Main Body

4.3 The “Taco test”

Taco Company of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd,[1] involved an Australian company that had operated a Mexican restaurant called Taco Bell’s in Bondi in Sydney since 1977. A chain of Mexican restaurants of the same name had existed in the US for several years. In 1981, the US Company began operating two restaurants called Taco Bell in other parts of Sydney. The Australian company successfully took action under TPA s. 52 and under the tort of passing off.

While aspects of this case have been superseded, the Court in Taco Company of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd,[2] outlined a widely adopted, although not always expressly cited, four-step test of central relevance for the application of TPA s. 52 and thus subsequently for ACL s. 18. We will now examine this text step-by-step.

In the Federal Court of Australia’s July 2020 decision in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Kogan Australia Pty Ltd,[3] Davies J, drew upon the ‘Taco test’ and advanced a seven-step process for applying ACL s. 18 (the ‘Kogan test’). The description below of the application of the four steps of the ‘Taco test’ incorporates references to the approach articulated by Davies J’s ‘Kogan test’.

It is noteworthy, that at least at the time of writing, the seven-step test from Kogan has not since been applied by the Federal Court in subsequent s. 18 decisions.[4]

4.3.1 Step One

Step 1 – “First, it is necessary to identify the relevant section (or sections) of the public (which may be the public at large) by reference to whom the question of whether conduct is, or is likely to be, misleading or deceptive falls to be tested.”[5]

In identifying the relevant section (or sections) of the public, a court will have regard to factors relating to the targeted audience (such as age, gender and special interests), as well as factors relating to the party engaging in the conduct (such as extent of reputation), and factors relating to the object of the conduct (such as price). Handley v Snoid[6] is illustrative in this context. The dispute arose from the fact that two pop groups used virtually identical names, and the case illustrates that the identification of the relevant section can be quite complex:

The evidence establishes that those who are interested in the music which Popular Mechanics plays are mainly young people between the ages of 12 and 30. At least half of them would probably range from ages 12 to 18, that is, would be of school age. There was evidence from a Mr. Righi, the manager of a band booking agency, to the effect that those who attended the major venues mainly in the suburbs were business people, office workers and school students, whilst those who went to the smallest venues in the inner city were apparently more avant-garde young people. At those larger venues at which Popular Mechanics played, some of which held up to 600 and others up to 300, the crowds tended to be mixed in character. I concluded from this evidence that the larger the crowd the more conventional or conservative it was likely to be.[7]

In that case, the Court identified a rather small group of people as the relevant section. In other cases, the courts have found it justified to focus on a much wider section of the public. For example, in Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd,[8] the relevant section of the public was “potential purchasers of a suit of furniture costing about $1,500”.

Step one of the ‘Taco test’ may be superfluous in situations where a particular individual, or small group of individuals, claim to have been misled or deceived. In such a scenario, there is no need to identify the relevant section of the public in the abstract.

This, the first step in the ‘Taco test’ is directly adopted in the ‘Kogan test’ which states: “First, it is necessary to identify the relevant section of the public at which the conduct was directed”.[9]

4.3.2 Step Two

Step 2 – “Second, once the relevant section of the public is established, the matter is to be considered by reference to all who come within it, including the astute and the gullible, the intelligent and the not so intelligent, the well educated as well as the poorly educated, men and women of various ages pursuing a variety of vocations [.]”[10]

The wide test expressed in step 2 of the Taco Bell test has been limited somewhat, for example, by the High Court’s decision in Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Limited.[11] There it was held that a court ought to focus on the “ordinary or reasonable members” of the section identified in step 1, and has the right to disregard “assumptions by persons whose reactions are extreme or fanciful” as controlling the application of TPA s. 52 (ACL s.18). The Court’s reference to ordinary or reasonable members is unfortunate since one can imagine situation where the ordinary members of a group are not necessarily reasonable. In such a situation, the guidance provided in Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Limited is thus insufficient.

