7 Regulation of Mind, Body, Behaviour

Learning Objectives

- Describe core concepts of regulation, including emotion, cognitive and behavioural regulation

- Develop awareness of strategies and skills that health professionals can use to support regulation in service users

- Name the different senses and describe the diversity in sensory preferences among people

- Describe how sensory strategies can be used to support regulation of service users

Introduction

Regulation can involve many complex processes and can occur in many different contexts. Understanding regulation can support your work in health care settings by both equipping you with strategies to maintain regulation in a sometimes busy and demanding environment, but also to support those around you to regulate. Many mental health challenges can impact on a person's ability to regulate, just as we can all relate to experiencing challenges with thoughts, feelings, and behaviour during times of stress. This chapter will provide an explanation of the physiological processes of regulation, as well as an overview of factors that challenge and support regulation.

The body has multiple regulatory systems involving multiple structures with differing functions. Two functions we will cover in this chapter are:

- Self regulation, encompassing emotion, cognitive, and behavioural regulation

- Sensory regulation

Experiencing the broad range of emotions is a normal human experience. Some people have challenges with their experience of certain emotions.

- ADHD

- Borderline Personality Disorder

- PTSD

- Anxiety

- Depression (Easdale-Cheele et al, 2024)

For example, ongoing low mood, sadness and hopelessness is associated with depression (American Psychiatric Association 2024). Others might experience challenges regulating their behaviour and thoughts when feeling certain emotions, such as anger, which can result in subsequent feelings of guilt and shame if the person did or said things that do not align with how they normally wish to behave.

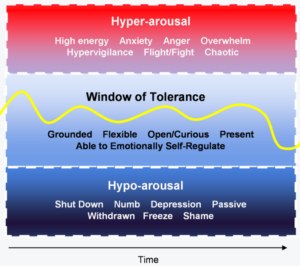

Emotion regulation is commonly used interchangeably with ‘self-regulation’ which more accurately encompasses emotion, cognitive (attention & tone of thoughts), and behavioural regulation.A helpful way to think about regulation is through the ‘window of tolerance’ model, originally developed by Dr Dan Siegal (Hershler 2021); a prominent psychiatrist and author. Dr Dan Siegal developed understandings of how regulation could be altered, as well as supported, for those who had a history of traumatic experiences.

The window of tolerance model suggests that everyone has a ‘window’ within which their regulatory systems can tolerate acute or minor stressors and challenges. Within this window, people are able to tolerate and respond in helpful ways to emotional, cognitive, and behavioural impulses. When a person is ‘tipped outside’ their window of tolerance, i.e. the stressor or challenge they face is such that they are unable to maintain regulation of their thoughts, feelings, and behaviours, they may experience unwanted thoughts, uncomfortable or intense emotions, and unhelpful behavioural impulses (Hershler 2021). When outside the window of tolerance, individuals are considered to be in a state of ‘dysregulation’.

Figure 7. 1 Window of tolerance

[latex]null[/latex]

[latex]null[/latex]Image credit: Psychologytoday.com

Each person will have unique signs of when they are close to tipping outside the window, and also for when they are outside their window (experiencing dysregulation).

Further possible descriptors for the different states include:

Hyperarousal: scattered, jittery, reckless, risky, violent/aggressive

Optimal window: able to consider short term needs and long term goals, reason and make balanced decisions, attune to others, communicate within social expectations

Hypo-arousal: foggy, sluggish, heavy, apathetic (low motivation)

When dysregulated, most people will return to operating within their window of tolerance when given time (as long as no secondary stressors arise). Research has determined that there are some factors which are likely to ‘narrow’ the window of tolerance, i.e. that contribute to people experiencing dysregulation quicker or in the face of relatively small challenges and stressors (Easdale-Cheele et al 2024). These factors include our genetics, childhood environment and experiences, cultural context, as well as any past traumatic experiences (Easdale-Cheele et al 2024; Giroux, McLaughlin & Scheinholz 2019). There are also variable factors that can narrow someone’s window temporarily, such as being tired, hungry, in pain, or experiencing emotional distress (Wagner & Heatherton 2014). These can be common states for people who are encountering health care services, such as when in hospital. This is why it is helpful for health care professionals to understand the signs of when someone is dysregulated, and some strategies that can be used to support regulation.

