Chapter 8 – Prepare the Implementation Plan

Learning Goals

Use these learning goals to focus your attention, connect new ideas to your own context, and identify practical ways to apply what you learn. In this chapter you can:

- Clarify feasible clinical outcomes

- Design implementation outcomes

- Build a logic model.

Prepare the Plan

This is the first of two chapters that bring together behavioural insights, implementation strategies, and an understanding of organisational context into an actionable implementation plan.

The focus of this chapter is to choose clinical and implementation outcomes that are feasible and relevant to detect change, and to embed these within a single page logic model.

Clarify Feasible Clinical Outcomes

To really make a difference, important benefits need to be able to be realised and recognised as improvements.

A critical distinction in implementation is between effectiveness and process outcomes. If a change achieves its clinical benefits, it is seen as effective. Implementation, or process outcomes track and explain why the change did or did not succeed.

- Effectiveness outcomes confirm that the intervention/innovation made a difference

- Implementation outcomes describe how the plan was followed.

Understanding this difference is important, when it comes to explaining what happened.

- A project may have strong evidence but fail to deliver due to poor implementation. Telerehabilitation is an effective alternative to in-person rehabilitation. To experience these benefits, robust and supported technology is required. When technology fails, the benefits of telerehabilitation may not be realised.

- A project may be well implemented but not achieve any benefits because the evidence was never going to be effective. A tomato diet could be clearly explained and supported so that individuals understand and adhere to it, but it is unlikely to demonstrate benefit as the evidence is not there!

Both types of outcomes are essential. The need to have underlying evidence was introduced early, so that there is a real clinical benefit to be achieved. Process outcomes provide early indicators of progress, while effectiveness outcomes are usually measured later to confirm that the expected clinical benefits have been achieved.

Effectiveness outcomes

Defining the expected benefits is usually more straightforward than achieving them. Implementation is reported as effective when an evidence-informed intervention or an innovation is introduced into practice and the expected clinical benefits are realised. Effectiveness outcomes refer to these tangible benefits that often refer to changes in patient outcomes.

Typically, effectiveness is measured in relation to observable benefits in the way individuals (patients and staff) or aspects of the organisation work. These measures are usually identified during evidence selection and refined through stakeholder input. Ideally, effectiveness is measured within the local context.

Implementation outcomes

The process of change to realise these benefits is usually more difficult to describe and measure. Implementation outcomes indicate how well a new practice, intervention, or innovation is being adopted and embedded into a specific setting. They connect the implementation strategies with effectiveness outcomes, in order to understand the success (or not) of the implementation process.

A simple set of comparisons is offered in the following table.

Aspect |

Effectiveness Outcomes |

Implementation Outcomes |

|

Definition |

The intended benefits of introducing research or innovation into practice. |

The results of changing practice to introduce research or innovation. |

|

Focus |

Does it work? |

Can it be adopted, used, and sustained? |

|

Purpose |

Assess whether the change achieves its intended benefit. |

Assess whether the change process was successful. |

|

Typical Measures |

Clinical indicators Health status |

Uptake, adherence, fidelity Acceptability, feasibility |

|

Clinical, Healthcare Examples |

Reduced infection rates Improved function Shorter length of stay |

Adoption of new model of care Acceptability amongst users Staff fidelity to procedures |

|

Timing of Measurement |

Often longer-term, once implementation is complete |

Often measured early and throughout implementation |

|

Why it matters |

Demonstrates the positive impact |

Explains why the change worked (or not), and under what conditions |

Design implementation outcomes

Individuals need to be supported to change key behaviours within their complex organisational systems. Designing bundles of implementation strategies that address behavioural barriers and organisational readiness, has been the focus of the last two chapters. The next challenge is to ensure that these implementation strategies are working.

The Behaviour Change Wheel can assist again. In the previous chapter, key determinants (barriers and enablers) of change have been identified and mapped to the intervention functions. These functions operate through mechanisms of change to produce outcomes.

Mechanisms of change describe the underlying working processes of behaviour change. They describe potential explanatory pathways of behaviour change, and this can be strengthened by the consistent use of theory.

In practice, mechanisms of change are activated when an implementation strategy is utilised. For example, if “lack of knowledge” is the determinant, “education” enables the mechanism of building knowledge, that leads to behaviour change. Education can be delivered in a variety of ways, using different implementation strategies.

The following table demonstrates how determinants describe barriers to change across each of the nine intervention functions, identified in the Behaviour Change Wheel. For each function, mechanisms of change are suggested, together with examples of implementation strategies.

