Chapter 2 – Identify the Important Problem

Learning Goals

Use these learning goals to focus your attention, connect new ideas to your own context, and identify practical ways to apply what you learn. In this chapter you can:

- Utilise systems thinking to understand complex problems

- Clarify the important problem

- Describe and quantify current practice

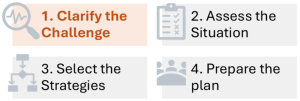

Clarify the Challenge

Welcome to the first of 2 chapters designed to help you clarify the challenge, which will form the core of your implementation plan. The focus of this chapter is to define the real problem and understand why it matters.

Every improvement effort begins with a recognition that something needs to change. But identifying what needs to change, and why, is not always straightforward. In fact, many implementation efforts stall or lose impact because the underlying problem is poorly defined, misaligned with organisational priorities, or lacks urgency. The first step in effective implementation is to clarify the problem.

In busy clinical environments, problems may present as symptoms, like missed targets, cost blowouts, frustrated staff, or unexplained variations in care. However, these surface signals are rarely the full story. It takes time and curiosity to explore the issues around the symptom/s. Beware the temptation to solve the problem as you go. Traditionally, expert and powerful leaders have been recognised for solving problems quickly. This can work well in predictable situations. However, in increasingly complex situations, top-down solutions are rarely sustained. It pays to gain a deeper understanding of the problem within the complex system before you address it.

Describe systems thinking

Systems thinking is an approach to problem-solving that views any issue as part of a larger, interconnected system. At their most basic, systems include elements, connections between elements, and a boundary that establishes what is inside a system and what is outside. The elements within the system interact with each other and are also influenced by outside factors.

Within healthcare systems, there are many different elements, including services, structures, processes and resources, that are connected by people working with and influencing each other. Healthcare systems are often bounded by organisational structures.

Complex Systems

Healthcare today includes multiple complex systems. For clinicians, this is often intuitive. Every patient presents with multiple conditions, social factors, and preferences. For people who have multiple and chronic illnesses, treating one condition may impact others.

However, complexity also exists within the broader systems, around the way healthcare services are delivered. Every clinical decision is influenced by clinical guidelines, team dynamics, time pressures, and organisational priorities.

Complexity is more than just being very complicated. It refers to the ways that interconnected systems function. Complex systems cannot be controlled. Their elements are not independent, and what happens in one part of a system affects others. Relationships influence these actions and largely determine how information is shared (or withheld). As a consequence, every change creates ripple effects and patterns emerge from common pathways and interactions.

Wicked problems are often described within complex healthcare systems, where there are many interacting factors, conflicting values and interests. Often, there is no definitive solution, and as some issues are addressed, new challenges emerge. Managing chronic diseases, introducing medical record systems and reducing hospital readmissions are often referred to as wicked problems. Over time, systems are generally adaptive, and workarounds and solutions emerge from within. While individuals can influence these patterns, there are often both expected and unexpected outcomes.

Using systems thinking to navigate complexity

Systems thinking helps to make sense of this complexity by looking beyond the individual patient and problem to understand the patterns shaping practice. Different patterns of interaction are influenced by the way relationships play out across structures and services. In complex systems, relationships connect the elements and shape how they function. The following table highlights ways in which relationships function within complex healthcare systems.

|

Relationships can… |

This means… |

A clinical example |

|

Create interdependence |

What happens in one part of the system affects others, in both predictable and unpredictable ways |

A change in discharge planning can have widespread effects, including patient flow, staff workload, patient satisfaction, and readmission rates. |

|

Shape information flow |

Relationships determine how information is shared and withheld. |

When a clinician listens to a dissatisfied patient, they need clear processes and leadership support to share this information. |

|

Create habits and routines |

Over time, repeated interactions create habits, routines and workarounds. |

Informal ways of getting things done can either support or undermine formal processes. |

|

Mediate power and influence |

Who talks to whom, who listens, and who has authority, all flow through relationships. |

A trusted clinician champion can influence uptake of a new practice more effectively than a top-down directive. |

|

Enable or constrain adaptation |

Strong relationship patterns create resilience and enable adaptation to unexpected events. |

In an emergency, interdependent relationships can work proactively within the system to allow good ideas and solutions to emerge. |

Clarify the Important Problem

In complex healthcare systems, problems rarely have a single cause or a single solution. What one group sees as a priority, another may experience very differently. Systems thinking helps us recognise that what appears to be the problem is often a reflection of deeper patterns, relationships, and structures. That’s why it’s essential to look beyond surface symptoms and consider the system as a whole when clarifying the issue that truly needs attention.