The rest of this chapter will describe cognitive, behavioural, and emotional regulation, dysregulation, and the influences on each type of regulation, including how health care professionals can generally support the regulation of service users.

Cognitive Regulation

Have you ever found it difficult to maintain your focus or attention on something? Possibly when you have an important test or interview coming up you might find it hard to be present and relax when spending time with your friends. You might be working on a project that is really important and find that while watching TV you have missed parts of the plot because you have started to think about the next steps or possible additions to the project. These are examples of when your cognitive regulation is being challenged. Generally, most people will experience challenges with cognitive regulation when they are experiencing acute stressors (think back to the mental health continuum: at what point of the continuum do you start to notice difficulty regulating the focus of your thoughts?). For some people, the tone of their thoughts also changes, they might notice it is harder to find the positive in a situation, or that they frequently have negative thoughts about their skills and self-worth.

One of the most-researched interventions that can enhance regulation through cognitive practices is mindfulness. Through brain imaging studies, researchers have found that people who engage in mindfulness have increased brain activity in their prefrontal cortex (Wheeler et al 2017)– the part of the brain involved in logic, planning, and judgement. There are a wide range of mindfulness practices and, while a very common practice, it does not necessarily mean listening to a scripted imagery exercise. Mindfulness is a practice that involves careful noticing with an open and curious mind, free of judgement, in the present moment (Wheeler, Arnkoff & Glass 2017).

Example: Mindfulness Exercises to Try

Mindful walking – this exercise is best done outside on a nice day.

Begin by standing still, bringing your awareness to your posture and breathing. Stand up straight and allow your shoulders to relax, gently tilting your face to the sky. Take a few deep breaths, exhaling all the air from your lungs each time. Notice how your body feels in this moment, paying attention to how your feet are planted on the ground. Now gradually begin to walk, noticing the shift in your body weight, the bend in each knee as you lift and place each foot in front of the other. Notice as each bone in your foot makes contact with the ground on each step. Notice any other shifts in your body, a slight swing of your arms, a sway of your shoulders, as you walk on the earth beneath you.

The Centre for Clinical Interventions has a range of self-directed workbooks and exercises. You may also wish to try a mindfulness of emotions exercise on pg. 6 of their ‘Facing your Feelings’ workbook: accessible here (link will open a PDF document).

Gratitude practices have also demonstrated improved mental health outcomes for people, including lower perceived stress and reduced depressive symptoms (including for health care practitioners who engage in the practice; Cheng, Psui & Lam, 2015).

A simple practice that be done daily is finding one thing in your life you are grateful for, one experience you are grateful for, and one personal trait or quality you are grateful for.

Mindfulness also allows us to regard uncomfortable emotional experiences with curiosity, creating some distance from the emotion and discomfort, for us to mindfully consider what is contributing to our reaction and how best to proceed. This can be a very effective skill for health professionals to practice, as their work may involve responding to stressful situations and be fast-paced.

Cognitive regulation has also been demonstrated to play a part in supporting our emotion regulation. Being able to attend (turn our attention) to the important, pleasant, and meaningful parts of our life is going to be helpful for making decisions that lead us towards our goals and that align with our values – both key supporting factors for overall wellbeing and life satisfaction (Corno et al 2018).

Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) is the main intervention used for supporting those who may have challenges resulting from unhelpful patterns of thinking (Beck 2011; Hofmann et al 2012). One of the core tools of CBT is increasing awareness of common thinking patterns, how these impact on a persons emotional experience, and subsequently behaviour. Through regulating their thoughts and using more helpful ways of thinking, the person can achieve more desired or adaptive outcomes in regard to emotions and behaviour (McCreith 2019). For more detail, and a case study on CBT, see the chapter on Psychology, Psychiatry and Health.

There are some health conditions, such as ADHD, that can impact on a person's ability to regulate the focus and tone of their thoughts and impulses (APA, 2022).

DSM-V description of ADHD

“ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder defined by impairing levels of inattention, disorganisation, and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity. Inattention and disorganization entail inability to stay on task, seeming not to listen, and losing materials necessary for tasks, at levels that are inconsistent with age or developmental level. Hyperactivity-impulsivity entails overactivity, fidgeting, inability to stay seated, intruding into other people’s activities, and inability to wait—symptoms that are excessive for age or developmental level. In childhood, ADHD frequently overlaps with disorders that are often considered to be “externalising disorders,” such as oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. ADHD often persists into adulthood, with resultant impairments of social, academic, and occupational functioning.” (APA, 2022).

