2 Integrating physical and mental health for holistic care

Learning Objectives

- Identify the interconnectedness between mental and physical health.

- Explain the impact of diagnostic overshadowing on patient care.

- Apply the illness-wellbeing continuum to assess overall patient well-being.

- Analyse the role of the Biopsychosocial model in holistic patient care.

- Develop comprehensive care strategies that integrate both mental and physical health assessments.

Introduction

To fully appreciate the need for integrating physical and mental health care, it is crucial that healthcare professionals first understand the definitions and distinctions between these two dimensions of health. As recapped from the first chapter of this text, both physical and mental health are vital components of overall well-being, each playing a critical role in determining patient outcomes. These aspects of health are intricately linked, influencing each other in ways that can either enhance or impede the quality of care and recovery.

Physical Health:

As discussed in the first chapter of this text, physical health refers to the proper functioning of the body and its systems, shaped by lifestyle choices such as diet, exercise, sleep, and daily habits. Good physical health is achieved when all bodily systems operate in harmony, allowing individuals to carry out daily activities without discomfort, pain, or illness. Contributing factors such as regular physical activity, a balanced diet, adequate rest, and avoidance of harmful substances (e.g., tobacco, alcohol) play a significant role in maintaining optimal physical health. In contrast, poor physical health can lead to chronic diseases like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity, which, in turn, can negatively influence mental health (Kandola & Osborn, 2022).

Mental Health:

Mental health involves emotional, psychological, and social well-being, influencing how individuals think, feel, and behave. It plays a central role in managing stress, coping with adversity, maintaining relationships, and making informed decisions. Mental health extends beyond the absence of mental illness, encompassing a person’s overall sense of well-being. Positive mental health enables individuals to reach their full potential, engage in productive work, and contribute to their communities (Das et al., 2020). Conversely, mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, and chronic stress can severely impair daily functioning and negatively impact physical health, leading to a reciprocal relationship between the two dimensions (Singh et al., 2022)

The Interconnection Between Physical and Mental Health:

The relationship between physical and mental health is bidirectional—physical conditions can affect mental well-being, and mental health issues can impact physical health (De Hert et al., 2011). Recognising this interdependence is crucial for healthcare professionals to deliver effective and comprehensive care.

- Mental Health Impacting Physical Health: Mental health conditions such as stress, anxiety, and depression can manifest as physical symptoms or exacerbate existing physical health problems. For example:

- Chronic stress has been linked to increased blood pressure and a higher risk of cardiovascular disease. The body’s response to stress, which involves the release of stress hormones such as cortisol, can contribute to inflammation, weight gain, and even immune system dysfunction (Vaccarino & Bremner, 2024).

- Depression is associated with poor physical health outcomes, including an increased risk of heart disease, diabetes, and stroke. Depression can also reduce a person’s motivation to engage in healthy behaviours like exercising, eating well, and adhering to medical treatments (Frank et al., 2023)

- Physical Health Impacting Mental Health: Chronic physical conditions can significantly affect a person’s mental health. For example:

- Cardiovascular diseases can lead to anxiety and depression, as the person may struggle with fear about their health, reduced physical capabilities, or concerns about future complications (Ski et al., 2024).

- Diabetes is often accompanied by feelings of stress and frustration due to the constant need for monitoring blood sugar levels, managing medications, and making lifestyle adjustments. These feelings can sometimes lead to the development of depression or anxiety (McInerney et al., 2022).

This intricate relationship is especially evident in people with serious mental illness (SMI). Individuals with conditions like schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder are at a significantly higher risk of developing physical health problems (De Hert, 2011). For example, they are more likely to experience cardiovascular disease, obesity, and diabetes, in part due to medication side effects, lifestyle factors, and barriers to healthcare access (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020;De Hert, 2011). Additionally, individuals with SMI tend to have a reduced life expectancy compared to the general population, largely due to preventable physical health conditions(Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2024).

Understanding the Link Through the Biopsychosocial Model:

The Biopsychosocial Model, first introduced by George Engel in 1977, offers a comprehensive approach to understanding the connection between physical and mental health (Bashmi et al., 2023; Steptoe & La Marca, 2022). This model suggests that health outcomes are influenced by a combination of biological, psychological, and social factors:

- Biological factors include genetics, physical health conditions, and biochemical imbalances.

