3 Comprehensive search

Philip Worthington

What and why

You are at a new and higher level in your academic study journey now, and this may be the first time you have undertaken an independent research project. This differs from undergraduate research; you need to learn new skills and be more rigorous and systematic in your approach. You need to run your own projects and carry out your own research data collection, carry out interviews or experiments, create code or material artefacts and so on, depending on your discipline.

To demonstrate and present your understanding, you may have to write a single final thesis, which could be 10,000 words up to 100,000 words. Or your course may require you to research and write one or more of these:

- Research essay

- Research report

- Business report

- Literature review

- narrative review

- scoping review

- rapid review

- realist review

- Systematic Literature review

- Case study

- Policy briefing

Examples of policy briefings may be found here:

Searching matters more at this academic level. You need to be able to survey the information landscape and see what is available already written by scholars in the area of your project. It’s not good enough to rely on one database, whatever it is or however good you find it. If you only use one database, you risk not covering your topic sufficiently and missing significant scholarly literature.

Your searching needs to be more thorough , use more than one approach and more than one reputable academic source. You will more than likely be undertaking a literature review, so you need to find the significant scholarly research as it applies to your specific topic. You need to be sure you haven’t missed anything that is central or crucial to your project. Your literature search needs to be reproducible. That is, anyone reading your paper needs to be able to find all the sources that you list. It’s also important for your credibility that you can document the literature search that you carried out, so that other scholars can see the search methods, steps, and sources that you used.

The kind of comprehensive search you do will vary according to the type of research you are doing. If your research is quantitative, your searching will focus on identifying measurable data and statistical information, and you will typically need numerical data, trends, and patterns that can be quantified and analysed statistically. Your search process might involve using databases that provide access to large datasets, surveys, and experiments. If, however, your research is qualitative, your searching would focus on sources which explain the meaning and context of human experiences and behaviours. Searches in qualitative research often involve looking for detailed descriptions, narratives, and case studies. Researchers might use sources such as interviews, focus groups, and ethnographic studies to gather rich, descriptive data. The key to your searching is the need to be systematic and to record your results. Several frameworks guide the searching aspect of academic research, helping researchers systematically and effectively locate relevant literature. These frameworks emphasise structured, strategic approaches to literature searching. They can help you identify areas in which you need to develop your skills and see the bigger picture of how the various research and academic skills interrelate, overlap, and support each other.

Searching frameworks

A searching framework can be useful for structuring your approach to searching. Pick a framework suitable for your research question and field of study. Here are two examples:

PICO Framework (Problem, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome)

The PICO framework is often used in health sciences and other fields involving systematic reviews or clinical questions. It helps researchers structure their search strategy by breaking down the research question into components.

- P: Problem/Population – What population or problem is being studied?

- I: Intervention – What is the intervention being considered?

- C: Comparison – Is there an alternative to compare the intervention against?

- O: Outcome – What are the expected outcomes of the intervention?

This framework helps in constructing clear research questions and translating them into search terms. It is widely used in systematic reviews and evidence-based practice searches in databases like PubMed or Cochrane Library (Huang et al., 2006). PICOS is a modified version of PICO with added qualitative search terms which may be used where time and resources are limited (Methley et al., 2014).

SPICE framework (Setting, Perspective, Intervention, Comparison, Evaluation)

The SPICE framework is an alternative to PICO and used especially in social sciences, where the research is often more qualitative and contextual. It helps in formulating research questions and structuring searches.

- S: Setting – What is the setting or context of the research?

- P: Perspective – Whose perspective is being considered (e.g., stakeholders, users)?

- I: Intervention – What is the intervention or initiative under study?

- C: Comparison – What is being compared to the intervention?

- E: Evaluation – What are the measures of success or impact?

SPICE is particularly useful in interdisciplinary fields where the research context (e.g., education, healthcare, social policy) plays a major role (Booth, 2006).

These frameworks provide structured and systematic methods for conducting literature searches. They will help you to break down your research questions and develop search strategies, and using these frameworks will ensure comprehensive and efficient searching, essential for postgraduate research. Each framework is adaptable to specific fields, from clinical and social sciences to qualitative research.

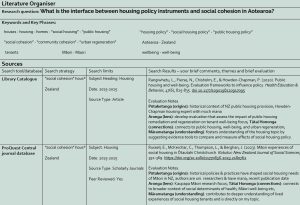

Example using SPICE

Research topic: What is the interface between housing policy instruments and social cohesion in Aotearoa New Zealand?

- S: Setting – What is the setting or context of the research?

- Aotearoa New Zealand

- P: Perspective – Whose perspective is being considered (e.g., stakeholders, users)?

- Policy makers

- Housing Minister

- Cabinet

- MPs

- Government officials

- Homeless people

- Homeowners

- Housing providers

- Policy makers

- I: Intervention – What is the intervention or initiative under study?

- Government policy instruments

- C: Comparison – What is being compared to the intervention?

- Not applicable

- E: Evaluation – What are the measures of success or impact?

- Measures of housing need

- Measures of homeownership

- Measures of homelessness

- Measures of social cohesion

- Other measures of policy effectivness?

How – traditional

The traditional way of searching is tried and true and relies on you being competent at using some specific skills and the advanced features of academic databases. If you are not yet accomplished at these, spend the necessary time and focus on learning and practising them. How and when to apply these is as follows.

An iterative art – not particularly scientific

So, what is searching at this level like? What is the nature or style of it? You might think it is a scientific thing to learn and quite deterministic and sequential. Well, it is not at all. You will need to try things out and see what works and what doesn’t. It’s a process of trial and error, reviewing, revising, tweaking, making some decisions, and trying different approaches, maybe using a different database but always with a critical focus. What is scientific is the need for observation of your results and the database screens. You will do your best searching when you are calm, present, mindful and focused. Set aside a time when you can be in this state of mind.

Key questions

When reviewing your results consider these questions:

- Am I finding the papers I need?

- Do they contribute to answering my research question?

- How do they contribute to answering my research question

Be systematic

Compared to searching at undergraduate level, your searching needs to be systematic, more detailed, and comprehensive, and most likely using more than one source.

Being systematic means:

- Considering all sources relevant to your research question

- Searching each with equal thoroughness

- Applying the same search criteria

- Recording your search strategies and sources in a high level of detail

It may also mean:

- Learning new search techniques

- Using discipline-specific search tools, features, or database fields you have not used before

Record results

Key questions

- How will you know when you have searched all relevant sources?

- How will you know you have been systematic?

- How will you show your supervisor you have searched thoroughly?

Effectively recording search results is crucial to demonstrating a thorough and systematic approach to academic research. To ensure all relevant sources have been searched, begin by documenting your search strategy, including the databases used, search terms, and applied filters. This transparency lets you track gaps or overlaps in your sources and ensures you can replicate your searches if needed. It also allows peer review or critique.

Being systematic requires adopting structured practices like using search logs or tools such as spreadsheets, citation managers, or research notebooks. These should detail each step of your search process, including keywords, Boolean operators, database coverage, and date ranges. This approach helps you evaluate whether your searches align with your research scope and prevents overlooking materials.

Recording results systematically provides a clear, credible foundation for further research.

How you record your searches and results is up to you. These are common ways:

Literature organiser

Why use a Literature Organiser?

A literature organiser document provides a structured way of organising the literature or data you find. Think of the process of using it as a visual display of your research trail, one which helps keep you on the track of your searching plan and focused on your research topic.

Share your literature organiser with a librarian or your supervisor who may offer more focused feedback and suggestions on your progression of thought and discovery of sources and literature themes, assisting you in progressing your research tasks and literature searching.

Formatting a Literature Organiser

There are a variety of ways to arrange your research trail within a literature organiser document. Collate and organise your search strategies and findings in a unique way that best suits you. Some software suggestions for you to use in formatting your organiser document:

- A Word table

- An Excel spreadsheet

- Other tools such as Miro, NVivo and Obsidian

The literature organiser provided here is one approach.

