3.2 Introduction to Psychological Measurement

Research starts with identifying what you want to learn, and then determining how you plan to study it. Therefore, we will start our brief introduction to research methods with variables and psychological measurement.

What do we Mean by Psychological Measurement?

Measurement is the assignment of scores to individuals so that the scores represent some characteristic of the individuals. This very general definition is consistent with the kinds of measurement that everyone is familiar with — for example, weighing oneself by stepping onto a bathroom scale or checking the internal temperature of a roasting turkey using a meat thermometer.

This general definition of measurement is consistent with measurement in psychology too. You may imagine a clinical psychologist who is interested in how depressed a person is. He administers the Beck Depression Inventory, which is a 21-item self-report questionnaire in which the person rates the extent to which they have felt sad, lost energy, and experienced other symptoms of depression over the past two weeks. The sum of these 21 ratings is the score and represents the person’s current level of depression.

Variables that we Study in Psychological Research

Many variables studied by psychologists are straightforward and simple to measure. These include age, height, weight and birth order. You can ask people how old they are and be reasonably sure that they know and will tell you. Other variables studied by psychologists — perhaps the majority — are not so straightforward or simple to measure. We cannot accurately assess people’s level of intelligence by looking at them, and we certainly cannot put their self-esteem on a bathroom scale to measure it. We sometimes call these variables “constructs”.

Psychological constructs are difficult to observe directly. One reason is that they often represent tendencies to think, feel or act in certain ways. Often, these constructs often involve internal processes. For example, to say that a particular university student is highly extroverted does not necessarily mean that she is behaving in an extroverted way right now. In fact, she might be sitting quietly by herself, reading a book. Instead, it means that she has a general tendency to behave in extraverted ways (e.g., being outgoing, enjoying social interactions etc.) across a variety of situations.

How do we Measure These Psychological Constructs?

Even though psychological constructs are difficult to measure, we still try anyway. We call this process operationalisation. We define and explain variables in terms of how they will be measured. In other words, “operationalisation is the process by which we take a meaningful but somewhat vague concept and turn it into a precise measurement” (Navarro and Foxtrot, 2022).[1] Navarro and Foxtrot (2022) also provide the process of operationalisation, which involves:

- Being precise about what you are trying to measure. For instance, does “age” mean “time since birth” or “time since conception” in the context of your research?

- Determining what method you will use to measure your variables. Will you use self-report to measure age, ask a parent, or look up an official record? If you’re using self-report, how will you phrase the question?

- Defining the set of allowable values that the measurement can take. Note that these values don’t always have to be numerical, though they often are. When measuring age the values are numerical, but we still need to think carefully about what numbers are allowed. Do we want age in years, years and months, days or hours? For other types of measurements (e.g., gender) the values aren’t numerical. But, just as before, we need to think about what values are allowed. If we’re asking people to self-report their gender, what options do we allow them to choose between? Is it enough to allow only “male” or “female”? Do you need an “other” option? Or should we not give people specific options and instead let them answer in their own words? And if you open up the set of possible values to include all verbal response, how will you interpret their answers?

Let’s focus on the second point, determining what method you will use to measure your variables. Methods of measurement generally fall into one of three broad categories. Self-report measures are those in which participants report their own thoughts, feelings, and actions, such as the Beck Depression Inventory. Behavioural measures are those in which some other aspect of participants’ behaviour is observed and recorded. This is an extremely broad category that includes the observation of people’s behaviour both in highly structured laboratory tasks and in more natural settings. Finally, physiological measures are those that involve recording any of a wide variety of physiological processes, including heart rate and blood pressure, galvanic skin response, hormone levels, and electrical activity and blood flow in the brain.

Levels of Measurement

Now, let’s further discuss the third point. The psychologist S. S. Stevens suggested that scores can be assigned to individuals in a way that communicates more or less quantitative information about the variable of interest (Stevens, 1946).[2] For example, the officials at a 100 metre race could simply rank order the runners as they crossed the finish line (first, second, etc.), or they could time each runner to the nearest tenth of a second using a stopwatch (11.5 sec, 12.1 sec, etc.). In either case, they would be measuring the runners’ times by systematically assigning scores to represent those times. Stevens provided a framework for categorising variables based on their level of measurement or amount of information that they provide, which is called scales of measurement (also known as levels of measurement). The four levels are nominal, ordinal, interval and ratio, which we will discuss further below.

Nominal Variable

Nominal level of measurement is one in which variables are classified based on their names or categories. They do not have any order, ranking or mathematical significance. For example, gender (male, female), hair colour (black, brown, blonde), and country of origin are all examples of nominal level variables.

