Chapter 1 – Explore the Implementation Landscape

Learning Goals

Use these learning goals to focus your attention, connect new ideas to your own context, and identify practical ways to apply what you learn. In this chapter you can:

- Explore core principles of change within healthcare systems

- Idenitify sequences of action towards improvement

- Navigate the paradox between complexity and simplicity

The Promise of Research and Innovation in Practice

When research and innovation are meaningfully integrated into regular healthcare practice, they hold the promise of delivering safer, more effective, and more efficient care. Evidence-based practices can reduce variation, improve outcomes, and support better use of limited resources. Innovations, whether technological, procedural, or relational, can address persistent challenges, modernise outdated processes, and meet the evolving needs of patients. For healthcare professionals, engaging with research and innovation can also reinvigorate practice, strengthen professional confidence, and contribute to a culture of learning and improvement.

Despite growing volumes of health research and emerging innovations, many proven practices are slow to reach the point of care. This disconnect means that patients may not benefit from the best available evidence, and clinicians may lack the tools or support to change how care is delivered. The challenge lies in using research and innovation in routine practice to reduce the distance between what we know works and what we actually do.

In contrast, the reality for many clinicians and health leaders is an environment of overwork and frustration. Promising ideas often stall, research evidence fails to become embedded, and efforts to introduce innovations lose momentum and are often delayed. Variations within and between health systems influence how patients can access new diagnostics and treatments. Health professionals experience frustration and burnout when they feel that they are not providing the best possible care. When resources are allocated to existing treatments that provide little benefit, healthcare systems may miss opportunities to improve patient outcomes and operational efficiencies.

The process of reducing the knowledge practice gap is more complex than many people recognise. It is not simply a logistical issue that can be better connected. A range of reasons for this gap exist and will be discussed in this book. Similarly, strategies that can address these challenges will be shared.

Core Principles of Change in Healthcare Systems

The ten core principles highlight why bridging this gap is so challenging. Implementing evidence into practice is not simply a matter of knowing what works. It requires people to do things differently.

Behaviour change is core

At the heart of any improvement effort lies behaviour change. If people continue doing what they’ve always done, nothing changes. That’s why organisational change requires behaviour change. For example, changing clinical routines involves more than gaining agreement; it requires individuals and teams to adopt new habits in the context of busy environments.

Too often, managers assume that providing the right information will naturally translate into new behaviours and improved systems. While individuals need to know what to do, information alone is not enough. Lasting improvement depends on enabling people and providing a range of practical supports and reminders to shift their daily behaviours.

Behaviours are shaped by a dynamic mix of individuals’ capabilities, opportunities, and motivations. They are also influenced by broader system conditions and previous experiences. Consequently, behaviour is driven by multiple factors. A clinician might be willing to try and introduce a new product, but if they lack protected time, access to tools, or confidence in the process, change often stalls.

Even motivation is complex and contextual. It’s not just about effort or attitude. Motivation represents both individual intentions and the routines, emotions and habits that propel most daily action. Uptake of a new practice may depend on whether it aligns with a clinician’s values, their trust in the source of the change, or their sense of professional autonomy.

For all behaviour change, individuals need time and space to learn about what is required. Even when individuals know what to do, a safe place to practice and hone the skills improves their confidence and self-belief in a new pattern of behaviour. Further, these learning and practice opportunities must be enabled amidst competing pressures and time constraints in busy work environments. Too often, it is assumed that health professionals know what to do and how to do it because they learned about it somewhere else!

Without attention to these multiple influences on individuals’ behaviour, implementation efforts risk being incomplete or unsustainable.

Organisational systems influence behaviour

To complement this focus on individual behaviour change, it is important to acknowledge that organisational structures shape individuals’ actions. People behave in ways that their healthcare systems support. At the same time, healthcare systems are structured in ways that often reinforce the status quo. Policies and regulations enforce adherence. Even when new practices are evidence-based and well-intended, they may struggle to gain traction if existing workflows, infrastructure, or reporting systems are not designed to support them. Clinicians might want to adopt a new documentation approach, but the electronic system they use makes it cumbersome or inefficient.

Healthcare systems are not faceless machines that can be repaired and tuned up. They represent a unique combination of structures, processes and services, between which there are interacting and interdependent relationships. Every healthcare system has a specific combination of health professionals who interact with administrators, patients and their families. Within these systems, people act within relationships. A strategy that is technically sound may still fail if it lacks support from respected peers or alignment with team values. When clinicians see their colleagues engaged in a new practice or are invited to shape the process themselves, they are more likely to take part.

