Chapter 10 – Embed and Sustain Improvement

Learning Goals

Use these learning goals to focus your attention, connect new ideas to your own context, and identify practical ways to apply what you learn. In this chapter you can:

- Sustain improvement in routine operations

- Spread successful change

- Navigate tensions in complex systems.

Implementation is not complete when a change is introduced. It requires the improvement to become part of normal practice. Change that matters is change that lasts.

This chapter explores what it takes to embed and sustain improvement over time, within dynamic healthcare systems. It is built on the sequence of thoughtful planning introduced in this book.

Future paths following successful implementation

Following the successful implementation, there are three likely pathways for improvement in healthcare. The path of Sustainabilitydescribes how change is maintained in the setting where it was first introduced. A second path is spread, which describes how the improvement naturally diffuses into similar settings. A third path of scale-up describes the deliberate expansion of the improvement to reach new sites, populations, or systems.

What is sustainability?

Sustainability in implementation is described as the continued use of new practices or processes in regular practice. For many implementation projects, there is an implementation phase, after planning, that actually introduces implementation strategies into the workplace. Consequently, there is often a later time, at which this implementation support is withdrawn, and it is expected that the change will continue.

The extent to which this happens is broadly described as sustainability. However, if the alignment with system priorities, workflow, and culture is carefully planned, as recommended in this book, improvement is more likely to be sustained within usual practice.

Is sustainability possible?

Five key components of implementation planning are essential for sustaining practice improvement.

1. Continue the change in practice

Throughout the implementation process, there has been an emphasis on specifying what needs to change, when, and where. To sustain this change, it is important to be able to name the procedure, practice, and/or process that changed, and to describe the benefit.

2. Identify key implementation strategies

Implementation strategies were designed to support the change by addressing key barriers and leveraging enablers in the specific organisational context. To sustain this change, identify which implementation strategies were most successful and explain how the key mechanisms of change enable this.

3. Monitor and maintain outcomes

The importance of monitoring and measuring effectiveness and implementation outcomes has been emphasised. To sustain change, continue to monitor and measure key outcomes.

4. Make adaptations

Throughout the process of implementation, adaptations were required when feedback indicated that implementation strategies were not working as expected. To sustain change, it may be necessary to make adaptations to the way the intervention and implementation strategies are delivered, as staff, processes and priorities change. Ensure any adaptations are consistent with the underlying mechanisms of change.

5. Navigate complex organisational contexts

Even when behaviour change has been embedded in routine practice, it can easily be eroded by unexpected disruptions, staff changes and changing organisational priorities. To sustain change, continue to use systems thinking to make sense of and navigate through organisational complexity.

While there is an increasing amount of research about planning and initial evaluation of implementation projects, the longer-term sustainability of change is not yet well understood or reported. Given the inherent complexity within health systems and the dynamic nature of most change, traditional research designs cannot really address two changing sets of circumstances. However, there are studies that look back at implementation projects and can distinguish between those that were able to be sustained, compared to those that were not.

What we do know is that continuing support for the use of implementation strategies is vital. The use of multiple theory-based implementation strategies that address a range of barriers for an individual’s capability, opportunity and motivation to change is important. Strong leadership engagement, continuous monitoring and active stakeholder engagement ensure that implementation strategies can be continually adapted to changing organisational contexts.

Common challenging workplace issues, such as staff turnover and changing work roles and priorities, require sustained leadership support and ongoing opportunities for learning and practice. Therefore, the logic or theoretical matching behind the choice of implementation strategies is vital. Further, this needs to be clearly documented to maintain the fidelity of the change.

Further, ongoing monitoring and feedback loops to identify slippage and reinforce desired behaviours are crucial. Using feedback to make iterative adaptations is key to maintaining improvement and responding to emerging barriers. Therefore, these key principles of effective sustainability have guided the entire sequence of this book. When implementation is carefully planned, the required changes are more likely to be able to be sustained over time.

A Sequence for Action

Many implementation guides approach sustainability as something to focus on after the change has occurred. But in reality, the foundations of sustainability are laid much earlier, during planning.

This book has described implementation as a process of learning and adaptation. If planning is undertaken with genuine attention to relationships, system dynamics, behavioural determinants, and contextual constraints, then the improvement is easier to embed and more likely to take be sustained.

The full implementation sequence is summarised here to demonstrate how key actions contribute to long-term sustainability.

The implementation sequence

Clarifying the challenge ensures the change is anchored in a meaningful and shared problem, increasing its relevance and perceived value over time.

Assessing the situation helps identify the contextual factors and behavioural patterns that will continue to shape success long after the initial effort.

Selecting implementation strategies that are grounded in evidence and aligned with specific barriers and enablers, builds ownership and feasibility from the start.

Preparing the plan using project management, flexible logic models, and realistic measures ensures there is a roadmap for continued improvement.

