21 The origins of the professions

A key principle in understanding the sociology of the professions is the realisation that the professions, as we know them today, are only a very recent invention. They have existed as social entities for only a few decades. And so, in the history of humanity, today’s health professionals are only the most recent, and not necessarily the best, way to manage health and wellbeing.

We know that the professions were few and far between before the Industrial Revolution, which transformed society in Europe and North America during the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries [1]. Clearly, work of all sorts had always been done by people, and human labour has been organised, in some form, for thousands of years. There is even evidence of the organisation of work around various craft guilds, trades unions, and worker’s collectives, dating back to the Middle Ages [2][3]. But the professions are a very distinctive form of social organisation that has only really existed since the 19th century.

Originally, the professions were conceived of as a ‘gentlemanly’ pursuit, with the professions of medicine, law, and the clergy representing ‘an idealised career trajectory for young men, conferring status, applying science and technology in new and interesting ways and assigning immense prestige on a much wider scale’ [4]. In the Western world, the roles of doctor, priest, and lawyer were largely held by independently wealthy men whose interests lay in establishing the prestige of their work, rather than ensuring a stable income and fair working conditions for their peers. Importantly, the work that was done, could not demean the aristocratic gentleman [5], and needed to be distinguishable from more ordinary trades.

This was possible because the early gentlemen professionals did not rely on their work for their living, so could afford to adopt a detached disinterest in its efficacy. If their experiments in professional practice failed, only their interests suffered. For less well-disposed sons of the aristocracy, the challenge was to find work that gave them an income and a way of life that allowed them to remain part of a social circle [6]. But gentlemanly attitudes to work, and even the growth of scientific knowledge after the Enlightenment, cannot explain the sudden growth in the number and range of professions that emerged towards the end of the 19th century. For this, we need to understand the roles played by the Industrial Revolution and early capitalism.

For much of human history, people have lived in small, isolated communities, and their daily toil has been dominated by the need to find and produce food. It would often take all 30 people to produce enough food to feed 30 people. There was rarely any surplus. Everyone, young or old, was involved in the same cycle of seasonal work and there was very little division of labour. Because everything had to be carried by hand, crops, and animals were tended close to the settlement, and so villages often remained small and isolated. People lived precarious lives, often at the mercy of the seasons. Infant mortality was high, and a bad season could decimate the village. This was the pattern of existence for people for thousands of years before the invention of agricultural machinery, and still remains true for billions of people living in low- and middle-income countries today.