Above all, change efforts need direction and alignment. That’s why a shared purpose is so important. As individuals work towards a shared purpose and make progress towards clear goals, they understand why change matters and how they can contribute. Over time, they are more likely to stay engaged, even when things get tough. When those involved in delivering a healthcare service help co-design their new pathway, they are more likely to commit and contribute.

The promise of implementation science

Over the last few decades of implementation science research, many practical implementation strategies have emerged to support behaviour changes in complex healthcare systems. The process of implementation is built through practical planning. Strategies need to be tested, adjusted, and adapted over time. Even with detailed description, analysis and planning, outcomes in complex systems will be both predictable and unpredictable. Therefore, ongoing monitoring and adjusting is required for sustained improvement. A phased rollout of a new clinical pathway, with feedback loops and opportunities to learn from what’s working, helps maintain momentum and build confidence.

Finally, just as no two people are the same, no two healthcare organisations are the same. An implementation strategy that works in one healthcare setting may fail in another. Successful implementation recognises that one size does not fit all. Effective change leaders adapt strategies to local needs, constraints, and relationships, ensuring that solutions are relevant, feasible, and embraced by the people they are meant to support.

Ultimately, successful implementation depends on enabling both individual action and collective alignment within each health system. The Ten Core Principles are summarised in the following table.

|

|

The Ten Core Principles |

|

1. Organisational change requires behaviour change |

Lasting improvement depends on people doing things differently. Often, more than one person must change their behaviour. |

|

2. Information alone is not enough |

Evidence must be supported by reasons and strategies for behaviour change. |

|

3. Behaviour is shaped by multiple factors |

Change requires consideration of individuals’ capabilities, opportunities and motivations to act. |

|

4. Motivation is complex and contextual |

Motivation is more than willpower, and is shaped by habits and emotions, which vary across people, settings, and time. |

|

5. Capability must be enabled |

Every person needs the right support, tools, time, and permission to enact change. |

|

6. Systems shape behaviour |

Clinical and organisational systems maintain the status quo. |

|

7. People act within relationships |

Social dynamics and trust influence how change is perceived. |

|

8. A shared purpose enables change |

Clarity of purpose and shared ownership help people stay committed, especially when challenges arise. |

|

9. Implementation requires practical planning |

While research evidence and behavioural analysis offer valuable insights, success depends on flexibility, iteration, and the ability to adapt within complex systems. |

|

10. One size does not fit all

|

Implementation strategies must be adapted to the specific context in which change is occurring, the people, pressures, patterns, and possibilities. |

Example scenario incorporating the Ten Core Principles

A large health service decided to strengthen its culture of research by creating an Allied Health Research Fellowship Program, following an internal audit of research activities. Leaders were keen to introduce research-informed strategies, including allocating protected time to selected clinicians, providing mentoring, and offering structured opportunities for developing local research projects.

To implement this program, some clinicians changed how they worked, and managers adjusted staffing schedules. When leaders valued research outputs as part of their performance expectations, they created space for research alongside clinical duties. This organisational change required behaviour change across multiple levels.

Early on, the team realised that information alone was not enough. Access to online training materials and practical resources didn’t automatically lead to quality research projects. What made a difference was active mentoring, peer discussion, and supportive feedback. These practical enablers actually built genuine capability.

Progress varied as clinicians’ behaviour was shaped by multiple factors. Some had strong mentors and departmental support, while others struggled with heavy caseloads. Their motivations were complex and diverse. Some sought career advancement, others wanted to improve patient care, and a few were driven by personal curiosity. The program team adapted its support to individual circumstances.

It was also evident that the broader healthcare systems shaped some behaviours. Progress was slowed by approval processes for ethical review and backfill arrangements. In contrast, clear selection criteria and mentoring guidelines enabled progress. Careful program planning was required to keep clinicians aligned and motivated. Yet, flexibility was key. One size did not fit all. Different disciplines and departments required different types of support.

Relationships proved to be just as important. Clinicians who connected with supportive mentors, engaged their managers, and built networks with like-minded peers were able to move forward more confidently. What united the program was a shared purpose to engage more allied health clinicians in research. By aligning fellows’ research projects with organisational priorities, the program demonstrated tangible value to clinicians, executives and patients.

By weaving these core principles together, the fellowship program demonstrated that engaging clinicians in research requires an understanding of the interplay between individuals’ behaviour, the organisational context, and personal relationships. These principles provided a practical way to guide and make sense of the implementation process.

