Feeding intolerance

Key Concepts

- Clinical manifestations of feeding intolerance

- Gastrointestinal disorders in the neonate

Feeding Intolerance

Intolerance to feeds manifests as the inability of the infant to digest enteral feeding (Gardner et al 2021). It is common among very small preterm infants due to their anatomical, neurological and functional immaturity, with most preterm infants having episodes that require either temporary discontinuation of feeding or a delay in advancing feeding. (Gardner et al 2021). Although most episodes are resolved spontaneously and without sequelae, any signs of feeding intolerance should be regarded as potentially serious because of the increased risk of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) among these infants.

Clinical manifestations

Feeding intolerance can manifest as:

- Vomiting with/without bile

- Large aspirates

- Abdo distension/ increased girth measurements

- Lethargy

- Pale/Mottled

- Discoloured abdomen

- Loose stools / nil stools

(Fanaro 2013, Gardner et al 2021, Kain and Mannix 2023)

Causes

Intolerance to feeding can be:

-

- Physiologic: Gastro oesophageal reflux (GOR), Ingestion of maternal blood- swallowed maternal blood, blood swallowed at birth will eventually clear from the GIT, nipple trauma. If swallowed blood due to nipple trauma, attention must be paid to attachment and lactation, overfeeding, or incorrect positioning of NGT.

- Infection: Systemic- septicaemia urinary tract infection (UTI), meningitis or Local- gastroenteritis

- Intolerance: Cow’s milk protein (this can be transferred through maternal milk if she has diary in her dietary intake)

- Central nervous system: Raised intracranial pressure cerebral oedema, bleed, hydrocephalus, Kernicterus

- Medications: Side effects- caffeine citrate, theophylline, antibiotics, or withdrawal (heroin, methadone)

- Mechanical: Intestinal obstruction, Paralytic ileus, NEC

- Endocrine: Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (rare).

(Fanaro 2013, Gardner et al 2021, Kain and Mannix 2023)

Investigations

To investigate an intolerance to feeding, the following can be considered:

-

- X-ray – air trapping gas not freely through bowel if obstruction

- Left lateral decubitus can determine free air in the intestinal wall or peritoneal cavity

- Barium swallow or enema

- Ultrasound pyloric stenosis

- Aspirates- Ph testing and residual

- Apt testing determines fetal/adult blood

- Stool culture differentiates b/w intestinal lining insult and infection

- Stool Hematest detect occult blood

- Stool Reducing substances: carbohydrate intolerance by detecting reducing substances in the stool

- PH testing 24-hour pH study detects nighttime and intermittent reflux

- Some genetic gastrointestinal disturbances are related to chromosomal/ gene defects

(Fanaro 2013, Gardner et al 2021, Kain and Mannix 2023)

Regurgitation and vomiting

Regurgitation or positing (the effortless return of small quantities of milk), is not uncommon in the first few months of life.

Vomiting is the forceful return of gastric contents. The significance depends on:

- Age

- Frequency, amount

- Characteristics of vomit

- Presence of blood, bile

- Abdominal distension

- Stool characteristics

- Hydration

- Evidence of illness

Vomiting is a concern when there is:

Blood in Vomit – Causes: Maternal blood ingestion, Haemorrhagic Disease of the Newborn (rare with adequate vitamin K), stress ulcers, indomethacin/steroid treatment, upper airway suctioning, or gastroesophageal reflux (GOR).

Bile-Stained Vomit (Green, not Yellow) Concern: Suspect bowel obstruction, particularly if the obstruction is distal to the ampulla of Vater.

Vomit colours indicative of bile present

Unwell Infants –Consider: Infection, inborn errors of metabolism, or congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

Projectile Vomiting –Common Causes: Duodenal atresia or pyloric stenosis.

Failure to Thrive –Potential Issues: GOR.

