Chapter 3 – Position the Evidence

Learning Goals

Use these learning goals to focus your attention, connect new ideas to your own context, and identify practical ways to apply what you learn. In this chapter you can:

- Explore research, organisational and narrative evidence

- Collate the evidence for change

- Frame the case for improvement

Clarify the Challenge

The move from recognising a problem to building momentum for change requires a compelling, evidence-informed vision of what better could look like. A clear picture of current practice can focus the search for what’s possible around credible evidence. The aim of collating different types of evidence is to justify the change and reframe the problem in light of what the system could become. It can guide thinking from “what’s wrong” to “what’s possible.

Welcome to the second of two chapters designed to clarify the challenge at the core of your implementation plan. The focus of this chapter is to explore and collate the evidence around a future improvement that addresses the core problem and is relevant to current practice.

Welcome to the second of two chapters designed to clarify the challenge at the core of your implementation plan. The focus of this chapter is to explore and collate the evidence around a future improvement that addresses the core problem and is relevant to current practice.

Healthcare has a strong scientific background, where research and data are highly valued. There are exploding bodies of research evidence and increasing numbers of clinical guidelines. While these are necessary to guide change, they are not sufficient. Successful implementation requires comprehensive forms of evidence to be carefully positioned, to drive meaningful and credible improvement.

To create an aspirational future, evidence from several trusted sources builds the practical argument for change. This evidence comes in many forms, including research findings, local performance data, lived experience, and practical insights. Each form of evidence plays a role in clarifying the problem and building a case for change. This chapter will explore three different types of evidence and explain how they support implementation.

Explore Research Evidence

Research evidence is key for supporting the need for change. The traditional focus of implementation science has always been on translating research evidence into practice.

Research evidence that is useful helps clarify the problem in another setting and explains how specific interventions generate benefits, often in the form of clinical outcomes.

To get started, look for research around similar problems, change ideas, and patient populations. There are many ways to consider the quality of research papers. Conversations with research active colleagues and engaging with structured processes of critical appraisal can be helpful. In essence, ensure there are clear research aims, the methods are appropriate, and outcomes are clearly described in relation to the original question.

Ideally, look for research that summarises and synthesises other research, such as systematic and scoping reviews. These reviews summarise large volumes of research using consistent and rigorous methods. Systematic reviews typically assess the quality of included studies, allowing you to be more confident in their conclusions. Scoping reviews tend to map the breadth of evidence to confirm what is known and highlight gaps.

Read critically to understand the process and outcomes of change. As you read, consider how the benefits may be able to be realised locally. This research evidence is critical to strengthening the credibility of proposed changes.