Behavioural Regulation

Often behavioural regulation is confused with willpower, where it is believed simply having more will can influence our success of following through with a certain behaviour. While our motivation, habits, and environments can all influence our success, or failure, to act in certain ways, behavioural regulation is more about our ability to respond to our impulses in ways that will be helpful for the situation we are in.

Behavioural regulation is strongly linked to impulsivity and activation of the stress-response system. Impulsivity is often thought of as a trait, but we can see as the prefrontal cortex develops (in early adulthood) that impulsivity decreases (Arain et al, 2013). There are also particular skills or strategies that can be employed to reduce impulsivity.

Along with the influence of our environment and any specific conditions impacting on impulsivity, there is also some normal variation in impulsivity even after the prefrontal cortex has been fully developed. Our development of habits and routines, as well as our environment, can support or restrict our ability to respond mindfully to impulses.

Before infants learn etiquette and manners, they commonly throw or simply drop objects they are no longer interested in. This can occur even in the absence of observing others treat objects in this way, indicating it is a basic impulse. We can also observe young children and their impulses when they wish to explore or interact with objects that another is holding. They will often simply reach forward and take the object from the other person, which is often followed by a reprimand or correction from adults in their environment to ask rather than “snatch” objects from another person. While young children learn manners and the expectations for how to interact with objects and those around them from adults and older children in their environment, their success with meeting these expectations and using these new skills is limited by their ability to regulate the basic impulse, which slowly develops over time right up until early adulthood when the prefrontal cortex has finished developing (Arain et al, 2013).

The systems involved in regulating our behavioural impulses are impacted by things like stress, lack of sleep, hunger, and physical pain. Many people find when they are experiencing these states, it is harder for them to refuse enticing treats, to maintain commitments to hard work, study, or physical activity. This is also why health service users may face challenges with regulating their responses and behaviour, as they are likely to be facing physical discomfort due to illness or injury.

To support behavioural regulation in ourselves and others, we can focus on ensuring we take care of our physical needs (pain, hunger, sleep), and practice mindfulness exercises to observe our impulses with curiosity before mindfully proceeding with a helpful action.

If someone is experiencing an intense emotional response, this will also limit their ability to regulate impulses. Some people find when they are dysregulated by intense emotional experiences, their behaviour can put themselves and/or other people at risk. It is important for health care professionals to support others to seek appropriate services that can help address harmful behaviour. Either a psychologist, psychiatrist, mental health clinician, or a GP if there is no specialist available, can support those who are engaging in harmful behaviours.

Australian telephone support services that may be helpful for those experiencing intense emotions and thoughts related to harmful behaviours are listed on the Health Direct website and include the below:

Lifeline text 0477 13 11 14 or chat online Call 13 11 14

Beyond Blue 24 hours/7 days a week or chat online. Call 1300 22 4636

13YARN for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People. Call 13 92 76

Kids Helpline for children and young people aged 5 – 25. Call 1800 55 1800

Emotion Regulation

Emotion regulation is supported by both cognitive and behavioural regulation, however at its core is about the ability to return to a baseline, neutral emotion, following an emotional experience.

What is happening in the brain and body when we feel an emotion?

Our early life experiences have been found to have a great influence on our emotion regulation. There are differences between cultures, as well as within immediate families and more broadly in society, when it comes to ‘norms’ regarding emotional expression and regulation. It is possible you have friends who discuss their emotions openly with their parents and siblings, or maybe you notice that your friends are less expressive than you with emotions such as sadness or disappointment. It can be important for health professionals to reflect on their own experiences, norms, and potential biases surrounding emotional experiences and expression to ensure that you are able to adapt and be non-judgemental in your support of clients and their emotional expression and needs (see the chapter on Reflective Johari-5R Framework, for a model on reflective practice).

Emotion regulation behaviours can be observed very early in infancy, most commonly in the form of self-soothing such as sucking on hands or another item. Babies and children often need support from their environments in order to regulate. This environmental support most commonly comes from adults who are able to co-regulate or support soothing behaviours.

