3.7 Research Design II: Non-Experimental Designs

Researchers who are simply interested in describing characteristics of people, describing relationships between variables, and using those relationships to make predictions can use a non-experimental research design. Using the non-experimental approach, the researcher simply measures variables as they naturally occur, but they do not manipulate them.

For instance, if a researcher is interested in measuring the number of traffic fatalities in Queensland last year that involved mobile phones, a researcher may not be able to manipulate ‘mobile phone use while driving’, but can simply collect data about a phenomenon that has already occurred. Another example would be standing at a busy intersection and recording the driver’s gender and whether or not they were using a mobile phone while they pass through the intersection, and then analysing the data to see whether men or women are more likely to use a mobile phone when driving. Again, this time, the researcher is just observing the variables (use of mobile phone and gender) and is not manipulating anything.

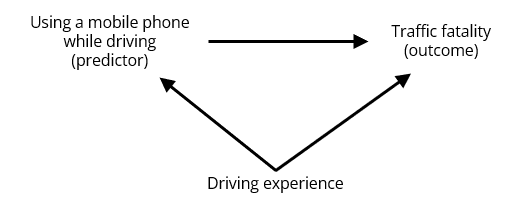

It is important to point out that ‘non-experimental’ does not mean nonscientific. Non-experimental research is still scientific in nature. It can be used to fulfil two of the three goals of science (to describe and to predict). However, unlike experimental research, we cannot make causal conclusions using this method as the researcher does not have full control of all aspects of the design. With the example we used above, it is possible that there is another variable that is not part of the research hypothesis but that causes both the predictor and the outcome variable and thus produces the observed correlation between them.

There are different examples of non-experimental designs and we will cover some of these types below.

Case Studies

Case studies involve the idiographic, observational (and/or interview) study of an individual or individuals by the researcher, such as within a clinical context where the focus might be on the participant’s lived experience. A famous example of a case study in psychology is the case of Phineas Gage. In 1848, Gage, a railroad worker, survived a severe brain injury when a metal rod was accidentally driven through his skull, damaging his frontal lobes. Remarkably, Gage survived the injury and was able to walk and talk normally, but his personality and behaviour underwent dramatic changes.

Case studies allow for a detailed and in-depth examination of the individual, group, or situation under investigation. Researchers can gather a wealth of information about the person or phenomenon being studied. Unique or rare cases (like Phineas Gage) are particularly useful for studying unique or rare cases that may not be easily observed or studied in other ways. Case studies can be used to generate hypotheses or ideas about potential cause-and-effect relationships that can be tested in future research.

However, as with any research designs, case studies are limited due to the following reasons:

- Limited generalisability: Due to the focus on a single individual, group, or situation, case studies have limited generalisability to larger populations. It may be difficult to generalise findings from a case study to the wider population.

- Subjectivity: Case studies are often subjective, as researchers may have personal biases or interpretations that influence their analysis and conclusions.

- Lack of control: Case studies lack experimental control, which makes it difficult to establish cause-and-effect relationships. It is also difficult to replicate the same conditions across different cases, making it difficult to determine if the findings are consistent.

Quasi-Experimental Designs

A quasi-experimental design is essentially a hybrid of experimental and non-experimental designs. It aims to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between an independent and dependent variable. However, unlike a true experimental design, a quasi-experiment does not rely on random assignment. Instead, subjects are assigned to groups based on non-random criteria.

Quasi-experimental designs are common in psychology research and feature non-random assignment to condition and/or non-manipulation of independent variables, often through necessity. As an example, imagine that some school authorities in Queensland want to implement a new math curriculum and they are interested in determining whether the curriculum is effective in improving student performance. The school authorities decide to implement the new curriculum in one school but not in another. They then compare the test scores of the students in both schools before and after the implementation of the new curriculum.

Since the assignment of the schools to the different conditions (new versus old curriculum) was not random, this is a quasi-experimental design. The study attempts to establish a causal relationship between the new curriculum and student performance by comparing the pre-post scores of the two groups. However, there may be other factors that could account for the differences observed between the two groups, such as differences in student populations or teacher quality. Therefore, the study has limited internal validity.