Ordinal Variable

Ordinal level of measurement involves variables that have an inherent order or ranking, but the difference between values is not necessarily equal. For example, social class (lower, middle, upper), education level (primary, high school, university) and levels of satisfaction (unsatisfied, neutral, satisfied) are all examples of ordinal variables. They can be arranged in a sequence, but the difference between the values is not meaningful in mathematical terms.

Unlike nominal scales, ordinal scales allow comparisons of the degree to which two individuals rate a particular variable. For example, we know that unsatisfied would be a lower rating of satisfaction compared to neutral.

Interval Variable

An interval scale has all of the features of an ordinal scale, but in addition, the intervals between units are meaningful. A standard example is physical temperature measured in Celsius or Fahrenheit; the physical difference between 10 and 20 degrees is the same as the physical difference between 90 and 100 degrees, but each scale can also take on negative values.

Interval variables do not have a true zero point. The Celsius scale illustrates this issue. Zero degrees Celsius does not represent the complete absence of temperature (the absence of any molecular kinetic energy). In psychology, the intelligence quotient (IQ) is often considered to be measured at the interval level. While it is technically possible to receive a score of 0 on an IQ test, such a score would not indicate the complete absence of IQ.

Ratio Variable

Finally, the ratio level of measurement assigns scores with a true zero point that represents the complete absence of the quantity being measured. Examples include height measured in metres and weight measured in kilograms. This level also applies to counts of discrete objects or events, such as the number of siblings one has or the number of questions answered correctly on an exam.

Why is this important?

Why does it matter whether a variable is nominal, ordinal, interval or ratio?

The most important takeaway from this is that some calculations would not make sense on some types of data. For example, imagine that we were to collect postal code data from 200 people in living in Brisbane, Australia. Even though postal codes may look like an interval variable, they don’t actually refer to a numeric scale. Each postcode basically serves as a label for a different region. For this reason, it wouldn’t make sense to talk about the average postal code, for example.

Furthermore, statistical software like jamovi assumes that the variables we are trying to analyse will have a specific measure. For instance, it would not make sense to compute an average of people’s hair colour (given that this is a nominal variable). For the most part however, researchers just mostly care about distinguishing between nominal variables and all the others.

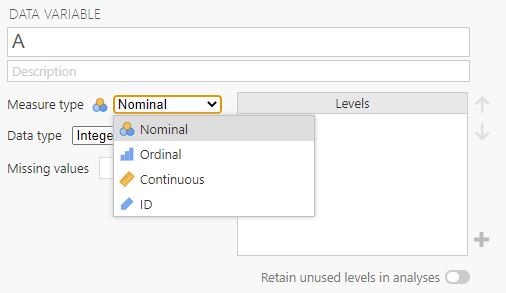

As shown in the previous chapter, there are only three measures that you can choose for your variables in jamovi: continuous (which can be used for ratio and interval variables), ordinal and nominal. See the image below for the options available in jamovi.

Discrete Versus Continuous Measurements

There’s a second kind of distinction that you need to be aware of regarding what types of variables you can run into. The difference between these is as follows:

- A discrete measurement is one that takes one of a set of particular values. These could be qualitative values (for example, different breeds of dogs) or numerical values (for example, how many friends one has on Facebook). Importantly, there is no middle ground between the measurements; it doesn’t make sense to say that one has 33.7 friends.

- A continuous measurement is one that is defined in terms of a real number. It could fall anywhere in a particular range of values — for instance, response time is continuous. If Bella takes 3.1 seconds and Isaac takes 2.3 seconds to respond to a question, then Gabby’s response time will lie in between if he took 3.0 seconds to respond.

Chapter attribution

This chapter contains taken and adapted material from several sources:

- Statistical thinking for the 21st Century by Russell A. Poldrack, used under a CC BY-NC 4.0 licence.

- Research methods in psychology by Rajiv S. Jhangiani, I-Chant A. Chiang, Carrie Cuttler and Dana C. Leighton, used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence.

- Screenshots from the jamovi program. The jamovi project (V 2.2.5) is used under the AGPL3 licence.

- Navarro, D. J., & Foxcroft, D. R. (2022). Learning statistics with jamovi: A tutorial for psychology students and other beginners (Version 0.75). https://doi.org/10.24384/hgc3-7p15 ↵

- Stevens, S. S. (1946). On the theory of scales of measurement. Science, 103, 677–680. ↵