Effective coregulation involves creating a supportive relationship, safe environment, and teaching effective regulation skills through modelling and instruction. Rosanbalm & Murray (2017) provide examples such as:

- Provide a warm, responsive relationship

- display care and affection

- recognise and respond to cues that signal needs and wants

- build strong relationships by communicating, through words and actions, their interest in the person’s world, respect for the person as an individual, and commitment to caring for the young person no matter what (i.e., unconditional positive regard).

- creating an environment that is physically and emotionally safe

- Consistent, predictable routines and expectations to promote a sense of security

- Providing clear goals for behavior regulation, in addition to well-defined logical consequences for negative behaviors.

- Teach and coach self-regulation skills through modeling, instruction, opportunities for practice, prompts for skill enactment, and reinforcement of each step towards successful use of skills.

Co-regulation

Co-regulation: “a supportive process … that can occur within the context of caring relationships across the lifespan… that fosters self-regulation development (Rosanbalm & Murray 2017, pg. 1)”.

“To co-regulate successfully, caregivers will need to:

- Pay attention to their own feelings and reactions during stressful interactions with a child, youth, or young adult.

- Pay attention to their own thoughts and beliefs about the behaviors of others.

- Use strategies to self-calm and respond effectively and compassionately.

Caregivers greatly benefit when they take a moment for some deep breaths or self-talk. When a caregiver responds calmly to a child, youth, or young adult, it helps to keep the young person’s feelings from escalating and also models regulation skills.”

Some of the first skills that children learn in emotion regulation is developing a vocabulary to describe their emotional experience. That is, naming what they are feeling. Studies have also shown that by naming our emotions, people of all ages are able to reduce the intensity of their emotional experience and responses (Levy-Gigi & Shamay-Tsoory 2022). As health professionals, we can help our clients to name their emotions by reflecting back what they have said or how they are behaving, which might indicate they are experiencing a particular emotion.

Case Example

Mr Gerrard had a fall in his home and broke his hip. He has been otherwise healthy most of his life and this is his first time having a hospital stay. His posture appears tense and he is constantly watching the various people pass by his door each day. He is hesitant to move about too much and reports finding it difficult to pay attention to the newspaper, something he normally reads as part of his morning routine.

Health care worker: “Mr Gerrard, you appear tense and are finding it difficult to pay attention to your newspaper, I wonder if there is something worrying you?”

Mr Gerrard: “all of this is unfamiliar, I just want to make sure things are right at home. It’s stressful not knowing what is going on”

Health care worker: “it’s understandable to feel stressed, you are in an unfamiliar environment and aren’t able to take care of things at home like you normally would. Maybe we can see if the social worker can help you to get in contact with people who can help out at home and reassure you that things are under control?”

This is an example of the health care worker noticing and brining awareness to the clients’ emotional experience, which lead Mr Gerrard to feel comfortable to express how he was feeling “stressed”. The health care worker then validated Mr Gerrard’s experience by being non-judgemental and viewing his emotional experience as a reasonable reaction to the situation he was in (this specific technique is called normalising). After validating the emotional experience, the health care worker then made a suggestion for how they could tackle the situation that was causing stress and worry.

Sometimes, we can’t adjust or control the situation that is giving rise to uncomfortable emotions, it’s usually in these situations that we need to focus on addressing the emotion or using particular coping strategies to reduce the intensity of our emotional experience.

