Chapter 4 – Identify and Engage Stakeholders

Learning Goals

Use these learning goals to focus your attention, connect new ideas to your own context, and identify practical ways to apply what you learn. In this chapter you can:

- Identify individuals likely to be impacted by change

- Compare stakeholders’ power and interest in change

- Engage purposefully with stakeholders

Assess the Situation

Welcome to the first of two chapters designed to help you assess the situation at the core of your implementation plan. The focus of this chapter is to understand the system and the people within it, because implementation doesn’t happen in isolation.

Welcome to the first of two chapters designed to help you assess the situation at the core of your implementation plan. The focus of this chapter is to understand the system and the people within it, because implementation doesn’t happen in isolation.

In this stage, both chapters work closely together as overlapping and interdependent sets of actions. In reality, they often evolve together. Stakeholders are your most valuable source of insight into how an organisation works, and whether it’s ready for change. Engaging them early helps surface hidden dynamics, clarify priorities, and build trust. At the same time, mapping the system helps you see which stakeholders matter most, how they relate, and where resistance and support might arise.

Identify Individuals Impacted by Change

Ideally, implementation would be simple if the people who developed the innovation or conducted the research could just introduce change directly into their own routines. However, that is rarely ever possible. Most commonly, people do the research and develop innovations outside of the system in which they want to implement change.

Therefore, to plan implementation, it is important to identify people who influence and are influenced by the proposed change. They can include clinicians, managers, executives, patients, families, administrative staff, and external partners. Some people will be allies and others may be sceptical. However, they all hold important insights into how change works (or doesn’t) in an organisation. Their perceptions of the problem, the urgency for change, and the likely consequences may differ from yours, and from each other. This diversity is sometimes challenging, but valuable.

Collectively, the business literature describes these individuals as stakeholders. Identifying and engaging with them early will help uncover blind spots, anticipate barriers, and identify opportunities for alignment.

Recognise key stakeholders

The first step is to identify stakeholders across three interdependent functions:

- people needing to change their behaviour,

- people who make and influence key decisions to adopt change (or not), and

- people who will be affected by the change.

Comprehensively brainstorm all people who are likely to be impacted by the proposed change. Be sure to consider patients, consumers, their carers, family and community advocates.

Then, progressively start informal conversations to understand their perspectives. Explore their perspectives of the problem and whether change is required. These early conversations will likely focus on WHY the problem is important and WHY the change is needed. People also like to discuss the anticipated benefits. Many will have an opinion about the issue, the change, and the outcomes they want to see. Some will be aware of the evidence, and others will not.

Compare Stakeholders’ Power and Interest in Change

There are many tools to gain a deeper understanding of the different perspectives held by stakeholders. These tools are useful to help you prioritise who to engage with. They are built on information collected from conversations and a working knowledge of the organisation. Systems thinking skills are useful to look for patterns in relationships and networks, as people work and communicate together.

Comparing power and interest is fundamental in complex systems, where informal influence often matters just as much as formal authority. People with high power and low interest can limit progress when they feel excluded. Conversely, highly interested people with limited formal power can become strong advocates when they are empowered to act. Mapping these dynamics helps to anticipate where support might grow, and where friction may arise.

This work is sensitive. Power is often unspoken, and influence is shaped by history, personality, and politics. Therefore, it is often easier to create informal discussions about individuals’ interest in the challenging problem, and their awareness of, and agreement with, the evidence. Start with asking some general questions:

- Who is already talking about this issue—and how?

- Who makes decisions that affect this area?

- Who do others listen to or follow?

- Who might resist or feel threatened by the proposed change?

- Who has tried to make similar changes before?

- Who do I need to learn more from before moving forward?

It is not as straightforward to discuss individuals’ power in their organisation. Consider observing and asking about how decisions are made, who is commonly involved, and how change has happened in the past. Be aware that formal titles don’t always equate to decision-making power. Sometimes, people are influential because they hold institutional memories and have strong informal networks that shape what others believe is possible. Look for patterns in how formal and informal power are conveyed. Observe who gets asked to contribute, and who speaks up in meetings. Listen to the opinions that others defer to and note who people turn to when problems arise. These observations offer valuable clues.

Construct a matrix of stakeholders’ power and interest

Use a common project management tool, a Power-Interest matrix, to start to organise the patterns and perspectives emerging from informal discussions. Think strategically and systematically about the people involved and position them according to their relative power and interest in the proposed change. Estimate and make comparisons, rather than label people. This process helps to anticipate the different kinds of attention, communication, and involvement each group may need.