- Psychological factors encompass emotional and cognitive processes, such as stress, mental health conditions, and coping mechanisms.

- Social factors involve relationships, cultural norms, socioeconomic status, and access to healthcare services.

By using the Biopsychosocial Model, healthcare professionals can assess and treat the person holistically, considering how their mental and physical health are interconnected and influenced by various external and internal factors.

Case Example: The Impact of Mental Health on Cardiovascular Disease

Consider a person with cardiovascular disease who also experiences untreated anxiety. Anxiety triggers a chronic stress response, which elevates cortisol and adrenaline levels, contributing to increased heart rate, higher blood pressure, and inflammation—all of which exacerbate the cardiovascular condition (Celano, Daunis & Lokko, 2016). In such cases, addressing the person’s anxiety is crucial for managing their physical health effectively (Ski et al., 2024). Ignoring the mental health aspect can lead to worse health outcomes and complicate treatment.

The Role of Integrated Care:

Recognising the connection between physical and mental health leads to the need for integrated care, where healthcare professionals from both disciplines work together to create comprehensive treatment plans. This approach ensures that the person with chronic physical conditions receive mental health support and that individuals with mental health disorders are regularly monitored for physical health issues (O’Farrell et al., 2022).

By acknowledging and addressing the interconnectedness of physical and mental health, healthcare professionals can ensure that patients receive care that enhances their overall well-being, rather than focusing on isolated symptoms or conditions. This integrated approach is particularly important for managing complex and chronic health issues, which often have both physical and mental dimensions.

Diagnostic Overshadowing in Healthcare:

Diagnostic overshadowing refers to the phenomenon where a healthcare provider attributes a patient’s physical symptoms to an existing mental health condition, thereby overlooking potential underlying physical health issues(Bueter, 2023). This bias often occurs in patients with serious mental illness (SMI), such as schizophrenia, anxiety, or depression, and can lead to missed diagnoses, delayed treatments, and ultimately, poorer health outcomes (Hallyburton, 2022).

Diagnostic overshadowing occurs when the complexity of a patient’s mental health condition obscures the clinician’s ability to see beyond the mental illness (Hallyburton, 2022). For example, a person with schizophrenia may report chest pain or other physical symptoms, but these complaints might be dismissed as anxiety-related or psychosomatic, rather than being investigated for potential heart disease or another serious physical condition. This can have serious, even life-threatening, consequences if physical health conditions are not properly identified and managed.

Patients with SMI are disproportionately affected by diagnostic overshadowing. Studies show that people with mental health conditions are at a significantly higher risk of developing physical illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and respiratory issues. However, they are often underdiagnosed or undertreated for these conditions because healthcare providers attribute their physical symptoms to their mental illness (Shefer et al., 2014).

Case Example:

Consequences of Diagnostic Overshadowing:

- Delayed Diagnosis: Critical physical health conditions may go undiagnosed for prolonged periods, worsening the patient’s condition and complicating treatment (Hallyburton, 2022)

- Suboptimal Care: Misattributing physical symptoms to mental illness can lead to incomplete assessments, with clinicians failing to explore the full range of potential diagnoses.

- Higher Mortality Rates: Diagnostic overshadowing contributes to the well-documented issue of premature mortality among individuals with SMI. People with SMI often die 10-20 years earlier than the general population, primarily due to untreated or poorly managed physical health conditions (Hallyburton, 2022).

- Patient Mistrust: Repeated experiences of diagnostic overshadowing can cause patients with SMI to lose trust in the healthcare system, making them less likely to seek care for physical symptoms in the future (Singh et al., 2023).

Strategies for Minimising Diagnostic Overshadowing:

Addressing diagnostic overshadowing requires systemic change in the way healthcare professionals approach patient care, particularly for individuals with SMI. The following strategies are essential for minimising the impact of this bias:

Implement Clinical Training and Awareness: A critical first step in combating diagnostic overshadowing is educating healthcare providers about the bias and its consequences. Training programs should:

-

- Focus on improving the ability of healthcare professionals to differentiate between physical and psychological symptoms (Hallyburton, 2022).

