Searching

Learning Objectives

This chapter will help you:

- understand the overall search process for a review.

- decide how you will document your search strategy.

- decide where to search.

“Systematically searching the literature ensures that you identify relevant studies for your review question. The breadth and type of approach you take will depend on the type and topic area of your review” (Booth et al., 2022, p. 153).

Systematic searching

The aim of searching for a systematic or scoping review is to find all available evidence that may be relevant to your question. You need to balance finding all available evidence (sensitivity) with reducing the number of irrelevant results (specificity). In a review, you need to perform a very sensitive search so relevant evidence is not missed to reduce the risk of bias and ensure reliable results. All searches in reviews need to be reproducible for transparency. This may result in thousands of articles being retrieved which will be screened according to the inclusion criteria set in the protocol.

Methodological guidance recommends consulting an experienced librarian when developing your search strategy (Lefebvre et al., 2024; Ross-White et al., 2024). This is because librarian involvement in review teams as consultants or authors results in higher quality and more comprehensive reporting of search strategies (Pawliuk et al., 2024; Rethlefsen et al., 2015; Schellinger et al., 2021).

Three steps to searching

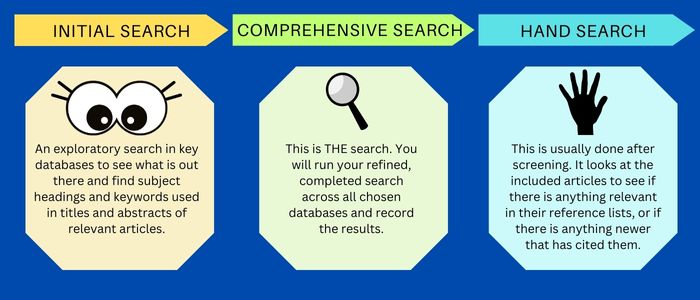

JBI recommends a three-step process when searching the literature for a review (Peters et al., 2020). For scoping reviews, it is acceptable to adapt and alter the search as needed, documenting any changes made. For systematic reviews the search is not altered from the search strategy documented in the protocol.

Documentation

Before you begin, consider how you will document your search. This is vital when you report the review. Systematic searching takes many hours of hard work with trial and error as you refine your searches. Documentation will:

- record decisions made of why some terms are included or excluded with justifications,

- save time because you know where you are up to and don’t waste time repeating work,

- increase the transparency of the search process and the accuracy of results, and

- enable the search to be reproduced e.g., when updating results closer to publication (Monash University Library, 2022).

Start from the moment you begin developing your search strategy, making it easy to edit and change as you develop the initial search. How you do this is a personal preference. Some people like to use a table, a document, or a spreadsheet.

Details you can document include:

- the date each search was performed

- the keywords and subject headings

- explanations of keywords and subject headings tried out in development but not used in the final search

- any filters or limiters:

- date range

- population or age range

- type of publication e.g., peer-reviewed journal article

- study type e.g., randomised control trials

- language

- the names of databases and platforms used eg. MEDLINE database on the EBSCOhost platform

- the number of results for each term and combination of terms

- the number of results for each database after the removal of duplicates

- a list of seed papers that must be included in the results

- if results were exported to reference management software (Monash University Library, 2022; University of Manitoba Libraries, 2023).

Keep in mind you will need to report your search strategy and process in the methods section of your review. PRISMA-S guides authors on the search elements that should be reported on and can help you decide what you should document (Rethlefsen et al., 2021).

Choosing where to search

Planning where to search is important, as various sources offer different types of material and discipline coverage, and making careful selections helps ensure you have found all available evidence and reduces possible bias in your review (Fowler & Jewell, 2022).

Databases

Search a range of databases as no single one covers all the literature. It is not acceptable to only search one.

The databases you select depend on your research question and discipline. Most reviews search primary databases, which include published articles and original research. Some are discipline specific, such as CINAHL for nursing, while other indexing platforms such as Scopus and Web of Science are multidisciplinary. You may also need to search in secondary databases which include systematic reviews and other evidence-based material, such as the Cochrane Library.

