5 Stigma in Mental Healthcare

Learning Objectives

- Identify how language and labelling contribute to mental health stigma and discrimination.

- Understand the impact of stigma on mental health care access and patient outcomes.

- Examine the role healthcare professionals play in either perpetuating or addressing stigma.

- Develop strategies to reduce stigma by incorporating the voices of individuals with lived experience.

Introduction

Stigma surrounding mental health remains a pervasive barrier to individuals seeking care and achieving recovery. It affects not only those living with mental health conditions but also influences how healthcare professionals perceive, engage with, and deliver care. Stigma perpetuates misconceptions, creating obstacles to accessing services, contributing to discrimination, and leading to social exclusion (National Mental Health Commission, 2024). This chapter explores the concept of stigma, examining its complex impact on healthcare access, treatment outcomes, and the professional responsibilities of healthcare providers. It further discusses strategies healthcare professionals can adopt to combat stigma through culturally competent, trauma-informed, and compassionate care, as well as their role in advocacy and policy reform aimed at creating an inclusive and supportive healthcare environment.

Understanding Stigma in Mental Health

Stigma encompasses negative attitudes, beliefs, and discriminatory behaviours directed toward individuals with mental health conditions, leading to social exclusion, marginalisation, and diminished quality of life (Jackson-Best & Edwards, 2018). It is crucial for healthcare professionals to understand the multifaceted nature of stigma, as it creates barriers to accessing care, exacerbates conditions, and impedes recovery. Healthcare professionals are uniquely positioned to address these barriers. By actively challenging stigma, they can foster a more inclusive, equitable, and compassionate healthcare environment (Dockery et al., 2015).

To deepen understanding, stigma can be further categorised into different types and analysed.

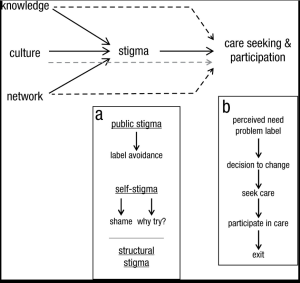

Types of Stigma

Public Stigma: This involves negative societal attitudes and discriminatory behaviour towards individuals with mental health conditions. Such stigma can be perpetuated through media portrayals, public misconceptions, and cultural stereotypes. Healthcare professionals must recognize the impact of public stigma on patients’ willingness to seek help and adhere to treatment plans (Reavley & Jorm, 2012).

Self-Stigma: When individuals internalise societal stigma, they experience shame, reduced self-esteem, and reluctance to seek help. This self-stigmatisation is particularly harmful as it can hinder recovery and exacerbate symptoms. Healthcare professionals should be trained to identify and address self-stigma, providing interventions that enhance self-esteem and resilience (Corrigan, Druss, & Perlick, 2014).

Structural Stigma: Structural stigma refers to the policies, practices, and institutional behaviours that restrict opportunities and access to services for people with mental health issues. Examples include inadequate insurance coverage for mental health treatments or discriminatory hiring practices that impact those with a history of mental illness. Healthcare systems must address structural stigma by advocating for equitable policies and improved access to care (Corrigan et al., 2020).

Courtesy Stigma (Stigma by Association): Healthcare professionals and family members of individuals with mental health issues may also experience stigma due to their association with those living with mental illness. This type of stigma can deter families from seeking help for loved ones. Educating and supporting families and healthcare providers is crucial for overcoming courtesy stigma and improving support systems for patients (Phelan et al., 2021).

Figure 5.1 Matrix describing the stigma in mental illness (extracted from Corrigan,Druss & Perlick, 2014)

The Impact of Stigma on Patient Engagement

Stigma significantly delays help-seeking behaviour, resulting in prolonged periods of untreated conditions. This effect is particularly pronounced in marginalized groups such as Indigenous Australians, refugees, individuals from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) backgrounds, and LGBTQI communities. These populations often experience “double stigma” due to both their mental health condition and their identity. Healthcare professionals must be aware of these additional layers of stigma and adopt culturally tailored approaches that work collaboratively with these communities to build trust and facilitate access to mental health services (National Mental Health Commission, 2024).