Determinants of Change |

Intervention Function |

Mechanisms of Change |

Implementation Strategies |

|

Poor knowledge, misunderstanding, lack of awareness |

Education |

Increase understanding, correct misconceptions |

Workshops, courses to increase knowledge of why specific change is important |

|

Lack of skill, poor technique or low confidence |

Training |

Enhance ability by developing skills, know-how & confidence |

Practical workshops to learn about & practice specific techniques |

|

Low perceived risk/benefit, ambivalence |

Persuasion |

Alter beliefs & motivate through emotional engagement |

Information and discussion campaigns to emphasise benefits & sway attitudes |

|

Low motivation, absence of rewards, competing priorities |

Incentivisation |

Create expectations by linking positive behaviour to rewards |

Provide recognition, praise & rewards for ideal behaviours |

|

Physical, emotional, social barriers |

Enablement |

Remove obstacles and enhance capacity to act |

Improve access, or provide mentoring & resources |

|

Absence of positive role models |

Modelling |

Demonstrate & support social learning |

Introduce peer & clinical champions |

|

Lack of environment cues or facilitating resources |

Environmental Restructuring |

Alter the physical or social environment to prompt behaviour |

Place signs and use virtual prompts & reminders near desired behaviour |

|

Easy access to undesired options |

Restriction |

Reduce opportunities for undesirable behaviour |

Regulate undesired behaviours |

|

Potential gains from not changing behaviour |

Coercion |

Threats of loss/cost for undesired behaviour |

Fine, penalties, notifications for not changing behaviour |

Therefore, the nine intervention functions of the Behaviour Change Wheel are key to understanding how to measure the progress of implementation strategies. Note how each intervention function targets specific mechanisms of change, that underpin every implementation strategy.

Refine implementation outcomes

Implementation outcomes look beyond whether the intervention “worked” in order to understand how it was received in practice. They describe how well the change process is working by measuring the process of using implementation strategies.

Back in 2011, an international working group of implementation researchers identified the eight most important concepts that were used to measure implementation outcomes. (This paper is in the Reference section of this chapter). In practice, most projects only choose to measure three or four of these outcomes. Discussion with your stakeholders will help to identify which are the most important outcomes to understand how your change worked.

In the early phase of implementation, it is useful to know whether implementation strategies are acceptable, appropriate and/or feasible. Acceptability considers whether people find the change agreeable. Closely related is appropriateness, which evaluates whether the change is perceived as a good fit for the organisation. Feasibility brings in the practical dimension, questioning whether the new procedure is realistic given current staffing levels, workload, and experience. These three implementation outcomes evaluate how the implementation strategies are perceived by the users.

During implementation, it is useful to monitor progress at regular intervals, and to make comparisons between actual progress and the plan. Useful implementation outcomes include adoption, cost and fidelity. Adoption measures the intention to use or the uptake of an implementation strategy. Cost often refers to the time and resources required to introduce the change. Once in place, fidelity examines whether the change is being delivered as intended, and as described in the research evidence. These three implementation outcomes evaluate progress and should be measured at different time periods.

Finally, as change has been implemented, the implementation outcomes of penetration and sustainability are often measured. Penetration is often referred to as reach, as it evaluates how well the change has been integrated into everyday practice. It may evaluate the proportion of eligible patients who are receiving the new service. Over time, sustainability becomes critical, as a measure of what has been continued for six months or more. Often, additional implementation supports have been withdrawn, and this is a measure of whether the change is fully embedded in the service.

Together, these outcomes provide a structured way to assess not just the success of implementation, but its fit in real-world healthcare settings.

Some commonly utilised implementation outcomes are described in the following table.

Example Implementation Outcomes

| Implementation Outcome | Purpose | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Acceptability | Do people find the change agreeable or satisfactory? | Do clinicians feel the new protocol fits their values and workflow? |

| Adoption | Is the intervention or innovation being used or taken up? | How many staff are using the new template or product? |

| Appropriateness | Is the change perceived as a good fit in this organisation? | Do staff report that the change addressed the specific problem? |

| Feasibility | Can the change occur within existing workflows and resources? | Is the new procedure realistic given staffing availability & experience? |

| Fidelity | Is the change being delivered as intended, described in the evidence? | Are clinicians following all steps of the new process? |

| Penetration | How well is the change integrated into normal practice? | What proportion of eligible patients are receiving the new service? |

| Sustainability | Will the change continue over time without extra support? | Is the new checklist still in use after 6 months? |

| Cost | What is the financial impact of making this change? | What are the resource demands to initiate and maintain this change? |

For each implementation strategy, consider what is most important and able to be measured to demonstrate that they are working.

