75 Updating models of change

In 2005, I wrote a short paper titled Possible futures for physiotherapy with my colleague, Peter Larmer [1]. In the paper, we suggested that there were broadly four directions of travel available to future physiotherapists: to do nothing, to return the profession to its roots, to develop an entirely new professional identity, or to find a way to combine the best of the old with the best of the new. We suggested there were good and bad aspects to each of these approaches, even doing nothing. But in a follow-up paper in 2009 [2], we argued that, in reality, the fourth option was the only real choice. Now I am not so sure.

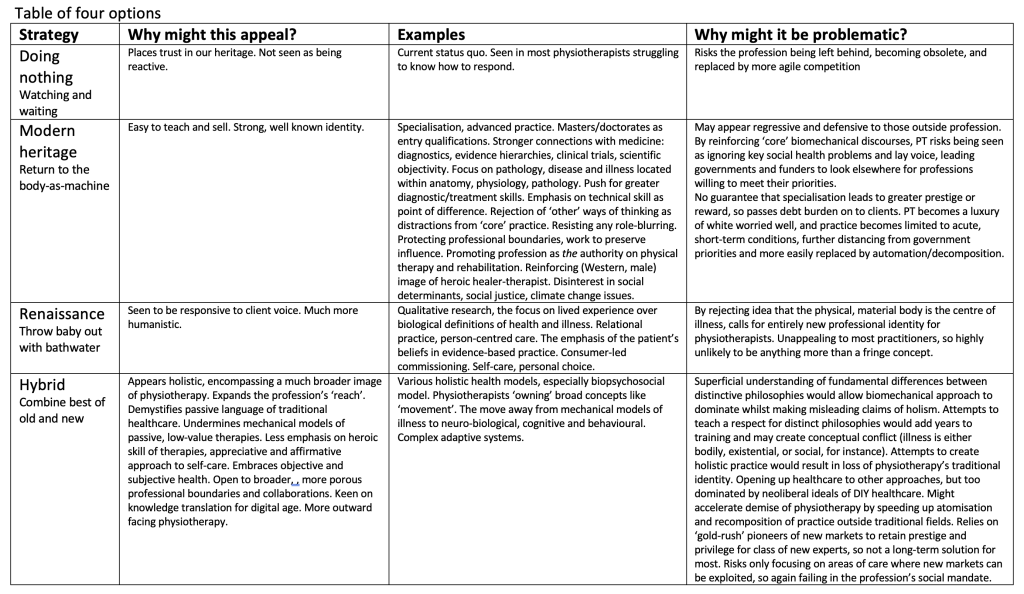

The four approaches represented broad archetypes of the ways physiotherapists are adapting to the changing face of healthcare. And although they appeared to take the profession in radically different directions — either by attempting to restore it to former glory, fundamentally reshape it, or find some middle path — they all shared a common desire to promote the physiotherapy profession and see it prosper. The four approaches are summarised in the table below. After that, I consider each in turn in more detail.

Table of four options – pdf version

Doing nothing

Being ‘late adopters’, watching and waiting, being cautious, or simply hoping that when change comes it isn’t too disruptive, seems like a dangerous approach to take, given what is now happening in healthcare. It seems inconceivable that physiotherapy can rely on the fact that it has enough social credit in the bank to wait out the maelstrom that is 21st century healthcare and come out on the other side intact. So, we should probably dispense with the first of our four approaches straight away. And yet, a significant number — perhaps even the majority — of physiotherapists are either choosing to take this approach, or feel they have little capacity to do otherwise. Some of this may stem from their lack of structural power, but some also derives from not knowing how to engage in socio-political reform [3][4]. For many it is the busyness of daily practice, or a misplaced confidence in the security of the profession that engenders inertia. Whatever the reason, many physiotherapists are choosing to concentrate on their clinical practice, teaching, and clinical research, rather than on structural reform. And so doing nothing has to be considered as one of the ways physiotherapists are shaping the profession in the future.

Modern heritage

The second approach is much more purposeful and directive, and concerns efforts to restore some of the profession’s prestige and confidence by reviving what are seen as the profession’s core principles (see Table above for examples). I refer to this approach here as modern heritage. The hope of a modern revival of the profession’s heritage is that a return to the values that established physiotherapy as a profession will still have currency today, and can still be traded in for greater professional autonomy, social, and economic capital.