Construct a simple table and list local stakeholders in their relevant quadrant.

|

High Power, Low Interest |

High Power, High Interest |

|

|

|

| Low Power, Low Interest | Low Power, High Interest |

|

|

Often, it is easiest to identify people in the high power/high interest quadrant. They typically have the operational power to make decisions around the proposed change. Then look for all people who are interested in what is happening. Continue to allocate people across all quadrants.

Case Scenario – Stage 1 – Using the Power-Interest Matrix

A health service decides to implement a new medication safety protocol aimed at reducing prescribing and administration errors. The protocol introduces barcode scanning for medications and updated double-checking procedures. The new implementation team is aware that different stakeholders hold varying degrees of power and interest in the project. They use a Power–Interest Matrix to identify key stakeholders.

Medical, nursing and pharmacy directors have high power to support this project and high interest in its successful implementation.

Finance and procurement managers have high power as they control budgets and supply chains. Their level of interest is low because they see medication safety as outside their core responsibilities.

Junior doctors and ward nurses have low power and high levels of interest in this protocol. Their prescribing practices will be directly affected but they may have little decision-making authority.

Patients have low power and low levels of interest in this protocol. While they may benefit from safer care, they won’t really notice any differences in their prescriptions.

Engage purposefully with stakeholders

The power-interest matrix provides a framework to inform patterns of communication. Not all stakeholders need the same level of attention. The matrix helps to prioritise time and communication based on each stakeholder’s influence (power) and level of interest in the proposed change. It supports intentional investment of time and energy, where it will make the most difference, and avoids overlooking key people.

Different stakeholders require different communication strategies. It helps to distinguish between people who need to be involved in decision-making from those who only need updates.

Adapt communication

Each quadrant in the power-interest matrix calls for a different communication approach. It is summarised in the table below.

High Power, Low Interest

|

High Power, High Interest

|

Keep satisfied and informedThese people can affect the relative importance and trajectory of change. Provide targeted, high-level updates that align with their strategic priorities. Respect their time but demonstrate how this change aligns with their interests. Consider short briefings or executive summaries. |

Actively Monitor and ConsultThese are key partners to keep closely involved through regular meetings, co-design, and shared decision-making processes. Invite their input early, share ownership and maintain open communication. Invite steering groups, advisory committees, and leadership teams. |

Low Power, Low Interest

|

Low Power, High Interest

|

Monitor with minimal effortThese individuals may move into other quadrants over time. Avoid over-investing time, but remain respectful and transparent. Keep them informed through general updates or summaries.

|

Empower, involve and updateLikely to be frontline staff, patients, and peers who care about the issue. Their insights can be invaluable, and their advocacy can build grassroots support. Empower them to provide feedback and create newsletters and social media. Involve them in brainstorming workshops and working groups. |

Case Scenario – Stage 2 – Using the Power-Interest Matrix

Following the identification of key stakeholders for the implementation of a new medication safety protocol, the implementation team design their communication strategies to reflect stakeholders’ varying degrees of power and interest in the project.

Keep medical, nursing and pharmacy directors closely engaged through regular planning meetings and share detailed progress updates. Their leadership will model buy-in for others.

Keep finance and procurement managers satisfied with concise updates that link the protocol to reduced risk, cost savings, and compliance. Avoid overwhelming them with operational details.

Keep junior doctors and ward nurses informed with clear training resources. Ensure they have opportunities to provide feedback and raise concerns.

Monitor Patients’ perspectives by providing accessible information about any changes that will impact them, to maintain trust and awareness.

Note that if patient behaviours need to change, consider them in a high interest quadrant.

Mobilise and engage stakeholders

Use this analysis to focus engagement and communication activities where it matters most. Engaging with stakeholders throughout the implementation process strengthens every stage of change. It helps you understand the diverse interests, expectations, and pressures shaping the system, so your improvement efforts are grounded in reality.

Beyond identification, the work of engagement is relational. Build early relationships with those who have influence, insight, or lived experience. By involving people early, you can ask for advice, seek practical support, and build advocacy among those who can influence success. Their input ensures that strategies and outcomes are feasible and relevant in the local context. Stakeholders can help to clarify what people will need to do differently and how they will be supported to do this. Over time, these conversations build shared commitment for change.

Purposeful engagement also helps you optimise the use of people’s time and resources by aligning effort and energies with what matters most. Just as importantly, it provides an early warning system to identify potential risks or conflicts before they escalate. Together, you can address concerns before they escalate and build alliances before you need them.

Practical Strategies

Check in regularly with stakeholders to ensure that the ‘right’ people are being listened to, and are taking part in shaping the improvement. Even small, regular updates, conversations and invitations to contribute can build trust and momentum.