Measure implementation outcomes

Implementation outcomes can be measured using a variety of practical methods, including:

- Surveys & questionnaires: Use relevant validated tools where possible to harness the benefits from previous researchers, and if there are no suitable tools available, create templates to ask staff and patients how acceptable and feasible they find the change.

- Interviews & focus groups: Explore experiences and discuss why or how behaviour has changed.

- Routine data & audits: Track how often the new process is used.

- Behavioural observations: Watch how the change is carried out, record frequencies, or use relevant checklists.

- Routine monitoring: Use existing performance dashboards or regular reports.

Further, measurement strategies can be selected to reflect the intended mechanisms. The following table illustrates how to align measurement strategies with their underlying mechanisms of change, using practical examples.

Intervention Function |

Mechanism of Change |

Implementation strategies |

Measurement Strategies |

|

Education |

Increase knowledge & understanding |

Briefings Workshops |

Pre/post knowledge tests Confidence ratings |

|

Training |

Build physical & psychological skills |

Practice sessions Simulation labs |

Skill assessments Competency checklists |

|

Persuasion |

Alter beliefs & attitudes |

Motivational interviewing Testimonials |

Attitude & belief scales Goals and intentions |

|

Incentivisation |

Create expectation of reward |

Recognition programs Bonuses & awards |

Rates of uptake, adoption Reward & recognition |

|

Enablement |

Remove barriers & increases capacity |

Increase staffing Redesign documents & workflows |

Barrier checklists Log of use of supports Observe workflow changes |

|

Modelling |

Provide demonstration as proof of possibility |

Peer demonstrations Clinical champions Mentoring |

Peer influence observation Diaries of role models, mentors |

|

Environmental Restructuring |

Change the physical or social context |

Modify spaces & routines Adjust roster &, prompts |

Environmental audits Observe adjustments |

|

Restriction |

Limit competing behaviours |

Bans Rules |

Frequency of behaviours Policy adherence |

|

Coercion |

Create expectation of punishment, cost |

Penalties Loss of privileges |

Compliance rates Rates of penalties |

Ongoing stakeholder engagement helps ensure that selected measurement strategies are feasible and relevant for the local context. Whenever possible, leverage existing data sources to reduce duplication and enhance sustainability.

Plan to be responsive

Often, unexpected and unavoidable changes in the healthcare system influence the delivery of implementation strategies. Therefore, it is important to be able to tap into the desired mechanisms of change and look for alternative implementation strategies to support gradual progression.

One of the most tangible tasks in preparing an implementation plan is the creation of a logic model. When clear organisational priorities and unique bundles of implementation strategies are agreed upon by core stakeholders, the critical steps of creating a logic model build consensus and ownership.

Build a Logic Model

Logic models are widely recognised in implementation as visual tools that map relationships between resources, activities, and intended outcomes. They help to visualise the theory of change, by showing how implementation strategies address barriers, utilise key mechanisms and produce change.

Building a logic model requires critical discussion between stakeholders and offers a way to maintain the momentum that was generated as stakeholders agreed on and co-designed implementation strategies, as discussed in the previous chapter. A similar co-design process provides opportunities to test assumptions about what will happen and align actions with outcomes. Practically, the shared purpose for change can be clarified and ways to maintain alignment highlighted.

