Chapter 9 – Monitor Progress, Learn and Adapt

Learning Goals

Use these learning goals to focus your attention, connect new ideas to your own context, and identify practical ways to apply what you learn. In this chapter you can:

- Integrate project management principles

- Monitor progress

- Support learning and adaptation.

Prepare the Plan

This is the second of two chapters that bring together behavioural insights, implementation strategies, and an understanding of organisational context into an actionable implementation plan.

The focus of this chapter is to translate the visual map of implementation strategies within the logic model into a practical plan, ready for implementation.

Apply Project Management to Implementation

Project management is often seen as a technical discipline, but its principles are valuable in guiding complex change. Key practical strategies can help to shift behaviours and organisational cultures by organising people and resources to achieve a shared goal within a defined timeframe. In implementation, it provides the structure needed to translate a logic model into practical action.

The table below describes common project tasks and situates them within the implementation planning activities.

Project Task |

Key Questions |

Implementation Activities |

|

Initiation |

What do we want to achieve? Why is it important? |

Clarify the important problem

|

|

Planning |

Who needs to be involved? What needs to happen? |

Identify and engage key stakeholders Evaluate organisational context |

|

Design & analysis |

What are the key activities? How will they work together? |

Select & co-design implementation strategies Clarify feasible outcomes in a logic model |

|

Execution |

How will we deliver? What risks need managing? |

Translate strategies into tasks & roles Coordinate implementation activities |

|

Monitoring |

Are we on track? What needs to change? |

Review progress towards outcomes Gather feedback and make adaptations |

|

Consolidation |

What did we learn? What will be sustained? |

Reflect and summarise learnings Spread and scale sustainably |

In busy and complex health systems, changes happen when roles are clear, support structures are in place, and change processes are embedded in the broader governance of the organisation. To achieve this, careful consideration of team structures, leadership roles, and governance arrangements is recommended.

Formalise an implementation team

From key stakeholders, clarify who has the authority to allocate resources and make decisions. Determine the need for and continuation of advisory and working groups.

Confirm roles and responsibilities for a core implementation team that will deliver on the implementation strategies. Ensure that individuals within the team have the operational authority, content knowledge and leadership capabilities to enact the proposed change. Identify and match people to key roles. Translate the shared purpose into guiding principles for implementing the change.

Clarify leadership roles

Change efforts often falter because leadership is assumed rather than defined. A robust implementation effort will have multiple leadership roles, each with a distinct purpose. Multiple implementers also bring a diverse understanding of the health system to the team. When they work together, they can avoid system bottlenecks and create new connections and patterns of communication.

A senior leader or sponsor provides formal authority, visibility and resources. They have a key role in aligning resources to enable behaviour change and the use of implementation strategies. Depending on the size of the organisation and the intended change, senior leaders may be part of, or the reporting line for, implementation teams.

Operational implementation leaders are required to track and coordinate progress and resolve practical issues. They allocate implementation strategies into discrete tasks and determine who will lead each activity, with appropriate resources. Simple timeline planners, action logs and responsibility matrices can highlight key tasks. Tools like Gantt charts can also be helpful.

Champions can be either formal or informal leaders who believe in the change. They understand the evidence and can visualise the required changes in practice. Through their social and professional networks, they model new behaviours and mentor individuals in practical and regular interactions. As implementation starts to take shape, momentum and morale become important, and achievements need to be recognised and framed as making progress towards the larger benefit.

Embed facilitation

As planning transitions into implementation, a dynamic and relational approach becomes essential. Facilitation is both a task and a mindset that all members of the implementation team can adopt. It represents a collaborative leadership practice that empowers people to reflect, connect, and act with purpose. Through supportive strategies like coaching, sensemaking, and shared problem-solving, facilitation helps teams navigate complexity and make meaningful progress together.

Facilitators are not limited by title and may be internal or external to the implementation team. They ask questions to clarify, listen without judgment and reframe challenges as learning opportunities. They enable space to discuss and reflect before moving forward. Facilitating is key to individuals engaging with and committing to sustain improvements.