For a contemporary example of this logic at work, see the recent Australian Physiotherapy Association’s 2020 report on the value of physiotherapy in Australia. Note that the economic value of the physiotherapy profession is conflated with the benefits of particular treatment modalities. And that while benefits are expressed in highly specific dollar values (i.e. an average $6,626 net economic benefit of physiotherapy in the treatment of episodes of Parkinson’s disease), no such detail is provided about costs.

Modern heritage can be found in attempts to revive what some see as the historical core of the profession: a strong connection with biomedicine; a focus on illness and injury as a biological (as opposed to interpretive or social) phenomenon; depersonalised objectivity, scientific reason, and rational empiricism. But modern heritage is not merely an act of reminiscence. Rather, it emphasises the use of evidence-based practice, systematic clinical trials research, and the latest advances in bioscience to promote the idea of a rigorous, efficient, and effective 21st century profession.

There is much to commend this approach. In the first instance, it is a very familiar image of physiotherapy for most practitioners. The vast volumes of quantitative clinical research now being conducted mean that even those who felt insecure about their knowledge of systematic review methodology, would at least be comfortable with studies that took traditional physiotherapy subjects, such as common injury pathways, the reliability of diagnostic tests, and treatment efficacy, and analysed them in new ways. A modern heritage approach is also a relatively easy approach to market because it retains many of the hallmarks of physiotherapy known to the public, funders, and legislators. Educators have little difficulty adapting curricula, and the development of specialisms and advanced practice stay true to existing professional structures.

There are some significant risks attached to the modern heritage approach, though. Firstly, it relies on the latest research to show that the profession is rigorous, efficient, and effective. Clinical trials research to date has been ambivalent on this point, and many of the approaches used by physiotherapists in the past have been shown to have limited efficacy. There is a risk, then, that the pursuit of greater scientific rigour undermines the very essence of the profession that modern heritage approaches seek to promote. Politically, in a time when the professions’ claims to goodness and expertise are being unbundled (see Chapter 8), attempts to re-assert physiotherapy’s prestige may appear self-interested and retrograde.

While these tensions can appear somewhat abstract, they are having a direct impact on physiotherapy practice. One of the key ways modern heritage approaches assert themselves, for instance, is through specialisation. Over recent decades, we have seen real interest in the development of different forms of expert, advanced, and specialised practice. Critically, these conform to classical reductive medical specialties like musculoskeletal, neurological, and cardiorespiratory physiotherapy, and pathway programmes are looking to link specialisation to improved social, and economic, capital.

A second example comes from the astonishing debt crisis now affecting physiotherapy students in the United States. According to the American Physical Therapy Association, ‘PT graduates are in debt for an average of nearly $153,000 — an amount that doesn’t include mortgage debt. For nearly all of those PTs, most of their debt load is related to their PT education, with an average balance of $116,000 in related debt’ [5]. The average amount of educational debt alone owned by entry-level APTA member PTs in Florida was equal to almost two years of salary (197% debt-to-income ratio). More than a new grad doctor or vet [6]. The APTA recognises that the cost of physiotherapy education is a major barrier to the diversity of the profession, but puts the importance of demonstrating the special status of physical therapists above all of these concerns [7][8].

Specialisation is always an arms-race based on the capitalistic idea that competition for limited resources is the engine for unlimited growth. But there have to be limits at some point, and these may now be being reached in healthcare. As Cornell Professor of Management and Economics, Robert Frank, argued, specialisation is ultimately like going to a concert and standing to get a better view of the stage. Now, suddenly, the person behind you can’t see so stands up as well. Soon everyone is standing, no-one has a better view, but everyone is less comfortable.

If specialism means that ‘there can be few beneficiaries of the genuinely outstanding’ [9], or where ‘The expertise of a very few… [is only] bestowed upon a few’ (ibid), then it is unlikely that governments and other funders will be keen to support such a project. And so, as with the new student debt crisis, the costs of elitism will need to be borne by the consumers, creating ‘a Rolls-Royce service for the well-heeled minority, while everyone else is walking’ (ibid). Physiotherapists may be forced to focus on cheaper, measurable, short-term interventions for acute, self-limiting conditions to counterbalance the rising cost of their labour. This may be to the profession’s advantage in the short term, particularly if the goal is to raise the prestige of the profession with affluent clients in high-income countries, but it is the exact opposite of the kinds of flexible and holistic healthcare that many nation states are now calling for from their health professionals. Technological disruption would also make this kind of instrumental labour a prime target for future work decomposition and automation.

