Introduction

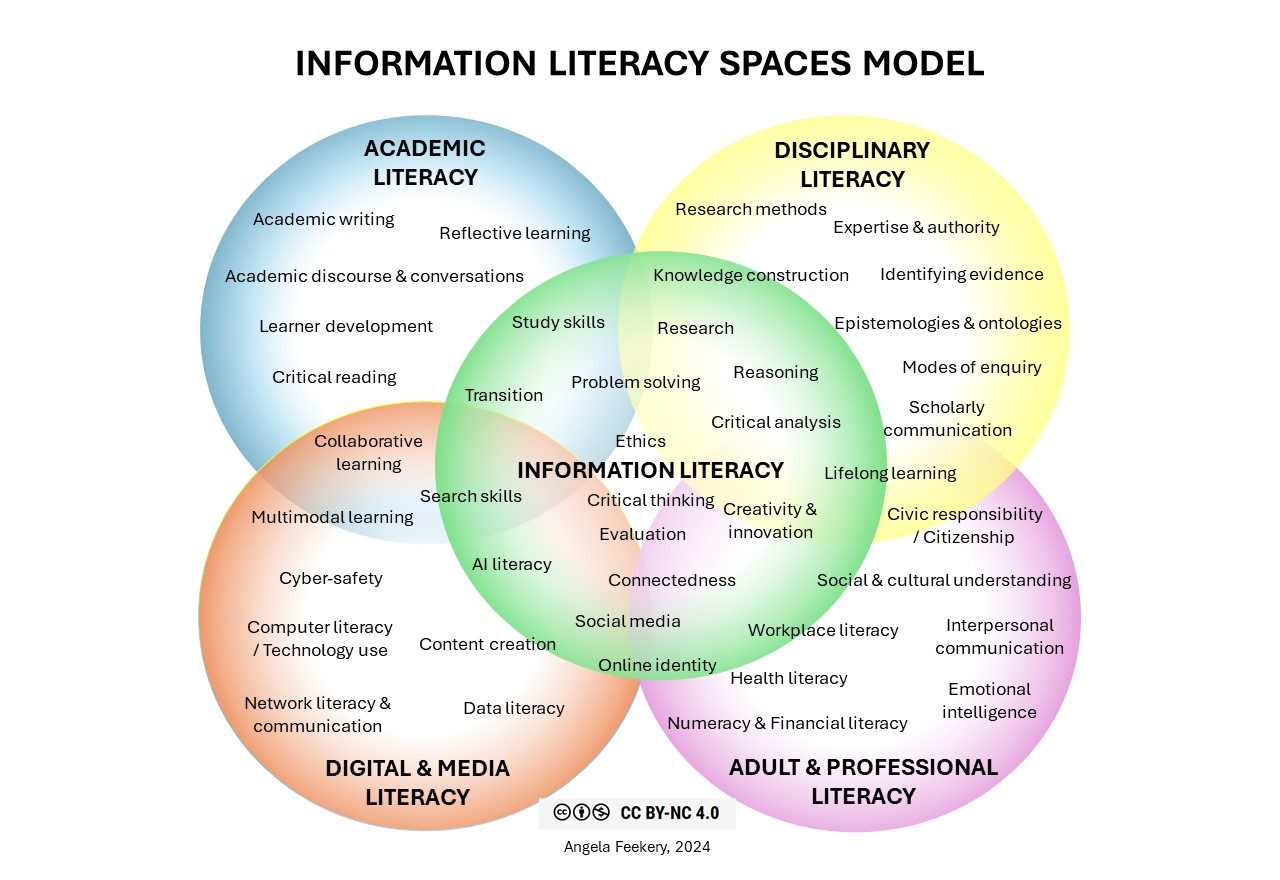

The Information Literacy Spaces Model will be the overarching model for this book. It places Information Literacy at the centre of your postgraduate academic learning and literacy spaces. The model will help you understand what information literacy means and how it is central to postgraduate academic study and research; it contextualises the skills you need and shows how they overlap and interrelate. It was updated in 2024 to include AI literacy.

The model is complementary and mutually inclusive to many other models, such as the Te Whatu Aho Rau information evaluation framework, which is presented in Chapter 4, Evaluating your information sources. It is at the current edge of the Information Literacy research literature.