-

- Emphasise the importance of conducting thorough physical examinations and assessments for patients with mental health conditions, even when symptoms might initially seem to be linked to mental illness (Lazris et al., 2023).

-

- Raise awareness about the heightened risk of comorbid physical conditions among patients with SMI, particularly cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and respiratory illnesses (Hallyburton, 2022).

Develop Tools and Frameworks for Integrated Care: To ensure that both mental and physical health are given equal consideration in patient assessments, healthcare providers should use standardised tools and frameworks that prompt comprehensive evaluations. Examples include:

-

- Integrated Care Pathways: These pathways guide healthcare providers to systematically assess both physical and mental health when treating patients with SMI. For example, an integrated care pathway for patients with schizophrenia may include routine screenings for cardiovascular health, diabetes, and other common physical health conditions.

-

- Electronic Health Record (EHR) Alerts: EHR systems can be programmed to flag high-risk patients with SMI, prompting healthcare providers to check for physical health issues that may otherwise be overlooked. This can ensure that patients receive the necessary screenings and treatments for physical conditions in addition to mental health care (O’Farrell etal., 2022).

Encourage Multidisciplinary Collaboration: A multidisciplinary approach is critical for reducing diagnostic overshadowing. Collaboration between mental health professionals, primary care providers, and specialists ensures that all aspects of a patient’s health are considered. For example:

-

- Case Conferences: Regular case conferences between psychiatrists, general practitioners, and other healthcare providers allow for the discussion of complex cases and ensure that both mental and physical health concerns are addressed comprehensively.

- Shared Care Plans: Shared care plans, where mental health teams and physical health teams jointly manage a patient’s care, can ensure that physical health conditions are not overlooked.

Person-Centred Communication: Healthcare professionals should engage the person in open and empathetic communication, ensuring that their physical health concerns are taken seriously (Bueter, 2021). Strategies include:

-

- Active Listening: Allowing the person with SMI to fully express their physical health concerns without immediately attributing them to their mental health condition can reduce the risk of misdiagnosis.

- Person Empowerment: Encouraging the person to advocate for themselves by asking questions and requesting further evaluation if their concerns are dismissed can also help mitigate the effects of diagnostic overshadowing. Providing patients with tools to track their physical symptoms can further facilitate meaningful discussions with their healthcare providers.

Routine Physical Health Screenings for Patients with SMI: Implementing routine screenings for common physical health issues, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity, can help prevent diagnostic overshadowing. Healthcare professionals should ensure that the person with SMI receive regular check-ups and necessary tests, even when there are no immediate physical complaints. By proactively addressing the physical health of patients with mental illnesses, clinicians can reduce the likelihood of misattributing symptoms to their psychiatric condition (Lazris et al., 2023).

By recognising and actively working to counteract diagnostic overshadowing, healthcare professionals can provide more accurate, equitable, and comprehensive care for people with SMI. This approach ensures that both physical and mental health are given equal importance, leading to better outcomes and reducing the disparities faced by individuals with mental health conditions.

The Illness-Wellness Continuum and Its Application in Patient Care

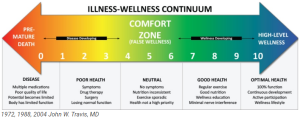

The Illness-Wellness Continuum (Figure 2.1), originally developed by Dr. John W. Travis in 1972 offers a comprehensive framework that views health as a dynamic spectrum, rather than a binary state of either “illness” or “health.” Rather than categorising individuals as simply ill or healthy, this model acknowledges that people can experience varying degrees of health and wellness, which can shift over time depending on numerous factors such as physical health, mental well-being, lifestyle choices, and resilience (Wickramarathne, 2020).

This continuum emphasises that health is not static but fluid, allowing individuals to move back and forth between different stages based on how they manage both their mental and physical health. The model shifts the focus away from merely treating illness to actively promoting wellness, encouraging healthcare providers to take a more holistic approach in patient care. The stages along the continuum include:

- Disease: Marked by worsening symptoms and multiple diagnoses requiring frequent medical intervention. At this stage, individuals often struggle with chronic conditions, and their mental health may also be negatively impacted by feelings of hopelessness or stress.

- Poor health: The early development of symptoms and diagnostic challenges may arise at this stage, potentially requiring medication or surgical intervention. Mental health issues like anxiety or stress often accompany this stage, compounding physical symptoms.