This repeatable and adaptable sequence of actions progresses from recognising an important issue to implementing a responsive, workable plan for improvement in practice, as summarised in the following table.

|

|

Actions |

Guiding Questions |

|

Clarify the Challenge |

Pause to describe and understand the real challenge, and the dynamics within the system surrounding it. Identify a need for change. |

What are we really trying to improve? Why does it matter?

|

|

Assess the Situation |

Observe and discuss with key individuals the behavioural, organisational, and systemic factors around the challenge. Explore how people experience the problem. |

What’s influencing this challenge? Are we ready to act?

|

|

Select the Implementation Strategies |

Select implementation strategies that align mechanisms of change to real barriers and enablers. Plan to support behaviour change within the healthcare organisation. |

What actions are most likely to support meaningful and feasible change? |

|

Prepare the Plan |

Coordinate engaged effort to introduce a plan to monitor and evaluate embedded improvement. Embed continuous reflection and feedback to inform adaptations. |

How will we deliver, evaluate, and adapt the change? |

This sequence is iterative and represents a cycle of sensemaking, learning and action. If implementation planning is completed superficially, as a compliance exercise or checklist, sustainability may be an afterthought. But when it is approached as a deliberate process of system learning and engagement, the plan itself becomes a platform for resilience that creates the scaffolding for improvement to be adapted and sustained over time..

Spread successful change

Spread refers to the replication or informal diffusion of an improvement, often within the same organisation or service network. It occurs when people see the value of the original change and decide to adopt it. Spread often happens through horizontal relationships of peer influence, professional networks and conferences. It is driven by people who understand and appreciate the improvement and trust the original implementation team.

Because it is driven by local enthusiasm, spread can be quick and responsive. Key stakeholders can be directly involved in adapting the original implementation plan and in choosing which implementation strategies to adopt. For example, the implementation strategies that supported the integration of a new digital platform in one clinic or health service may be largely suitable for similar clinics in a neighbouring health service.

This strategy is often used for broad-scale improvements where an enthusiastic service builds the original implementation plan. They develop a range of suitable implementation strategies, which can be shared and adapted across other similar settings. It is a recognised as an efficient change process. However, the pattern of spread can be inconsistent if sites adopt changes in different ways or without adequate support.

Scale up successful change

Scale up refers to the deliberate, planned expansion of an intervention beyond its original site. It usually involves broader system engagement and requires formal leadership and investment. It ensures that many more people can benefit.

When an intervention has proven effective in one context, scale-up involves developing infrastructure, resources, and adaptations to make it feasible across multiple sites or regions. The original implementation plan may need extensive modification. For example, a home-based rehabilitation program that was piloted successfully in one metropolitan hospital might be scaled up to all hospitals across a state, supported by dedicated funding, standardised training for peer facilitators and ongoing evaluation.

Usually, the process of implementation planning needs to be replicated across each site, as there are likely to be different levels of organisational readiness and stakeholder barriers and enablers to change. However, it can be more efficient as there is often consistency in outcome measures and monitoring and evaluation plans.

Core Principles of Change

Throughout this book, one or more of these ten core principles have been highlighted to reflect the complex realities of healthcare improvement. They emphasise that people enact change within their workplace and are shaped by their health systems. Planning change requires genuine curiosity and thoughtful reflection.

| The Ten Core Improvement Principles | |

|---|---|

| Organisational change requires behaviour change | At the heart of every improvement is a shift in what people do. Systems change when behaviours change. |

| Information alone is not enough | Evidence is necessary, but rarely sufficient. Lasting change requires relevant action and engagement. |

| Behaviour is shaped by multiple factors | Individuals can change their behaviour when they have the capabilities, opportunities and motivations to act. |

| Motivation is complex and contextual | Motivation is more than willpower and attitude. It is shaped by habits and emotions, which vary across people, settings, and time. |

| Capability must be enabled | Individuals need time and space to learn and practice to become proficient and confident. |

| Systems shape behaviour | Organisational structures shape individuals’ actions. Supports are necessary to adjust the status quo. |

| People act within relationships | Change is social. Trust, influence, and connection all matter. Engaging the right people is central to implementation. |

| A shared purpose enables change | When people connect their work to a larger purpose, they contribute with greater care and intention. |

| Implementation requires careful planning | Change needs a thoughtful planning process to address barriers, engage stakeholders, and adapt over time. |

| Change needs a thoughtful planning process to address barriers, engage stakeholders, and adapt over time. | Every team, service and context are different. Individual actions and collective alignment are unique to every change. |

These principles help to frame important attitudes around change. When they are embedded in planning, they are more likely to influence the ongoing implementation and sustainability of change.

Navigate tensions in complex change

Throughout this book, each chapter concludes with a paradox as a deliberate means to reflect on the tensions that arise when planning and implementing change in complex healthcare systems. Progress often depends on holding two truths at once and in balancing competing demands, rather than resolving them. Paradoxes illuminate this space and can guide ongoing sustainability.

Identifying common paradoxes emphasises the need for adaptive leadership. An open and learning culture within implementation teams enables individuals to make sense of competing pressures, reflect on their assumptions and perspectives, and remain open to constructive dialogue. They bring together the technical and relation challenges of implementation.