The deeper tragedy here is the failure of advocates for the modern heritage approach to realise that expertise does not occupy the same social space today as it did in the golden age of medicine. This is one of the unfortunate consequences of the physiotherapy paradox. By focusing on the body-as-machine, many physiotherapists have failed to recognise the real drivers of change in healthcare, and believe that more of the same, done better, will be the answer to the profession’s future prosperity. But consumers have many more options available to them these days, and governments are no longer eager to centralise services around a few ‘elite’ biomedical professions.

But if this were not enough, we should not forget that there are other, perhaps more pernicious, dangers hiding in the modern heritage approaches that need to be considered. Any way of seeing is also a way of ‘not seeing’ [10], and the profession’s heritage has allowed generations of physiotherapists to ignore the myriad other ways of understanding health and illness, in favour of seeing the body-as-machine. The danger is, then, that a modern heritage approach perpetuates the kinds of gendering of healthcare, normalisation of disability, and othering of colonialism, that have been some of the worst professogenic effects of biomedicine over its lifetime. For all of these reasons, I would argue the modern heritage approach is an unsuitable and, in some cases, unethical, route to take for the profession into the future.

Renaissance physiotherapy

One of the characteristic features of the modern heritage discourse is its turn back to the body-as-machine, and the rejection of interpretive and sociological aspects of healthcare. As its name suggests, renaissance physiotherapy is a radical departure from this approach, arguing that the future for physiotherapy lies in departing from the profession’s traditions, placing the focus, instead, on the client’s subjective lived experience, experiential philosophies, and the relational nature of contemporary practice.

Renaissance physiotherapy draws heavily on the social action theories of symbolic interactionism and phenomenology outlined in Chapter 6. Its primary concern is to shape therapy around the meanings people give to health and illness, either as people in themselves, or through their relationships with others. Illness resides not within the body, but in the person’s meaning-making, and healthcare is a relational process of meaning-making, rather than a biological construct. So, a therapist who believes that each client/patient’s experience of health and illness is unique, or that the subjective experience of illness is a more significant determinant of a person’s health than any underlying pathology, might favour renaissance physiotherapy.

As with modern heritage, there is also much that supports this approach, not least because, in the West at least, people’s individual opinions matter much more than they used to. Asking people for their opinions, their views on events, or their consumer preferences, is a relatively recent phenomenon dating back to the birth of modern advertising [11]. And this has been made even more significant by the advent of social media. Now, the most common complaints from healthcare service users are about poor communication and being heard. Renaissance physiotherapy puts the client’s voice at the centre of the relationship, critiquing the over-medicalisation of health, and rejecting the idea that pathology defines illness. In this sense, this approach shows those outside physiotherapy that the profession is willing to adapt to a healthcare environment that is much more person-centred and open to reform.

Advocates draw heavily on qualitative, hermeneutic, relational, and interpretive approaches to healthcare, pioneered in nursing, psychotherapy, and the medical humanities. To date, however, only a handful of studies have explored the possibility of this approach in physiotherapy. And of these, none have extrapolated the approach from day-to-day practice to the renaissance of the profession as a whole.

In part, this is because advocates for renaissance would struggle to account for the pivotal role the real, material body plays in physiotherapy. Not unreasonably, if the material body is dismissed altogether, physiotherapy would need to find an entirely new locus for its identity. It would lose its connection to its past and would, in all likelihood, need to make new connections with the public, governments, and funders, at a time when they may balk at more instability.

An interpretive approach also falls short in saying little about gender, class, poverty, race, ableism, homophobia, activism, stigma, and a host of other sources of social oppression. These are often absent from the qualitative literature in physiotherapy, which has tended to focus on people’s lived experience, but not the social conditions that shape the ways it is possible for people to think and act. This is a criticism that has been levelled at nursing in recent years [12], leading to ‘patient‐focused nursing practice being conceptualised, taught, and promoted as an apolitical process’ [13].

In reality, an interpretive, relational renaissance is highly unlikely in physiotherapy, but that does not mean it should be discounted. Healthcare is becoming increasingly person centred, self-care, consumer choice, and personal responsibility are all very much in vogue [14]. In reality, though, physiotherapy is so inexorably tied to the material body that any approach that incorporated more interpretive and relational approaches would need to do so as a hybridised version of contemporary practice.

