Chapter 5 – Map the System and Organisation

Learning Goals

Use these learning goals to focus your attention, connect new ideas to your own context, and identify practical ways to apply what you learn. In this chapter you can:

- Identify healthcare and organisational systems

- Map a specific organisational system

- Evaluate organisational readiness

Assess the Situation

Welcome to the second of two chapters designed to assess the situation at the core of your implementation plan.

Welcome to the second of two chapters designed to assess the situation at the core of your implementation plan.

The focus of this chapter is to understand the environment in which implementation will occur.

Every health system, service, and team operates within a web of structures, relationships, workflows, and priorities that shape what is possible. Mapping this system, carefully and deliberately, enables new ideas and research evidence to be implemented judiciously for meaningful change.

Identify Healthcare and Organisational Systems

It is useful to conceptualise broad national healthcare systems as ecosystems that include a diverse range of elements that all interact with one another. Understanding how these elements shape organisational priorities and influence change is essential for planning implementation.

Across most countries, healthcare services are shaped by a set of common drivers that influence priorities, policies, and performance. These include a focus on quality and safety, equitable access, and cost-efficiency, alongside the need to support a sustainable and capable workforce. Healthcare systems are also guided by regulatory compliance, patient-centred care, and data-informed decision-making. National strategies and priorities can also shape these healthcare ecosystems. For example, goals to improve population health outcomes and promote integration across care settings influence the way healthcare services are delivered. These priorities create both pressures and opportunities for change, and understanding them is essential when planning to implement change within healthcare organisations.

Organisational systems

Within national health ecosystems, many separate organisations work together, including public health agencies and hospitals, regulatory and professional organisations, and educational and digital organisations. For example, a global software developer providing several public hospitals with integrated digital systems needs to comply with national regulations and specified budgets.

Individual healthcare organisations function as smaller systems, that are both shaped by and contribute to the broader system. Each hospital or health service is part of a regional health network within a national system. Also, a range of different nested systems exist within a hospital, such as an emergency department, operating theatres and rehabilitation team/s. Each small system creates its own workflows and practices, while people are the connecting networks.

Identify the local system

To plan implementation, it is important to identify the organisation and/or team in which the original challenge exists. This becomes the focus for understanding its organisational culture and assessing readiness for change. Geographically, it may be a hospital, primary care clinic, aged care facility, or community service. It will have a unique culture, leadership structure, staff dynamics, operational constraints, and improvement priorities.

Local healthcare organisations and their embedded systems interact with and are influenced by their broader healthcare ecosystems. Organisational actions are shaped by healthcare system pressures, like funding changes or regulatory requirements. Most healthcare organisations interpret and reframe the policies and budgets of the broad healthcare system. Systems Thinking helps to make sense of how these different systems interact and influence each other. For implementation to succeed, it is important to understand how parts of different systems function and how they influence each other.

Reflection Point

A big challenge for any implementation project is to work out which parts of different systems are relevant to consider. It will depend on a ‘working’ understanding of the healthcare organisation, and this can best be generated by engaging with stakeholders. It also depends on the size of the underlying challenge and the potential for improvement.

Ultimately, you need to understand the organisation’s readiness before investing in change, and the people best placed to reveal that readiness are your stakeholders. A comprehensive and progressive detailed analysis is presented, but in practice, choices about which tools to use need to be made.

Map Organisational System

Implementation researchers have created many frameworks to understand and analyse change within an organisation. It can be challenging to select the best theory or framework because of variations in the purpose and interpretations of research. Certain frameworks have become more popular and are often used by researchers and those working in academic partnerships.

Alternatively, business analysts often utilise SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) and PEST (Political, Economic, Social, Technological) analyses to understand how internal and external factors affect their healthcare organisation.

A generic and practical approach is proposed in this book, using systems thinking and behavioural theories. The sequence and activities can be used independently or in conjunction with academic theories and frameworks.

What is Organisational context?