Gastrointestinal disorders that may be cared for in the SCN

Gastro oesophageal reflux (GOR) Is the spontaneous passage of acidic gastric contents from the stomach into the oesophagus. It is most commonly due to the appropriate relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter. Most GOR is non pathological and requires no treatment beyond explanation and reassurance to the parents. Treatment options may include positioning (Do not position prone because of the increased risk of SIDS), thickening of feeds, Prokinetic agents, Transpyloric tube feeds, Fundoplication, Antacid medications such as Ranitidine and Omeprazole and avoid gastric ‘irritants’ if possible (medications such as Caffeine Citrate can increase the risk of GOR)

Neonatal Bowel obstruction is a condition where there is blockage in an infant’s intestines, preventing the normal passage of stools. This obstruction can occur in either the small or large intestine. Symptoms include abdominal distension, vomiting (often bilious), failure to pass meconium within the first 24-48 hours of life and feeding intolerance. Diagnosis is typically confirmed through imaging studies such as X-rays, ultrasound, or contrast enemas (Hutson et al 2008 Safer Care Victoria 2016). Treatment depends on the underlying cause and severity of the obstruction but may involve surgical correction, such as resection of the obstructed bowel or correction of anatomical abnormalities. Timely diagnosis and intervention are critical for improving outcomes in neonates with bowel obstruction (Hutson et al 2008 Safer Care Victoria 2016).

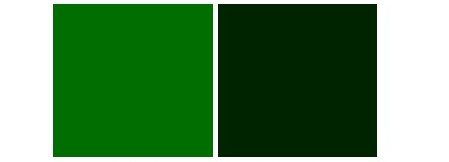

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a serious and life-threatening gastrointestinal (GIT) emergency predominantly effecting the premature population, with a mortality rate of 50 percent (Ginglen and Butki 2023). It is an acquired disorder caused by bacterial invasion of the intestinal wall and is characterised by tissue ischemia followed by necrosis of the mucosal and submucosal layers of the GIT (Ginglen and Butki 2023). Any portion of the bowel can be affected, but damage is predominantly seen in the terminal ileum, caecum and ascending colon. The bowel appears purple and discoloured and is often distended with areas of serosal damage i.e. necrosis and ischemia. Perforation is a late sign and often quite dangerous that requires surgery to avoid further damage & necrosis. Despite recent advances of neonatal intensive care, NEC remains a major health concern in the NICU and an important cause of neonatal morbidity & mortality. Treatment options include resting the gut- nil by mouth, parental nutrition, intravenous antibiotics plus minus surgical intervention.

Prematurity is the most significant risk factor, as immature intestines are more vulnerable to injury. Perinatal asphyxia and respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) can compromise blood flow and oxygen delivery to the gut, increasing the risk. Prolonged rupture of membranes (PROM) may expose the infant to infections that can trigger NEC. Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) can alter blood flow, further compromising gut perfusion. Hypothermia and shock exacerbate poor tissue oxygenation and increase susceptibility. Hematologic factors like polycythaemia, anaemia, and the need for exchange transfusions are also linked to NEC. Epidemic outbreaks in neonatal units can facilitate the spread of infections, while fluid overload can impair gut function and exacerbate intestinal stress (Patel et al 2021 Safer Care Victoria 2016).

Image Attribution and text desctiption

Image is Figure 1. Established risk factors NEC from Bautista GM, Cera AJ, Chaaban H and McElroy SJ (2023) State-of-the-art review and update of in vivo models of necrotizing enterocolitis. Frontiers in Pediatrics doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1161342 licenced CC BY

The image shows risk factors of NEC including prematurity, disrupted mucosal barrier, infection, genetic predisposition, microvasculature alterations, sever anemia, CHD, chorioamnionitis, enteral feeds, impaired immunity, disbiosis and other conditions such as gastroschisis, FGR, HIE and hypoxia.

End of Image Attribution

NEC often presents with both systemic and gastrointestinal signs that can range from subtle to severe. Systemic signs are generally non-specific and may include lethargy, apnoea or respiratory illness, poor feeding, glucose instability, temperature instability, and acidosis. Gastrointestinal symptoms typically include abdominal distension, tenderness, muscular guarding, and abdominal wall erythema. Infants may also present with bloody stools, bilious aspirates or vomiting, and visible loops of bowel. Although many premature infants who develop NEC are initially healthy, feeding well, and growing, a sudden change in feeding tolerance, often indicated by gastric retention, is a frequent early sign. The timing of symptom onset varies and tends to be inversely related to gestational age, with more premature infants showing symptoms later. Early recognition of these clinical signs is crucial for timely diagnosis and management of NEC (Patel et al 2021 Safer Care Victoria 2016).