Hybrid physiotherapy

Where modern heritage discourses appear regressive and overly defensive, and renaissance approaches too much of a departure from the profession’s past, hybrid physiotherapy feels, to some, the ideal solution because it blends the best of the old with the best of the new. There are three major claims made by the constellation of existing approaches to physiotherapy that we might call ‘hybrid’ that physiotherapy can be:

- Holistic, marrying psycho-social approaches to the biomedical and moving the profession beyond its traditional focus on the body-as-machine;

- Person-centred;

- Responsive to the changing healthcare environment, allowing physiotherapy to achieve its full potential by embracing both the heightened acuity and complexity of contemporary healthcare.

The biopsychosocial model (BPSM), person-centred care, ‘active’ patient management, and the recent turn towards psychologically-informed physiotherapy, are perhaps the most recent examples [15]. These approaches have struck a chord with many physiotherapists because although they critique some of the passivity of past practices, they are primarily about professional expansion. They embrace the latent humanism of physiotherapy, whilst holding on to the profession’s roots in biomedicine. They show that physiotherapists still know how to fix problems when the patient needs to be more passive (in acute illness or injury, for instance), but can also be responsive and supportive when the client needs to be in charge of their own rehabilitation. They also reflect the truly holistic nature of ‘real’ clinical practice. Hybrid physiotherapy captures the complexity and person-centredness that advocates claim has long been part of the profession, whilst holding on to the rigour and objectivity of more traditional biomechanical physiotherapy.

But there are some significant problems with contemporary hybrid physiotherapy that the chapters in this book hopefully expose. Firstly, hybrid approaches may be encouraging physiotherapists to claim a degree of holism that they are not really entitled to. In almost every example of the biopsychosocial model applied to physiotherapy, for instance, the social aspects of health, including power, gender, class, race and ethnicity, and sexuality; social determinants of health, such as poverty, access, discrimination, environmental degradation, colonisation, employment, and housing; and cultural fields such as the media, economics, history, indigeneity, human and non-human relations, are entirely absent. And even the full existential, relational, and inter-subjective breadth of human psyche is reduced to a set of behavioural and cognitive ‘psychosocial’ variables. Tellingly, these variables reside at the biomedical end of approaches to the human psyche, and sit comfortably alongside other biomedically strong disciplines like cognitive behaviour therapies, acceptance and commitment therapy, the science of brain and behaviour, and the new neurosciences. But these are a world apart from fully subjective, phenomenological, and non-Western approaches to thought and human connection. So claims that hybrid approaches make physiotherapy holistic may be overstated.

Secondly, because hybrid approaches are ‘expansive’, they threaten long-standing territorial alliances with other orthodox professions. To some extent, this is the nature of post-professional healthcare (see Chapter 7), and the end of the functionalist fantasy of healthcare as a cosy alignment of a few elite professions, will be no bad thing. But there is also a distinct risk that all of the established professions may unknowingly embrace the neoliberal ideal of a competitive healthcare marketplace by engaging in a territorial gold rush. Most established professions are now finding inducements to raise their professional prestige by managing higher acuity (usurpation and vertical encroachment from new intensive care paramedics, nurses taking over endoscopy, and podiatric surgery, for example), matched by the need to find solutions for the mushrooming social welfare crisis, caused by the explosion of complex comorbidities and the dearth of medical care in the community. The professions are being pulled, or, perhaps released, from their traditional moorings without a clear sense of who will do what in the future. This has serious implications for patients, who may find future healthcare much harder to navigate.

The growing complexity of healthcare points to the third problem with hybrid approaches, being the ways in which health professional ignore being more patient centred may be a proxy for the late capitalist deconstruction of healthcare. As Bill Hughes suggested;

’there is no doubt that this apparent democratisation of the relationship between professional and patient suited Western governments intent on reducing public expenditure and squeezing the welfare state. The idea of self-care and health maintenance is the layperson’s responsibility rather than the professional became…, in the 1980s, important ideological tools in the privatisation of health care activity’ [16].

In the recent physiotherapy literature, person-centred practice has been interpreted quite specifically as the need for the patients to become less reliant on the therapist, and more focused on self-management [17]. So, rather than understanding person-centred care as a process of democratisation and empowerment — what Hannah Arendt might call ‘action’ — physiotherapists are describing the ‘ideal citizen under neoliberalism’, who is ’autonomous, entrepreneurial, and endlessly resilient, a self-sufficient figure whose active promotion [has] helped to justify the dismantling of the welfare state and the unravelling of democratic institutions and civic engagement’ [18]. Emphasising the patient’s ‘active participation in the planning of their care’ [19], physiotherapists are realising ‘the neoliberal idea of self-responsibility and entrepreneurial decision-making’, alongside its accompanying technologies of neoliberal transformation: evidence-based practice, best practice guidelines, quality management, and hospital at home (ibid).