Search for research studies

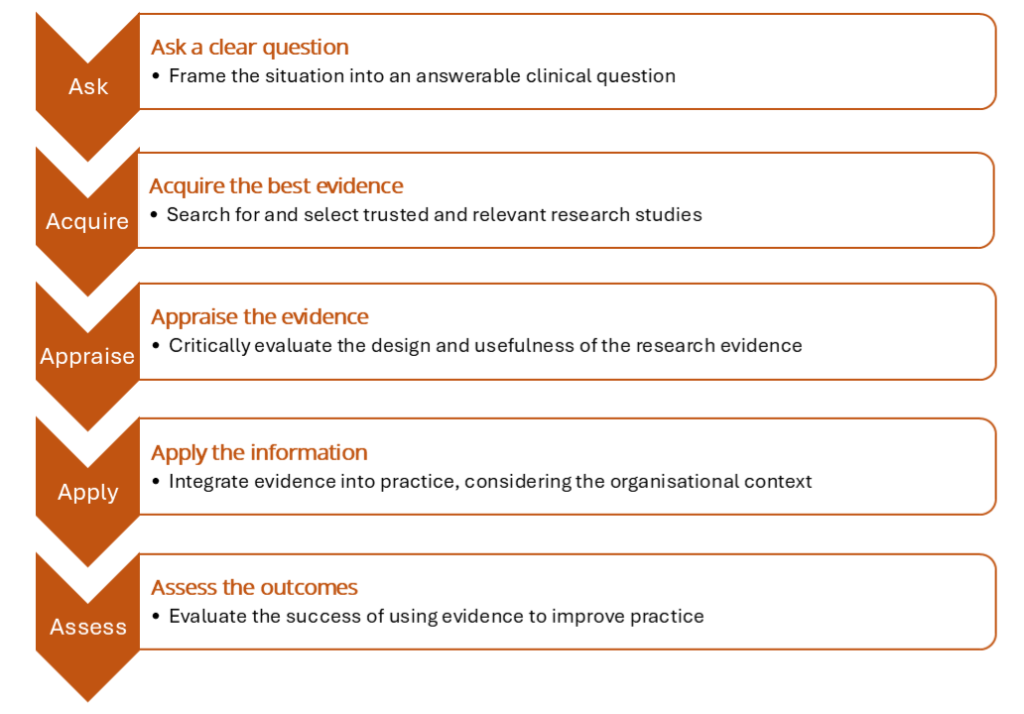

Over the last 20 years, a range of practical strategies have been designed to help clinicians utilise and understand the research evidence. A simple PICO framework can transform a broad or unclear problem into a focused, answerable question. This question then guides the literature search. It is explained, with examples in the PICO table below.

|

|

Description | Examples |

|

Patient Population Problem |

Describe the people, their health condition, or the processes within the problem |

For adults with knee osteoarthritis, For hospitalised adults ready for discharge, |

|

Intervention Exposure |

What clinical or process intervention is considered? |

…is supervised exercise better than …are digital discharge checklists better than |

|

Comparison Control |

What is currently being used, or are there other alternatives? |

… general exercise recommendations … unstructured practice guidelines |

|

Outcome |

What effects or improvements would you like to see? |

…for physical function & pain management? …for efficient hospital discharges? |

The two questions generated from this framework can be summarised as:

- In adults with knee osteoarthritis, do supervised exercise programs improve physical function and reduce pain compared to general exercise recommendations?

- In hospitalised adults ready for discharge, does using a structured digital discharge checklist reduce time to unstructured practice guidelines?

This PICO framework supports the first two steps of the common five-step approach to evidence-based practice, illustrated below. When relevant research articles have been identified, tools for critical appraisal help to separate high-quality evidence from poorly designed and misleading research. This guides the interpretation and application of research for practice. This process can be challenging to use, and where possible, seek assistance from research colleagues and/or librarians to help you do this.

Look for clinical guidelines

Clinical practice guidelines are practical summaries of research evidence. They are usually developed by expert panels and endorsed by professional bodies. They summarise the highest quality research evidence and provide practical processes and recommendations for practice, often presented in the form of a clinical pathway. However, they do take time to be developed and make their way into practice. There may be a time lag between when research is completed and when it is included in clinical practice guidelines.

Guidelines are also useful for identifying gaps and variations in the provision of healthcare and for benchmarking current performance. Look for unexplained variation in the application of guidelines within your own service and between different similar healthcare organisations, which might be contributing to the identified problem. Further, use benchmarks to make comparisons across other similar settings.

An awareness of background research and clinical practice guidelines is also important for introducing innovative products or practices. Often, the research evidence suggests reasons why the innovation is necessary. Small-scale tests of change and innovation provide real-world insight into what might work in a particular setting. Learning from pilot studies helps refine ideas before broader implementation and demonstrates feasibility. Utilise case studies and lessons learned from other innovation projects to support decisions about how to implement.

Explore Organisational Data

Every healthcare organisation has a unique way of operating, and this is often evident in internal routine documents and data management systems. This data about the organisation provides the context that connects an important problem to the wider priorities, pressures, and performance of the healthcare service. Useful sources include audits, incident reports, key performance indicators, and strategic or business plans. Look for routinely reported measures, such as wait times, workforce capacity, patient outcomes, and other quality metrics. These often provide a snapshot of how the system is currently functioning. Collecting this evidence not only illustrates current practice but also highlights performance gaps and creates a compelling case for why change is needed.

Policy and priorities

National policies, regulatory frameworks and funding mechanisms all guide the way healthcare is delivered. Many healthcare organisations reframe these requirements for local application. They also tend to highlight important aspects through local strategic plans and priorities. These provide direction and legitimacy for change.