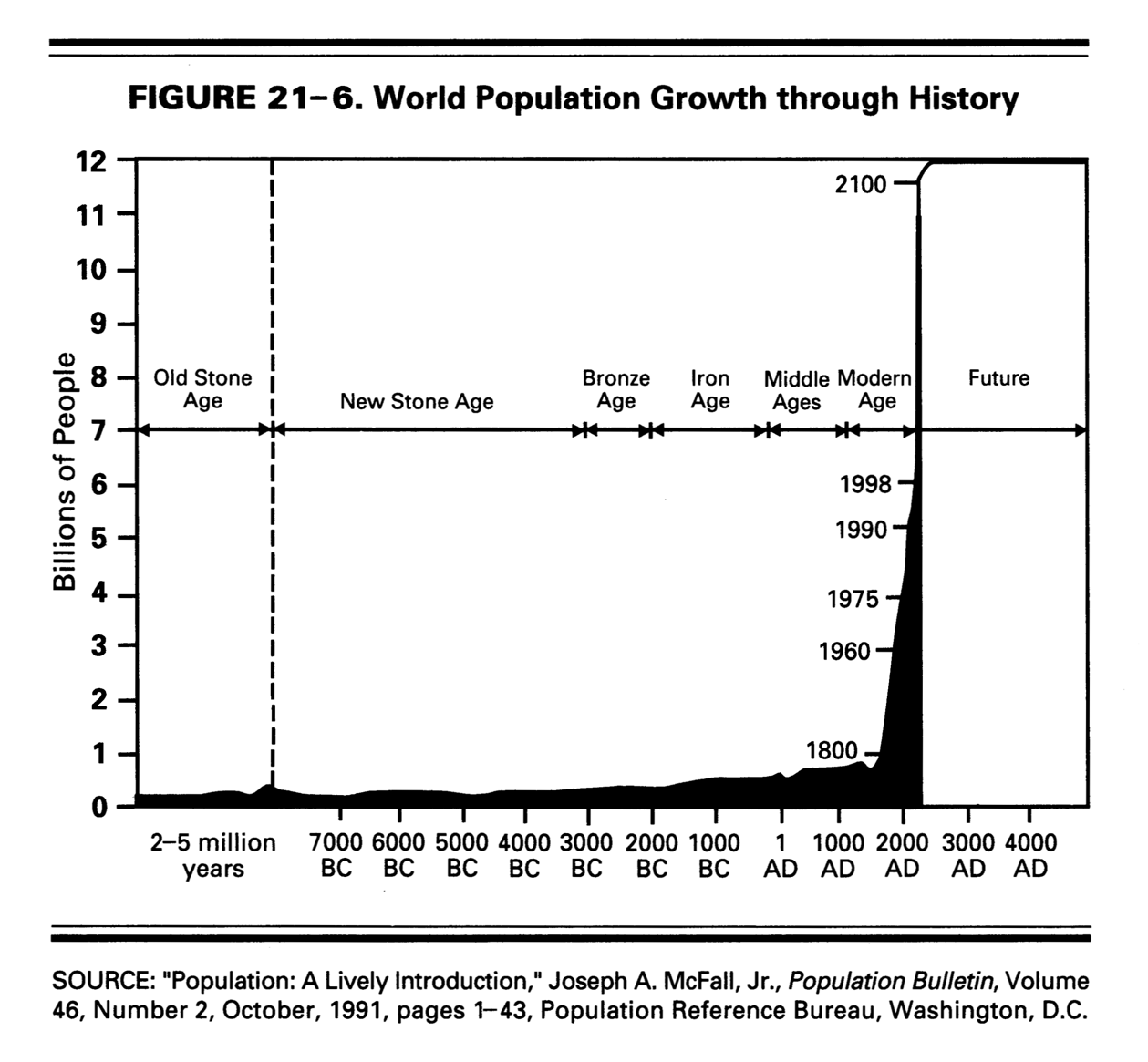

The invention of agricultural machinery in the 17th and 18th centuries, however, changed the picture for many. Now, for the first time, people could grow food miles from the village because they had the machinery to sow, harvest, and transport their crops more easily. Villagers had more food than they could eat for the first time, giving them a surplus that could be stored, to see out a bad season, or be traded for goods and services that the village did not possess. Surplus meant there was less hunger. People rapidly became bigger, healthier, and stronger. Infant mortality rates declined and longevity increased dramatically, leading to a population explosion after 1800.

But the use of agricultural machinery also had another important effect. Villages now needed only one or two people to tend the machines that produced all of the food that had once occupied the whole village. With populations growing rapidly, whole swathes of the rural population now found themselves in need of work. Some took up new skills as blacksmiths, tailors, masons, carpenters, and milliners. But others simply abandoned the countryside in an enormous exodus to the cities.

The invention of the railways at least meant that people could trade their labour wherever they could find work. But there was no more guarantee of work in the rapidly overcrowding cities than in the countryside, and so, within a few decades, millions of people became destitute. The need for work forced some into small business and, although many speculative ventures failed, many succeeded. But for the vast majority of the population, work was scarce and life precarious. And while this precarity was bad for workers and their families, it was a boon for the new industrialists.

The vast oversupply of human labour, and the relative scarcity of work, meant that workers competed for jobs. A business owner given a fixed fee for completing a job, for instance, could tender out parts of the job to workers who would negotiate their own rates of pay. In order to secure employment and feed their families, workers would undercut each other, taking less and less pay for the same work. This drove down the labour costs for the business owner, and increased profits. (There is a beautiful semi-fictional account of this process at work in Robert Tressel’s 1914 book The ragged trousered philanthropists [7], which tells the story of a painting and decorating firm on England’s south coast at the turn of the century. The book has been called ‘the reformist’s bible’ for the way it exposes the injustices faced by everyday workers after the Industrial Revolution.) I will return to this theme shortly, but, suffice to say, the availability of cheap, unskilled labour, drove the mills, foundries, and factories of the Industrial Revolution, and put enormous profits in the hands of a new class of industrialist. How, though, does this relate to the history of the professions?