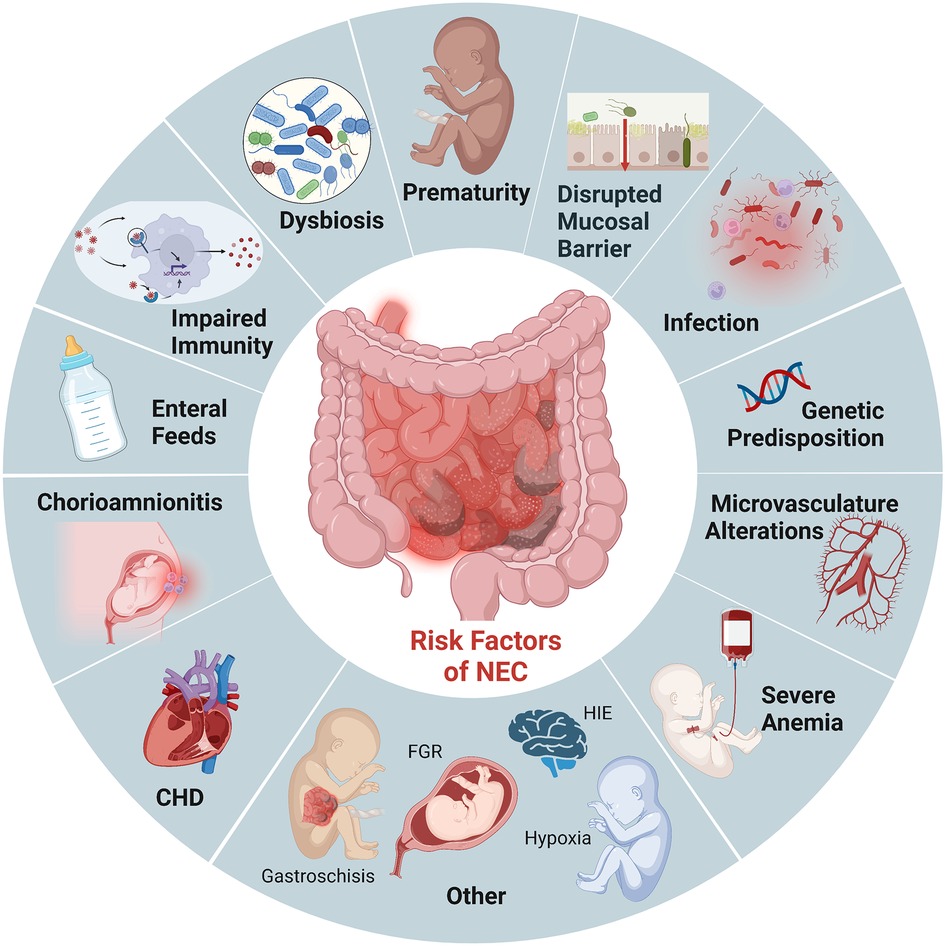

Modified Bells Staging of NEC

In 1986 the Modified Bell staging criteria was introduced as a diagnostic criterion to stage the severity of the disease as shown below: Stage 1 may be cared for in the SCN, Stages 2-3 would more likely be cared for in a NICU

Image Attribution and text description

Image is Figure 1. Summary of the Pathophysiology, Treatment Strategies, and Unknowns of Necrotizing Enterocolitis from Ou, J., Courtney, C. M., Steinberger, A. E., Tecos, M. E., & Warner, B. W. (2020). Nutrition in Necrotizing Enterocolitis and Following Intestinal Resection. Nutrients, 12(2), 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020520 licenced CC BY

Image depicts that intestinal barrier dysfunction leads to increased intestine permeability, inflammation and tissues necrosis. Treatment strategies for Modified Bell’s Stage 1 includes NPO and antibiotics for 3 days.