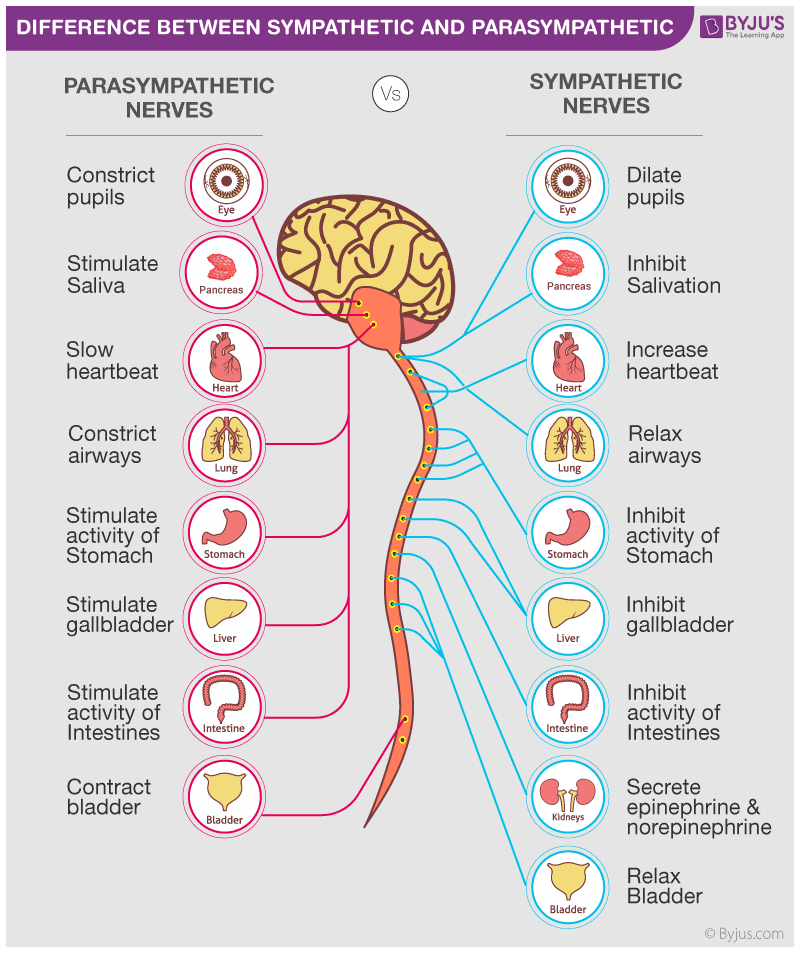

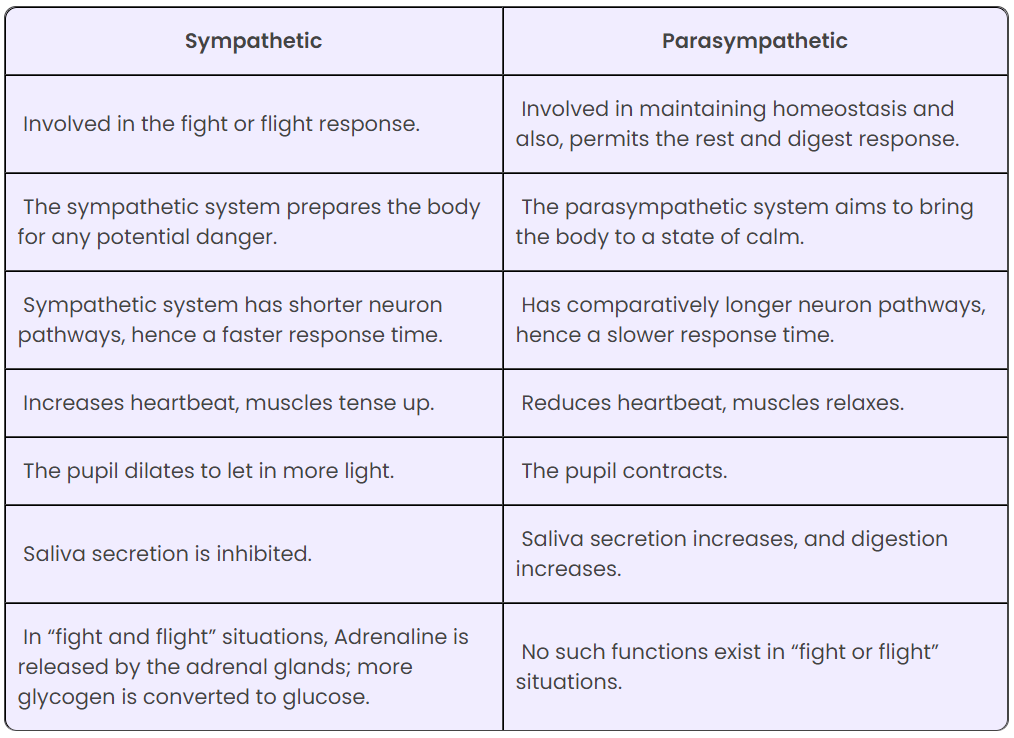

When people are experiencing intense emotions, such as fear, different parts of the brain activate, and our prefrontal cortex “goes offline”, this is called the ‘stress response’. When our stress response is activated, there are a range of physiological processes set off by our ‘sympathetic nervous system’, which can result in feeling shaky, having a dry mouth, increased heart rate, and sometimes even feeling sick in the stomach.

Sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system structures and functions

Image credit: Byjus.com

When the stress-response system is activated, people are also more likely to be impulsive. This is when people are acting from a place of feeling threatened and their impulses are attempting to keep them safe, although not always in ways that are helpful for the situation. These are the behaviours that are often categorised as ‘fight, flight, or freeze’, it can also be incredibly hard for the person to use logic and reason.

In these situations, a person is in a state of ‘dysregulation’ – where their emotion and stress response systems are unable to bring the persons’ state back to baseline. In these moments, another person co-regulating and supporting the person to engage in regulation strategies is incredibly helpful.

Regulation strategies for the fight, flight, and freeze response

When someone’s stress response is activated, they might need extra help to regulate. Before a person is able to regulate their thoughts and clearly think through the situation in order to choose helpful behaviours, they may need to take action to help their nervous system regulate. These particular strategies are often termed ‘Grounding Strategies’ as they assist people to pay attention to the here and now, i.e. the things going on around them, rather than focusing on the uncomfortable emotional experience and internal sensations that might accompany it – which often gives rise to unhelpful thinking.

Examples of grounding strategies

- Name 5 things you can see, 4 things you can hear, 3 things you can touch, 2 things you can smell and 1 thing you can taste

- Breathing at a particular pace; breathe in for 7 counts, hold the breath for 4 counts, breathe out for 7 counts, pause for 4 counts and repeat for a total of ten cycles

- Mindfulness body scans, paying attention to the feeling of your feet on the ground, and noticing other points where your body makes contact with a surface

- Using a cold flannel on the forehead or dipping the face in cold water – this activates the ‘dive reflex’ which can immediately slow our breathing and heart rate

- Progressive muscle relaxation, an exercise where you squeeze individual parts of the body – starting with the toes, holding for 5 seconds before completely relaxing this part of the body, repeating each body part 3 times

(for more strategies that can help regulation, see ch. 3 ‘the mind-body link’ from earlier in this text)

Grounding strategies are usually short, simple steps that people can remember and follow to redirect their attention, and stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system – the part of our nervous system that dampens the stress response. Once a person has been able to regulate their stress response, they are then going to be more able to engage in acknowledging and responding to their emotional experience, as well as the situation they are in, in helpful ways.

Sensory Regulation

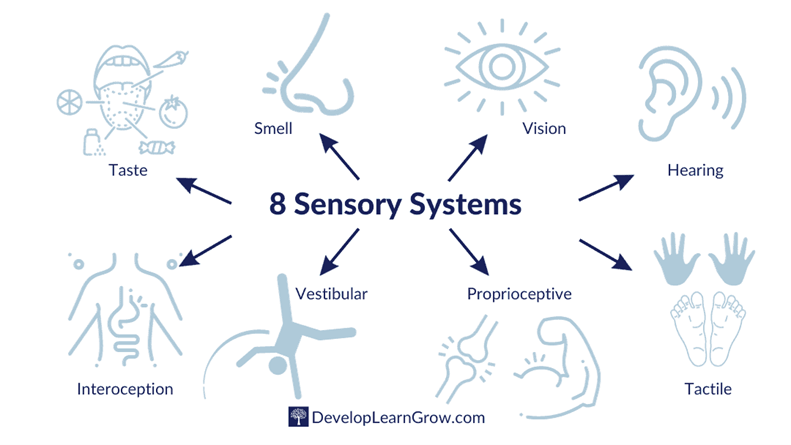

Many people know of the 5 senses, but we actually have an additional 3 senses that many don’t know about.

Image credit: 8 Sensory Systems by Develop Learn Grow. © Amy Hathaway, further reproduction requires permission of the copyright holder.

Each of these systems has special receptors that register particular stimuli and send this information back to our brain, for us to consider, make sense of, and respond to if needed. For example, the smell of smoke – an acrid and strong smell, is often perceived as alerting and immediately brings our attention to this stimuli. We may be able to detect even very faint smells of smoke more readily than other more mild smells such as dampness.

Information from all 8 senses helps us to know where our bodies are in space, orient us to our surrounding environments, and help us to regulate our alertness and attention in order to better respond to our environment and the occupations we may be participating in.