- Neutral: At this midpoint, individuals are not diagnosed with any specific health conditions but are also not actively pursuing wellness. Their physical and mental health are stable but vulnerable to decline without proactive health management.

- Good Health: Characterised by consistent physical activity, a balanced diet, and mental health awareness, individuals in this stage are managing both physical and mental health effectively. They might still face stress or minor health issues, but they have developed coping mechanisms to maintain balance.

- Optimal Health: This stage reflects high-level wellness, where individuals have achieved full functional capacity and are actively pursuing personal growth. They are physically, mentally, and emotionally balanced, significantly reducing the risk of illness through holistic lifestyle choices.

This model is particularly valuable when applied to patients managing chronic physical conditions, where mental health plays a significant role. For example, individuals with conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or chronic pain often experience fluctuations between states of good health and dysfunction, depending on how well they manage their physical and mental health (Baughman et al., 2016). Stress, anxiety, and depression are common co-occurring conditions in people with chronic illnesses, further emphasising the need for integrated care addressing both aspect (Celano et al., 2016; Ski et al., 2024).

Case Example: Applying the Continuum in Chronic Illness

Consider the case of Mr. James, a 55-year-old patient with chronic diabetes. Over the years, he has struggled to manage his blood sugar levels despite following treatment regimens and lifestyle changes. His condition is complicated by frequent hospital visits due to uncontrolled blood sugar, leading to feelings of frustration and helplessness. Initially, Mr. James was in the “neutral” range of the Illness-Wellness Continuum, where his physical health was stable, but he was not actively pursuing wellness. However, as his diabetes worsened and he began experiencing symptoms of depression—such as withdrawal from social activities, poor sleep, and feelings of worthlessness—he shifted toward the “dysfunction” stage.Despite regular medical care for his diabetes, Mr. James’s mental health had not been addressed, leading to a cycle where his emotional distress exacerbated his inability to manage his diabetes, pushing him further toward the “poor health” stage. This case highlights how chronic physical conditions can negatively impact mental health and how individuals can move along the Illness-Wellness Continuum as their overall health fluctuates.

Integrating Psychological Support in Chronic Care:

In Mr. James’s case, an integrative approach to care that considers both physical and mental health would be more effective in improving his overall well-being. The following strategies could be implemented:

- Psychological Interventions: Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) could be introduced alongside diabetes management to help Mr. James develop better coping mechanisms for managing his emotional response to his illness. Research has shown that CBT can significantly reduce symptoms of depression in individuals with chronic illnesses, leading to better physical and mental health outcomes (Trief et al., 2019).

- Lifestyle Modifications: A comprehensive care plan could include strategies to improve sleep hygiene, stress management, and social engagement—all of which can alleviate the emotional burden of living with diabetes and prevent further decline in physical health.

- Collaborative Care Model: Mental health professionals should work alongside endocrinologists, nutritionists, and other healthcare providers to ensure both physical and mental health needs are addressed. Regular mental health screenings during diabetes check-ups could help assess how Mr. James’s emotional well-being is influencing his diabetes management.

By applying the Illness-Wellness Continuum in Mr. James’s care, healthcare providers can recognize that his health is fluid and influenced by both mental and physical factors. Addressing both aspects holistically can prevent his mental distress from worsening, allowing him to move toward a state of “good health” or even “optimal health.” This approach ensures more effective treatment and improved quality of life.

Using the Illness-Wellness Continuum in clinical practice allows healthcare professionals to adopt a more dynamic and integrated view of health. By recognising the varying stages of wellness, particularly in a person with chronic conditions, they can provide tailored care that addresses both mental and physical well-being. This approach promotes empowerment of the person and encourages healthcare professionals to implement comprehensive care strategies that prevent illness and promote long-term wellness.

The Biopsychosocial Model in Practice

The Biopsychosocial Model is a holistic framework used in healthcare to address the full range of biological, psychological, and social factors influencing a patient’s health. Unlike traditional models that focus solely on biological symptoms, the Biopsychosocial Model emphasises that an individual’s health is shaped by the intricate interplay of their physical state, mental well-being, and social environment (Bashmi et al., 2023). This comprehensive approach ensures that healthcare providers consider all dimensions of a patient’s health when diagnosing and treating illnesses, particularly in complex cases involving both physical and mental health issues.