Working effectively with information is key to successful postgraduate research. The effective and ethical use of information, especially scholarly information, will form the basis for writing essays, assignments, reports and examinations and constructing visual and oral presentations. Learning how to find information that matters and understand why it matters is important. Information and information literacy will provide links between your life experiences as a research student, the wider academic world of scholarship, and the post-academic, real-world, and professional applications of learning.

As an information-literate person, you will be able to:

- Understand your information needs (When do I need information? What type(s) of information do I need?)

- Determine where information is stored (Where is the best place to find this? Where should I search for the information?)

- Develop the skills to find and access the information (What tools are available to help me find the information? How do I use these tools?)

- Evaluate information to identify the “right” kind of information and discard the irrelevant information (Why is this information relevant and useful? Why do I trust this source of information?)

- Use and communicate effectively the information as in the form your lecturer requires (written, oral, visual) (How will I use the information?)

- Record and manage information effectively (How will I keep track of my information sources?)

Your university may describe the attributes students should have when they graduate.

Graduate profile

Victoria University of Wellington scholars

Victoria University of Wellington prepares its graduates to be scholars who:

- have a specialised understanding of their chosen field(s) of study

- exhibit well-developed skills in critical and creative thinking

- communicate complex ideas effectively and accurately in a range of contexts

- demonstrate intellectual autonomy through independence of thought, openness to ideas and information and a capacity to manage their own learning

- demonstrate intellectual integrity and understand the ethics of scholarship.

These attributes will be reflected in the formal curriculum and tested through academic assessment.

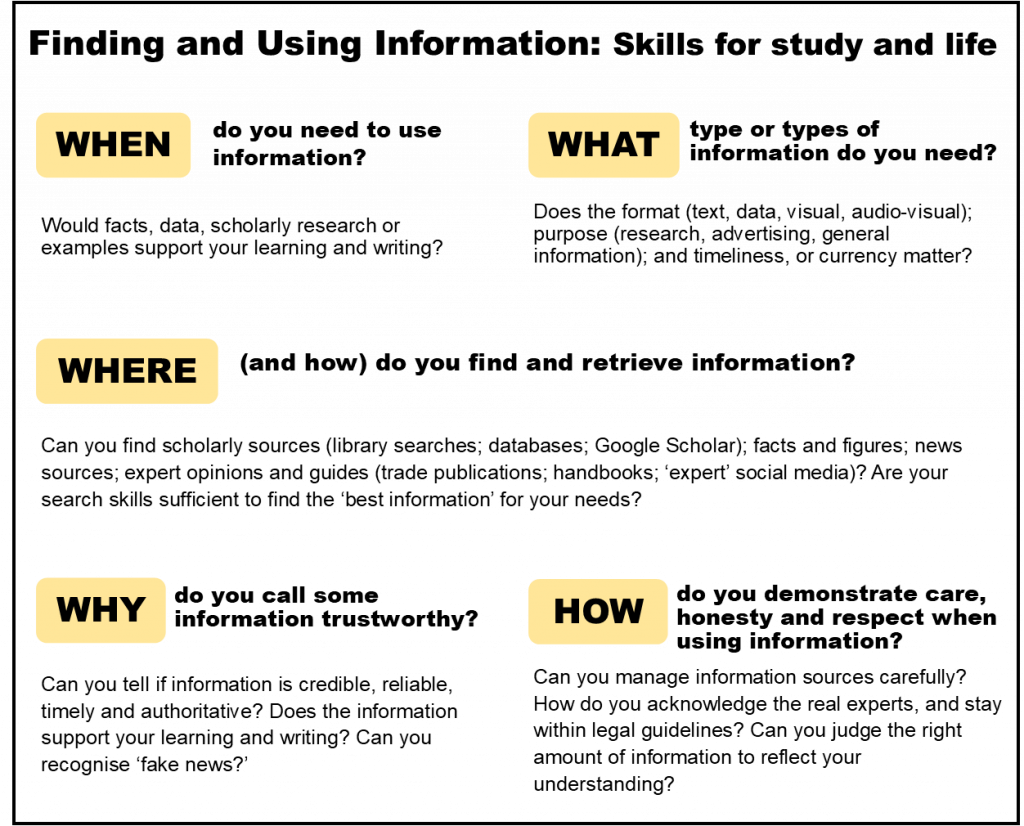

The figure below outlines the importance of information and information skills for study and for life:

Information literacy is the cornerstone of academic success, and for postgraduate students it is a transformative tool that empowers self-directed learning. The principle You are your own best teacher is particularly relevant as you navigate complex research environments and synthesise advanced knowledge. Postgraduate study often demands the ability to independently identify gaps in knowledge, critically evaluate sources, and integrate findings into new contexts. Research suggests that when learners actively engage with their educational journey, with reflective and independent practices, they enhance their competence and confidence in problem-solving. Claire Nader’s work reinforces this by emphasising responsibility in personal learning as a means of empowerment. For postgraduate students, this means mastering academic content and cultivating adaptability, intellectual curiosity, and critical inquiry (Nader, 2022). As you pursue your studies, embrace the mindset of an independent learner—view challenges as opportunities to grow and build resilience. Ultimately, the best learning comes from the questions you ask and the persistence you bring to uncovering answers. Be your own best teacher and bring your critical thinking skills to bear on your research, and you will do well. As you read this book, I hope you will benefit from each of the chapters and their authors’ input into each aspect of your postgraduate independent research journey with support from your Library.

Philip Worthington, Editor.

Artificial Intelligence

Advice and guidance on the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools for research is in the relevant chapters of the book. Bear these overall thoughts on AI in mind as you use this book:

Rather than reaching definitive conclusions about how AI will transform work, I find myself collecting observations about a moving target. What seems consistent is that, for now, the greatest value comes not from surrendering control entirely to AI or clinging to entirely human workflows, but from finding the right points of collaboration for each specific task—a skill we’re all still learning.

Mollick, E. (2025, January 26). Speaking things into existence. https://www.oneusefulthing.org/p/speaking-things-into-existence

Why Large Language Models Hallucinate

While large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT can generate authoritative-sounding prose on many topics and domains, they are also prone to just “make stuff up”. Literally plausible sounding nonsense! In this video, Martin Keen of IBM explains the different types of “LLMs hallucinations”, why they happen, and ends with recommending steps that you, as a LLM user, can take to minimize their occurrence.