End of Image Attribution

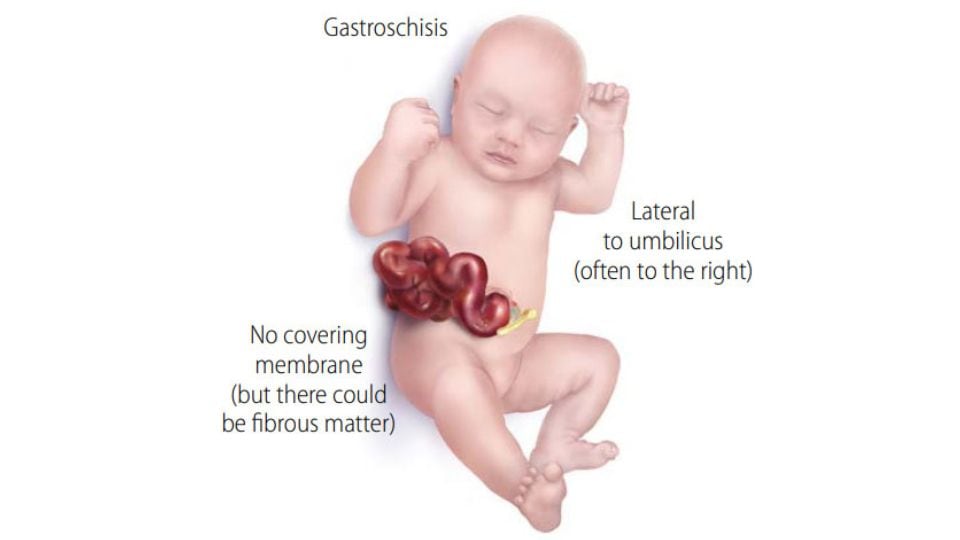

Gastroschisis and Omphalocele

Gastroschisis and Omphalocele are both congenital birth defects of the ventral abdominal body wall in which the abdominal contents are outside the body at birth, however they differ in their location and associated characteristics (Goodwin-Glasser 2024). The exact cause is unclear, but it is believed to be related to early in developmental where the intestines fail to migrate back into the abdominal cavity during the tenth week of gestation (Goodwin-Glasser 2024). Both conditions require immediate medical attention after birth, and surgical interventions are typically successful, although they may involve prolonged care depending on the severity and associated complications.

Gastroschisis usually to the right of the umbilical cord, through which the intestines and sometimes other organs protrude. Surgical repair is required soon after birth to place the organs back inside the abdomen and close the defect. Intensive care may be needed for feeding and infection prevention. Depending on size this may be a staged repair (Goodwin-Glasser 2024, Kain and Mannix 2023).

Image: Gastroschisis by CDC (Public Domain)