Key Components of the Biopsychosocial Model:

- Biological Factors: This includes the patient’s genetic makeup, physical health, and medical conditions. Biological interventions often focus on diagnosing and treating physical symptoms, managing medications, and addressing physiological imbalances, such as high blood pressure or blood sugar levels in diabetes.

- Psychological Factors: Mental and emotional well-being, including mood, personality traits, and coping mechanisms, are central to this component. Mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression, and stress are considered, as they can significantly affect physical health and treatment adherence.

- Social Factors: Social determinants of health, including the patient’s support system, socioeconomic status, and cultural background, are addressed. Social factors can either support or hinder recovery, with social isolation, poverty, or lack of access to healthcare exacerbating health conditions.

By integrating these three components, the Biopsychosocial Model moves beyond treating symptoms in isolation and provides a more person-centred approach to healthcare, encouraging professionals to explore how each dimension influences the other.

Application of the Biopsychosocial Model

The Biopsychosocial Model is especially effective in managing chronic physical conditions like cardiovascular diseases (CVD), chronic pain, and diabetes, which are often intertwined with mental health challenges. Addressing each component of the model leads to improved patient outcomes, particularly in cases where physical conditions exacerbate psychological distress or social factors contribute to health disparities (Steptoe & La Marca, 2022).

Cardiovascular Diseases (CVD):

Patients with CVD are at a higher risk of developing anxiety and depression due to the chronic nature of the condition and its impact on daily life. The Biopsychosocial Model allows healthcare providers to not only treat the biological aspects of heart disease—such as hypertension and cholesterol levels—but also to address psychological components like anxiety and stress management, as well as social issues like access to healthcare, support networks, and lifestyle factors (such as exercise and diet) (Steptoe & La Marca, 2022).

Nakao et al. (2021) highlight that integrating mental health interventions like cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) for patients with heart disease significantly reduced depression, improved quality of life, and enhanced adherence to medication and lifestyle changes. This evidence supports the need for a Biopsychosocial approach in treating CVD.

Chronic Pain:

Chronic pain conditions, such as fibromyalgia or arthritis, are often influenced by a patient’s psychological state and social circumstances. Pain can lead to depression, anxiety, and a diminished quality of life. The Biopsychosocial Model encourages interventions that go beyond medication to include psychological support (e.g., CBT to manage pain perception) and social interventions that address how a patient’s environment and support systems influence their pain management (Cheatle, 2016).

Biopsychosocial interventions can lead to significant improvements in both pain levels and psychological well-being for chronic pain patients compared to traditional biomedical treatments alone (Onwumere et al., 2022).

Diabetes:

Managing diabetes requires attention not only to blood sugar levels and insulin regulation but also to the psychological effects of living with a chronic condition, including stress, depression, and anxiety (Cohen, Edmondson & Kronish, 2015). Social factors, such as access to healthy food, healthcare services, and education about diabetes, also play a critical role in effective disease management. By using the Biopsychosocial Model, healthcare providers can develop a comprehensive care plan that incorporates patient education, psychological counselling, and social support to improve diabetes management outcomes.

People with diabetes who receive care that address both their psychological and social needs, alongside standard medical treatments, have better control of their blood sugar levels and reported improved mental health (Cohen, Edmondson & Kronish, 2015).

Case Example: A Patient with Cardiovascular Disease

Mr. Thompson is a 60-year-old patient with a history of cardiovascular disease (CVD), including hypertension and a recent myocardial infarction (heart attack). He has been prescribed medications to manage his cholesterol and blood pressure. However, in recent months, he has reported feelings of anxiety and depression related to his condition, including fear of another heart attack and feelings of social isolation since his physical activity has been restricted. He also struggles with adhering to his medication regimen due to forgetfulness and low motivation.

Applying the Biopsychosocial Model:

- Biological Component: The primary focus for Mr. Thompson is managing his cardiovascular condition. He is prescribed medications, including statins and beta-blockers, and is advised on dietary modifications to reduce his cholesterol levels. He is also scheduled for regular check-ups to monitor his heart health and prevent further complications.