Perhaps the most important flaw in hybrid approaches to physiotherapy, though, stem from their inability to reconcile biological, experiential, and social philosophies of health. Truly embracing existential understandings of health and illness, or, conversely, grounding oneself in sociological philosophies, cannot be done without fundamentally challenging the basis upon which biological health is measured and understood [20]. Many social theories, for instance, directly contradict biomedical beliefs about causality, truth, and reality, arguing that health and illness are socially constructed. Attempting to absorb or bolt conflicting philosophies on to biomedicine can only work, if practitioners operate only at the most superficial level and don’t really question what their practice is actually doing.

The danger is that hybrid physiotherapy remains ostensibly the same, but now carries with it a veneer of holism: a form of ‘holism-washing’, if you will. In failing to engage deeply with the conceptual depth and plurality of the physical therapies, hybrid approaches risk accelerating the atomisation of healthcare, something we are already seeing with new language around the management of pain, breathing, movement, and some of the profession’s other ‘grand’ concepts. I would argue, therefore, that the hybrid approaches accelerate the neoliberal drift of healthcare, do little to challenge biomedical hegemony, and do little to democratise access to the physical therapies.

- Nicholls DA, Larmer P. Possible futures for physiotherapy: An exploration of the New Zealand context. New Zealand Journal of Physiotherapy. 2005;33:55-60. ↵

- Nicholls DA, Reid DA, Larmer PJ. Crisis, what crisis? Revisiting ‘possible futures for physiotherapy’. New Zealand Journal of Physiotherapy. 2009;37:105-114. ↵

- Nicholls DA. The end of physiotherapy. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge; 2017 ↵

- Nicholls DA, Gibson BE. The body and physiotherapy. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2010;26:497-509. ↵

- American Physical Therapy Association. Impact of student debt on the physical therapy profession. 2020. Available from: https://tinyurl.com/256e7sw6 ↵

- PT in Motion News. Small-scale study finds large-scale debt among recent DPT grads. 2019. Available from: https://tinyurl.com/34m4wjhh ↵

- Shields RK, Dudley-Javoroski S. Physiotherapy education is a good financial investment, up to a certain level of student debt: an inter-professional economic analysis. J Physiother. 2018;64:183-191. ↵

- Pabian PS, King KP, Tippett S. Student debt in professional doctoral health care disciplines. Journal of Physical Therapy Education. 2018;32:159-168. ↵

- Susskind R, Susskind D. The future of the professions. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2015 ↵

- Poggi G. A main theme of contemporary sociological analysis: Its achievements and limitations. British Journal of Sociology. 1965;16:263-294. ↵

- Gubrium JF, Holstein JA. Handbook of interview research: Context and methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2002 ↵

- Traynor M. Foreward. In: Lipscomb M, editor. Social theory and nursing. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge; 2017. p. x-xii. ↵

- O’Byrne P, Holmes D. The politics of nursing care: Correcting deviance in accordance with the social contract. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2009;10:153-162. ↵

- Killingback C, Thompson M, Chipperfield S, Clark C, Williams J. Physiotherapists’ views on their role in self-management approaches: A qualitative systematic review. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 20211-15. ↵

- Mescouto K, Olson RE, Hodges PW, Setchell J. A critical review of the biopsychosocial model of low back pain care: Time for a new approach. Disabil Rehabil. 20201-15. ↵

- Hughes B. Medicalized bodies. In: Hancock P, Hughes B, Jagger E et al., editors. The body, culture and society. Buckingham: Open University Press; 2000. p. 12-28. ↵

- Killingback C, Thompson M, Chipperfield S, Clark C, Williams J. Physiotherapists’ views on their role in self-management approaches: A qualitative systematic review. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 20211-15. ↵

- Chatzidakis A, Hakim J, Littler J, Rottenberg C, Segal L. The care manifesto. London, UK: Verso; 2020 ↵

- Foth T, Lange J, Smith K. Nursing history as philosophy-towards a critical history of nursing. Nurs Philos. 2018;19:e12210. ↵

- Adams TL, Clegg S, Eyal G, Reed M, Saks M. Connective professionalism: Towards (yet another) ideal type. Journal of Professions and Organization. 2020;7:224-233. ↵