Project management structures are useful to support stakeholder participation in steering and working groups. Consider utilising communication forums and newsletters to provide regular updates and feedback.

The practical application of systems thinking enables a deeper exploration of the way individuals interact within their daily routines. Use analysis tools, such as fishbone or causal loop diagrams, to explore all possible contributing factors. From these contributing factors, look for connections between key tasks and people. Look for multiple interacting factors that contribute to, rather than cause, the problem.

You will also hear people talking about barriers and enablers for the change. Keep track of these and, in the next stage, behavioural theory will be used to investigate individual determinants of change, in such a way as to match appropriate implementation strategies.

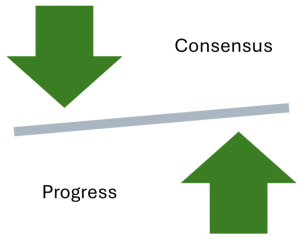

Navigate the Paradox Between Consensus and Progress

Engaging stakeholders builds ownership, insight, and legitimacy. Highlighting shared perspectives can shape forward progress. But involving everyone in every decision can slow momentum or dilute focus.

This implementation paradox represents the tension between creating broad engagement towards a shared purpose, while also knowing when and how to move forward.

We must build a broad consensus, while moving forward decisively. We need to create space for stakeholders’ input while holding focus.

Case Scenario – “Everyone Agreed, But Nothing Happened”

Setting:

A district health service planned to introduce an electronic referral system between hospital specialists and local primary care providers.

Challenge:

Referral processes were inconsistent, paper-based, and slow, leading to communication delays and poor visibility of clinical priorities.

Initial Action:

The project team invited a wide range of stakeholders to a series of design workshops, including GPs, hospital consultants, administrative officers, and IT staff. Participation was high for stakeholders who were interested in the new referral system. A prototype was selected, but progress soon stalled.

Emerging Tension:

The project represents an example of the Consensus vs. Progress paradox.

Despite strong initial interest, some people felt their priorities had not been fully addressed. Specialists wanted a range of structured templates to ensure referral quality. GPs pushed for an efficient and simple approach. Admin teams raised concerns about workflow duplication and software compatibility. The initial agreement was not sufficient for progress to occur.

The project team had not clearly identified which stakeholders had the power to decide, an interest to advocate, or concerns that could delay implementation. Without that clarity, they fell into a cycle of rework, trying to meet every request.

Turning Point:

A facilitative leader introduced a stakeholder mapping process. This clarified who to consult, who to involve in co-design, and who needed to approve each step. The revised engagement approach focused on purposeful communication, including frequent updates with high-influence managers, and focused discussions with high-interest users.

Reflection Questions

- How can you use early stakeholder mapping to identify who needs to be involved, and in what way?

- When there are different opinions and perspectives, how do you ensure everyone is heard and involved?

Key Takeaways

1. Identify and map all people likely to be affected by the proposed change.

Look to understand the full range of perspectives, needs, and potential influences within the system.

2. Compare stakeholders’ power and interest in the proposed change.

Construct a power–interest matrix to prioritise engagement efforts by identifying who can influence the change, who cares about it, and how their support (or resistance) might affect success.

3. Engage purposefully with stakeholders.

Involve and empower the right people in the right way at the right time, to build trust, address concerns, and create shared ownership of the improvement plan.

Additional Resources & Templates

Understanding Stakeholder Mapping

- A useful template and practical suggestions for using it are available at the Project Manager website.

This provides a useful guide for the processes of stakeholder identification and engagement. They use influence instead of power and importance instead of interest in their stakeholder matrix.

Understanding Stakeholder Engagement

This comparatively short and easy-to-read article describes how stakeholder engagement and process mapping techniques were used to implement a new home sleep apnoea testing program for patients in the Veterans Health Administration (VA) healthcare system in the USA. It includes some exemplar working documents. Table 1 highlights some key questions used to identify key stakeholders.

Interestingly, these researchers describe preparing initial process maps and then engaging in an iterative process with stakeholders to help refine and improve the workflow diagrams. They also highlighted the need to understand organisational structures and roles to effectively identify and engage stakeholders.

Available Templates

Access the templates on the author’s From Research to Reality webpage on the Mosaic website:

- Stakeholder Mapping Template

- Stakeholder Engagement Template

- Navigate People and Influence

Individuals or groups who are affected by, involved in, or can influence the implementation effort.

The application of knowledge, tools, and techniques to plan, execute, and complete a defined project within scope, time, and budget.