Reflection Questions

As you reflect on these ten principles, ask yourself:

- Which principles align with how I work?

- Which principles might I need to consider more deeply as I plan for and lead change?

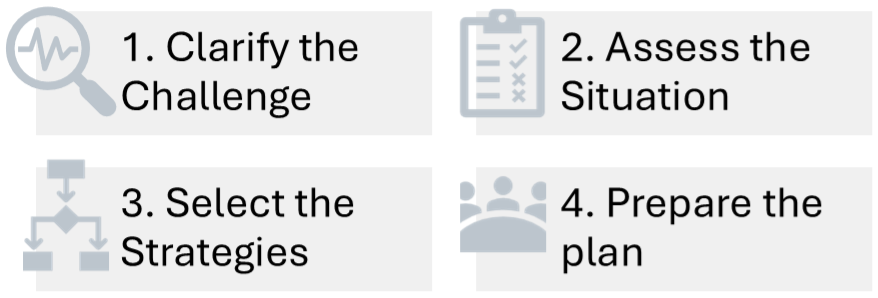

A Sequence for Action

Every improvement begins with an idea. This book is built around a practical guiding framework, representing a sequence of four broad actions. Each action encompasses a range of relevant strategies and practical tools, which, together, form a coherent pathway to meaningful, lasting change.

1. Clarify the challenge

Before designing any change effort, it is essential to define the real problem and understand why it matters. The challenge may arise from a persistent problem in practice, recognition that research guidelines are being inconsistently used, or a desire to introduce an innovative process or product that offers promise for a specific group of patients. In complex systems, what first appears to be an issue or an opportunity is often underpinned by deeper patterns and relationships around providing care.

Clarifying the challenge means digging below the surface to examine where care is falling short, who is affected, and what the consequences are. It is important to identify a gap in practice and to understand the human and systemic behaviours that sustain it.

2. Assess the situation

Once the challenge is clear, several paths to improvement may emerge. Therefore, it is important to assess the organisational context and identify who is likely to influence and be impacted by the proposed change. Local stakeholders are key to exploring and understanding the organisational context and its readiness for change. Discussions around what people know and believe can be complemented by observations of habits and structures that influence how things are currently done.

Ideally, knowing how the system functions helps to frame what you’re working with and where the leverage points lie. Current workflows and routines are reinforcing, and people act within existing relationships of authority and influence. Mapping the organisational culture, stakeholder interests, and environmental pressures provides a more accurate picture of what must shift and where to start.

3. Select the strategies

With clarity of the challenge and the context, the focus turns to selecting appropriate implementation strategies. Through engaging with key stakeholders, key barriers and enablers for change become clear. A simple model of behaviour change guides a practical analysis of these determinants and a process of matching appropriate implementation strategies.

While it can be useful to know what works elsewhere, effective implementation requires aligning strategies with local behavioural and contextual factors. Stakeholders are crucial for practical planning and co-designing bundles of feasible strategies to guide the proposed change.

4. Prepare the plan

The final step in the sequence brings everything together into a feasible and adaptive implementation plan. It involves co-designing a practical roadmap to guide action, support learning, and adapt to changing conditions. In addition, a carefully constituted logic model can include measures of success, roles and responsibilities, timelines and space for iteration. These tools are useful for navigating complexity and anticipating both expected and unexpected consequences.

Crucially, the plan also builds shared ownership. When developed with the people who will carry it forward, it strengthens alignment, reinforces purpose, and increases the likelihood of sustained engagement. It brings the full sequence to life by connecting context, strategy, and structure into a cohesive, locally relevant approach to meaningful improvement.

Examples of A Sequence for Action

Clarify the Challenge

Every improvement begins with defining the real problem and understanding why it matters.

In one hospital, benchmarking data revealed that patient falls on medical wards were higher than national averages, raising safety concerns.

In a rehabilitation unit, a junior occupational therapist noticed that stroke patients were being discharged without personalised guidance for their daily activities, leading to poor clinical outcomes.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, clinicians recognised the important challenge of monitoring patients with chronic diseases who did not want to attend healthcare clinics.

Assess the Situation

Before jumping to solutions, it is important to understand the local context.

On the wards, staff and data confirmed that most falls occurred at night and that fall-risk screening was inconsistent.

In the rehabilitation unit, the new graduate spoke with patients and colleagues to discover that generic recommendation handouts were rarely useful and often lost.

During the pandemic, there was significant variation in digital infrastructure, remote monitoring devices, and levels of readiness for change among patients and clinicians.