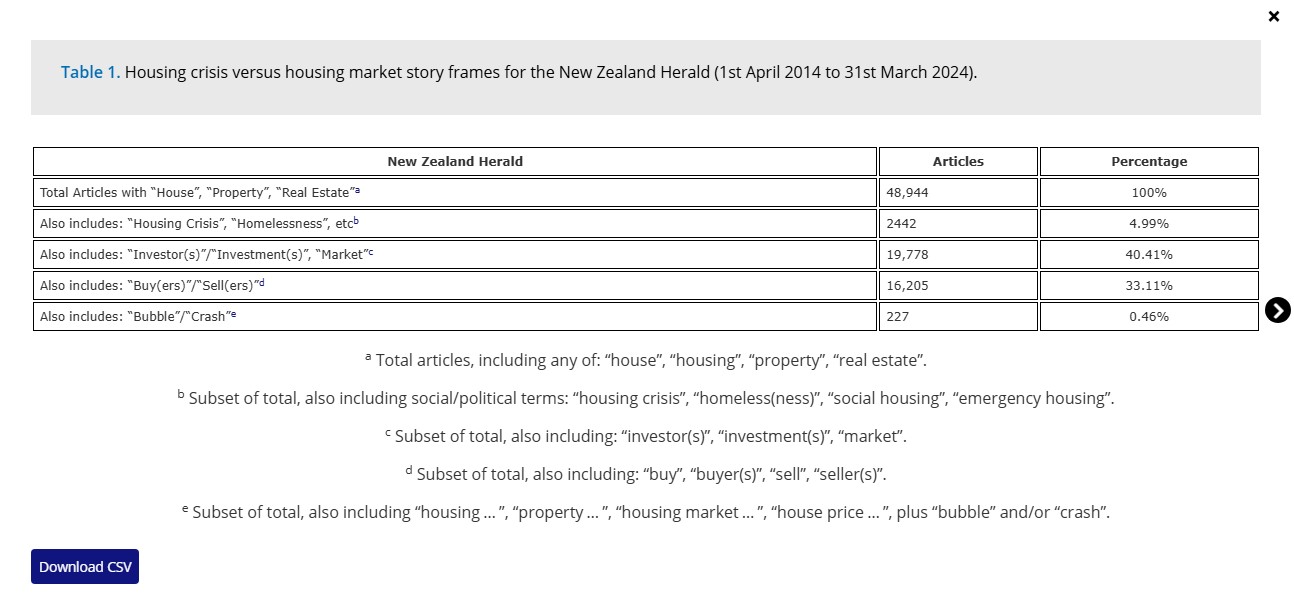

Example

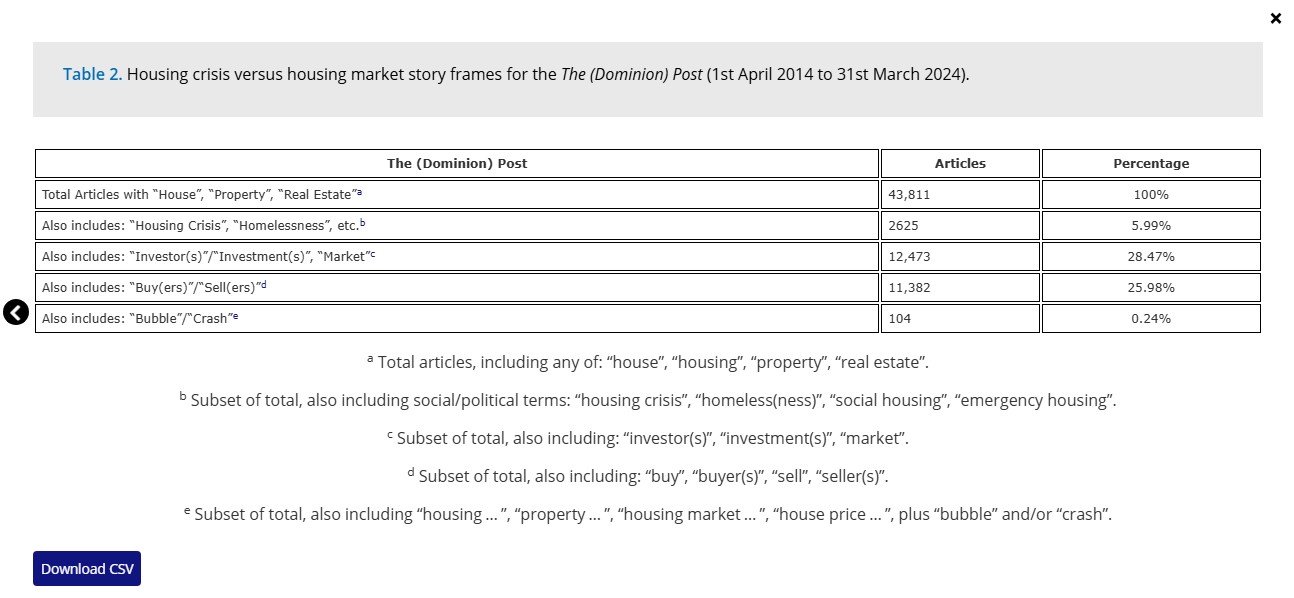

These tables are examples of documenting a comprehensive search in an academic research paper

Source: Davis, A. (2025). Housing news and the enrolment of publics into the asset economy in Aotearoa New Zealand. Journalism Studies, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2025.2547303

Your searching toolkit

All the tools described and demonstrated below make up your traditional searching toolkit.

Keywords, concepts and phrases

Your research question and scoping searching from the previous chapters are your starting point. You have the keywords, concepts and phrases which you have used to scope out the academic literature on your research topic. I recommend laying out your keywords, concepts, and phrases on paper or in a simple online file. This allows you to visually structure and arrange the raw material you will use for your comprehensive search.

Selection of keywords

The keywords you choose to use in a search will make a huge difference to the result. You will already know this from your everyday life and use of Google for online shopping and looking up information. It is just the same when searching for academic literature for a research project. For example, suppose you have a broken shelf in your refrigerator. You might start searching with the keywords “Kelvinator fridge door shelf”, and plenty of results come up, but none quite match your particular fridge. Looking at the first page of results, you notice part numbers and some terminology specific to refrigerator spare parts:

So you modify your search by using part numbers and/or the particular terminology used within the knowledge domain of refrigerator spare parts. You will need to do the same things in your comprehensive research search, except now you have a larger toolkit. All the tools in this section of the book are available for you to use as required for a comprehensive search. By applying your critical thinking skills and knowledge of the subject domain and your research topic, you can select and effectively use the appropriate tools.

Combining search terms

Combining search terms is a fundamental skill in structuring searches. It uses the words AND, OR and NOT to connect search terms. These are called Boolean operators. By using Boolean operators you can broaden your search to find more results or narrow your search to find fewer. Broadening increases your recall, and narrowing increases your precision. If you find you are getting irrelevant results because of one particular term in your search, you can also exclude it by using NOT.

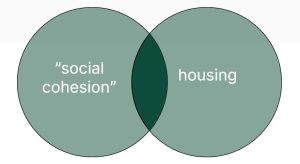

AND: Narrows the search by combining terms (e.g., “social cohesion” AND housing). Both terms must be present. AND is usually the default operator.

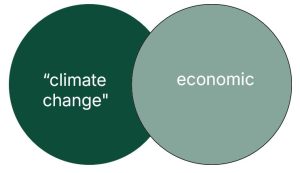

The dark green area shows all the records with both terms.

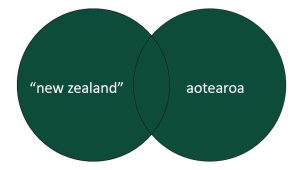

OR: Broadens the search by including synonyms or related terms (e.g., “new zealand” OR “aotearoa”). Only one term need be present for the record to be found.

The dark green area shows all the records with at least one of the terms.

NOT: Excludes unwanted terms (e.g., “climate change” NOT economic”).

The dark green area shows all the records with one term but not the other.

See Keyword or phrase searching for more examples of how to combine search terms.

Truncation

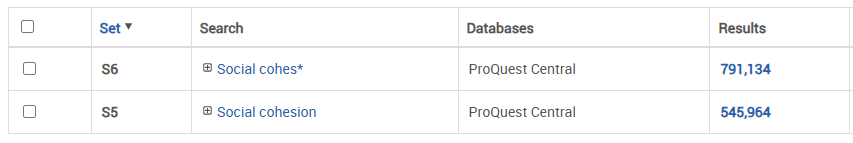

Truncation refers to a way of shortening your search term and allowing the database to search for word variations of the term. This is useful to broaden your search and ensure you do not miss relevant results. Most databases use an asterisk * as a ‘wildcard’ substitution for one or more other letters to do this.

Example:

Social cohes*: captures “social cohesion,” “social cohesive,” “social cohesiveness.”