Furthermore, more recent cases make clear that, the exact details of what type of person(s) within the relevant group a court will have regard to is somewhat unsettled. In ACCC v Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd,[12] Gray J focused on a “significant body of reasonable consumers”. In contrast, in Seven Network Ltd v News Interactive Pty Ltd,[13] Tamberlin J applied the Nike test more stringently, holding that “The test to be applied is what is the likely reaction to the representation by ordinary or reasonable members of the class to whom the representation is directed … But such a viewer must be presumed to act reasonably”.[14]

In Flexopack SA Plastics Industry v Flexopack Australia Ltd,[15] Beach J outlines some ‘non-contentious principles’ applicable to the case which includes at [261]: ‘[W]here the issue is the effect of conduct on a class of persons (rather than identified individuals to whom a particular misrepresentation has been made or particular conduct directed), the effect of the conduct or representation upon ordinary or reasonable members of that class must be considered.[16] This hypothetical construct avoids using the very ignorant or the very knowledgeable to assess effect or likely effect; it also avoids using those credited with habitual caution or exceptional carelessness; it also avoids considering the assumptions of persons which are extreme or fanciful. Third, the objective characteristics that one attributes to ordinary or reasonable members of the relevant class may differ depending on the medium for communication being considered. There is scope for diversity of response both within the same medium and across different media.’ Justice Beach had used very similar wording to the above in Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne v Powell[17] and again in ACCC v Get Qualified Australia Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 2).[18]

The determination of the characteristics or knowledge attributed to ‘ordinary and reasonable’ members of the relevant class becomes very interesting when representations are made through different media. For example, in Google Inc v ACCC[19] the High Court upholds the primary judge’s reasoning, undisturbed in the Full Court appeal, that the relevant class consist of people who have access to a computer and have some basic knowledge and understanding of computers, the web and search engines such as Google. The primary judge stated that ‘[i]t is not possible to use a search engine in any meaningful way without knowing something about how it operates.’[20]

In addition, there is interesting discussion by Colvin J in ACCC v Geowash Pty Ltd (Subject to a Deed of Co Arrangement) (No 3)[21] at [623] where his Honour states: ‘If the audience for the conduct in issue comprises the less educated, the gullible or those prone to misconceptions then a determination as to whether the conduct is misleading or deceptive is to be undertaken in that context. The legislation does not afford protection for a member of the audience who responds unreasonably, but unreasonableness is to be evaluated having regard to the characteristics of the audience members in the particular case.’

At any rate, Finkelstein J has expressed the view that, in the light of Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Limited,[22] there is no need to establish that a significant number of members of the identified section would be misled or deceived, and has further stated that:

How then is one to identify and give characteristics to Campomar Sociedad’s hypothetical individual? Logic demands that if one is dealing with a diverse group then, for the purpose of determining whether particular conduct has the capacity to mislead, it is necessary to select a hypothetical individual from that section of the group which is most likely to be misled. If the court is satisfied that this hypothetical individual is likely to have been misled by that conduct, that would be sufficient.[23]