By carefully assessing each situation, practical barriers and enablers that shaped each challenge were identified.

Select the Strategies

It is crucial to match implementation strategies to local needs, barriers and enablers.

The falls project introduced standardised risk assessments, appointed ward champions and improved evening care routines.

The junior therapist created simple, pictorial handouts personalised to each patient’s priorities, and trialled follow-up phone calls.

Health leaders prioritised wearable devices and apps that allowed real-time monitoring and introduced training for both clinicians and patients.

Each initiative selected strategies that were feasible, evidence-informed, and responsive to local needs.

Prepare the Plan

Finally, integrate insights into a feasible implementation plan.

The new falls program was piloted on selected wards, with weekly data monitoring, so that it could be spread across other wards when successful.

In stroke rehabilitation, the discharge process was redesigned so that therapists used a digital program to prepare personalised pictorial handouts, while junior staff rotated responsibility for follow-up phone calls.

For digital monitoring, phased rollouts of specific apps were developed with clear governance, evaluation of patient outcomes, and adaptation as technology matured.

In every situation, the plan incorporated relevant strategies and measures that could document real improvements.

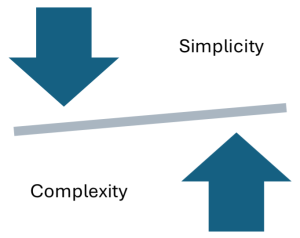

Navigate the Paradox Between Simplicity and Complexity

One of the central tensions in implementation is the need to plan clearly without oversimplifying the reality of complex systems.

This first paradox represents the tension between a desire for simple, actionable frameworks to make change manageable and the ability to understand the complexity of behaviours and relationships in complex healthcare systems.

This first paradox represents the tension between a desire for simple, actionable frameworks to make change manageable and the ability to understand the complexity of behaviours and relationships in complex healthcare systems.

At the core of this paradox is tension. To make progress, we must simplify, without oversimplifying. A good implementation plan is a flexible roadmap, grounded in evidence but open to adaptation. It reflects both the need for coordination and the unpredictability of context.

Recognising this paradox helps avoid too much or too little control. We need to act with structure but think in systems. Look for clarity without oversimplifying the unpredictable nature of human behaviour and organisational life.

Case Scenario – “Let’s Just Get It Done”

Setting:

A busy metropolitan hospital’s emergency department (ED), is facing increasing demand and long patient wait times.

Challenge:

A project team was established to implement a new triage protocol designed to fast-track low-acuity patients. It was successful in a similar hospital and came with a clear set of instructions.

Initial Action:

The protocol was introduced through a one-hour training session, available in person and online, and posters were placed in triage areas. The implementation plan focused on a quick roll-out of a clear and logical protocol, and regular reporting of wait time data.

Emerging Tension:

The team quickly ran into the paradox of simplicity versus complexity.

Although the protocol was clearly defined, uptake was patchy. Some staff adapted it informally; others resisted entirely. Senior nurses flagged that there was a conflict with the current practice of managing patients with mental health presentations. Meanwhile, data showed no sustained improvement in wait times.

Project leaders realised they had oversimplified the problem. What appeared to be a straightforward and logical improvement was, in fact, embedded in a complex web of patient needs, staff routines, team dynamics, and unspoken workarounds.

Turning Point:

Instead of pushing for stricter compliance, the project leads paused to consult frontline staff. They mapped the broader system of triage decision-making and invited feedback from different teams.

Relection Questions

- Where in your own setting have simple solutions failed to account for complex realities?

- What might you need to pause or revisit to better understand the system you’re trying to change?

Key Takeaways

1. Effective implementation begins with a clear challenge.

Understanding the real challenge and why it matters creates a strong and shared purpose for change.

2. Planning implementation involves understanding people, patterns, and possibilities.

Sustainable change depends on more than evidence. Understanding behavioural, organisational, and system factors enables capability, shapes motivation, and adapts implementation strategies to address local needs.

3. A well-prepared plan connects structure with flexibility.

Practical planning provides a roadmap for coordinated action, and success lies in balancing simplicity with complexity.

Additional Resources & Templates

Resource:

- The Complexity Lens is a LinkedIn Newsletter that helps health leaders make senser of complex systems and lead change with clarity and confidence. Available at https://www.linkedin.com/newsletters/the-complexity-lens-7315695476425560064

- The following articles summarise a significant pipeline of research.

Available Templates:

Access the templates on the author’s From Research to Reality webpage on the Mosaic website:

- Core Principles of Change

- A Sequence for Planning Implementation