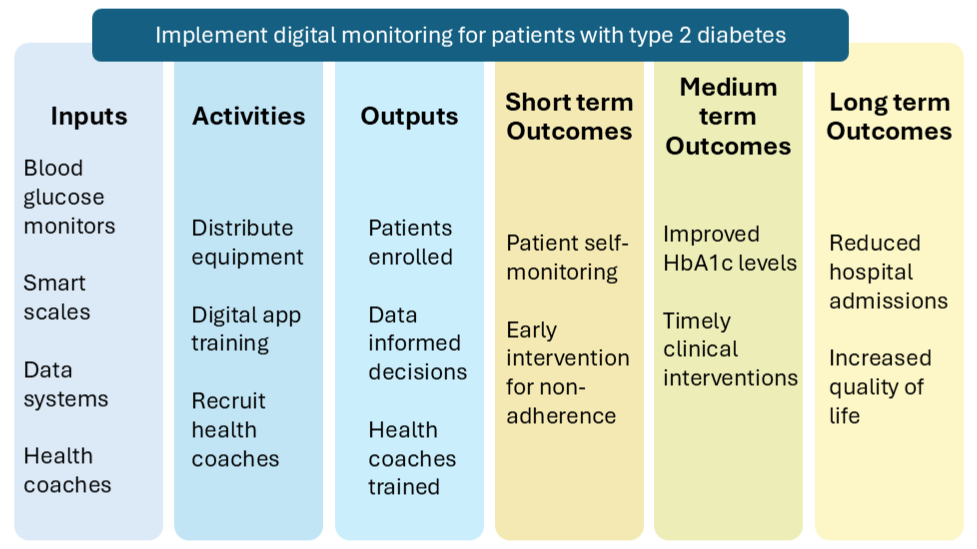

The key components of a logic model guide its creation and integrate the accumulated knowledge and understanding of change. The broad sequence is described, following.

- Identify the change goal, in terms of the desired improvement, practical benefit and importance of action.

- Define inputs in relation to required resources, including people, processes and materials.

- Clarify activities by describing the behaviour changes and the implementation strategies supporting this.

- Describe outputs, which represent the deliverables of each activity.

- Map expected outcomes and organise into short-, medium- and long-term benefits.

- Acknowledge external influences in the broader healthcare ecosystem that may influence how that change will occur

Use this table to help identify each component, in relation to a specific organisation and planned improvement.

Component |

Guiding question |

Examples |

|

Inputs |

What resources are required? |

Staff time, data systems, training materials, technology, materials, partnerships |

|

Activities |

What is changing? |

Service delivery, clinical pathways, documentation, communication, education and training |

|

Outputs |

What will be delivered? |

Number of sessions held, number of tools used, materials distributed, participants reached & engaged, surveys & audits completed |

|

Short-term Outcomes |

What are the early indicators of this change? |

Increased knowledge, confidence, skills Changes in routines Compliance to new processes |

|

Medium- term Outcomes |

What indicates change is happening? |

Adherence to new processes & policies Maintenance of knowledge, confidence & skills Realisation of early benefits |

|

Longer-term Outcomes |

What are the broader benefits? |

Realisation of all expected benefits Addressed the original challenging problem |

Logic models are commonly presented as a pipeline, supporting a practical program aim, as in the diagram below.

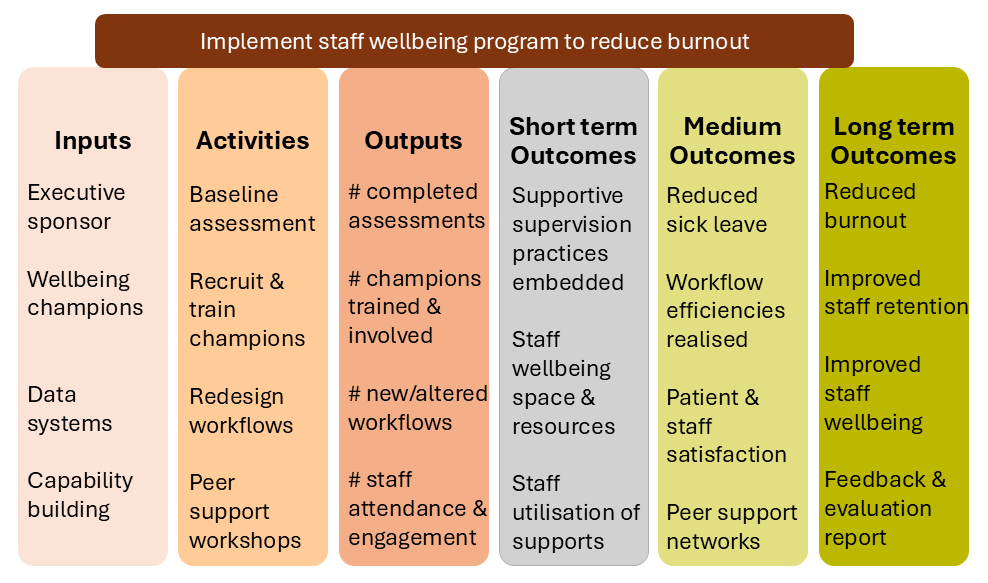

Co-design a logic model

Once all components are clear, map the relationships between inputs, activities, outputs and outcomes. Use arrows or organise the flow within the same row on a chart. Demonstrate how implementation strategies will lead to the sequence of short-, medium- and long-term outcomes. This provides a visual theory of change.