Situate change within organisational governance

Clear reporting and accountability structures ensure that implementation is prioritised and supported. Embedding an implementation plan into existing governance structures gives it visibility and legitimacy. Consider integration into relevant working documents and processes, such as business cases for change, workforce development plans or operational planning processes. Building new routines into existing team structures reduces the overall burden and increases ownership, so that, over time, they become part of the workplace culture.

To do this, ensure the sponsor is situated within key committees or executive groups to both advocate for and oversee implementation. Identify suitable reporting and communication mechanisms to support this. Where possible, link implementation progress to key quality and safety agendas, or service performance priorities. Clarify how the proposed benefits will address the original challenging problem.

Data management is an important function to monitor progress and evaluate outcomes. Data can be a powerful lever for change when it is routinely collected in a meaningful and timely format. Data can also help to explain change through documenting trends and linking explanations to user experiences.

Risk mitigation and management is also important for the longevity of change. Ideally, leaders will have sufficient autonomy to make informed adaptations in response to inherent changes within the healthcare system.

Monitor progress

The healthcare system’s propensity for change makes monitoring progress vital for successful implementation. Healthcare organisations are often subject to shifting priorities, workforce changes, resource pressures and unexpected barriers. Despite every effort to anticipate and prepare, no plan can anticipate everything.

Seek feedback

In complex systems, feedback is a powerful tool, when it is timely and meaningful. When implementation leaders acknowledge their uncertainty and engage those who provided feedback, they can facilitate genuine conversations. Not every deviation from the plan is a threat. Some are insights. The challenge for implementers is to be able to adapt intentionally to achieve the desired outcomes.

Design progressive data collection to monitor and provide feedback as to whether implementation strategies are being delivered as intended. Look for what is working as intended, and where things are off track or facing resistance. Integrate frequent and low-burden feedback loops, such as regular and quick check-ins, review points, and introduce simple audit tools. Collect and connect both quantitative (counts, percentages) and qualitative (stories, observations) data to understand what is really happening. Ensure progress is reviewed honestly, without blame, and focused on learning.

Support learning and adaptation

Learning cultures are characterised by teams that use data and experience to continuously improve their practice. When people are connected across traditional silos, and there is time and space to reflect, monitoring is the focus for learning and appropriate adaptations can be made.

Facilitating progress is key to maintaining momentum, and a core source of learning. Successful implementation teams plan to adapt, rather than expecting the plan to work exactly as written. When leaders build reflective practices into the team culture, through regular debriefing and learning logs, they encourage shared sensemaking. They can create psychological safety so that people are confident to raise concerns, knowing that discussion and reflection is routine. This can be accentuated when facilitators and leaders model curiosity and humility.

Make appropriate adaptations

When modifications are required, aim to maintain fidelity by respecting the core purpose and mechanisms of the implementation strategies.

Adaptationin implementation refers to the process of intentionally modifying an evidence-based intervention, innovation or implementation strategy to improve its fit or function, in relation to local needs, resources and context. The goal is to maintain fidelity to the core components that are critical for an effective outcome. When adjustments are made during implementation in response to challenges or feedback, these adaptations ensure the progress of change. The following table provides examples of key forms of adaptation in relation to using educational strategies.

Type of Adaptation |

Description |

Examples |

|

Intervention Adaptation |

Involves modifying content, materials, or delivery of the original evidence-based intervention or innovation. |

Modify content to respect cultural norms Alter the format or frequency of sessions to fit local resources and patient needs |

|

Implementation Strategy Adaptation |

Entails changing the way implementation strategies are introduced or integrated into practice in response to feedback during implementation. |

Provide more detailed orientation for users to improve adoption Provide digital access to sessions to enhance uptake Support clinical champions to introduce simulation labs to enable safe practice |