The 3 less-commonly known senses

Vestibular: the sensory receptors in our vestibular system help us to keep our balance by telling us where our head is in space. It is the conflicting information received from our vestibular system and visual system when focusing on a fixed object, such as writing in a book, while riding in a car that contributes to the experience of motion sickness that many have experienced.

Proprioceptive: Our proprioceptive system works alongside of our vestibular system to help us identify where our body is in space. Our proprioceptive system will allow us to make sense of our body positioning even when it is not in view, e.g. knowing that our legs are bent underneath a desk, or knowing that our hand is clenched when it is down at our side.

Interoception: This is the word given to our ability to perceive internal sensations, such as butterflies in the stomach when feeling anticipation or nerves, or a rumbling and empty stomach when we are hungry. It is often our interoception, and the information received through this sensory system, that helps us to identify our emotional state. For example, feeling tense, flushed, and hot might signal that we are angry.

Under and over-stimulation

When our sensory systems are receiving too little information (stimuli), we may feel agitated, lethargic, or foggy and have trouble attending to our surroundings or tasks – this is when we are under-stimulated. When we are overstimulated, our sensory system is receiving too much information and we may feel overwhelmed and scattered. We can consider our sensory environments to contribute to, and impact on, our window of tolerance. For example, if someone is in an environment that has lots of competing or intense sensory stimuli (think of a busy and noisy restaurant), they may have a narrower window of tolerance and find it difficult to regulate their attention, emotions, and/or behaviour. What is too little or too much stimuli will be different person to person and dependent on their sensory profile.

Sensory Profile

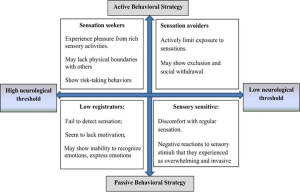

Occupational Therapist, Winnie Dunn, developed the Model of Sensory Processing. The model considered four quadrants of sensory processing, two categorising a persons’ general response to stimuli; either active or passive, and two categorising the persons’ threshold of stimuli; low, or high.

Dunn also developed assessments of sensory processing that have been standardised for the adult and child/adolescent populations. Through completion of the Adult Sensory Profile, a person will be rated as “much more than, more than, equal to, less than, or much less than” than the average person without a medical condition for each quadrant.

In the figure above, are descriptors for the extreme end of each of these quadrants. Each profile; sensation avoiding, sensory sensitive, low registration, and sensation seeking, sits on the aforementioned scale of “much more than” to “much less than”. Meaning, someone may rate as sensory avoidant “more than” the average adult but find their avoidance behaviours are not extreme, such as simply avoiding the supermarket at busy time periods. An individuals’ rating in each of these quadrants can also be dependent on the type of sensory stimuli being received, e.g. a person may present as sensory seeking for vestibular input, but sensory avoidant for auditory input.

Sensory Preferences

Our sensory preferences are much like our personal preferences for taste. Some will prefer sweet over savoury, some like lots of spice, others prefer milder flavours.

We will likely have our own preferences across the different sensory systems, and in conjunction with our sensory profile will give rise to our unique experiences of sensory stimuli as either pleasing or unpleasant.

How to use the senses to support regulation of service users

Fidget tools; these can provide pleasant sensory stimuli, such as bright colours, predictable and rhythmic motion, pleasant textures, sounds, and help people to maintain alertness in environments that may not have a lot of other stimuli, e.g. quiet waiting rooms.

Be mindful of the environment and changes that can make the environment a better fit for the service user, e.g. dimming lights, not having TVs or turning them on mute, not having a bell over the door if the environment is generally very busy with lots of people moving in and out.

Encouraging service users to bring objects from calming environments, such as home, that they can use to engage with mindfully – e.g. a soft blanket, a photo of a pet or positive memory, scented oils or creams.

Generally calming activities; warmth and deep pressure such as a heated wheat bag or weighted item are generally calming to most people (note: there are guidelines for the safe use of weighted items and this should be done in consultation with a professional who has knowledge of the sensory system and evidence-based practice for use of weighted items, such as an occupational therapist).