Organisational context refers to the constellation of factors within and surrounding an organisation that shape how change is experienced, supported and sustained. It represents the intersection of the broader healthcare ecosystem, with the internal systems of a specific healthcare organisation. It includes the structures, cultures, policies, leadership styles, resources, relationships, and routines that influence day-to-day work. Consequently, it is often experienced as a layered set of systems that include internal dynamics, cross-departmental relationships and external influences.

Scan the external health ecosystem

To start the mapping process, zoom out to consider how your organisation fits in with the larger healthcare ecosystem. Recognise how national policies, regulatory frameworks, funding mechanisms, and professional organisations are likely to impact the proposed improvement. Often, these broad systems are not easily influenced by actions within smaller healthcare organisations.

Sketch out key elements that you will need to be aware of as you plan to implement a specific improvement.

Explore the internal organisational systems

Next, visualise how things work in your target organisation. There are many ways to do this. Ask key stakeholders to identify organisational charts and discuss hierarchical patterns of power. Look closely into specific departments or divisions, and their spheres of influence. Look for annual reports, strategic plans and regular performance reports where appropriate.

Locate the original challenge within the organisational chart and revisit earlier descriptions of current practice. The following tools are described to help identify key elements of the organisational system that can be influenced to support change.

Map care pathways

Look for a process map or flowchart of the way clinical services are usually delivered. Key stakeholders will be familiar with clinical or practice guidelines that describe the way care is delivered. For some services, there are clear stages in the delivery of care that patients must progress through. For example, on entry to the emergency department, there is a triage process, then an assessment process (including blood tests, imaging and other diagnostic assessments) followed by treatments and referral to an inpatient or external setting.

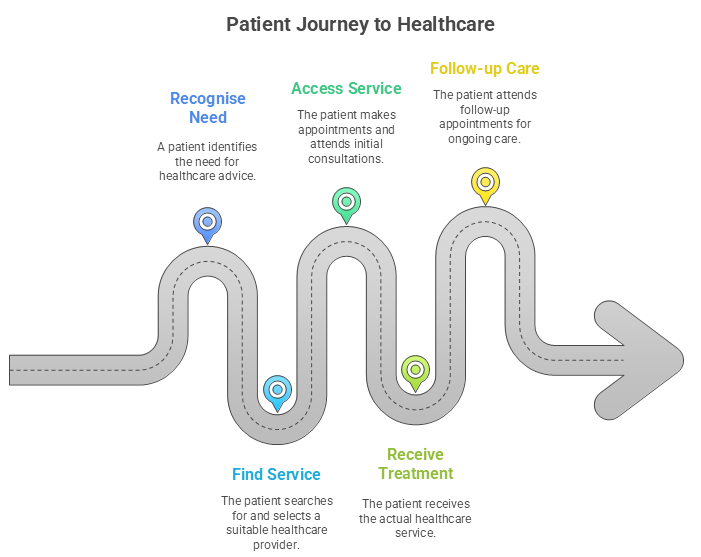

Map the patient journey

Create a patient journey map as a visual step-by-step representation of a patient’s experiences and interactions, from their initial recognition of a health need, through accessing services, receiving treatment, and ongoing or follow-up care. Through discussion with patients and their families, aim to describe and visualise their perspective of their journey through the organisation.

Use the guide below to get started and focus your discussion.

Communicate with Patients |

Make Sense of Patterns |

|

Consider carefully how you will ask patients to describe and/or draw every interaction they have with a specific health service. Choose from the following prompts as a basis for your interactions. |

Look for underlying patterns and relationships in each patient’s journey, compare across multiple patient journey maps, and with clinical care pathways. |

|

1. Look for common patterns and themes.

2. Identify variations, bottlenecks, and gaps in services.

3. Summarise key issues.

4. Highlight differences between patient journeys and clinical care pathways.

5. Investigate perspectives of health staff, especially around key differences. |

Map the connections

Compare the patient journey map and the clinical care pathway to identify where there is alignment between the proposed change and the organisational context. Look for variations in care, service bottlenecks and specific gaps in services and communication. These variations are rarely intentional and often reflect the complexity of the surrounding systems.