- Psychological Component: Mr. Thompson’s anxiety and depression need to be addressed to improve his overall well-being and support his recovery. He is referred to a cognitive-behavioural therapist (CBT) to help manage his fear of having another heart attack and develop coping strategies to reduce his stress. His healthcare provider also offers relaxation techniques like mindfulness to reduce his anxiety levels and improve his mental resilience.

- Social Component: Social support is identified as a critical factor in Mr. Thompson’s recovery. Since he feels isolated, his healthcare team encourages him to join a local cardiac rehabilitation support group, where he can interact with others who have experienced similar heart conditions. Additionally, his family is involved in his care plan, helping to remind him to take his medications and encouraging him to stay engaged with his rehabilitation exercises.

Outcomes:

By addressing all aspects of Mr. Thompson’s health—his physical symptoms, psychological state, and social environment—the healthcare team creates a more effective and comprehensive care plan. Mr. Thompson’s mental health improves as his anxiety is reduced through therapy and relaxation techniques, leading to better medication adherence and a more proactive attitude toward managing his physical health. His involvement in the support group also reduces his sense of isolation, providing him with both emotional and practical encouragement to maintain his lifestyle changes.

Through the Biopsychosocial Model, healthcare professionals are able to provide a holistic, patient-centred approach to Mr. Thompson’s care, resulting in improved health outcomes and a higher quality of life.

Mental Health Conditions that Affect Physical Health:

Mental health conditions like anxiety and depression are not only psychological challenges but also have profound effects on physical health. These conditions can exacerbate chronic physical illnesses, impair treatment adherence, and reduce overall quality of life. In this section, we will explore how these mental health conditions intersect with physical health and the importance of integrating mental health care into the management of chronic diseases.

Anxiety

Anxiety disorders are among the most common mental health conditions, characterised by excessive worry, fear, and heightened physiological arousal (Celano et al., 2016). When anxiety becomes chronic, it can have detrimental effects on the body, contributing to the development or exacerbation of physical health issues. Anxiety triggers the body’s fight-or-flight response, causing the release of stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline. Over time, these hormones can lead to chronic stress, resulting in physical health complications (Celano et al., 2016).

Impact of Anxiety on Physical Health

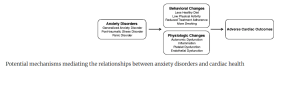

Chronic anxiety has been linked to several physical health conditions, particularly those related to the cardiovascular system. Figure 2.2 illustrates the proposed mechanism of connection between anxiety disorders and cardiac health:

Studies show that people with chronic anxiety are at an increased risk of developing high blood pressure (hypertension), heart palpitations, and digestive problems (Cohen, Edmondson, Kronish, 2015). The constant state of arousal caused by anxiety puts additional strain on the heart and other organs, which can worsen existing physical health conditions like cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Individuals with chronic anxiety may also experience:

Increased heart rate and palpitations: These symptoms mimic cardiac events, often causing additional stress and panic, which further aggravates cardiovascular conditions (Celano et al., 2016).

- Gastrointestinal issues: Anxiety has been linked to disorders like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and other digestive issues, which can complicate treatment and care for patients with physical health conditions (Hu et al., 2021)

Case Example: Anxiety and Hypertension

Mrs. Williams, a 55-year-old woman, has been living with hypertension for several years. Recently, she has been experiencing chronic anxiety due to work stress and financial difficulties. Her anxiety manifests physically with heart palpitations, tension headaches, and gastrointestinal discomfort. Despite being on medication for her hypertension, Mrs. Williams’ blood pressure remains elevated, and she is now at an increased risk of a cardiac event.

Her healthcare provider recognises that her untreated anxiety is exacerbating her hypertension. Mrs. Williams is referred to a cognitive-behavioural therapist (CBT) to help her manage her anxiety. She is also encouraged to adopt stress-reduction techniques, such as mindfulness meditation and deep breathing exercises, to lower her stress levels. In parallel, her antihypertensive medication is reviewed and adjusted.

Through this integrated approach, addressing both her anxiety and hypertension, Mrs. Williams’ blood pressure stabilises, and her overall well-being improves, reducing her risk of serious cardiac events.