Sensory rooms; are rooms designated for people who may need a break from the wider environment, where they can safely and privately engage in sensory regulation activities such as listening to quiet music in a bean bag, or rocking on the floor. See the chapter on Occupational Therapy and Psychosocial Wellbeing to learn more about sensory rooms and their use in mental health services.

Summary

An individuals' ability to regulate their thoughts, feelings, and behaviour is influenced by many factors. This can include their environment, their internal state such as hunger, pain, and fatigue, their sensory profile, any particular diagnoses, or traumatic experiences.

Everyone can experience challenges to remaining within their window of tolerance, and when tipped into the extreme, will experience dysregulation. When dysregulated, the sympathetic nervous system is activated and results in physiological responses such as increased heart rate, breathing, and changes to blood flow within the body.

When dysregulated, people may experience unwanted and unpleasant thoughts, feelings, and behavioural impulses. Mindfulness exercises have demonstrated effectiveness for helping people to regulate their thoughts and attention and can be practiced daily or used as grounding techniques when experiencing challenges to regulation. Health care professionals can assist people to regulate strong emotions by helping service users to identify and name the emotion, and through coregulation. Other methods of regulating include techniques that activate the parasympathetic nervous system such as breathing exercises, and progressive muscle relaxation. Modifying the environment, and engaging with particular calming sensory stimuli can also assist a person to regulate. This is best done by a professional who is able to assess and interpret someone’s sensory profile or who is trained in environmental assessment and the sensory systems, such as an occupational therapist.

Reflection Exercises

Window of tolerance: think of your own signs and descriptors that indicate when you are in each state of hyper, hypo, and optimal arousal

Research activity: Borderline Personality Disorder has a long history of being stigmatised in the health sector. Using an online search engine, see if you can find a video, blog post, or academic text that describes a person’s lived experience of borderline personality disorder. Identify any experiences of stigma that they describe and discuss how health professionals might avoid perpetuating stigma of people who have this diagnosis.

Role Play: Have one person play the role of a dysregulated service user (think of a scenario that is relevant for your area of study). The other person is to play the role of health professional who will support the service user through coregulation. Consider how you might implement each of the suggestions provided in this chapter.

Reflection activity: thinking about your own preferences, identify three things you find calming and three alerting sensory exercises or experiences. Challenge yourself to find something across multiple different sensory systems.

How and when might you use these to support your regulation? E.g. are there common experiences where you feel close to hyperarousal and one of the calming activities would be helpful for maintaining your window of tolerance?

References

American Psychiatry Association. (2022). Neurodevelopmental Disorders in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787.x01_Neurodevelopmental_Disorders

Arain, M., Haque, M., Johal, L., Mathur, P., Nel, W., Rais, A., Sandhu, R., & Sharma, S. (2013). Maturation of the adolescent brain. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 9, 449–461. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S39776

Brown, C., Steffen-Sanchez, P., Nicholson, R. (2019) Sensory Processing. In Brown, C., Soffel, V., Munoz, J. (Eds.). Occupational Therapy in Mental Health: A Vision for Participation (2nd ed). F.A. Davis.

Champagne, T. (2011) Sensory Modulation & Environment: Essential Elements of Occupation (3rd ed). Pearson.

Corno, G., Etchemendy, E., Espinoza, M., Herrero, R., Molinari, G., Carrillo, A., Drossaert, C., & Baños, R. M. (2018). Effect of a web-based positive psychology intervention on prenatal well-being: A case series study. Women and Birth, 31(1), e1-e8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2017.06.005

Easdale-Cheele, T., Parlatini, V., Cortese, S., & Bellato, A. (2024). A Narrative Review of the Efficacy of Interventions for Emotional Dysregulation, and Underlying Bio–Psycho–Social Factors. Brain Sciences, 14(5), 453. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3425/14/5/453

Levy-Gigi, E., & Shamay-Tsoory, S. (2022). Affect labeling: The role of timing and intensity. PloS one, 17(12), e0279303. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279303

Rosanbalm, K.D., & Murray, D.W. (2017). Caregiver Co-regulation Across Development: A Practice Brief. OPRE Brief #2017-80. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, US. Department of Health and Human Services

Wheeler, M., Arnkoff, D., & Glass, C. (2017). The Neuroscience of Mindfulness: How Mindfulness Alters the Brain and Facilitates Emotion Regulation. Mindfulness. 8. DOI 10.1007/s12671-017-0742-