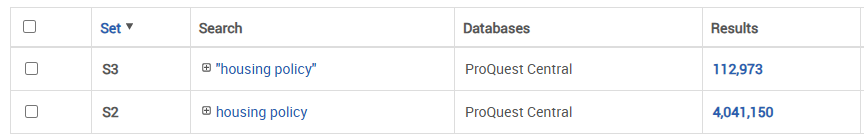

Phrase searching

Phrase searching refers to a way of searching for just the words in a phrase. It is a powerful way to focus a search on a concept. In keyword searching, such as a Google search, you enter keywords. The search engine looks for those keywords wherever they appear in its index and returns the results. Generally, the results are then relevance ranked so the most relevant appear at the top of your search. This is fine for simple searching since it does what you want. For a comprehensive search, though, it can be problematic, and the use of phrase searching will enable you to be more precise and reduce the number of irrelevant results that you would otherwise have to look through.

Example:

Enclose your desired phrase in quotation marks. “Housing policy” finds the exact phrase housing policy, that is, the word “housing” immediately preceding the word “policy”. Do this, and your search will only return records which have the phrase “housing policy”. Without the quote marks, the system will search by default for both housing AND policy.

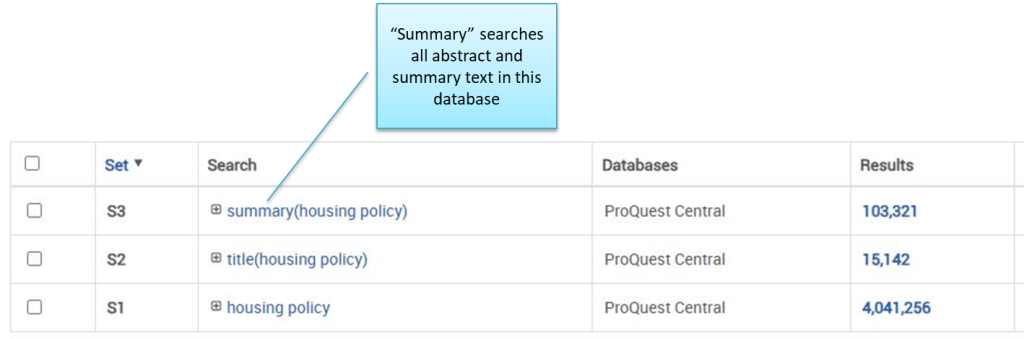

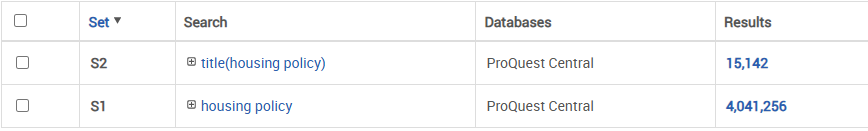

Field searching

Field searching limits where the database searches for your terms within the metadata for the records. Instead of searching for your terms across the whole database, which may include full text, you can limit your search to fields such as Title or Abstract, increasing the relevance and focus of your search. This is a way of narrowing your search.

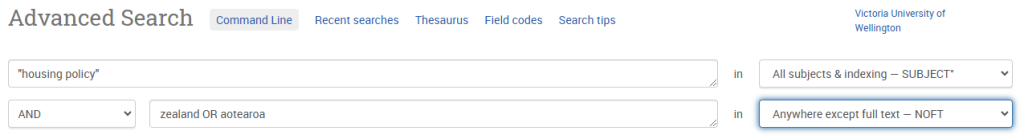

Example:

Limit a search for “housing policy” to the Title field. In this database, this search will be limited to documents that have the words “housing” and “policy” in their title. They are, therefore, likely to be mainly about housing policy. The downside of this approach is that you may miss papers that deal with housing policy yet do not have these precise words in their title, so be cautious when using this approach. I only tend to use it when it is difficult to get a small enough number of results.

The subject of an academic paper tends to be reflected in the title, abstract and descriptor or subject fields, and it is often possible to limit your search to these fields in one search. This is a middle course between limiting to Title and not limiting at all. Learn how to browse the fields for faceted subheadings and gain some familiarity with the restricted vocabulary sets the database uses. This will pay off by enabling more precise searching and is shown below.

Example:

Notice the results numbers:

| Search no. | Search | Limit | Result | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | “housing policy” | Unlimited | 4,041,256 | Rather too many to go through! |

| S2 | “housing policy” | Limited to Title | 15,142 | A reasonable number to start with and further refine the search down |

| S3 | “housing policy” | Limited to Summary | 103,321 | A middle course |

Subject headings

Subject headings are very useful features of many databases. A human being has read an academic paper in a database and decides on its main subjects. They then assign a defined piece of text, usually called a descriptor or subject heading, to that item. The metadata for that item then has additional controlled access points to the subject content of the paper. You, as the searcher, can use these headings to do a specific narrow search looking for that subject content.

- Your research question will cover several concepts

- Your comprehensive search can use subject headings relating to these concepts

- The subject headings can be combined to cover papers relevant to your research question

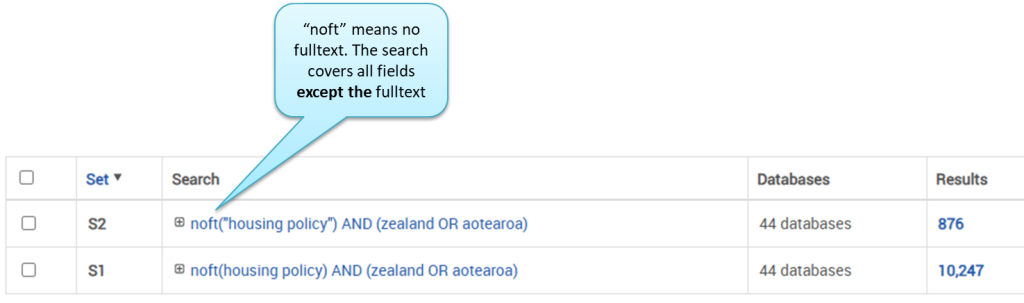

Example: Start with a search that will give you relevant results. This search gives 876 results, and they look relevant:

There are two ways to go now.

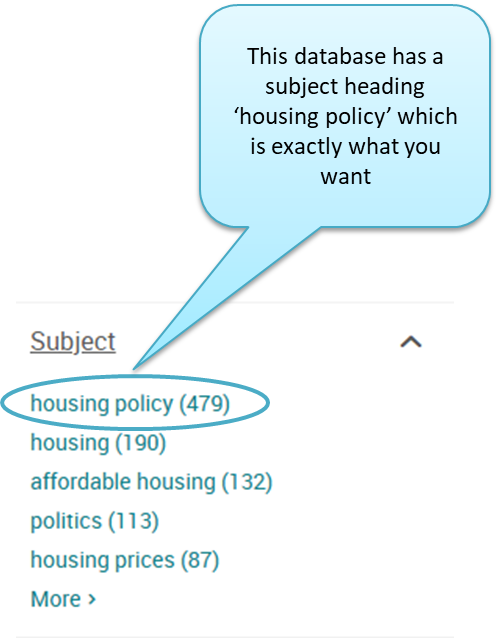

- In the left-hand filters pane, open Subject, by clicking on the down arrow:

Click on ‘housing policy’ now, and you will get back 479 items with ‘housing policy’ as a subject heading combined with the ‘(zealand OR aotearoa)’ part of your search. You have effectively started with a search to identify papers on housing policy in New Zealand/Aotearoa and then refined your search to only those papers which have the subject heading ‘housing policy’. A subject heading may have a sub-heading. For example the Waitaingi Tribunal report Kāinga kore : the stage one report of the Housing policy and services kaupapa inquiry on Māori homelessness, has these subject headings with subdivisions:

Housing policy — New Zealand

Homelessness — New Zealand

Māori (New Zealand people) — Housing — New Zealand

The database also has ‘Location’ as a filter. This is a more precise way of refine your search:

Click ‘New Zealand’ now to filter your search further to only 104 items with ‘housing policy’ as a Subject heading that also have New Zealand as the Location:

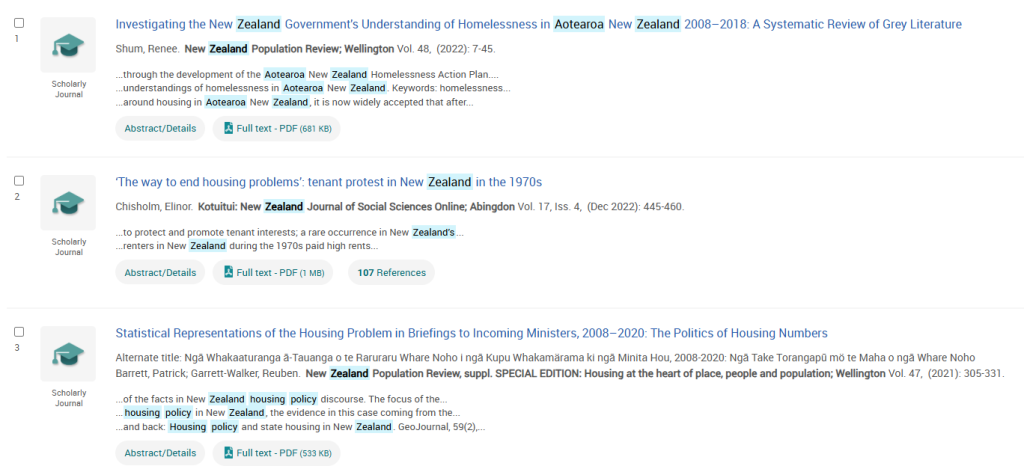

Looking at the first page of the results, this will be a good set to go through one by one and assess for inclusion in a literature review:

2. Alternatively, you can look through the first page or two of the results and critically evaluate them, then:

-

- pick two or three which are the most relevant to your research

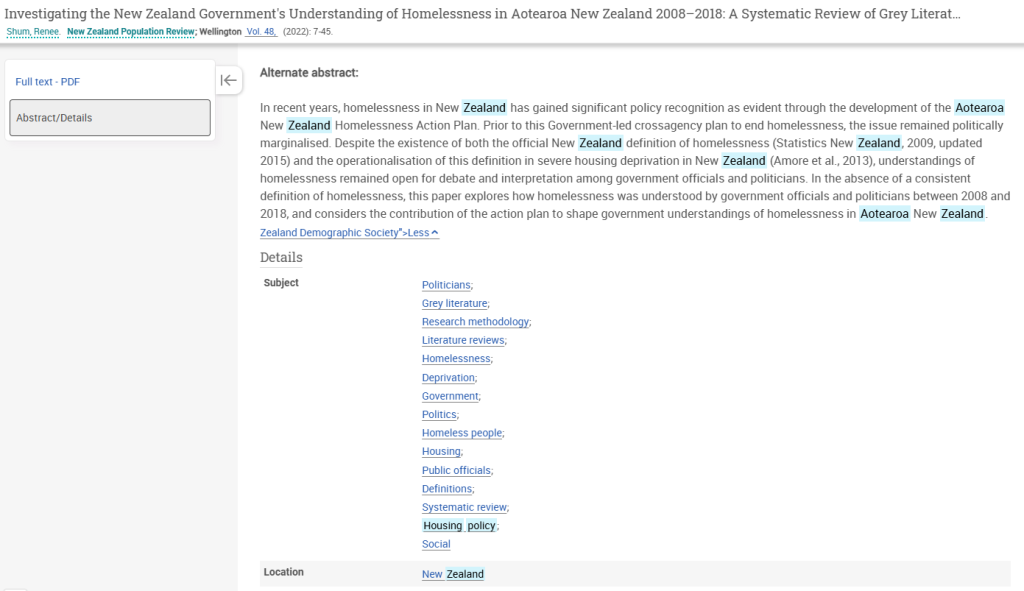

- look at the subject headings in them (click Abstract/Details):

In this case, you discover ‘housing policy’ is a subject heading, and there are others which may be pertinent to your topic, such as ‘homeless people’, ‘housing’ or ‘deprivation’.

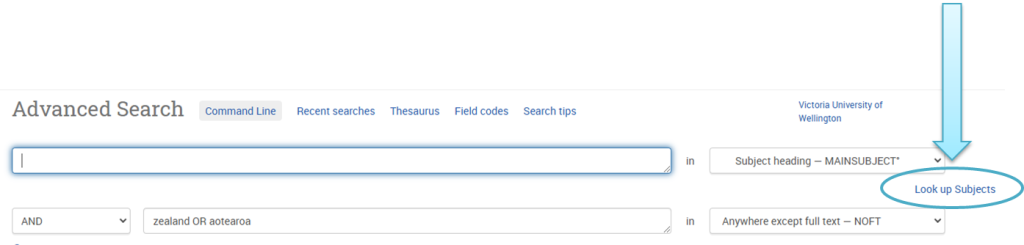

Note: If you click a subject heading from the screen above (a full record), you will lose the other parts of your search. So, it is better to make a note of the subject headings that are relevant and do a new search using the Advanced Search screen

Enter “housing policy” and choose Subject from the field dropdown:

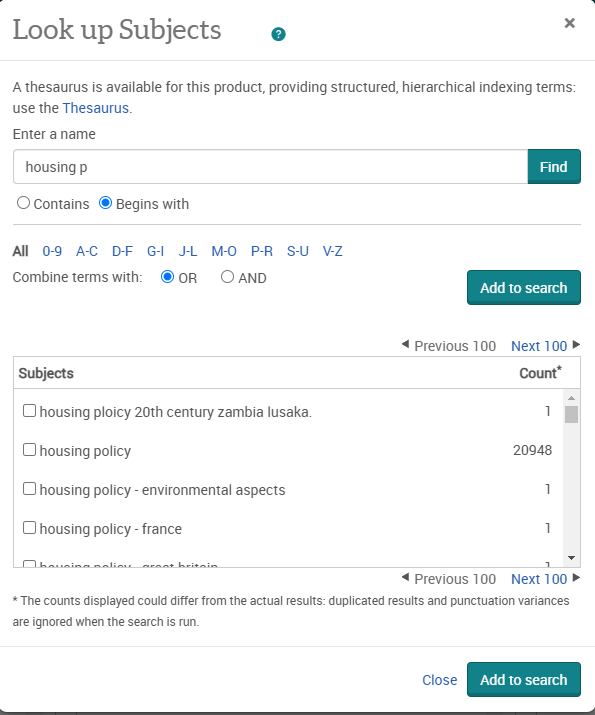

If you choose MAINSUBJECT you can look up Subjects:

Enter the start of the subject and press Find, then click the subject you want and Add to Search:

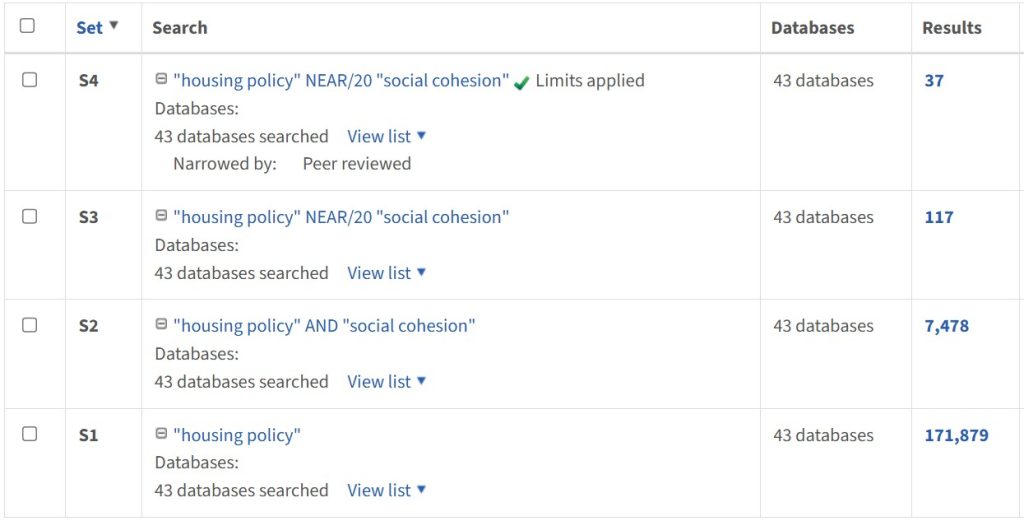

Search history and saving searches

Most academic databases will let you save your searches. This is extremely useful for two reasons. Firstly, if you save your searches, you have a record of the actual searches you used for your literature review. You can cut and paste this information when writing up the literature review’s search section. Secondly, when you are searching, it allows you to look back at the searches you have done in a session and see the number of results found for each search. You can use this to assess the usefulness of that particular search and decide whether or not to persist with it. You can usually click on the search in the search history of the database to rerun the search and review the relevance of the results. Some databases will also allow you to combine two or more searches from your search history in one new search without having to re-enter each one.

Learn how to use the search history to save, modify and repeat searches in the databases you are using – it is a very useful skill at this level.

This is an example of the search history in the ProQuest database:

This database has the NEAR command which lets you specify the number of words between the search terms. In the last search (S4) the phrase “housing policy” must appear within 20 words of the phrase “social cohesion”.