Consider what impacts the way in which the care pathway is reflected in patient journeys. Look for underlying patterns and relationships. Draw arrows to indicate who relies on whom or what, for each part of the process. Look for feedback loops that reinforce certain patterns and identify trends over time. Ask about what happens when things are delayed or missed.

By understanding how different parts of the system interact from multiple viewpoints, it is possible to anticipate unintended consequences and identify leverage points to drive change. The time taken to engage all stakeholders in these mapping processes can generate a shared understanding and build real engagement in change.

Measure current practice

Across every mapping process outlined, look for data that is routinely collected that measures or monitors aspects of performance. Data collection and analysis may not always be visible to clinical staff, but as digital systems are integrated, data is increasingly available.

Aim to summarise and measure the aspects of current practice that are not consistent with the evidence you have collated. There will likely be a Performance Gap between what is best practice and what is actually happening. Current performance is different from what would be required if the innovation or research evidence was actually being integrated into everyday practice.

There is also likely to be an Outcome Gap, which is the difference between the expected improvements described in the evidence or the pilot studies of innovation and the current clinical outcomes. Future chapters will highlight ways to monitor and measure changes in outcomes.

Frame a practical aim for improvement

These various forms of mapping help make an “invisible” process visible within a complex and dynamic system. Using the performance and outcome gaps, frame an improvement aim around WHAT will improve, and WHO will enable this, for WHAT benefit. For example, “If someone does something specific, we will be able to achieve something great that addresses our big problem”.

Evaluate Organisational Readiness

Mapping the organisational context sets the scene for evaluating organisational readiness. Change is most likely to succeed if key leaders are engaged, resources are available, and staff are confident and know what to do. Understanding readiness helps to identify the support that is needed to move forward.

Identify individual readiness for change

Sometimes, it is helpful to understand organisational readiness for change by conceptualising individual readiness. Individual readiness for change refers to an individual’s willingness and ability to do something differently. It usually incorporates a personal belief in the value and importance of a change, confidence in their ability to make the change, support from others and/or the environment and clarity about what the change involves. Work through the following personal challenge.

A personal challenge

- Create a personal intention to exercise.

- Then consider whether you know and believe the evidence that exercise is beneficial. Ask yourself if you have sufficient time, equipment and space to exercise. Who will help or support you to exercise?

A key factor will be how important this change is for you, and why you believe that it matters. Can you recognise the subtle difference between readiness and capacity for change?

Examine organisational readiness for change

Organisational readiness for change refers to how prepared an organisation is, psychologically and practically, to adopt and sustain change. While it can be measured at individual, team and organisational levels, it is commonly evaluated at the organisational level, in relation to a specific improvement.

Readiness refers to the capability and willingness of staff within an organisation to enact a reasonable change. It reflects a combination of:

- Motivation to change: Do people see the need and believe it matters?

- Capability to change: Do they have the skills, resources, and infrastructure to act?

- Contextual alignment: Is the change compatible with existing systems, priorities, and workflows?

When organisations are not ready, even well-designed changes fail to gain traction. People may nod in agreement but resist in practice. Assessing readiness before implementation allows you to adapt your approach to the local environment, prioritise which elements to tackle first, build momentum gradually and strategically and avoid wasting time, resources, or goodwill.

Assessing organisational readiness

Readiness assessment is rarely formal or rigid. It usually represents a summary of thoughtful conversations with stakeholders. Four key themes are proposed to synthesise this content.

Clarify the desired improvement

Use the practical aim for improvement to summarise what will improve, who will enable this, and for what benefit.

Highlight which of the following benefits of implementation are likely to be achieved:

- Improved patient outcomes

- Enhanced quality of care

- More efficient practices

- Better use of resources?

Evaluate proposed changes in context

Consider whether the proposed benefits are easily observable and recognised as important. Have results from pilot activities and research studies been shared to illustrate that these benefits are possible in other settings?