Example: Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians face a high burden of mental health challenges, compounded by cultural, historical, and social factors. The legacy of colonisation, displacement, and intergenerational trauma contributes to higher rates of depression, anxiety, and substance abuse disorders. Healthcare professionals working with Indigenous communities must integrate culturally sensitive approaches, such as engaging with Elders and community leaders, to build trust and deliver culturally appropriate interventions (Gee et al., 2014). Incorporating traditional healing practices alongside clinical care may improve engagement and outcomes.

The Role of Healthcare Professionals in Stigma Reduction

Healthcare professionals are in a unique position to either perpetuate or challenge stigma. Diagnostic overshadowing, where all patient symptoms are attributed solely to a mental health diagnosis, is a common issue that can lead to misdiagnosis and inadequate care. Comprehensive assessments must be conducted to ensure that all aspects of a patient’s well-being are considered, avoiding stigmatising assumptions that could harm patient outcomes (Rodger, 2019).

Key Strategies for Healthcare Professionals:

Use of Person-Centered Language: Avoiding derogatory terms like “crazy” or “insane” and using respectful language such as “a person experiencing schizophrenia” rather than “a schizophrenic” emphasises the individual beyond their diagnosis, promoting dignity and reducing stigma (Henderson et al., 2014).

Reflective Practice: Regular clinical supervision, reflective practice, and professional development are essential for recognising and addressing biases. Journals, peer supervision, and group debriefing sessions can help healthcare workers identify instances where stigma may have influenced their approach to care (Snowdon,Laggat& Taylor,2022).

Collaborative Care Models: Engaging patients as partners in their treatment plans promotes a sense of autonomy and empowerment. By involving patients in decision-making processes, healthcare professionals can challenge stigma and support self-determination (Hamm et al., 2018).

Culturally Competent Care as a Stigma Reduction Strategy

Cultural competence is critical in providing effective mental health care, particularly in multicultural societies such as Australia. Healthcare professionals must recognize how cultural beliefs and values influence the perception and stigma of mental illness. For example, in some cultures, mental illness may be perceived as a sign of spiritual imbalance or moral failure, leading to reluctance in seeking help. Addressing these cultural nuances through culturally competent care is essential.

Practical Steps for Culturally Competent Care:

Engage with Cultural and Community Leaders: Collaborating with leaders and community members to understand cultural perceptions of mental health helps develop trust-based care strategies. For instance, involving community leaders in health promotion activities can improve the credibility and acceptance of mental health services.

Adapt Communication Strategies: Using culturally appropriate language and interventions that resonate with the patient’s background ensures that care is accessible and respectful. Healthcare professionals should be trained in cultural communication techniques, such as using interpreters and cultural liaisons when needed.

Incorporate Family and Community Support Systems: In cultures where collective well-being is prioritised, interventions should be designed to include family engagement, as this can support recovery within cultural contexts. For example, family-centered therapy can be effective in communities where family approval is crucial for treatment adherence.

Evidence-Based Interventions for Stigma Reduction

Education and Training Programs

Continuous education programs for healthcare professionals are crucial in reducing stigma. These programs should focus on empathy, trauma-informed care, and person-first language to shift attitudes and build professional competence (Henderson et al., 2014). Training modules could include:

- Workshops on Implicit Bias: Interactive workshops can help healthcare workers recognise their biases and provide strategies for managing them in clinical settings.

- Trauma-Informed Care Training: This approach helps professionals understand how trauma affects mental health and behaviour, enabling them to respond empathetically and avoid retraumatising patients (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment ,2014).

Public Health Campaigns

Collaborative efforts between healthcare providers and public health organisations can improve mental health literacy. Campaigns should provide clear, evidence-based information to reduce fears related to dangerousness and unpredictability associated with mental illness (Reavley & Jorm, 2012). Examples of successful campaigns include Beyondblue, which has significantly increased public awareness and acceptance of mental health issues.

Integration of Lived Experience Narratives

Incorporating stories from individuals who have experienced mental health issues and recovery into training materials humanises mental health conditions and offers practical insights for healthcare workers (Dockery et al., 2015). These narratives challenge stereotypes, promote empathy, and demonstrate recovery as a realistic outcome.

Long-Term Strategies for Stigma Reduction in Healthcare Settings

Implementation of Trauma-Informed Care Practices

Trauma-informed care emphasises the importance of safety, trust, choice, collaboration, and empowerment. Adopting these practices helps professionals understand and respond to patients’ behaviours with empathy, reducing stigma and promoting patient-centred care (Corrigan et al., 2019).

