaded were the names of car dealerships located in the Newcastle area and were not associated with the Trading Post.

The businesses complained to the ACCC, which subsequently took action against the Trading Post and Google. With respect to the case against Google, the Court held that Google sufficiently distinguished between search results and sponsored links, and further, that Google made no representations through the advertisements. The court found that ordinary and reasonable consumers would understand the concept of a ‘sponsored link’, and further that the advertiser, not Google, determined the content. It is also worth noting that Nicholas J found that TPA s. 85(3) defence [ACL s. 209], with respect to the business of publication of advertisements, would apply to Google had it been held to be liable for the representations.

The above decision was overturned in part by the Full Court of the Federal Court. In the appeal, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Google Inc,[17] the Court found that Google Inc could rely on the “publisher’s defence” in TPA s. 85(3) (ACL s. 209) in respect of particular AdWords and sponsored links. However, Google Inc was held to be unsuccessful in relying on the publisher’s defence in 4 other instances. These involved particular advertisers, who held Google AdWords accounts, using the names of their competitors as keywords to draw customers to their own site. The Court held that because Google Inc’s significant involvement in the process of selecting and approving the AdWords, and of controlling the Google search engine’s response to users’ searches, Google had engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct. This Full Federal Court decision has now been overturned by the High Court in Google Inc v ACCC.[18] The High Court did not determine whether Google Inc could have relied on the “publisher’s defence” because the Court held that Google Inc had not contravened s. 18 in the first place, and it was therefore unnecessary to rely on the defence. In line with the primary judge, the High Court held that Google had not contravened s. 18 because they were not the author of the sponsored links. Google Inc. was held to have merely published or displayed them without adopting or endorsing the misleading representations that were made by the advertisers.[19]

Finally, in this context, a few more observations need to be made. As expressed by Stephen J in Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd:[20] “nothing in these terms suggests that a statement made which is literally true … may not at the same time be misleading and deceptive”.[21]

Further, as is made clear through a range of cases, the fact that the true nature of misleading or deceptive conduct could have been revealed through proper inquiries does not mean that such conduct cannot fall within the scope of ACL s. 18. However, on the other hand, CCA s. 137B (4.4.1 below) outlines how the level of damages that may be awarded to compensate the victim of misleading or deceptive conduct can be lowered where the plaintiff has failed to take reasonable care.

Somewhat similarly, in the mentioned case of Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd,[22] Stephen J observed that: “If the consequence is deception, that suffices to make the conduct deceptive”.[23] Thus, there is no requirement in s. 18 that the conduct is intended to be misleading or deceptive, “but if there is an intention to mislead[,] the court may more easily infer that the conduct was in fact misleading”.[24] Put differently, if it can be proven that the defendant intended to mislead and/or deceive, it is easier to show that the conduct was misleading and/or deceptive. However, proof of intention is not an essential element in proving that conduct is misleading and/or deceptive.

- Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Limited (2004) 218 CLR 592, at 615. ↵

- (1972) AR (NSW) 17. ↵

- CRW Pty Limited v Sneddon (1972) AR (NSW) 17, at 32. ↵

- See e.g., Seven Network Ltd v News Interactive Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 1047, at 13. For a discussion of the facts of that case, see: 3.1.3. ↵

- (2013) 249 CLR 435. ↵

- (2020) 145 ACSR 609. ↵

- (1982) 149 CLR 191. ↵

- Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191, at 198. In that case, both the plaintiff and defendant were companies manufacturing furniture. Parkdale (the original defendant) manufactured furniture that was almost identical to that of Puxu (the original plaintiff). Puxu took action against Parkdale for misleading or deceptive conduct. ↵

- Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Ltd (1984) ATPR 40-463. ↵

- [2004] FCA 1047. ↵

- Seven Network Ltd v News Interactive Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 1047, at 14. ↵

- Often courts will cite Knight v Beyond Properties Pty Ltd (2007) 242 ALR 586 [58]. For example, this principle is mentioned in ACCC v Get Qualified Australia Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 2) [2017] FCA 709 [36]-[37]. ↵

- (2015) 330 ALR 67. ↵

- Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne v Powell (2015) 330 ALR 67 [179]. ↵

- [2004] FCA 1047. ↵

- [2011] FCA 1086 (22 September 2011). ↵

- [2012] FCAFC 49. ↵

- (2013) 249 CLR 435. ↵

- Google Inc v ACCC (2013) 249 CLR 435, 442 [3] (per French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ); 461 [75] (per Hayne J); 485 [151] (per Heydon J). ↵

- (1978) 140 CLR 216. ↵

- Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 216, at 227. ↵

- (1978) 140 CLR 216. ↵

- Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 216, at 228. ↵

- see e.g., .au Domain Administration Ltd v Domain Names Australia Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 424, at para 12. ↵