As you frame the details of the change, make comparisons with current care pathways and patient journey maps to highlight the advantages and ease of change. Demonstrate how well the improvement aligns with existing needs and workflows. Use the table below to inform these discussions with stakeholders.

|

|

Evaluation questions |

|

Relative Advantage How is it better than current practice? |

How will this change save time, improve outcomes, reduce costs, or add value? |

|

Compatibility Does it align with values, needs, workflows? |

How will it fit with organisational priorities, and limit disruption to routines? |

|

Simplicity Is it easy to understand and implement? |

What are the actual steps that need to change? |

|

Ability to Pilot Can it be tested before full implementation? |

Which small, interested group is ready to try it out, to understand what works? |

|

Observability Can the benefits be seen and measured? |

What data and success stories are available? |

|

Priority Are the proposed benefits important? |

Why is it important now to make this change? |

Anticipate challenges

When engaging with stakeholders, explore how the system is likely to respond to the proposed changes, recognising that any change can disrupt stability. Work together to identify potential risks, such as which groups, processes, or priorities might be affected. Consider the forms of resistance that may arise, whether emotional, political, or operational. By anticipating these risks, you can plan strategies to manage them proactively.

Remind yourself that problems rarely have a single cause in complex organisations. Inefficient or frustrating processes often persist because they support cultural norms and relationship needs for convenience, control, or predictability.

Be aware of competing priorities or change fatigue. In busy clinical environments, even well-supported projects can flounder if people feel overwhelmed or confused by too many initiatives. Also, consider the feedback loops at play. For example, if frontline staff don’t see leaders modelling the change, or if short-term results aren’t recognised, the system may revert to the status quo.

Leverage strengths and opportunities

Identify what is already working well. Look for existing relationships and routines that can be aligned with the improvement aim. Consider key touchpoints in the patients’ journey maps where staff interactions can make a positive difference.

Consider organisational assets such as connected teams, respected leaders, or a history of adapting to change. Look for teams or individuals who are already doing things differently and achieving better results. Identify early adopters and peer champions and involve them in the implementation process to create lived examples of success. Empower these relationships and informal networks to spread change through trusted pathways.

Interpreting readiness

Readiness is dynamic and can be influenced, potentially, as an implementation strategy. This will be discussed in more detail in the following chapters.

Ultimately, the organisation where implementation is being planned plays an important role in its success or failure. By engaging stakeholders, mapping the organisational environment, and recognising patterns and interrelationships in the surrounding systems, there are clues to understand the pressures and possibilities that shape how change is likely to unfold. These insights provide the foundation for planning how to support change. In the next chapter, the focus will be on identifying and supporting behaviour change.

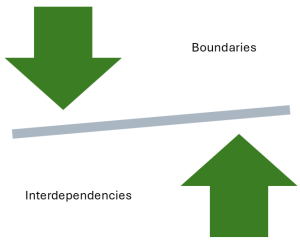

Navigate the Paradox Between Boundaries and Interdependencies

To understand a system, we must represent boundaries in mapping and analysis tasks. Yet systems are open, and behaviour is shaped by connections and interdependencies. In assessing readiness, we have clarified the boundaries of the desired improvement, to help make planning manageable. But in reality, these boundaries are rarely truly fixed. Change in one area inevitably creates ripples in others. Efforts to build readiness in one part of the organisation may uncover constraints, and unexpected enablers elsewhere.

This implementation paradox invites you to work within defined boundaries, while remaining alert to the interdependencies that shape the system’s response to change.

By engaging stakeholders and mapping organisational structures and processes, you can visualise how actions are connected, how behaviours are reinforced, and where influence travels.

At the core of this paradox is tension between managing scope without ignoring influence. Skilled leaders use system maps to illuminate how relationships and structures enable or hinder change, not to judge or isolate individuals.

Case Scenario – “Who else needed to be involved?”

Setting:

A community health service in rural Africa set a goal to reduce malnutrition among children under five, after repeated health surveys showed high levels of stunting and underweight growth.

Challenge:

Malnutrition is a leading cause of childhood illness and vulnerability in the district. It is a complex and challenging problem resulting from many factors including limited access to nutritious food, poor sanitation and hygiene, and low rates of exclusive breastfeeding.