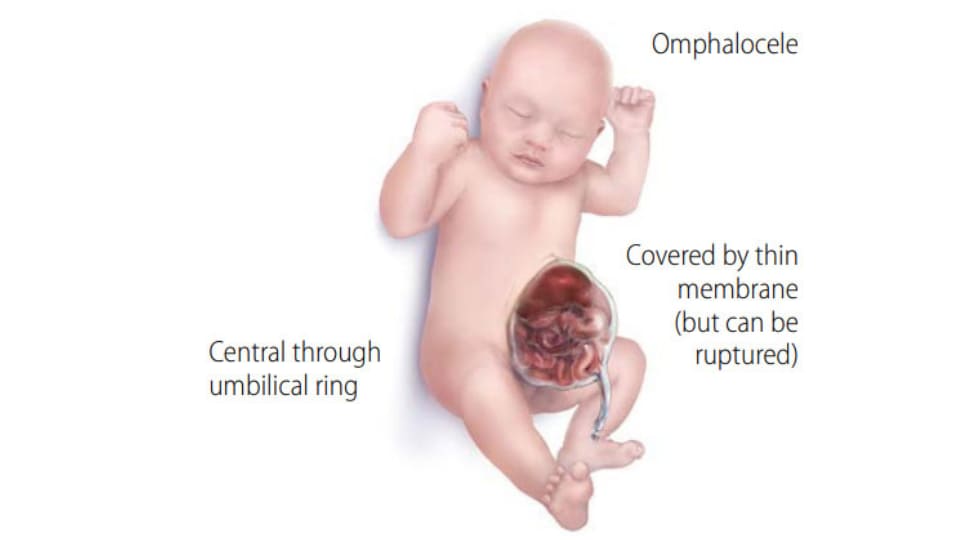

Omphalocele is a congenital defect where the intestines, liver, and sometimes spleen herniate into the base of the umbilical cord and are covered by a protective sac. Surgical repair is required, often in stages if the defect is large. Depending on the size, the organs may need to be gradually returned to the abdomen (Goodwin-Glasser 2024, Kain and Mannix 2023).

Image: Omphalocele by CDC (Public Domain)

In Summary

Neonatal gastrointestinal (GI) conditions are a group of disorders affecting the digestive system in newborns, ranging from mild to life-threatening. Early recognition and management are crucial due to the potential for rapid deterioration. Common conditions include reflux, bowel obstructions, inflammatory diseases, and congenital abdominal wall defects.

-

Gastroesophageal Reflux (GOR) – common and often benign; caused by immature lower oesophageal sphincter.

-

Neonatal Bowel Obstruction – presents with bilious vomiting and distension; causes include atresia, malrotation, or meconium ileus.

-

Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) – serious inflammatory bowel disease in preterm infants, if left undetected or untreated can lead to bowel necrosis.

-

Gastroschisis and Omphalocele – abdominal wall defects; gastroschisis has no sac and higher infection risk, while omphalocele is sac-covered and associated with genetic syndromes.

Test your understanding

References

Bhatia, A., Shatanof, R., and Bordoni, B. Embryology, Gastrointestinal. National Library of Medicine-StatPearls (internet). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537172/

El-Farrash, R., Ibrahim, G., Abdelkader, H., Salem D., and Fahmy S. (2019). Simulated amniotic fluid like solution given enterally to infants after obstructive bowel surgeries: A randomized controlled trial. Nutrition Vol 66 pages 187-191. doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2019.05.001

Fanaro, S. (2023) Feeding Intolerance in the preterm infant. Early Human Development. Volume 89(2) pages S13-S20 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2013.07.013

Gardner, S., Carter, B., Enzman-Hines, M. and Niermeyer, S. (2021) Merenstein and Gardner’s Handbook of Neonatal Intensive Care. 9th Edition. Elsevier.

Ginglen, J., and Butki, N. (2023). Necrotizing Enterocolitis. National Library of Medicine-StatPearls (internet).https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513357/

Goodwin-Glasser, J. (2024) Pediatric Omphalocele and Gastroschisis (Abdominal Wall Defects). Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/975583-overview

Hutson, J., O’Brien, M., Woodward, A., and Beasley, S. (2008) Jones Clinical Paediatric Surgery Diagnosis and Management, 6th ed., Blackwell Publishing

Indrio, F., Neu, J.,Pettoello-Mantovani, M., Marchese, F., Martini, S., Salatto, A., and Aceti, A. (2022). Development of the Gastrointestinal Tract in Newborns as a Challenge for an Appropriate Nutrition: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 14(7). doi: 10.3390/nu14071405

Kain, V., and Mannix, T. (2023). Neonatal Care for Nurses and Midwives. Principles for Practice. 2nd Edition. Elsevier.

Safer Care Victoria (2016). Necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) in neonates. Safer Care Victoria (accessed November 2024). https://www.safercare.vic.gov.au/best-practice-improvement/clinical-guidance/neonatal/necrotising-enterocolitis-nec-in-neonates

Safer Care Victoria (2016). Bowel Obstruction in neonates. Safer Care Victoria (accessed November 2024). https://www.safercare.vic.gov.au/best-practice-improvement/clinical-guidance/neonatal/bowel-obstruction-in-neonates

Sinha, M., Miall, L., and Jardine, L. (2017) Essential Neonatal Medicine. Sixth edition. Wiley and sons

Gastro oesophageal reflux

Nasogastric Tube

Necrotizing enterocolitis