Reflection Point

This and the following chapter will encourage you to clarify the challenge in a broad sense. Then, the following two chapters will focus on evaluating the context of your organisation and the people you work with. This may feel a little repetitive and painstakingly slow, but it provides a comprehensive investigation. In reality, only a few strategies may be used. Further, while there is a logical sequence across this and the next three chapters, these functions often occur together.

Consider different perspectives

First, consider the important problem from different perspectives. In a dynamic system, no one person or group can see the full picture. Patients, clinicians, managers, and policymakers all see the issue from different perspectives. Actively seek this diversity and discuss comparative needs and expectations to better understand the true nature of the problem. Look for hidden dynamics and points of friction or opportunity that might otherwise be missed.

Look for the bigger picture of the problem

Consider how the problem fits into the processes of delivering care, and where possible, identify who may be affected. Try to define this issue in practical terms, around what is happening (or not happening). Ascertain when and where it is happening, and whether it is a regular or occasional event.

Broad brainstorming here is sufficient, and as you start getting consistent information, you know you are clarifying your problem.

Look for tension for change

Systems naturally settle into a state of equilibrium, even when it’s not optimal. For change to occur, there must be tension strong enough to disrupt the current state. Often problems are framed as an inefficiency, delay or wastage. Sometimes, unexplained variations are highlighted as equity issues. Tension for change can also be fuelled by positive issues, such as a new clinical guideline, an innovative product or a funding opportunity. Clarifying the desire for improvement helps distinguish between problems that are frustrating and those that are worth investing in.

These problematic issues can be disruptive as people create tension for improvement. Sometimes, when this is generated from informal conversations and interactions within the system, leaders may perceive this as conflictual. Therefore, it can be important to name this tension, and recognise its potential as a leverage point, rather than something to ignore or avoid.

Confirm broad alignment for change

It is equally important to align the problem with broader clinical, organisational, and strategic goals. In complex systems, action without alignment often leads to resistance, fragmentation, or stagnation. Identifying how addressing the problem aligns with organisational priorities, professional values, and/or patient needs can be helpful. Connecting the dots between actual experiences, operational pressures, and system-wide goals, helps align individuals towards a proposed benefit.

A problem that matters to frontline staff but is disconnected from leadership priorities is less likely to attract sustained support. Conversely, if the problem is too abstract or top-down, it may be dismissed as irrelevant by those delivering care.

Anticipate side effects and unintended consequences

When planning an improvement, it’s easy to focus on the intended benefits. In complex systems, every change creates expected and unexpected ripple effects. Therefore, it is important to anticipate both and consider that practical routines are likely to be impacted. Talking with colleagues from different roles and walking through a few “what-if” scenarios can help reveal unintended consequences early, so you can plan for them.

The following table summarises these strategies and offers enquiring questions to adapt and use in your local context. Use these to reflect and discuss with your peers.

| Strategy | Description | Enquiring Questions |

|

See multiple perspectives of the issue

|

Ask questions and discuss the issue with a diverse range of colleagues and patients to gather perspectives about the problem. |

Why is this issue important? How does it affect your work? What would you like to see happen? |

|

Look for the bigger picture of the problem |

Look beyond the problem to explore the broader context. |

What is contributing to this? Why is this happening? Who is impacted? |

|

Look for tension for change |

Explore how intentions to do something better emerge from interactions within the system. |

Who wants to do what differently? What is the likely benefit? |

|

Confirm broad alignment for change |

Clarify how the problem aligns with organisational priorities, professional values, and/or patient needs. |

Why is this problem important now? How will it benefit patients? |

|

Anticipate side effects and unintended consequences |

Anticipate how a change might shift workloads, disrupt routines, or interact with other initiatives already underway. |

What else might happen? What will be disrupted? Is this more important that other projects? |

Describe and Quantify Current Practice

While looking forward, it is equally important to take a critical look at what is happening around you. Take time to take stock of what’s actually happening right now. Describing current practice helps surface variation, clarify routines, and reveal patterns that may be sustaining the problem. It provides a concrete starting point and ensures that any change is grounded. Ensure you see the system clearly before you try to shift it.

A deep understanding and set of measurements of current practice is important to create a baseline for change. Look for locally collected data that describes current practice, in relation to the challenging issue. Ideally, look for regular performance metrics that are routinely collected. Also, look for recent audit reports or feedback surveys. In situations where there is no baseline data, it may be important to collect data to really describe what is happening before you proceed. Purposeful audits and benchmarking projects may be necessary to justify the need for change.