Therefore, it is important to be aware of how you can position proposed improvements within policy and strategic priorities. This helps secure organisational support and alignment with broader goals.

Explore Narrative Evidence

Narrative evidence captures meaning, lived experience, aspirations and contextual insights. This includes consumer stories, staff experiences, and professional reflections, often collected through interviews, surveys, focus groups, or informal conversations. When searching the literature, use terms such as ‘lived experience’, perceptions, values and insights.

When talking to consumers and healthcare users, ask the following questions:

- How do people experience the system?

- What do they value or find frustrating?

- What feels possible from where they stand?

Professional expertise

Qualitative insights from staff help reveal why the problem persists and how it is experienced. Clinicians often hold deep knowledge based on experience. Many have already interpreted research evidence and made local adaptations. Healthcare staff have lived experiences of how practice is constrained and influenced by the surrounding organisational systems.

Consumer experience and feedback

Patients and families provide valuable perspectives on what matters most to them. Their input can highlight blind spots in clinical care and suggest ways to better reflect their needs. It is important to balance any formal surveys with informal conversations, to complete the full picture of lived experience.

Collate the evidence for change

Together, research, organisational, and narrative evidence each offer a vital perspective in shaping the case for improvement. These perspectives continue to clarify the problem and provide a rationale and direction for improvement. When evidence is positioned well, it acts as a lever for change. It identifies possible outcomes and clarifies how to get there.

Research evidence identifies practices that have worked in other settings, highlights important outcomes and identifies how they can be achieved.

Organisational data provides the practical framework for why change is crucial and emphasises the importance of addressing the original problem.

Narrative experience highlights relevant aspects of the research evidence and organisational practice that are comparatively significant. These lived experiences emphasise why change is necessary and what improvements might look like in practice.

By bringing this evidence together, you also highlight the distance between what is known and what is currently done.

Frame the Case for Improvement

Clarifying the challenge reflects a process of discovery. In the last two chapters, you’ve explored the value of stepping back to understand current practice and stepping forward to gather evidence about what’s possible. You have described where the system is now and started to imagine and discuss where it could go. Together, these perspectives help you frame a case for improvement that is supported by evidence, grounded in reality and shaped by multiple voices.

Together, these three types of evidence contribute to a grounded and persuasive case for why change is needed now. Use them to:

- Clarify a better future.

- Justify the urgency and relevance of change.

- Identify realistic benefits and anticipated outcomes.

You are now ready to plan the implementation into practice of a specific improvement that is informed by evidence and addresses an important local challenge. To do this, the next two chapters explore more deeply the people involved and the place where this change will occur.

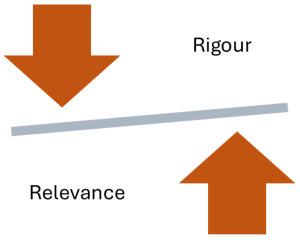

Navigate the Paradox Between Rigour and Relevance

In complex systems, this case for change is likely to shift through planning and implementation. New insights will emerge from any or all forms of evidence. We have emphasised that quality evidence from multiple sources provides credibility to change. This rigour is necessary, but not sufficient for change. To make a real impact, evidence must also be relevant, and it must describe the lived reality of staff and patients.

This implementation paradox represents the tension between valuing rigorous evidence while also ensuring it is relevant and meaningful in a specific context.

What is rigorous in research may not always resonate in practice. We must draw on both high-quality studies and local wisdom.

Case Scenario – “Is the Evidence Clear Enough to Act?”

Setting:

A rural family is raising a 15-year-old boy with type 1 diabetes. He manages insulin therapy with support from his parents and local health providers but feels socially isolated. Opportunities to attend camps or join sports teams are limited by both geography and his reluctance to be “different.”

Challenge:

The local Children’s Health Service is concerned about supporting teenagers with chronic illness, so they can self-manage their conditions as young adults. The team leader has read about the Chronic Illness Peer Support (ChIPS) program at The Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network. It is described as a structed peer support program that facilitates young people to learn about and manage their own health. Research shows that participation in the program builds peer networks and better individual management.