Finding similar or related papers

When you find a research paper which is very significant for your research, you can it to find further papers. There are three similar techniques for this.

Pearl growing

When you read paper you realise this is a pearl and you become aware of concepts, keywords, authors, phrases, ideas or methods, which you then use in further searches.

Cited reference searching

This approach involves tracking the references cited by a specific document (backward citation) or finding newer documents that cite the original document (forward citation). It helps researchers identify connections in the literature, trace the evolution of ideas, or discover new relevant research based on a key paper.

Citation chasing

As the Scoping Search chapter mentions, reading a text’s reference list or bibliography can be an excellent way to find related literature. This process is often called “citation chasing” or “snowballing”, and is particularly useful at the beginning of a new research project since your supervisor or lecturer will normally provide you with several texts as a starting point.

Because citation chasing doesn’t operate using keywords, it has some advantages over traditional keyword searching:

- You don’t need to know what keywords to search for before searching – in fact, citation chasing can be a great way to find out what your topic’s keywords are

- Texts that use synonyms to your search terms will still be found

- Keyword searches can become cluttered by irrelevant topics with keyword crossover; by citation chasing, you’re exploring a a better selection of sources which are directly relevant to your topic

- Occasionally citation chasing will find articles from adjacent topics you weren’t expecting, opening up new research avenues

These advantages make citation chasing a healthy way of diversifying your search strategy, in a similar manner to diversifying your search databases, and protects you from missing important works.

Additional resources

- How do I find information sources? (QUT Study Smart)

- Search techniques: Understanding AND, OR, & NOT (3 min video)

- Assignment research help > Find

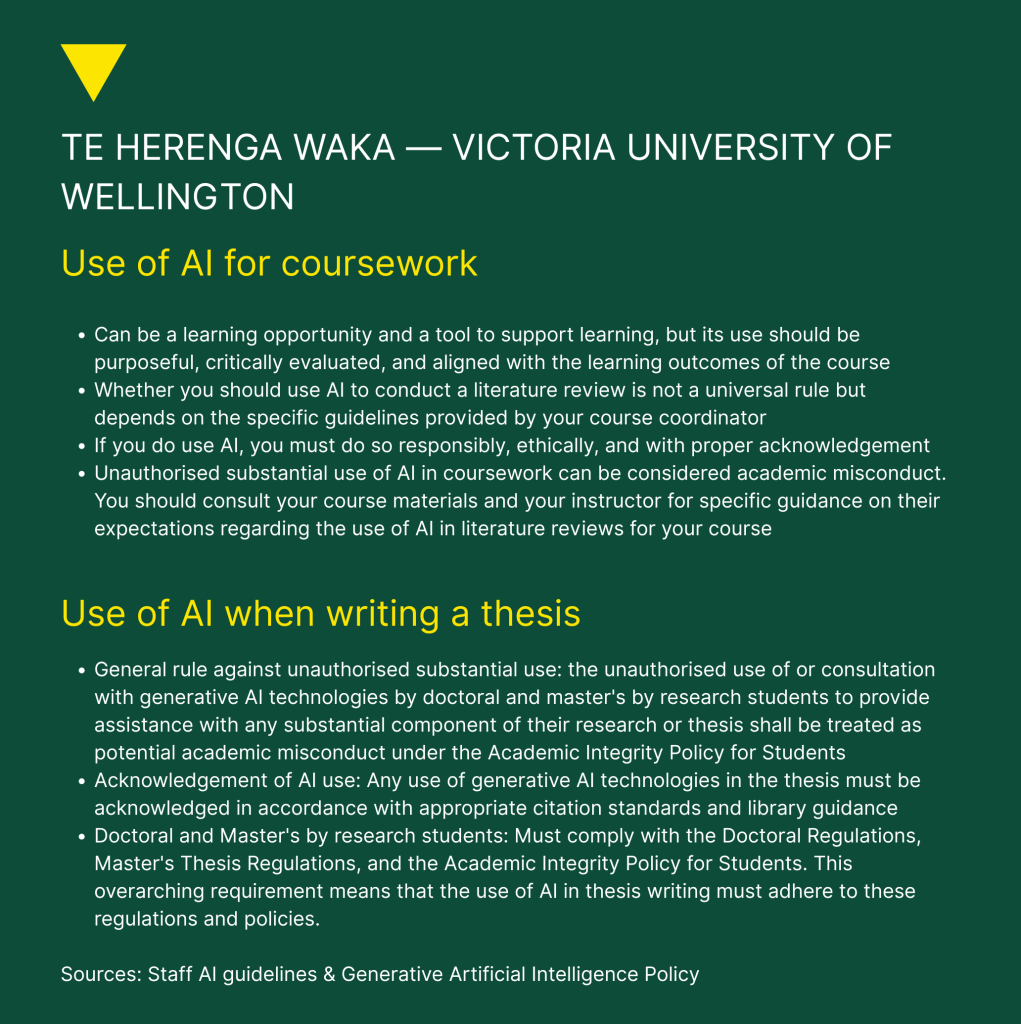

Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington

![]()

Digital Research Tools has information and resources for NVivo and Miro for Research (Access is restricted to current students and staff)

AI tools for comprehensive search

Key Takeaways

- AI is transforming how we interact with information and create new knowledge

- Knowing the landscape you’re working in is critical

- Information literacy and discovery frameworks and values apply more than ever

- Research values and skillsets are more important than ever

- Learn to do it the hard manual way first

There are many generative AI tools that will do a good job of comprehensive searching for a literature review. Indeed, the tools are developing so quickly and improving in such great leaps and bounds that there are almost no parts of the academic research process that can’t be done by them. The growing capability of AI to perform traditional academic tasks means the future of knowledge work and ‘the university’ is changing rapidly. Several questions arise:

- To what degree do you still need to demonstrate research capabilities when you can use AI as a lever for higher-order reasoning?

- Does the growing competence of AI tools demand you prioritise, identify, apply, and extend the kinds of judgment, contextual sensitivity, and ethical reasoning that remain distinctly human?

- Does task completion signal true understanding?

- Is a researcher using AI vulnerable to the “persistent illusion of learning”?

- How does AI reveal its limits[1] and what happens if you don’t understand those limits?

The illusion of learning and unproductive success[2]

If you use an AI tool on a task you have not mastered yourself, you are likely to be giving yourself an “Unproductive success” and subjecting yourself to the illusion of learning. Students who “maximize performance in the shorter term without maximizing learning in the longer term,” are creating “an illusion of learning” (Kapur, 2016). As Wolf (2025) puts it “True beliefs are not the same as understanding”, which is to say that you may have found the right information, answers or facts, but have no or little understanding of their context and how they relate to your prior knowledge.

You don’t understand that you don’t understand. AI can limit your own learning by threatening the retention of knowledge and destroying internal motivation. You may think to yourself “If AI can do it, why do I need to know how?”, and “I can avoid the stress of learning”. With the use of AI, you also face a lack of feedback on your work and the means to check on your understanding, and therefore you can proceed through the research process with a dangerous illusion you are really learning.

Embrace automation?

I say you should never use a generative AI tool for a task or skill that you haven’t first learned yourself the hard traditional way. Imagine you have a meeting with your supervisor and they ask you how the topic analysis for your literature review is going. What do you say?

- Your AI-enabled version of your academic self:

Oh I am finding it brilliantly easy, I got a sub to Consensus/Perplexity/[insert another faourite AI tool], uploaded the papers, let it analyse them and it generated a topic analysis report for me. I’ll paste that in to my thesis today

- The version of yourself enabled through the practice of traditional methods:

I am finding that difficult. Just the sheer amount of reading takes more time than I expected, but I am discovering some new lines of inquiry and modifying my set of topics as I go. Can I show you now?

Who has learnt academic skills?

Generative AI tools are not just a neutral tool or something that can be picked up and put down and they present accuracy and ethical concerns. For information discovery they have limitations in:

- Quality – prone to “hallucination,” generating plausible-sounding but incorrect or fabricated information

- Depth – lack the ability to perform genuine critical thinking, generate truly novel insights, or engage in the nuanced, in-depth analysis and synthesis of information required for original research

- Bias – may reflect or amplify biases present in training data

- Scope – most use only a subset of the world’s academic literature

These limitations affect the ability to provide a complete information picture in any given scenario. Remember generative AI tools are trained to speak plausibly about everything but actually understand nothing.