Practical applications include:

Environmental Modifications: Creating safe spaces in healthcare facilities that respect patient privacy and autonomy.

Policy Integration: Incorporating trauma-informed principles into organisational policies, ensuring that all staff are trained and supported in trauma-informed practices.

Policy and Structural Reforms

Advocating for policy changes that address structural stigma within healthcare systems is vital. Professionals can support initiatives that promote equitable access to mental health services, integrate cultural competence training, and eliminate discriminatory practices (National Mental Health Commission, 2024).

Workplace Mental Health Programs

Developing programs that support healthcare professionals’ mental health is essential. Reducing stigma within the workforce encourages professionals to seek help and creates a culture where mental health is openly discussed without fear of judgment (Henderson et al., 2014). Examples include peer support groups, mental health days, and confidential counselling services.

Practical Steps for Healthcare Professionals: Actionable Approaches

Promote Early Intervention and Education: Integrate mental health awareness and stigma reduction education into routine healthcare services. This includes implementing screening programs that normalise mental health check-ups similar to physical health assessments.

Model Inclusive Behaviour: By modelling stigma-free behaviour, healthcare professionals set a precedent for patients and colleagues alike. This includes actively dispelling myths about mental illness during patient interactions and advocating for inclusive practices within the healthcare team.

Engage in Policy Advocacy: Healthcare professionals can play a crucial role in shaping policies by advocating for changes that reduce barriers to care and increase resources for stigma reduction programs(Corrigan, Druss & Perlick,2014).

Future Directions: Building a Stigma-Free Healthcare Environment

Healthcare professionals are critical in building a stigma-free environment, not just within healthcare settings but also in broader society. Long-term efforts must integrate education, policy reform, and community partnerships. Programs should be evaluated and adapted continuously to remain effective and relevant to Australia’s diverse population. Collaborative research efforts are needed to identify the most impactful strategies, ensuring sustained progress in combating stigma (Corrigan, Druss, & Perlick, 2014).

Summary:

Healthcare professionals have a responsibility to actively reduce stigma through empathetic, informed, and inclusive practices. By embracing cultural competence, trauma-informed care, and evidence-based education, professionals can transform stigma into understanding, significantly improving mental health outcomes across Australia. Efforts to combat stigma must be sustained, dynamic, and inclusive, ensuring that all individuals, regardless of background, have access to equitable and compassionate mental health care.

Reflective Activities

Scenario 1:

Emily is a 35-year-old woman who has been experiencing symptoms of depression for several years. Despite feeling overwhelming sadness and fatigue, she has avoided seeking help due to the stigma she associates with mental health conditions. Emily works in a high-pressure corporate environment, where mental health issues are often seen as a sign of weakness. She has internalized this belief and fears that if her colleagues or boss find out about her struggles, it will affect her career.

When Emily finally visits her primary care physician, she describes persistent headaches and fatigue but does not mention her mental health struggles. Her doctor, aware of the prevalence of mental health stigma, gently encourages Emily to talk about how she’s been feeling emotionally. Emily opens up about her feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and isolation. However, she expresses fear about being judged and viewed differently if she seeks mental health support.

The physician uses person-first language and reassures Emily that mental health conditions are common and treatable. Together, they develop a plan that includes therapy, medication, and workplace accommodations. Emily is encouraged to take small steps to improve her mental health and given resources for mental health support groups.

Questions:

- How might the stigma Emily faced in her workplace have contributed to her delay in seeking mental health care? Reflect on the societal and workplace factors that may have reinforced Emily’s reluctance to get help.

- How did the physician’s use of person-first language impact Emily’s willingness to discuss her mental health? Consider how language can create a safe, non-judgmental environment in clinical settings.

- What role does self-stigma play in the delay of seeking treatment, and how can healthcare professionals address this with patients? Reflect on how Emily’s internalised stigma affected her health-seeking behaviour and what strategies healthcare workers can use to reduce self-stigma in patients.

- In what ways could the healthcare system better support individuals like Emily, who are reluctant to seek care due to stigma? Consider systemic changes that could improve access to mental health care and reduce barriers related to stigma.