Initial Action:

As the team leader reviewed the key research papers, he read about professional insights, patient and family perspectives and clinical outcome data. This mix of evidence was very encouraging, and he discussed the idea of developing a similar program for local young people with the team.

Some team members were concerned that the research evidence only reports on ChIP programs in metropolitan settings. It is not clear whether it would work in a rural setting. However, they did agree that peer support is important for their teenagers as they move into adulthood and need to be able to manage their own medication and lifestyle choices

Emerging Tension:

They are experiencing the Rigour vs. Relevance paradox.

Team members collect evidence about their local context to clarify the need for a peer support program. They confirm the number of local teenagers and highlight the current gaps in their ability to support them. The challenge becomes clear. They need to balance the rigour of scientific evidence with the relevance of real-world experience and local priorities.

Turning Point:

The turning point comes when the local team identifies a gap between what the research evidence says is important and what they are doing. The team leader spoke to colleagues in Sydney to understand how the CHiP program has been delivered. They decide to take the time to build an implementation plan for introducing the CHiP program into their local health service.

Reflection Questions

- What challenges have you experienced in translating research evidence into your setting?

- How do you determine what is relevant and meaningful in your setting?

Key Takeaways

1. Research, organisational and narrative evidence offer complementary perspectives of the original challenge.

Together, they build a more complete, credible, and locally relevant understanding of the problem.

2. Collating evidence strengthens a case for change.

Collectively, evidence can align what’s known, what’s happening, and what matters most in a specific area of clinical practice.

3. Frame the case for improvement.

A well-framed case for improvement connects the evidence to a clear outcome and clarifies the opportunity for better care, often motivating people to act.

Additional Resources & Templates

Understanding Evidence Based Practice (EVP)

To familiarise yourself with Evidence-Based Practice methods for finding research evidence, here are links to 3 useful sets of resources.

- The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine at the University of Oxford maintains a list of tools and resources. EBM tools — Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM), University of Oxford

- The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme offers free downloadable checklists to guide the process of critical appraisal across many different study types, alongside guides to use these resources, to check clinical research for trustworthiness, results and relevance. CASP – Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

- Charles Sturt University Library provides a useful guide to understanding EBP, with links to many external resources. What is EBP? – Evidence-Based Practice – Library Guides at Charles Sturt University

Using Generative AI systems to search for research evidence

There is a range of Gen AI programs being designed to search for research evidence. They all have differences in what they offer in their free and subscription versions, as well as in their presentation of responses, citation practices, and accuracy. Be aware that not all research is included, and that AI tends to oversimplify evidence.

While these tools can be very efficient, ensure you check, cross-check and compare between systems and with trusted colleagues. Research active staff often have excellent time sensitive advice. Consider looking at the following tools:

- Consensus.app: Scans open access research papers and extracts conclusions from multiple studies, providing clear citations and quick summaries.

- SciSpace.com: Useful for broad searches and summaries across academic journals and grey literature.

- OpenEvidence.com: Useful for searching for and summarising clinical research, integrating articles from JAMA, Mayo Clinic Platform & New England Journal of Medicine.

- Perplexity.ai: Useful for general purpose searches in natural language, for research studies, general blogs and policy papers.

- Notebooklm.google: Provides summaries of research articles within a knowledge notebook format.

For an academic perspective, the following systematic review shows that while GenAI is not suitable for evidence synthesis without human involvement or oversight, it may be useful in assisting humans with evidence synthesis.

Understanding the evidence for the CHiP program

- Review the NSW government website that describes the program

- Read the news report about supporting young Western Australian children living with a chronic illness.

- Here is a key summary research paper

Available Templates

Access the templates on the author’s From Research to Reality webpage on the Mosaic website:

- Explore the Research Evidence.

- Collate the Evidence for Improvement.

Decision-making that integrates research evidence with clinical expertise and patient preferences.

The process of applying research findings and integrating beneficial evidence-based interventions into routine clinical practice.

The study of methods and strategies to promote the uptake of evidence-based practices and clinical innovations into routine care.