Opportunities and Challenges

| Research benefits | Research challenges |

|---|---|

|

• Summarisation • Interpretation • Analysis • Visualisation • Mapping • Connections • Reviewing • Gap analysis • Hypothesis • Translation • Workflow |

• Integrity / misuse • Privacy • Legislation • Information bias • Content authenticity • Transparency • Dependence • Implementation • Staff capability • Equity • Relationships • Sovereignty • Cost |

Critical evaluation of AI tools

Critical evaluation skills ensure information is:

- Accurate

- Reliable

- Unbiased

- Relevant for the purpose

“We want our students to develop the higher order skills of being able to critique writing produced by AI chatbots and to direct the outputs of new technologies. But those skills depend on more fundamental skills and there is no way we can jump ahead to the more advanced skills without acquiring the more basic skills first. In order for students to successfully grapple with problems computers cannot do, they must work through problems that computers can do.”

Christodoulou, D. (2023, February 5). If we are setting assessments that a robot can complete, what does that say about our assessments? Medium. https://blog.nomoremarking.com/if-we-are-setting-assessments-that-a-robot-can-complete-what-does-that-say-about-our-assessments-cbc1871f502

AI tools for literature searching

AI tools can be great companions during the literature search process. They are good at quickly finding relevant papers, summarising key ideas, spotting patterns across lots of texts and so on. They can surely save you time—but it’s important to understand they’re there to complement and not replace your thinking, critical reading, and evaluation and synthesis skills. AI tools can vary in quality, reliability and access to academic sources. I believe it is a good practice to explore these tools critically and discuss their use with your supervisory team. This will ensure that any such AI tool you choose will align with the expectations and standards of your field and University. You must always understand your Universitiy’s current policies regarding the use of AI for research.

Examples of AI tools

As your research collection grows, a powerful technique is to cross-reference the reference lists of multiple works to find common ancestors. This kind of investigation is known as “citation network analysis” and is generally quite complicated to conduct manually. Luckily, new software has emerged to help search across the citation network of your area of interest. These tools also provide useful visualisations to help understand the citations between works at a glance.

- Litmaps allows you to explore references and citations using visual “literature maps”. Litmaps supports the cross-referencing of citations, authors, and semantic text content. Its search methods also include advanced options to let you filter citations by keyword, date range, authors, and publication details.

- Connected Papers is a simple tool that creates visual summaries of a single work’s top citations and references.

- Inciteful provides various citation network analysis tools including citation cross-referencing, and a pathfinder to identify citation trails between any two articles.

- ResearchRabbit is a research collection tool that provides a useful interface for citation chasing, but has limited citation network analysis features.

It’s worth noting that some citation chasing software (Litmaps and ResearchRabbit, from above) have additional features that can also improve your research workflow. These can include document storage, ongoing search scanning, and linking with reference managers. It’s worth investigating the full breadth of features available to create a concise research workflow.

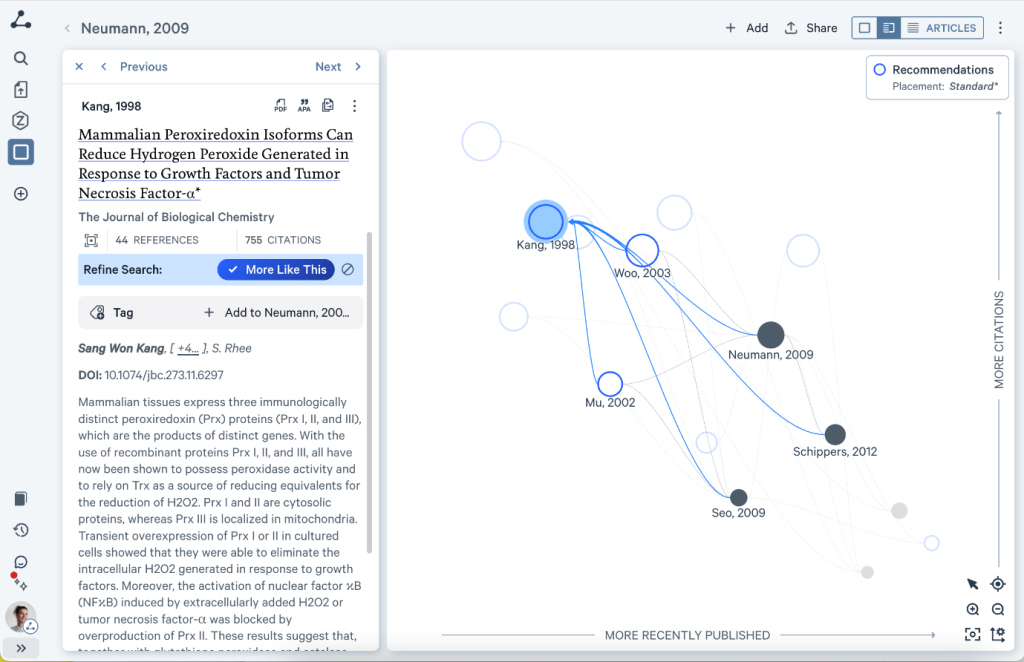

Example Litmaps search: Social cohesion and housing policy in Aotearoa New Zealand

Litmaps offers citation network cross-referencing. Here we can see its recommendations as blue circles, and the way they’re cited by the input works, shown as dark circles.

Let’s work through an example of citation chasing in Litmaps. Citation chasing always begins with a known article, or set of articles. For this example, we’ll start with a single article, and use that as a starting point to gather relevant articles.

First we need to find a starting article. We’ll use the Search page on Litmaps and type in a keyword phrase for our topic, “social cohesion + housing policy in Aotearoa New Zealand”.

Litmaps search for topic, “social cohesion + housing policy in Aotearoa New Zealand”

The top article from Litmaps’ keyword search results seems useful, so we’ll start here. Tip: alternatively we could have brought articles we already know about into Litmaps. We can either search by their title or DOI, or use the Import option in the sidebar to submit a BibTeX file from your reference manager.

