6.1 A Simple Model

What is a Model?

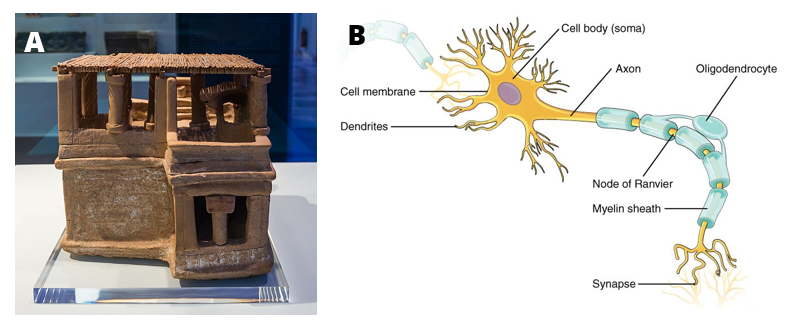

In the physical world, “models” are generally simplifications of things in the real world that nonetheless convey the essence of the thing being modelled. For instance, a model of a building conveys the structure of the building while being small and light enough to pick up with one’s hands (Figure 6.1.1-A). A model of a neuron that you see in textbooks is usually much larger than the actual thing, but it conveys the major parts of the cell and their relationships (Figure 6.1.1-B).

In statistics, a model is meant to provide a similarly condensed description, but for data rather than a physical structure. Like physical models, a statistical model is generally much simpler than the data being described; it is meant to capture the “essence” of the data as simply as possible. In both cases, we realise that the model is a convenient fiction that necessarily glosses over some of the details of the actual thing being modelled. As the statistician George Box famously said: “All models are wrong but some are useful.”[1]

It can also be useful to think of a statistical model as a theory of how the observed data was generated; our goal then becomes to find the model that most efficiently and accurately summarises this data generation process. But as we will see later on, the desires for efficiency and accuracy will often be diametrically opposed to one another.

Let’s start with a simple model explained using an analogy.

Last weekend, I went to Bunnings[2] as I wanted to get a portable key holder for when I go diving with my partner.

While in the store, I was presented with different products to choose from. I had two main criteria–1) our car keys needed to fit inside the key holder, and 2) it must be less than $50. The second criterion was easy to achieve, I just need to look at all the products that are less than $50. The first criterion (and arguably, the most important criterion) is a bit trickier to achieve because unfortunately, I left my car keys with my partner.

So I have a problem, I needed to estimate the dimensions of my car keys. Granted, I could have gone back to the car, got the keys and measured it against the locks. But alas, laziness took over.

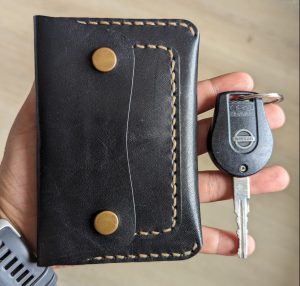

One way of solving my problem is to model the dimensions of my car keys using the length of another object that is similar to it. I had my wallet, and sometimes, I put my keys into my wallet–so I got a measuring tape (I am in a hardware store after all) to measure the length of my wallet.

The first thing you would have noticed was that, from the outset, my model is not great. In fact, it’s a terrible model. Although my model has a length, there are a lot of details that were not captured. For instance, I don’t know the width and depth of the remote attached to the keys. Plus as you can see in Figure 6.1.3 above, my wallet is much longer than my keys.

If we were to write an equation in words to represent this model, it might look something like this:

![]()

The “error” bit in the equation represents the deviations from the model. We want to minimise errors as much as possible. But as you can see from above, there were a lot of errors in my model. Using the length of my wallet as a model for my keys is a gross oversimplification of the different necessary attributes of the real thing. According to CourseKata (2020), models are always like this: they oversimplify some aspects of the world, and focus only on the dimension you are most interested in.[3]

In the end, the portable key lock I bought was too big (and too expensive) and had to return to the store the next day to exchange it for a more suitable one. This time, I measured the dimensions of my keys before going back to the store.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/All_models_are_wrong ↵

- For non-Australian readers, Bunnings is an Australian household hardware and garden centre chain. It is akin to Home Depot. ↵

- CourseKata (2020), Chapter 5: A simple model. In Statistics and data science: A modelling approach. https://coursekata.org/preview/book/e7ab06dd-53fd-4397-930b-72f21bcb1efb/lesson/8/0 ↵