Scenario 2:

Maria is a 42-year-old woman from a tight-knit, traditional community where family honour is highly valued. For years, she has been struggling with anxiety and depression but has never sought professional help because, in her culture, mental illness is seen as a personal weakness or spiritual failure. She believes that admitting her struggles will bring shame to her family, and her community discourages open discussions about mental health.

Maria’s condition has worsened, and she is now experiencing frequent panic attacks and overwhelming sadness. Her family is unaware of the severity of her struggles because Maria tries to hide her symptoms, fearing their reaction. She eventually visits a healthcare provider, but she is hesitant to talk about her mental health, focusing only on vague physical symptoms like headaches and fatigue.

As a healthcare professional, it is important to recognize the cultural beliefs influencing Maria’s reluctance to discuss her mental health openly. Understanding her cultural background can help you tailor your approach and create a safe space for her to explore her mental health without fear of judgment.

Questions

-

- How can you apply cultural competence to better understand Maria’s hesitations and fears about discussing her mental health?

- What strategies could you use to foster trust and reduce the stigma that Maria may feel within the context of her cultural beliefs?

- How can you incorporate thoughtful language and culturally sensitive interventions to encourage Maria to seek further help and support?

- Reflect on how language used in your clinical setting may contribute to stigma. How can you adopt more inclusive and person-first language?

- Think about a time when you witnessed stigma in healthcare. What could have been done differently to reduce the stigma experienced by the patient?

- Consider how you can integrate the voices of people with lived experiences into your work to help reduce stigma in your practice.

- Develop a plan for how you can advocate for anti-stigma policies in your workplace or community.

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2021). Australia’s health 2020: Mental health of young Australians. Australian Government. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia

Corrigan, P. W., Druss, B. G., & Perlick, D. A. (2014). The impact of mental illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 15(2), 37–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100614531398

Corrigan, P. W., Larson, J. E., & Rüsch, N. (2009). Self-stigma and the “why try” effect: Impact on life goals and evidence-based practices. World Psychiatry, 8(2), 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00218.x

Dockery, A. M., Kendall, G., Li, J., Mahendran, A., Ong, R., & Strazdins, L. (2015). Housing and children’s development and well-being: Evidence from Australian data. Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute. https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/253

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (US). (2014). Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioural Health Services (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 57). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207192/

Gee, G., Dudgeon, P., Schultz, C., Hart, A., Kelly, K.. (2014). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional wellbeing. In Dudgeon, P. Milroy, H. Walker, R. (Ed.), Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice (2nd ed.,pp. 55-68). Canberra: Australian Government Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

Henderson, C., Evans-Lacko, S., & Thornicroft, G. (2013). Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. American journal of public health, 103(5), 777–780. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301056

Jackson-Best, F., & Edwards, N. (2018). Stigma and intersectionality: A systematic review of systematic reviews across HIV/AIDS, mental illness, and physical disability. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 919. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5861-3

Jorm, A. F. (2020). Mental health literacy: Empowering the community to take action for better mental health. American Psychologist, 75(4), 613–622. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000405

National Mental Health Commission. (2024). Reducing stigma in mental health services. Australian Government. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au

Phelan, J. C., Link, B. G., & Dovidio, J. F. (2021). Stigma and prejudice: One animal or two? Social Science & Medicine, 113, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113081

Reavley, N. J., & Jorm, A. F. (2012). Public recognition of mental disorders and beliefs about treatment: Changes in Australia over 16 years. British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(5), 419–425. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.104208

Rodger, D. (2019). Diagnostic overshadowing: When mental health disorders obscure medical conditions. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(11–12), 2057–2065. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14768

Snowdon, D. A., Leggat, S. G., & Taylor, N. F. (2022). Does clinical supervision of healthcare professionals improve effectiveness of care and patient experience? A systematic review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 34(2), mzac030. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzac030

Tolosa-Merlos, D., Moreno-Poyato, A. R., González-Palau, F., Pérez-Toribio, A., Casanova-Garrigós, G., Delgado-Hito, P., & MiRTCIME.CAT Working Group (2023). Exploring the therapeutic relationship through the reflective practice of nurses in acute mental health units: A qualitative study. Journal of clinical nursing, 32(1-2), 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16223

World Health Organisation (WHO). (2023). Mental health action plan 2013–2030. World Health Organisation. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240036703