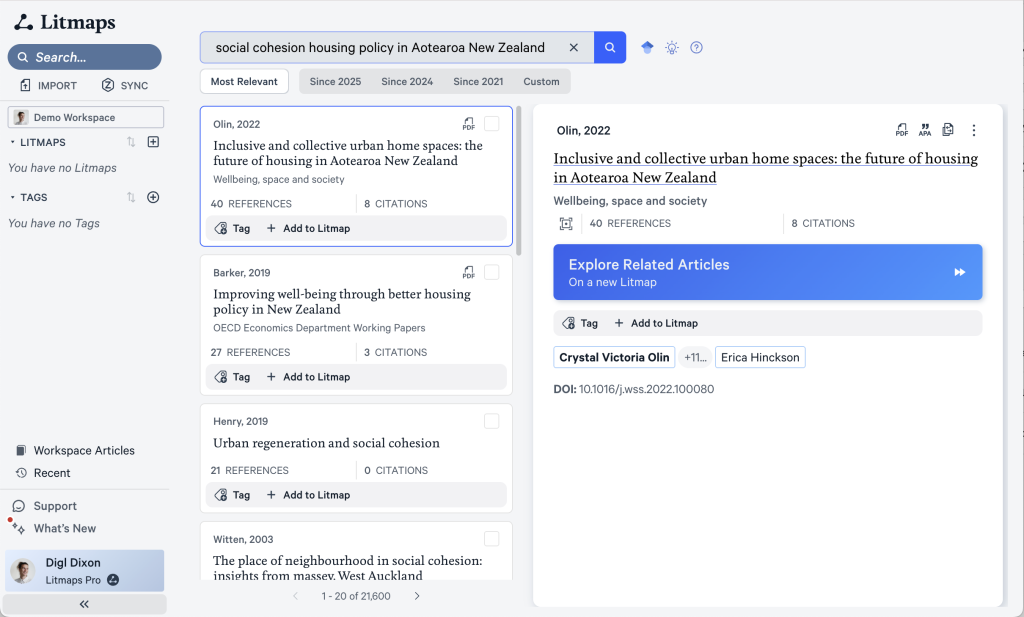

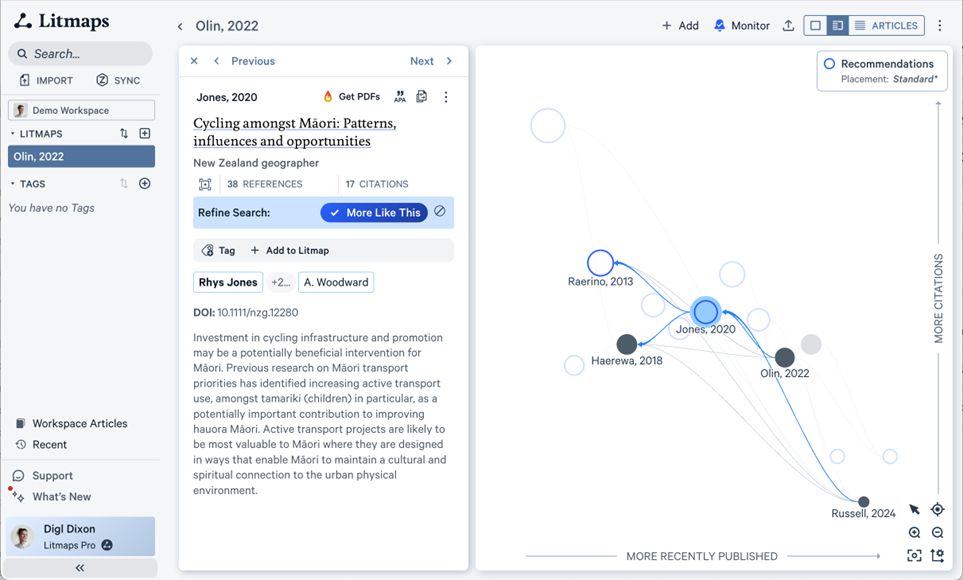

Clicking on the Explore Related Articles button allows us to generate a “Litmap” – a visual representation of articles and their citations and references. Here we can see the article we started with, “Olin, 2022”, coloured in black. Litmaps has scanned its citations and references, and is suggesting the hollow blue articles as the most relevant to your starting article:

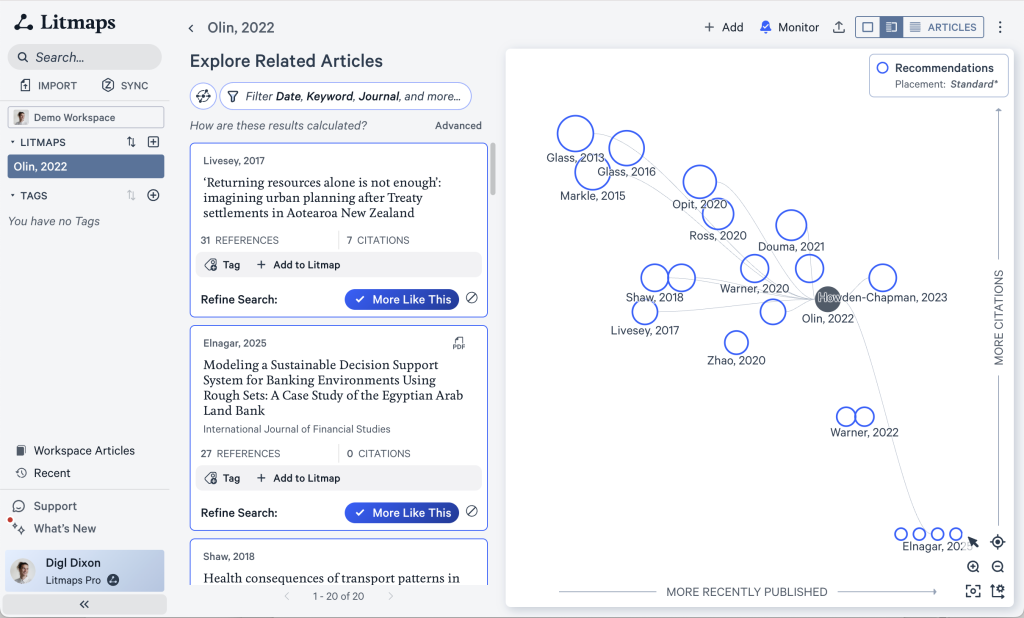

By clicking on the hollow blue articles, or by browsing the list in the sidebar, we can review these articles and assess whether they’re relevant. Above, we’ve found an article on “Shared mobility in a Māori community”. Since we expect this to have some relevance towards our research question, we can click the blue “More Like This” button. This will add the article to our Litmap, and extends the set of citations and references that Litmaps will search over. Here, we’ve clicked “More Like This” on several of Litmaps’ suggestions. You can see these articles have also become coloured black on the Litmap – they’re now added to the Litmap, and will stay here:

You’ll also notice the yellow “New results may be available” banner. Clicking “Refresh” will ask Litmaps to scan the newly-combined references and citations of all of the articles that we’ve added using “More Like This”.

Here is the new set of results. You can see how they’re linked to several of the articles we added to our Litmap: they rank more highly because they’re more interconnected with what we’ve said we’re interested in.

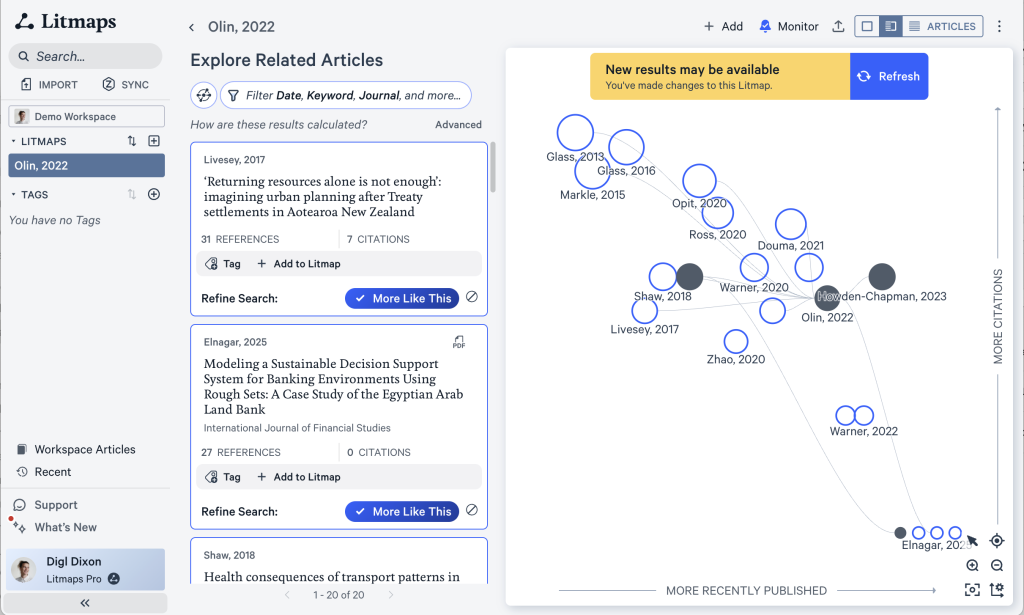

On the Litmap you can visualise how each of the suggestions either cites or references your articles. Clicking or hovering over an article can provide a clearer view:

Here we can see that this paper (“Jones, 2020”) is cited by Russel, 2024, and Olin, 2022. It in turn cites Haerewa, 2018, and Raerino, 2013.

Tip: We can deduce the direction of the citation by looking at the lines’ arrowheads, or inferring it due to the Litmap’s horizontal axis being publication date.