Reframe the problem

Once you’ve taken time to observe and describe what’s actually happening, you’re in a stronger position to frame the problem with clarity and credibility. This isn’t about identifying fault or finding the cause of the problem. It is about understanding the system as it is. Framing the problem in relation to current practice allows you to highlight the gap between what is and what could be. It creates a shared starting point for others to engage with the issue and lays the foundation for action.

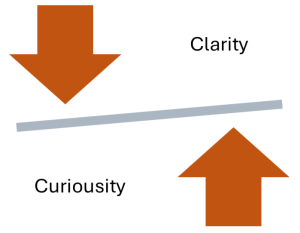

Navigate the paradox Between Clarity and Curiosity

Clarity is essential for progress, but in complex systems, no single perspective can capture the full story. While defining the problem guides focus and builds urgency, different groups often hold different perspectives. Your level of clarity of the presenting challenge will likely change as you make progress. What feels clear in one part of the system may be murky, or even invisible, in another.

Here is a common paradox for implementation: the need to clarify the problem to mobilise change, while also staying curious about alternative perspectives and deeper issues.

Here is a common paradox for implementation: the need to clarify the problem to mobilise change, while also staying curious about alternative perspectives and deeper issues.

If we define the problem too early, we risk overlooking critical insights or dynamics that emerge. BUT, if we remain continuously curious, we may stall or drift without direction.

To navigate between clarity and curiosity, frame the issue sufficiently to guide action, but keep open as new perspectives and data emerge.

Case Scenario – “We Thought It Was Just About Referrals”

Setting:

A regional allied health department, providing inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation services.

Challenge:

Managers identified what seemed like a clear problem: patients referred for outpatient therapy were experiencing long wait times. They framed the issue as inefficient referral and introduced a new digital intake and prioritisation tool. An innovative health tech company provided evidence that they had successfully utilised this digital tool in another similar service.

Initial Action:

A manager designed a new referral workflow with the health tech company, based on workflows and data from the other service. Allied health professionals were trained to use the revised intake process, and timelines were established. However, despite initial buy-in and improvement, wait times continued to grow, and staff reported increased frustration.

Emerging Tension:

The team encountered the Clarity vs. Curiosity paradox.

In their eagerness to fix the problem, they had focused on a narrow problem definition, referral inefficiency, and missed deeper system issues. Informal conversations revealed that the “waitlist” problem was also about variable staffing, unclear communication with local General Practitioners, and patients being referred for services not aligned with their expertise.

Staff perspectives about the waitlist problem were not captured during the initial scoping. Many had not even heard about the new digital intake and prioritisation tool and were uncertain about its abilities to handle the complicated patients they were treating.

Turning Point:

The manager paused the rollout and reframed the approach. A working group was formed that included clinicians, admin staff, and patients, to better understand the waitlist problem.

Reflection Questions

- Are you defining your problem too quickly?

- What voices might help you better define the issue?

Key Takeaways

1. Systems thinking helps clarify problems in complex health systems.

Systems thinking helps make sense of complexity by revealing how people interact across different structures and processes, so it becomes clear where change is most needed.

2. Define the right problem as a critical first step.

Focus on what really matters to patients, clinicians, and the organisation, not just what’s easiest to fix.

3. Understand and describe current practice.

Use data, observation, and local insights to describe and quantify a clear starting point, in order to target meaningful gaps and measure real progress.

Additional Resources & Templates

Understanding Complexity in Healthcare

This white paper is prepared by key Australian thought leaders to simplify complex science for clinicians. It offers a contemporary deep dive into complexity science.

Describing wicked problems in Healthcare

This editorial describes wicked problems in nursing practice and highlights other articles available for download.

Understanding Implementation Science

- Wilson P, Kislov R. Implementation Science. Cambridge University Press; 2022.

Cambridge University Press has created a series of publications, called Cambridge Elements, that provide a comprehensive and authoritative set of overviews of different improvement approaches being used in healthcare. They invite key authors to explore their historical development, examine the research evidence, and identify areas of debate. Generally, they offer a more readable description of key academic discourse, in open access documents.

Review the first 10 pages to inform yourself of the history and purpose of Implementation Science.

- Video: What is Implementation Science? This 2-minute video has been prepared by the Sydney Health Partners to explain how research is translated into practice.

Understanding implementation in innovation

This short editorial highlights the value of implementation for health technology research and practice.

Available Templates

Access the templates on the author’s From Research to Reality webpage on the Mosaic website:

- Using Systems Thinking to Navigate Complexity

A way of understanding how elements within a system interact, influence each other, and produce patterns of behaviour through dynamic interactions.