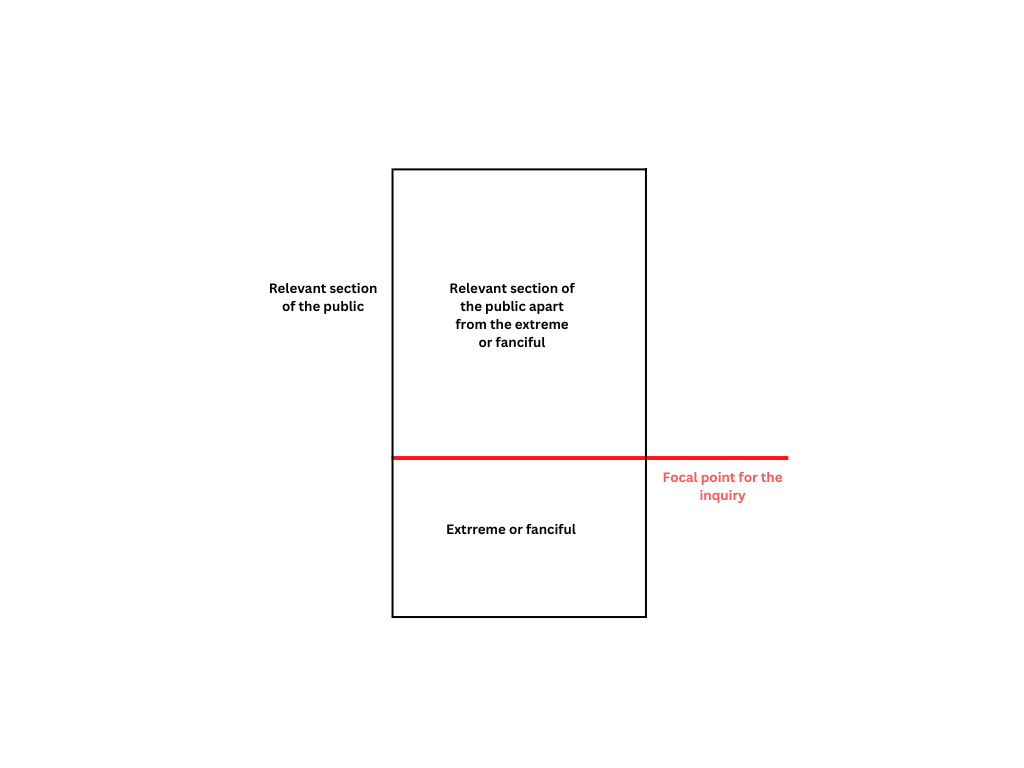

This latter approach rests on a logical foundation and represents the preferable option. At the same time, however, this should not be read as detracting from the limitations imposed by the High Court in Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Limited.[24] Combining the High Court’s judgment in Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Limited[25] with Finkelstein J’s logical reasoning in .au Domain Administration Ltd v Domain Names Australia Pty Ltd,[26] the following Rule can be formulated:

Rule 6

Once the court has established the relevant section of the public, the matter of whether the conduct in question is misleading or deceptive is to be considered by reference to whether a hypothetical individual from that group of the relevant section which is most likely to be misled, yet whose reactions to the relevant conduct are not extreme or fanciful, would be misled or deceived.

Expressed as a diagram, the proper focal point can be illustrated as follows:

This approach is similar to that of Franki J’s in Taco Company of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd: “all persons exposed to the conduct should be considered although conduct which is only likely to mislead or deceive an extraordinarily stupid person would not fall within sec 52 [ACL s. 18]”.[27]

Like step one, step two of the ‘Taco test’ may be superfluous in situations where a particular individual, or small group of individuals, claim to have been misled or deceived. In such a scenario, a court may instead pay attention to the characteristics of the relevant individuals, such as their experience and knowledge, and familiarity with the type of subject matter of the dispute. For example, in Green v AMP Life Limited,[28] Mr Green was a financial planner and an agent selling insurance policies underwritten by AMP Life Ltd. He was a member of the Australasian Association of AMP Society Agents. In 1997, an arrangement was created known as the Income and Agency Protection Plan. The purpose of the plan was to provide income protection for agents in the event of disability. Pursuant to the plan, members of the Australasian Association of AMP Society Agents could, by making application to AMP Life Ltd, become entitled to receipt of benefits under the policy. In 2001, Green was diagnosed as suffering from a mental illness. AMP Life Ltd accepted his claim under the policy, however, it ceased to pay benefits to him after two years. The primary issue that arose was whether Green’s entitlement to the benefit ended after two years, or was on-going. Having gone some way to emphasise the need to focus on the characteristics of the relevant individual, the Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal.

The ‘Kogan test’ articulated by Davies J, breaks what is step two of the ‘Taco test’ into five separate steps that also link into the discussion above (see discussion above at 4.1.3) as to how we define what conduct amounts to being misleading or deceptive:

Secondly, it is necessary to consider who comes within that target audience …

Thirdly, the Court considers the natural and ordinary meaning conveyed by the representations by applying an objective test of what the ordinary or reasonable consumers in the class would have understood as the meaning in light of the relevant contextual facts and circumstances … This will, or may, include consideration of the type of market, the manner in which the goods are sold, and habits and characteristics of purchasers in such a market … In advertising material, where simple phrases and notions may evoke attractive notions without precise meaning, context and the “dominant message” are important …

Fourthly, whether conduct is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive is to be tested by whether a hypothetical ordinary or reasonable member of the target audience is likely to be misled or deceived, excluding reactions that are extreme or fanciful … The issue is not whether the impugned conduct simply causes confusion or wonderment … Conduct is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive if it has the tendency to lead into error, requiring a causal link between the conduct and the error on the part of the person to whom the conduct is directed. The law is not intended to protect people who fail to take reasonable care to protect their own interests … Further, there is no need to demonstrate any intention to mislead or deceive – conduct may be misleading and deceptive even where a person acts reasonably and honestly …

Fifthly, whether the hypothetical member of the target audience is likely to be misled or deceived may involve questions as to the knowledge properly to be attributed to the members of the target audience … It is also necessary to isolate by some criterion a hypothetical representative member of the class …

Sixthly, within the target audience, the inquiry is whether a “not insignificant” portion of the people within the class have been misled or deceived or are likely to have been misled or deceived by the relevant conduct, whether in fact or by inference …[29]

It is noteworthy that Davies J’s ‘Kogan test’ in its step five merely concludes that “[i]t is also necessary to isolate by some criterion a hypothetical representative member of the class” (emphasis added) without attempting to define such as criterion. Arguably, more could also have been said about the link between the search for a hypothetical representative member of the class in step five and the conclusion in step six that the inquiry is whether a “not insignificant” portion of the people within the class have been misled or deceived or are likely to have been misled or deceived.