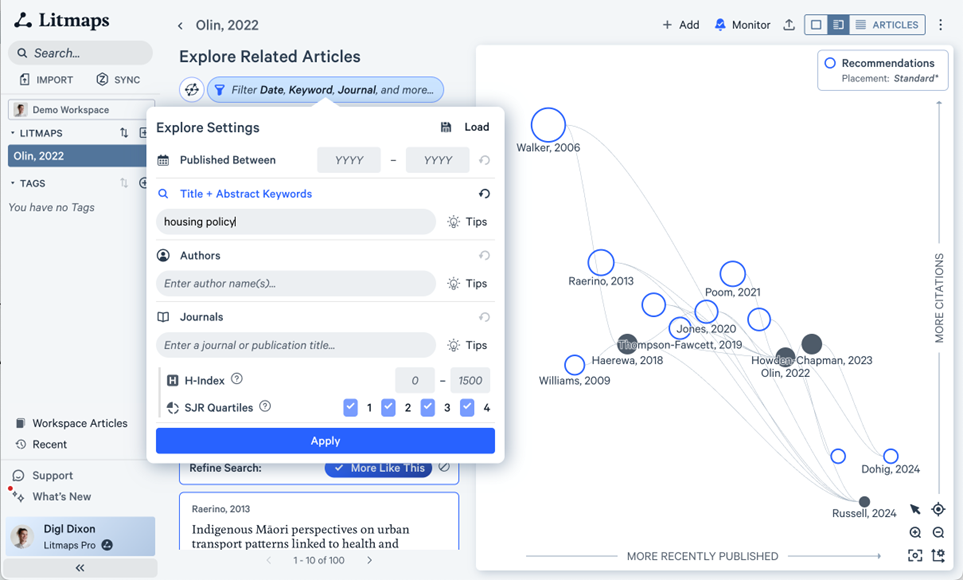

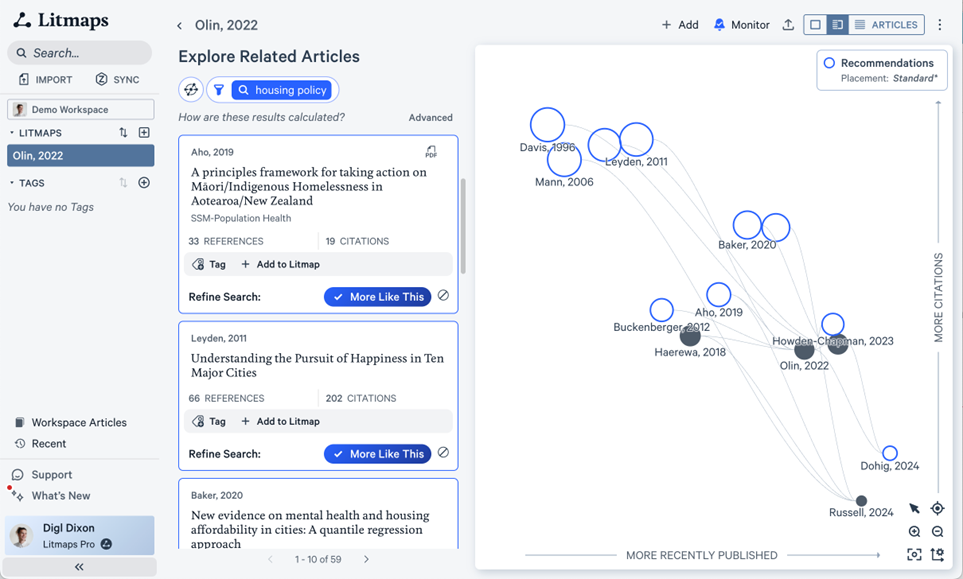

Continuing with our Citation Chasing, we may notice that many of these results, while about Aotearoa, are not about housing policy. We can force Litmaps to search for housing policy articles by adding a keyword filter. Now when Litmaps searches the citations and references of our article, it will exclude potential results that don’t include these keywords.:

Tip: You can see the other filters available to help refine your results. In particular, you might find the date range filter to be useful to limit your results to only those published recently.

Great! Now our results seem to be more focused on housing. After browsing these results, try adding keyword filters for your other topics, for example, “social cohesion”.

You can continue to grow your Litmaps by using the “More Like This” button to add articles to your Litmap.

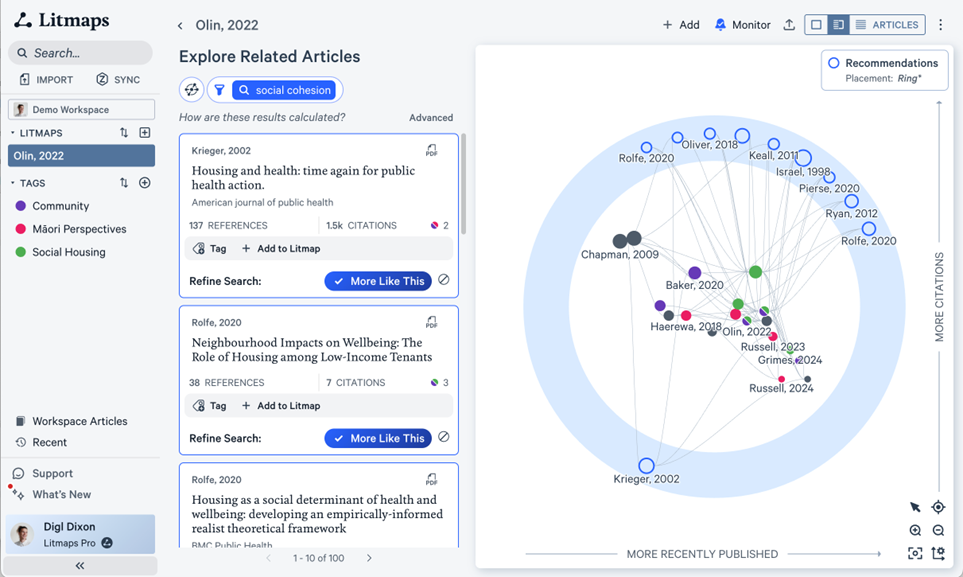

Here we can see our Litmap has continued to grow. We’ve even used Litmaps’ “tagging” feature to colour the nodes based on subtopics that are starting to emerge. These coloured tags make it easy to see how prospective results are connected with your findings. You can even use tags to generate whole new Litmaps, which will help focus your Citation Chasing results towards specific topics.

Software limitations

As with keyword searching databases, you should be aware that citation chasing software will only index a subset of the published literature. Additionally, the citation information associated with texts may have inaccuracies, such as missing or incorrect parts of a citation. These inaccuracies are often topic-specific, so make sure to check your findings against other databases: any large discrepancies in citation lists will reduce the software’s reliability.

Software in systematic research

Citation chasing software is an emerging technology and may not be accepted as a formal research process at your institution. For example, this means that you may not be allowed to include citation chasing software as part of your systematic literature review.

However, in this case you could still use citation chasing software to reverse-engineer your systematic review methods. If you find a text through citation chasing that wasn’t found from your systematic keyword search terms, you should update your keywords to ensure the new text is captured. You may even find more relevant work as you update your keywords this way!

In disciplines such as Health, a protocol may be used which will govern this. The Prisma 2020 protocol is often used in Health and while it doesn’t forbid the use of citation searching and citation-chasing software as the primary search method, it emphasises that these methods should be used as supplementary to traditional database searches to ensure a comprehensive and unbiased (Rethlefsen et al., 2021).

So what can I use aN AI tool for?

- Brainstorming ideas

- Checking or challenging your work

- Things you have mastered and don’t need to improve

The University of New South Wales has the very useful resource Tips for Using AI which answers the question: Are there any legitimate or ethical uses of AI in study and if so what are they and how?

Keeeping up with AI tOols for searching

I recommend subscribing to these sources:

Plan your search

Create your search strategy

Review Quiz

Further reading

QUT Library. (2024, December 1). Keeping useful notes. AIRS: Advanced Information Research Skills. https://airs.library.qut.edu.au/topics/7/4/

QUT Library. (2024, December 1). Coding the literature. AIRS: Advanced Information Research Skills. https://airs.library.qut.edu.au/topics/7/3/

Digital Essentials—Library—University of Queensland. (2024, October 18). https://web.library.uq.edu.au/research-tools-techniques/digital-essentials

References in this chapter

Bennett, B. (2022). How to write a policy brief. In J. L. MacArthur & M. Bargh, Environmental politics and policy in Aotearoa New Zealand (pp. 116–118). Auckland University Press.

Rethlefsen, M. L., Kirtley, S., Waffenschmidt, S., Ayala, A. P., Moher, D., Page, M. J., & Koffel, J. B. (2021). PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01542-z

Tolich, M., & Davidson, C. (2018). Social science research in New Zealand: An introduction. Auckland University Press.

![]()

- Bennett, M., Randal, J., & Wolf, A. (2025, August 1). Dispelling the illusion of learning: Shifting the culture for professional students in an AI future [Conference presentation]. AI & Society, Wellington, New Zealand. https://ecs.wgtn.ac.nz/Groups/AI_and_Society/AI_and_Society_Seminars#T2 ↵

- Bennett, M., Randal, J., & Wolf, A. (2025, August 1). Dispelling the illusion of learning: Shifting the culture for professional students in an AI future [Conference presentation]. AI & Society, Wellington, New Zealand. https://ecs.wgtn.ac.nz/Groups/AI_and_Society/AI_and_Society_Seminars#T2 ↵

The term "information landscape" refers to the diverse range of information sources and resources a researcher encounters and must navigate in the course of their research projects. Each discipline or field may be characterised by its established journals, publishers, and methods of scholarly communication. An information landscape includes both digital and print sources, including books, academic journals, official news organisations, informed commentary (blogs, opinion pieces, social media).

Words used to combine or exclude keywords in a search to improve results. AND, OR and NOT are the main operators.

When searching, recall refers to the number of results found. A broad or simple search finds or recalls a large number of results. A narrow or precise search finds a small number.

When searching, precision refers to the number of results found. A precise search search finds a small number of results.

Feedback/Errata