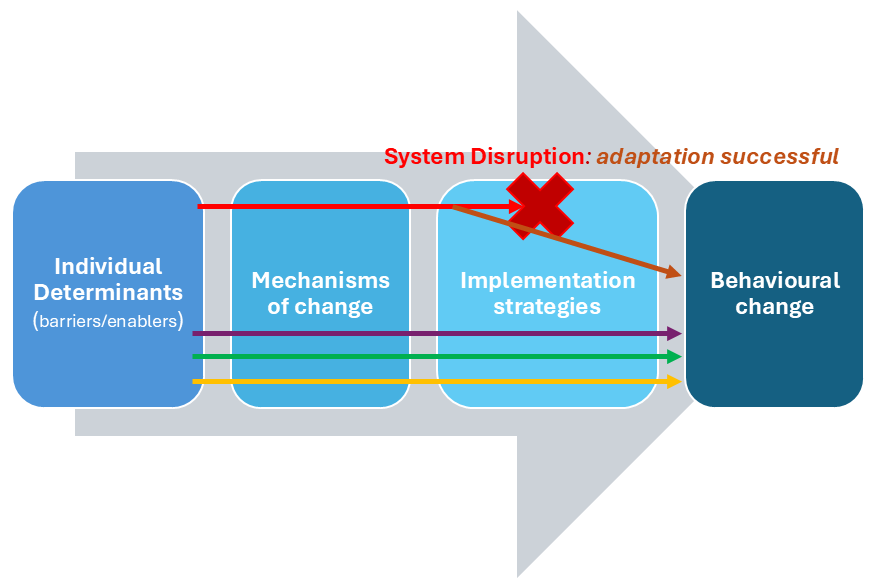

Although complex systems are often unpredictable, change can be guided using simple rules or theoretical explanations, as exemplified in the choice of implementation strategies. Behaviour theory explains how barriers are addressed (or enablers leveraged) to empower a key mechanism of change underpinning a specific implementation strategy. When implementation strategies are measured regularly, patterns can be observed that reflect this explanation. However, when the system is disrupted and something unexpected occurs, this can stimulate a process of learning.

Theoretically similar implementation strategies that are more suitable to the setting can be introduced to empower the same underlying mechanisms of change. This is often how adaptations are created to maintain the original momentum of change. This process of learning and adaptation is summarised in the figure below, where the coloured lines represent theoretically informed implementation strategies that underpin specific behaviour changes.

In this diagram, regular monitoring identified that system disruptions prevented the top red implementation strategy from supporting the behaviour change. For example, in the staff wellbeing implementation project, one of the wellbeing champions had to take unexpected extended leave, and the workflow redesign project he was leading was at risk of stalling. A quick adaptation in the form of the new brown implementation strategy enabled support for the behaviour change. A temporary wellbeing champion was able to adjust the timelines and activities in the workflow redesign to enable its successful completion. There was a short period of handover between the two well-being champions.

Successful implementation relies on motivated people crafting relevant implementation strategies and monitoring schedules so problems can be addressed as they arise in real-time.

Adaptation ensures that implementation strategies continue to be adopted over time. This offers a systematic way to adjust strategies across diverse and dynamic healthcare environments. A nuanced understanding of adapting implementation strategies to the practical conditions is important for sustaining change, and for spreading a similar change to other settings. This will be developed further in the next chapter.

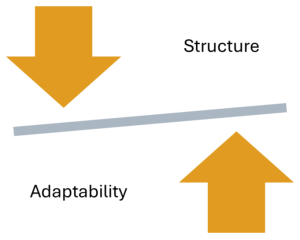

Navigate the Paradox Between Structure and Adaptability

The transition from planning to implementation requires structure. Implementation teams need clearly defined roles, aligned resources, and visible governance so that individuals feel supported to act and learn together.

Implementation plans also need to be adaptable. In complex systems, implementation teams need the freedom to adjust activities and timelines, to respond to emerging needs, and to honour the local wisdom.

Implementation plans also need to be adaptable. In complex systems, implementation teams need the freedom to adjust activities and timelines, to respond to emerging needs, and to honour the local wisdom.

This implementation paradox represents the tension between a structure that enables coordination and accountability, while being flexible enough to navigate what emerges in busy healthcare organisations.