There seems to be quite a lot of confusion around whether it is necessary to prove a ‘not insignificant’ portion of persons in the relevant class had been misled or deceived or were likely to be misled or deceived. Although there is this discussion in Kogan (in step 6 above), a Full Federal Court decision in ACCC v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (‘TPG’)[30] that followed Kogan held the requirement to be ‘at best, superfluous to the principles stated by the High Court in Puxu, Campomar, and Google Inc and, at worst, an erroneous gloss on the statutory provision.’[31]

The Court held that nothing in the language of the statute requires courts to determine the size of any proportion. The Court also notes that it is open for parties to seek to establish that conduct is misleading by establishing that persons were in fact misled, and in those circumstances, it may be necessary to prove that the number of such persons were significant in order to persuade the court that the conduct is in fact misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive but ‘it is not a requirement inherent in the statute’.[32]

The Full Court in TPG outlines some history of the ‘significant number’ test. It had first been doubted by Finkelstein J in ASIC v National Exchange Pty Ltd[33] and in .au Domain Administration v Domain Names Australia Pty Ltd.[34] However, the Full Court in National Exchange concluded that the ‘significant number test’ was merely another way of expressing the test in Campomar. This view was also taken by Beach J in Flexopack SA Plastics Industry v Flexopack Australia Pty Ltd,[35] where his Honour stated that if the Campomar test is satisfied, then such a finding carries with it a finding that a significant portion of the relevant class would be likely to be misled. However, Beach J then determined in ACCC v Get Qualified Australia Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 2)[36] that finding that reasonable members of the class would be likely to be misled does not necessarily carry with it a finding that a significant portion of the class would be likely to be misled therefore the ‘significant number’ test is an additional requirement to be satisfied.

4.3.3 Step Three

Step 3 – “Thirdly, evidence that some person has in fact formed an erroneous conclusion is admissible and may be persuasive but is not essential. Such evidence does not itself conclusively establish that conduct is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive. The Court must determine that question for itself. The test is objective.”[37]

The types of conduct that may constitute “misleading or deceptive” conduct have been discussed above (4.1.3). It should, however, be stressed that one important consequence of the court applying an objective test is that there is no requirement that somebody was in fact misled or deceived. Further, there is no need to show that actual damages are suffered from the misleading or deceptive conduct.

As Step 3 makes clear, the fact that the test is an objective one also means that evidence that someone has in fact been misled does not in itself establish that the conduct in question was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive.

Finally, a court may evaluate the relevant conduct from several angles. For example, in Seven Network Ltd v News Interactive Pty Ltd,[38] Tamberlin J first evaluated whether each component of the defendant’s conduct could be regarded as misleading or deceptive. The learned judge examined whether “when taken together … the cumulative impact of all these elements creates the impression in the mind of a reasonable visitor of a kind that can be said to be one of the types of association covered by [TPA] s. 52 [ACL s. 18] and [TPA] s. 53(c) and (d) [ACL s. 29 (g) and (h)] of the Act”.

The ‘Kogan test’ articulated by Davies J adopts the same approach outlined here:

Seventhly, evidence that someone was actually misled or deceived by an advertisement is not required … In circumstances where the advertisements were directed to the public at large the absence of such evidence is not of great significance … Correlatively, evidence that a person has been misled by an advertisement is not conclusive that its publication constitutes misleading or deceptive conduct.[39]

4.3.4 Step Four

Step 4 – “Finally, it is necessary to inquire why proven misconception has arisen … The fundamental importance of this principle is that it is only by this investigation that the evidence of those who are shown to have been led into error can be evaluated and it can be determined whether they are confused because of misleading or deceptive conduct on the part of the respondent.”[40]

This, the fourth and last step, originates in Hornsby Building Information Centre v Sydney Building Information Centre,[41] and is only of relevance in relation to situations where it has been proven that somebody has, in fact, been misled or deceived. It involves the evaluation of whether persons misled or deceived were misled or deceived due to the defendant’s conduct, or due to other factors. To use the words of Finkelstein J in .au Domain Administration Ltd v Domain Names Australia Pty Ltd:[42] “there must be a ‘sufficient nexus’ between the conduct and the error or misconception”.