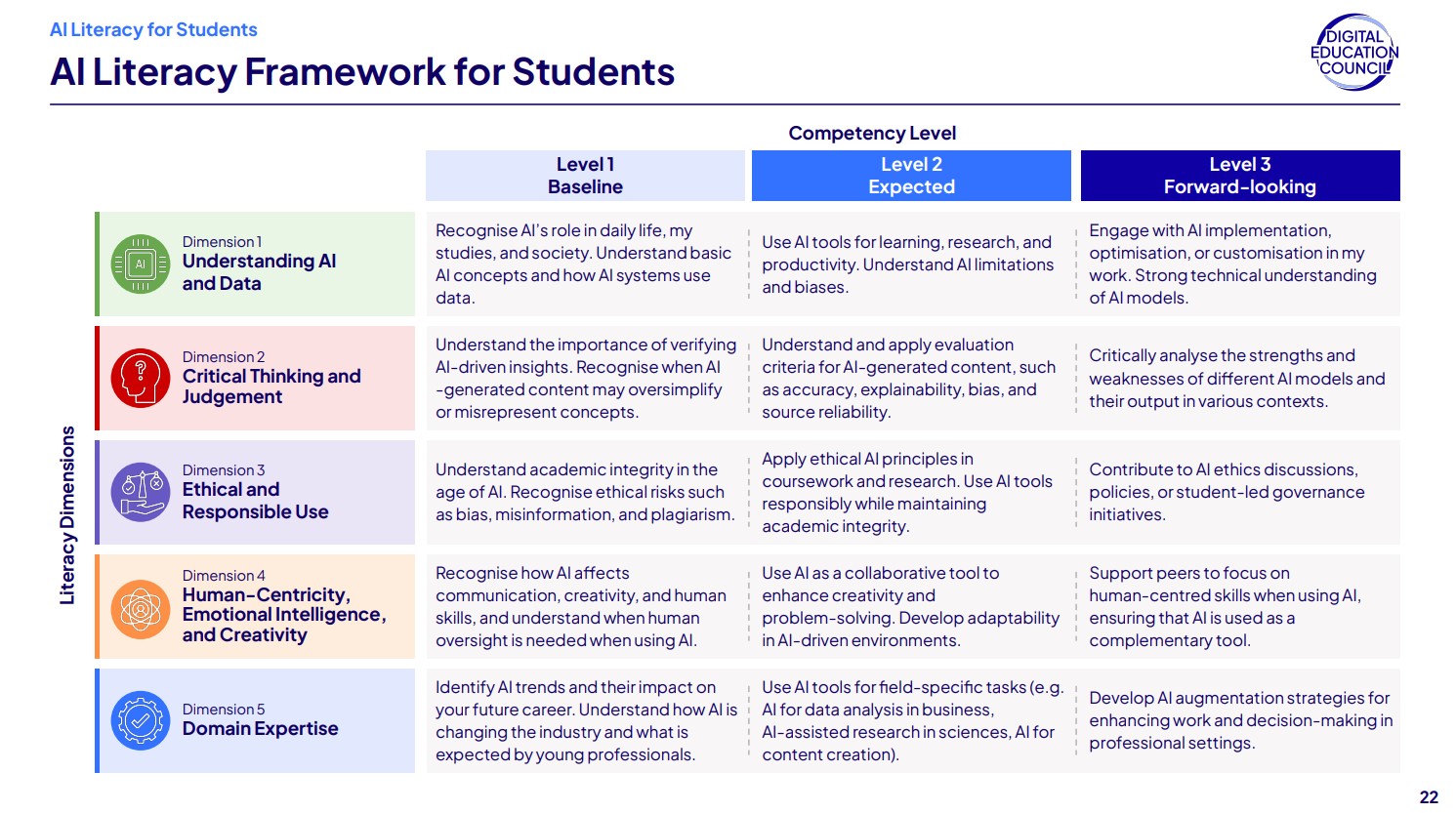

AI Literacy for Students

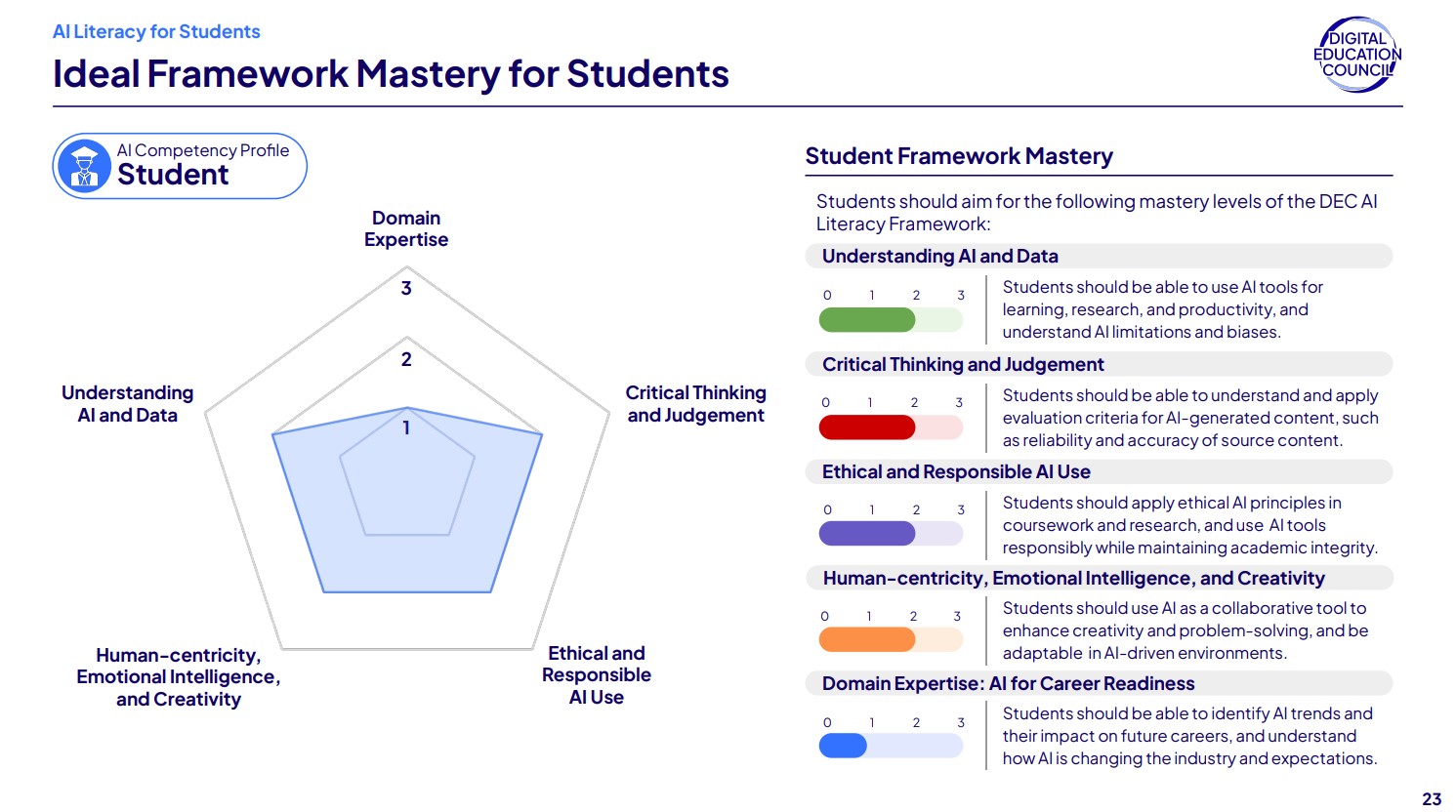

The Digital Education Council (Australia) has created an AI framework for students and suggests aiming for the mastery levels below.

Source: Digital Education Council, DEC AI Literacy Framework , 2025.

Long description #1 – Information Literacy Spaces Model

The Information Literacy Spaces Model presents four overlapping domains that represent the diverse literacies postgraduate researchers need to navigate academic and professional environments.

Academic Literacy focuses on foundational scholarly skills. These include academic writing, reflective learning, engaging in academic discourse and conversations, learner development, and critical reading.

Disciplinary Literacy emphasises domain-specific expertise. It includes research methods, understanding expertise and authority, constructing knowledge, identifying evidence, exploring epistemologies and ontologies, modes of enquiry, and scholarly communication.

Digital & Media Literacy encompasses competencies in multimodal learning, cyber-safety, technology use, networked communication, search strategies, AI literacy, content creation, and data literacy.

Adult & Professional Literacy covers broader life and career skills. These include lifelong learning, civic responsibility and citizenship, social and cultural understanding, interpersonal communication, emotional intelligence, numeracy, financial literacy, health literacy, and workplace literacy.

At the intersection of these four domains lies Information Literacy. This central space integrates and connects the skills from each area. It includes critical thinking, evaluation, creativity, innovation, connectedness, social media use, online identity management, ethics, problem solving, transition skills, study strategies, research reasoning, critical analysis, and knowledge construction.

The overlapping structure of the model highlights how these literacies are not isolated but interdependent. For example, effective academic writing may require understanding disciplinary conventions, using digital tools, and communicating professionally. Information Literacy serves as the integrative core, enabling researchers to apply these skills fluidly across contexts.

Long description #2 – Finding and Using Information: Skills for study and life

WHEN do you need to use information?

Would facts, data, scholarly research or examples support your learning and writing?

WHAT type or types of information do you need?

Does the format (text, data, visual, audio-visual); purpose (research, advertising, general information); and timeliness, or currency matter?

WHERE (and how) do you find and retrieve information?

Can you find scholarly sources (library searches; databases; Google Scholar); facts and figures; news sources; expert opinions and guides (trade publications; handbooks; ‘expert’ social media)? Are your search skills sufficient to find the ‘best information’ for your needs?

WHY do you call some information trustworthy?

Can you tell if information is credible, reliable, timely and authoritative? Does the information support your learning and writing? Can you recognise ‘fake news’?

HOW do you demonstrate care, honesty and respect when using information?

Can you manage information sources carefully? How do you acknowledge the real experts, and stay within legal guidelines? Can you judge the right amount of information to reflect your understanding?

![]()

Feedback/Errata