As well as providing the impetus for early capitalism, the Industrial Revolution created a mass of angry, desperate, and politically active citizens. The revolutions that ensued in the 18th and 19th centuries reshaped societies, and gave birth to modern government. When populations are small, and a feudal system maintains strict divisions between people in society, it is possible to have sovereigns who rule by fear, and exercise what they believe to be god-given power through acts of symbolic violence. But guillotines and public beheadings are little threat to cities teeming with millions of starving, sick, and destitute slum dwellers.

New forms of government were needed that did more than simply suppress unrest. The population needed to be known and understood, and basic services needed to be provided, if people were to stop revolting and contribute, instead, to the prosperity of their country. Nascent governments began to ask who its people were and what they needed. Surveys, censuses, and statistics were used for the first time, and ideas of basic civic rights were mooted. New ideas of ‘citizenship’ and national identity began, tying each person to certain rights and responsibilities. And nation states increasingly saw it as their role to protect their borders, colonise new territory, expand trade, and use these strategies to enhance the health, wealth, and happiness of all of its people.

Clearly, the ‘work’ of these new forms of government could not be done by the handful of elected officials. People were needed to teach children how to be good citizens, heal the sick, maintain law and order, build houses, hospitals, and public works, and defend the country, on a grander scale than had ever been conceived before. And so, a new class of ‘professional’ was created. First, the gentlemanly doctors, lawyers, and priests, were given specific privileges and protections in return for their service to the state. Then, over time, others were added to the professional ranks, in the image of its progenitors. Gradually an infrastructure was built around the professions. In the case of medicine, funding was provided for training and employment, protective legislation was written, hospitals and clinics were built, medical schools established, and the ability to grant their own access rights and privileges was agreed [8][9][10].

Of course, this narrative vastly over-simplified the history of modernisation, and variations can be found in many countries around the world. That notwithstanding, though, the route that most societies have taken from subsistence to modern nation states, has been mirrored wherever the professions have become significant social entities. And Marx and Engels’ work helped to establish the sociological principle that the professions cannot function in a vacuum and need social structures to survive. The reverse has not always been true though, and history has shown us that many societies around the world have functioned perfectly well, for thousands of years, without professionals. The reasons why Western societies established an entire professional class, then, has been of interest to sociologists for decades. And Marx and Engels’ work reminds us how deeply Western professionals are tied to the birth of industrial capitalism and the modern state. Marxian theory has also helped explain some of the unwanted consequences of ‘progress’ in Western societies, and some of these have direct relevance to physiotherapy today.

- Elliot P. The sociology of the professions. London, UK: MacMillan; 1972 ↵

- Farr JR. On the shop floor: Guilds, artisans, and the European market economy, 1350-1750. Journal of Early Modern History. 1997;1:24-54 ↵

- Epstein SR. Craft guilds, apprenticeship, and technological change in preindustrial Europe. Journal of Economic History. 1998;58:684-713. ↵

- Burns EA. Theorising professions: A sociological introduction. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrage Macmillan; 2019 ↵

- Haber S. The quest for authority and honor in the American professions: 1750-1900. Chicago: Chicago University Press; 1991 ↵

- Bucknell C. Wanting legs & arms & eyes. London Review of Books. 2020. Available from: https://tinyurl.com/48thfdv6 ↵

- Tressell, R. (1914). The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists. Grant Richards. ↵

- Millerson G. The qualifying associations: A study in professionalisation. London: Routledge; 1964 ↵

- Millerson G. Dilemmas of professionalism. New Society. 1964;4:15-18 ↵

- Krause E. Death of the guilds: Professions, states, and the advance of capitalism, 1930 to the present. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1996 ↵