In Hornsby Building Information Centre v Sydney Building Information Centre,[43] Hornsby Building Information Centre was appealing an injunction granted against them precluding them from using their name, as doing so was said to constitute a breach of TPA s. 52 (ACL s. 18). The High Court held that no such breach had taken place, as any confusion in the minds of the public was due to the fact that Sydney Building Information Centre had operated as the only Building Information Centre in the area for such a long time:

Any deception which does arise stems not so much from the Hornsby Centre’s use of the descriptive words as from the fact that the Sydney Centre initially chose descriptive words as its title and for many years thereafter was the only centre in Sydney which answered the description which those words provide. In consequence members of the public have come to associate its particular business with that type of activity. Evidence of confusion in the minds of members of the public is not evidence that the use of the Hornsby Centre’s name is itself misleading or deceptive but rather that its intrusion into the field originally occupied exclusively by the Sydney Centre has, naturally enough, caused a degree of confusion in the public mind. This is not, however, anything at which [TPA] s. 52 (1) [ACL s. 18] is directed.[44]

Consequently, in that case, the errors people made did not stem from misleading or deceptive conduct. This again highlights how the fact that people have been led into error is not conclusive evidence of the conduct in question being misleading or deceptive.

A fictional example may provide further illustration of the operation of step four. Imagine that you visit a shop you have visited many times before. Without looking carefully, you purchase a jumper assuming it to be of a particular brand as the shop, as you know it, sells only products of that brand. Imagine further that it turns out that the jumper is not of the brand you thought it would be as the shop has changed ownership and therefore also changed the type of products it stocks.

In such a case you may have been misled into buying the ‘wrong’ brand of jumper. However, your error in the example would typically be due to your own preconceptions, not due to any particular conduct of the seller. In such a case, step four is likely to protect the seller.

Finally, as noted above, Kogan states that ‘[t]he law is not intended to protect people who fail to take reasonable care to protect their own interests …’ This principle was recently applied in ACCC v Employsure Pty Ltd[45] however referencing Puxu. Based on this reasoning, the Court found that ordinary and reasonable members of the class would not have been misled or deceived or likely to have been misled or deceived because if they were wanting to contact the Fair Work Ombudsman or Fair Work Commission, they would have verified that they were calling the correct number and taken more reasonable care in doing so.

- (1982) ATPR 40-303. ↵

- (1982) ATPR 40-303. ↵

- [2020] FCA 1004. ↵

- See e.g., ACCC v Employsure Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1409; Telstra Corporation v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1372; TPG v ACCC (2020) 384 ALR 496; ACCC v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2020) 381 ALR 507 (note the final two listed cases are Full Federal Court decisions.). ↵

- (1982) 42 ALR 177, 202. ↵

- (1981) ATPR 40-219. ↵

- Handley v Snoid (1981) ATPR 40-219, 42-975. ↵

- (1982) 149 CLR 191, at 199. ↵

- Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Kogan Australia Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1004 [10]. ↵

- (1982) 42 ALR 177, 202. ↵

- (2000) 202 CLR 45. ↵

- [2004] FCA 516. ↵

- [2004] FCA 1047. ↵

- Seven Network Ltd v News Interactive Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 1047, at para 13. ↵

- (2016) 118 IPR 239. ↵

- Citing Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Limited (2000) 202 CLR 45 [102]-[103]. ↵

- (2015) 330 ALR 67. ↵

- [2017] FCA 709. ↵

- (2013) 249 CLR 435. ↵

- See ACCC v Trading Post Australia Pty Ltd (2011) 197 FCR 498 [122]. ↵

- (2019) 368 ALR 441. ↵

- (2000) 202 CLR 45. ↵

- .au Domain Administration Ltd v Domain Names Australia Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 424, at para 21. ↵

- (2000) 202 CLR 45. ↵

- (2000) 202 CLR 45. ↵

- [2004] FCA 424. ↵

- (1982) ATPR 40-303, at 43-752. ↵

- (2005) ASAL 55-147. ↵

- Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Kogan Australia Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1004, [11]-[15]. ↵

- (2020) 381 ALR 507. ↵

- See ACCC v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2020) 381 ALR 507 [23]. ↵

- See ACCC v TPG Internet (2020) 381 ALR 507 [23](g). ↵

- (2003) 202 ALR 24. ↵

- (2004) 207 ALR 521. ↵

- (2016) 118 IPR 239. ↵

- [2017] FCA 709. ↵

- (1982) 42 ALR 177, 202. ↵

- [2004] FCA 1047, at 31. ↵

- Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Kogan Australia Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1004, [16]. ↵

- (1982) 42 ALR 177, 203. ↵

- (1978) 140 CLR 216. ↵

- [2004] FCA 424, at 12. ↵

- (1978) 140 CLR 216. ↵

- Hornsby Building Information Centre v Sydney Building Information Centre (1978) 140 CLR 216, at 230. ↵

- [2020] FCA 1409. ↵