Ensure that outputs (what is delivered) are not confused with outcomes (what changes). Focus on outcomes that are meaningful, observable and practical. Be mindful that many outcomes are beyond individual control. Share drafts with stakeholders to build a shared understanding.

A well-crafted logic model provides a shared reference point. It connects actions with outcomes and explains the theory of how the change is supposed to happen. This makes them ideal for navigating complex healthcare systems and demonstrating the progress of change. They can also form the basis for more detailed evaluation and sustainability plans.

Logic models are flexible tools that can evolve as staff and patient needs change. With clear mapping, they make it easier to see where adjustments are required when circumstances shift. This adaptability allows the model to capture both planned strategies and emerging changes. Another sample logic model is provided with an emphasis on change for healthcare staff.

Chapter nine explores how to track progress, make sense of what unfolds, and adapt to stay responsive in complex systems.

Navigate the Paradox Between Planning and Responsiveness

A thoughtful implementation plan brings structure to improvement. By clarifying outcomes, designing implementation strategies, and mapping activities to results, the conditions for meaningful action are clear.

However, in complex health systems, plans are only ever part of the story.

Real progress requires the ability to notice what emerges and to respond accordingly. The strength of a logic model lies not in its certainty, but in its usefulness as a shared framework for learning.

T

The best plans are living documents that can guide action without constraining it.

Case Scenario: “The Plan Looked Great—Until Reality Hit”

Setting:

A private health network is set to introduce a new remote monitoring program for patients with chronic heart failure.

Challenge:

Often patients with heart failure experience multiple hospital admissions to manage their changing healthcare needs and medication regimes. Research evidence reports that remote patient monitoring, telemonitoring apps, and hybrid clinical support have shown reductions in hospital admissions and improved quality of life for patients with chronic heart disease.

Initial Action:

A cross-functional planning group co-designed a detailed implementation plan, which:

Defined the desired outcome: Fewer readmissions.

Mapped behavioural barriers: Clinician time pressures and low perceived importance of this patient group. Patients’ limited knowledge and awareness of their own heart function.

Included implementation strategies: Clinical champions and efficiency audits for clinicians. Onboarding education and resources for patients.

Included a simplified logic model: Included inputs (home monitoring programs, new workflows), activities (patient education and onboarding, clinical champions, efficiency audits), outputs (completed sessions, audit reports), and outcomes (reduced readmissions, improved patient adherence to home monitoring, improved community acceptance).

This team built workflow charts, onboarding protocols and training sessions. Yet, within weeks of launch, they encountered delays and breakdowns.

Emerging Tension:

This highlighted the Planning vs Responsiveness paradox.

The team had invested in creating a logical implementation plan, but the complexity of care delivery meant the plan couldn’t anticipate every barrier.

Some patients struggled to use the technology. The central nursing team encountered conflict with some GPs who were not fully aware and supportive of the program.

Turning Point:

The project lead responded to the negative feedback and reframed the plan as a “living document. They facilitated regular check-ins with patients, nursing staff and local GPs, to capture real-time insights. With an understanding of the behavioural change mechanisms, the project team was responsive and introduced progressive improvements. For example, onboarding was simplified for digitally inexperienced patients, and nurses co-designed new communication criteria for the local GPs.

Reflection Questions

- How do you balance planning with responsiveness when things change?

- What feedback mechanisms could be introduced to enable more rapid responsiveness?

Key Takeaways

1. Planning needs to account for what success looks like.

Effectiveness and process outcomes shape the vision and experience of potential benefits.

2. Implementation outcomes can influence the process of change.

Clearly defined process outcomes that address key mechanisms of change provide a plan to achieve effectiveness outcomes.

3. Logic models build consensus and visualise a shared roadmap.

Logic models are dynamic and can be updated as internal and external situations change.

Additional Resources & Templates

Understanding Implementation Outcomes

- This seminal academic paper describes the key implementation outcomes used in implementation science research. It identifies effectiveness, service and client outcomes in Figure 1.

Understanding Facilitation

- An extremely comprehensive guide to using facilitation skills to improve healthcare has been developed by the Veteran Affairs Behavioural Quality Enhancement Research Initiative.

Developing a Logic Model

- The following practical guide from NSW Health offers practical information and strategies.

Available Templates

Access the templates on the author's From Research to Reality webpage on the Mosaic website:

- Match Behavioural Determinants & Implementation Strategies

- Choose Strategies to Measure Implementation

- Build a Logic Model

Underlying working processes, pathways, or events that describe how behaviours change

A transparent plan that visualises the theory of change, by showing how implementation strategies address barriers and produce change.