Power lies in the teams’ ability to appropriately adapt and continue to learn as the plan unfolds.

Progress happens when teams are given enough structure to move forward and enough flexibility to adapt as they need to.

Case Scenario: “The Dashboard Was Green—But That Was Not The Whole Story”

Setting:

A regional university that provides undergraduate education for a wide range of health professions. All programs incorporate early student interactions with patients, peers and actors to increase their familiarity with communicating with patients before students spend time in clinical settings.

Challenge:

With growing numbers of health professional students, and health workforce shortages, professional programs are struggling to provide students with opportunities to practice and improve their skills and confidence in communicating with patients.

Opportunity:

A simulation platform that uses generative AI to play the role of patients was introduced in one professional program to determine if it could be used to supplement existing tools. There was some emerging research of the platform’s ability to support professional learning and several exemplar reports of benefits from its use in other universities.

Initial Action:

A business case for change was supported within the health faculty of the university. An academic advisory group embedded the simulation platform into a specific teaching module and adapted the virtual patient profiles, to complement the existing curriculum. An implementation plan was developed to include the use of embedded digital feedback surveys.

Halfway through the semester, there was no student feedback to review. The digital dashboard showed that a high proportion of students had initially logged in, but their use of the platform was inconsistent.

Emerging Tension:

This scenario exemplified the Structure vs. Adaptability paradox.

The simulation platform was designed to fit into the academic modular structure, and students were encouraged to make use of this new opportunity to practice their communication skills. The implementation team had focussed on fitting the simulation platform into the academic program with minimal disruption.

However, with no feedback, they could not understand what the students were experiencing.

Turning Point:

Student discussion groups were created to seek feedback about their experiences. An informal student champion organised these groups on different campuses and led the discussion. There were a range of technical challenges, misunderstandings about the purpose and privacy of the simulation platform and some students were spreading negative perceptions about the way the virtual patients looked and talked.

All of this feedback was valuable to the implementers, who received it with curiousity, and asked clarifying questions to get to some of the core issues. They realised and students confirmed that the digital feedback system did not seem an appropriate way to share these issues.

Student champions were empowered to gather feedback from their peers and meet with implementers regularly to progressively trial adaptations.

Reflection Questions

- Have you relied on data that didn’t reflect what people were experiencing?

- How have you realised the need to make adaptations as you implemented a change?

Key Takeaways

1. Project structures create clarity, enable coordination and support alignment.

Planning is realised when everyone understands the goals, responsibilities and timelines.

2. Adaptability ensures responsiveness to system complexity and human dynamics.

Implementation is a dynamic process, and plans must be responsive to real world challenges. New insights emerge from regular monitoring and feedback and form the basis for practical adaptations.

3. Facilitative leaders can create conditions for people to learn and respond.

With time and space to reflect on progress and feedback, the implementation plan can become a learning tool, helping teams to make relevant adaptations.

Additional Resources & Templates

Understanding change in healthcare systems.

- In a recent study of 7 health services in Australia, empirical data are synthesized with the literature to build a profile of four key system enablers. This complex paper provides theoretical and practical examples of implementing change within large and complex healthcare systems.

Understanding Facilitation

- For a personal exploration of the process of becoming a facilitator, and the different domains of facilitation practice, this blog post is insightful.

Understanding adaptation in implementation

- This blog post offers a practical summary of using adaptations.

Available Templates

Access the templates on the author’s From Research to Reality webpage on the Mosaic website:

- Apply Project Management to Implementation

- Making Adaptations during Implementation

The application of knowledge, tools, and techniques to plan, execute, and complete a defined project within scope, time, and budget.

A relational and strategic process that empowers and enables individuals and teams to adopt new practices by guiding, supporting, and building capacity within a specific context.

Systematic collection and rigorous analysis of data within clear accountabilities and security, for monitoring, reporting and evaluation purposes.

In implementation it refers to the process of intentionally modifying an evidence-based intervention, program, or implementation strategy to improve its fit or function, in relation to local needs, resources and context.