Initial Action:

The community health service focused on what it could directly influence. Community health workers were trained to screen children during home visits, refer high-risk cases to the nearest clinic, and distribute educational leaflets on breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices. Donors and Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) also funded small-scale nutrition projects for families most at risk.

Despite these efforts, child malnutrition rates remained high. Nutrition programs reached only a fraction of the population, and children frequently relapsed after initial treatment.

Emerging Tension:

This initiative encountered the Boundaries vs. Interdependencies paradox.

The community health service had strengthened its activities within its own boundaries, and NGOs provided important support, but broader interdependencies were not addressed. Families lacked reliable access to diverse foods, seasonal shortages created long periods of scarcity, and women’s capacity to implement feeding advice was constrained by farming and household duties. Agricultural cooperatives, village leaders, and local schools were not fully engaged in the effort.

Turning Point:

The community health service worked with local government to map the wider system influencing child nutrition. They invited a broad group of stakeholders to a series of co-design workshops to better understand and address the problem of malnutrition.

Reflection Questions

- How well do you understand the boundaries of your team and the interdependencies that lie just beyond them?

- What elements of your organisational context support or constrain the change you’re trying to make?

Key Takeaways

1. National healthcare systems resemble ecosystems.

Healthcare organisations represent systems interacting within larger national ecosystems, where their actions are shaped by internal factors and external influences.

2. Organisational context shapes implementation success.

Organisational context refers to the internal structures, cultures, routines, leadership, and relationships that influence how change is perceived and adopted.

3. Mapping the organisational system reveals readiness for change.

Mapping helps visualise the organisation’s structure, roles, and interconnections, and can identify points of alignment, leverage, or resistance.

Additional Resources & Templates

Understanding Implementation Science Theories and Frameworks

- Wilson P, Kislov R. Implementation Science. Cambridge University Press; 2022.

Section 4 provides an overview of implementation theories and frameworks.

- If you want to read a comprehensive review of how researchers describe organisational context, I recommend this comprehensive article. Organisational contextual features that influence the implementation of evidence-based practices across healthcare settings: a systematic integrative review

- If you are working with researchers, you may need to access implementation theories, frameworks and models to guide you in this step. The following scoping review highlights the range of different frameworks and explains how each framework describes organisational context. Context matters in implementation science: a scoping review of determinant frameworks that describe contextual determinants for implementation outcomes

- One of the most common implementation theories is the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). You can access theoretical and practical information about using this framework at this website: https://cfirguide.org/.

Understanding Patient Journey Mapping

- A useful and practical blog to get started with developing a patient journey map is The Fundamentals of Patient Journey Mapping

- Another useful blog that discusses different types of patient journey maps is Patient Journey Mapping – How-To Guide for Healthcare

- An interesting academic article that describes developing patient journey maps in cardiology is here Patient journey mapping: emerging methods for understanding and improving patient experiences of health systems and services | European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing | Oxford Academic

Formal Organisational Readiness Evaluation Tools

If you are working with researchers or want to use an externally validated tool, here are 2 recommendations.

- American researchers have developed the Readiness Thinking Tool and it is well described in the post by Canadian researchers. Readiness Thinking Tool: Why Organizational Readiness for Change Matters

- An Australian dietitian has developed an Implementation Readiness Assessment Tool, as part of her PhD studies.

Available Templates

Access the templates on the author’s From Research to Reality webpage on the Mosaic website:

- Map a Specific Organisational System

- Patient Journey Mapping

- Organisational Readiness to Change Evaluation

A way of understanding how elements within a system interact, influence each other, and produce patterns of behaviour through dynamic interactions.

A visual diagram that outlines the sequence of steps or activities in a particular process from start to finish.

A visual representation of the patient’s experience across different stages of care, including emotional, informational, and clinical touchpoints.

A standardised, evidence-informed plan that outlines the optimal sequence and timing of care for a specific patient group or condition. Also known as Care Guidelines.

A theory-based method and intervention designed to address barriers and facilitate the adoption and integration of clinical innovations into healthcare settings.