Ten Paradoxes: Holding Tension with Wisdom

In complex health systems, improvement is rarely about choosing between right and wrong. It’s about navigating between two valid, competing truths. The following tables summarise common paradoxes and their insights.

| The Ten Paradoxes | |

|---|---|

| Simplicity vs Complexity | Communicate clearly, while recognising the system’s inherent complexity. |

| Clarity vs Curiousity | Define the problem clearly yet remain open to different perspectives. |

| Rigour vs Relevance | Apply research and evidence with methodological integrity while ensuring plans fit the local context and address real needs. |

| Consensus vs Progress | Balance inclusive engagement with the need to make timely, forward movement. |

| Boundaries vs Interdependencies | Respect organisational roles and structures, while acknowledging how deeply interwoven systems are. |

| Responsibility vs Influence | Recognise the constraints of a system, while building coalitions, testing assumptions and enabling action |

| Fidelity vs Flexibility | Preserve the core components of an intervention while adapting delivery to local conditions. |

| Planning vs Responsiveness | Create detailed plans, while remaining ready to adapt when the system shifts. |

| Structure vs Adaptability | Create robust frameworks that also enable flexibility and adaptability. |

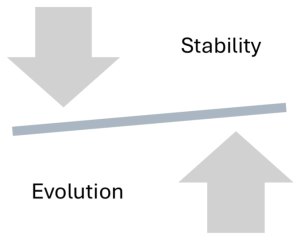

| Stability vs Evolution | Embed change into daily operations while staying responsive to emerging needs and opportunities. |

Each of these paradoxes invites careful reflection to navigate the tensions that define clinical practice. They offer a way of leading implementation in the face of complexity.

Navigate the Paradox Between Stability and Evolution

Embedding change requires consistent and stable routines that deliver benefits reliably. But sustainability also depends on continued learning and growth. Evolution requires ongoing responsiveness to new challenges.

To truly sustain improvement, leaders must let go of the expectation that introduced improvements will remain static. Instead, as systems adapt, improvements need to hold and flex. Implementation plans need to be designed for continuity, and for responsiveness.

The final implementation paradox captures the enduring tension at the heart of sustaining improvement. Often the aim is to formalise and stabilise every improvement.

Yet, health systems do not stand still. Clinical knowledge evolves. Technologies shift. Teams change. Patient needs grow more complex. Priorities shift. New pressures emerge. What was innovative can quickly become outdated, if it cannot adapt.

This final paradox is a call to humility and leadership. The challenge is to keep learning from the plan, even after delivery is complete.

Closing Reflection: Stability vs Evolution

This book closes with the paradox of modern leadership in complex systems, where leaders are responsible for outcomes they cannot fully control. It offers a sustainable way to plan with purpose, explore with humility, and lead with clarity in the face of uncertainty. Implementation fosters a dynamic state of readiness, where people, processes, and systems are improving their capacity to evolve.

In the end, your greatest contribution may not be the change itself, but the conditions you’ve helped to shape. A workplace that reflects, adapts, learns, and grows. A team that is ready to continue the practice of thoughtful, evidence-informed, and human-centred change.

You can help others see the system differently. You can structure action, enable learning, and invite adaptation. So, as you leave these pages, take your plan with you, and also your curiosity. Keep learning. Keep improving. And keep creating systems where better care is always possible.

The most resilient improvements are those that continue to grow, shaped by reflection, feedback, and changing needs. When individuals are supported to learn changes represent improvement over time.

Key Takeaways

1. Sustainability is shaped from the start.

Thoughtful and engaged planning for implementation lays the foundation for lasting change. Embedding improvement into routine systems begins long before the final rollout.

2. Spreading success requires purpose and adaptability.

What works in one setting won’t automatically translate to another. Effective spread balances fidelity to what matters most with flexibility to fit new contexts.

3. Paradoxes are part of navigating complexity in healthcare systems.

Complex change is full of tensions, between two opposing truths. Instead of resolving these, successful leaders learn to navigate them with humility and curiousity.

Additional Resources & Templates

Understanding sustainability in practice

- The following scoping review describes how longer implementation periods, multiple strategies, and behaviour change techniques are key to sustaining clinical behaviour changes in physiotherapists and occupational therapists. Refer to tables 4 and 5 for examples of implementation strategies, categorised using the COM-B model.

- For a more detailed understanding, the following research study examined how the implementation strategy of facilitation was adapted to enhance the sustainability of a collaborative mental health team-based chronic care model.

Available Templates

Access the templates on the author's From Research to Reality webpage on the Mosaic website:

- Core Principles of Change

- Key Paradoxes of Implementation

- Plan for Sustainable Implementation.

Describes the continued use of new practices or processes in regular practice.

Describes the deliberate replication of an intervention in similar contexts, often within the same organisation or service network.

Describes expanding the reach of an intervention to new settings or populations.