Grey literature

Grey literature is information published by governments, academics, business, or industry that is not driven by commercial publication. Resources of sufficient quality, such as theses, pre-prints, reports, research registers, clinical trial reports, or conference proceedings may be held in repositories or libraries.

The benefits of including grey literature include:

- faster publishing than traditional peer-reviewed articles

- the inclusion of statistics

- it is more openly accessible

- filling in the gaps of traditional publishing formats

- more localised information

Example

The following is an example of the databases and concepts searched in a published systematic review.

Sullivan, O., Curtin, M., Flynn, R., Cronin, C., Mahony, J. O., & Trujillo, J. (2024). Telehealth interventions for transition to self-management in adolescents with allergic conditions: A systematic review. Allergy, 79, 861-883. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.15963

Further reading

Paez A. (2017). Gray literature: An important resource in systematic reviews. Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine, 10(3), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12266

References

Booth, A., Sutton, A., Clowes, M., & Martyn-St James, M. (2022). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Fowler, S. A., & Jewell, S. T. (2022). Database searching. In S. T. Jewell, & M. J. Foster (Eds.), Piecing together systematic reviews and other evidence syntheses (pp. 93-110). Rowman & Littlefield.

Lefebvre, C., Glanville, J., Briscoe, S., Featherstone, R., Littlewood, A., Metzendorf, M-I, Noel-Storr, A., Paynter, R., Rader, T., Thomas, J., & Wieland, L. S. (2024). Searching for and selecting studies. In J. P. T. Higgins, J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M. J. Page, & V. A. Welch (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (version 6.5). Cochrane. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-04

Monash University Library. (2022). Document your search. Systematic searching for a review. https://rise.articulate.com/share/Hlqvovc-81cls7F5kRAXM3JYSoitcJYd#/lessons/EgR6rBrKjj7YUJ_JbddUzw7IhKSS3xu9

Pawliuk, C., Cheng, S., Zheng, A., & Siden, H. (2024). Librarian involvement in systematic reviews was associated with higher quality of reported search methods: A cross-sectional survey. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 166. Article 111237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2023.111237

Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A. C., & Khalil, H. (2020). Scoping reviews. In E. Aromataris, & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI manual for evidence synthesis. https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/355862497/10.+Scoping+reviews

Rethlefsen, M. L., Farrell, A. M., Osterhaus Trzasko, L. C., & Brigham, T. J. (2015). Librarian co-authors correlated with higher quality reported search strategies in general internal medicine systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 68(6), 617-626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.11.025

Rethlefsen, M. L., Kirtley, S., Waffenschmidt, S., Ayala, A. P., Moher, D., Page, M. J., Koffel, J. B., & PRISMA-S Group. (2021). PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA Statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10, Article 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01542-z

Ross-White, A., Lieggi, M., Palacio, F. G. L., Solomons, T., Swab, M., Rothfus, M., Takahashi, J., & Cardoso, D. (2024). Search methodology for JBI evidence syntheses. In E. Aromataris, C. Lockwood, K. Porritt, B. Pilla, & Z. Jordan (Eds.), JBI manual for evidence synthesis. https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/355827873/2.4+Search+Methodology+for+JBI+Evidence+Syntheses

Schellinger, J., Sewell, K., Bloss, J. E., Ebron, T., & Forbes, C. (2021). The effect of librarian involvement on the quality of systematic reviews in dental medicine. PLoS One, 16(9), Article e0256833. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256833

University of Manitoba Libraries. (2023). Setting up a systematic review search. Part 2: Setting up a search. https://libguides.lib.umanitoba.ca/RFHS-KSsupport/Series-Part2

The available facts or information

The risk of a systematic error in the research that could detract from the truth.

The process of checking the eligibility of studies found in the search

Qualifications and disqualifications for retrieved results.

A word or phrase that describes all material in a database on that subject.

A systematically organised collection of information, such as journal articles.

A company which provides access to a number of databases through the same interface.

A group of known articles about a topic that are used to start developing a search, or test a search.

A program that helps create and manage records of literature.

A database of a learning institution such as a university where material produced as part of their research is archived.