Depression

Depression is another mental health condition with significant physical health implications. It is associated with chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and obesity (Mikkelsen & O’Toole, 2023). Depression not only reduces an individual’s ability to manage their physical health but also affects treatment adherence and self-care behaviours. Individuals with depression are less likely to engage in healthy behaviours like regular exercise, proper nutrition, and taking medications as prescribed.

Impact of Depression on Physical Health

Depression can lead to various physiological changes that negatively affect physical health (Mikkelsen & O’Toole, 2023), including:

- Chronic inflammation: Depression has been linked to increased inflammatory responses in the body, which are risk factors for chronic diseases like diabetes, CVD, and autoimmune disorders.

- Metabolic changes: Depression can alter the body’s metabolism, increasing the risk of developing insulin resistance and, consequently, type 2 diabetes.

- Reduced adherence to medical treatment: Individuals with depression are often less motivated to adhere to treatment plans, increasing their risk for complications in chronic conditions.

Case Example: Depression in a Patient with Diabetes

Mr. Johnson is a 60-year-old man diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. He has recently been struggling with clinical depression following the loss of his spouse. Due to his depression, Mr. Johnson has stopped attending his regular diabetes check-ups and has become inconsistent with his blood sugar monitoring and medication regimen. His diet has also deteriorated, leading to frequent episodes of hyperglycaemia (high blood sugar levels).

Mr. Johnson’s healthcare provider recognises that his depression is undermining his ability to manage his diabetes. He is referred to a psychotherapist to address his depression and is enrolled in a diabetes self-management support group. His healthcare team also works closely with him to set small, achievable health goals to regain control over his diabetes.

As Mr. Johnson begins to receive integrated care that addresses both his mental health and diabetes, his adherence to medication improves, his blood sugar levels stabilise, and his overall quality of life increases. Through this holistic approach, Mr. Johnson’s physical and mental health are both supported, leading to better long-term outcomes.

In summary, anxiety and depression are not isolated mental health conditions; they deeply affect physical health and complicate the management of chronic illnesses like hypertension, CVD, and diabetes (Silverman, Herzog & Silverman, 2019). Healthcare providers must recognise these connections and adopt an integrated approach that addresses both mental and physical health to optimise patient outcomes. By incorporating mental health support into treatment plans for chronic physical conditions, patients can experience better management of their overall health and improved quality of life.

The Role of Integrated Care in Reducing Premature Mortality in People with Mental Illness

Premature Mortality in People with Mental Illness

Individuals with serious mental illness (SMI) are disproportionately affected by premature mortality, largely due to comorbid physical health conditions such as cardiovascular disease, cancers, diabetes, and respiratory illnesses (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2024). People with SMI die earlier than the general population, with most deaths linked to preventable physical conditions rather than mental health issues alone ( Lawrence et al., 2016; Sara et al., 2021), . Factors contributing to these higher mortality rates include lifestyle factors, such as poor diet, lack of exercise, and smoking, but also the lack of access to timely and adequate healthcare for both physical and mental conditions.

Moreover, untreated mental health conditions exacerbate physical health issues. For example, chronic depression or schizophrenia can lead to poor treatment adherence, complicating the management of physical health problems like diabetes or hypertension. Individuals with SMI are also less likely to receive routine preventive care, such as cancer screenings, vaccinations, or health check-ups, leading to delayed diagnoses and treatment of physical conditions.

The Importance of Integrated Care

Integrated care, which treats both mental and physical health simultaneously, is crucial for reducing premature mortality in individuals with mental illness (Goodwin & Amelung, 2017). This holistic approach ensures that healthcare professionals consider the full range of a patient’s health needs, addressing mental health conditions alongside physical ailments, and vice versa. By integrating care, healthcare providers can help reduce the risk of preventable diseases, encourage better treatment adherence, and ultimately improve life expectancy and quality of life for individuals with SMI.

Research indicates that integrated care models can substantially reduce the mortality gap for people with SMI.. Interventions that combine psychological support with medical management lead to better overall health outcomes, including improved control of chronic physical diseases, reduced hospitalization rates, and a decreased risk of premature death. Integrated care teams consisting of mental health professionals, primary care physicians, and specialists can create comprehensive, person-centred treatment plans that address all aspects of a patient’s well-being.

Case Example: A Patient with Schizophrenia and Diabetes

Consider the case of John, a 52-year-old man with schizophrenia who has recently been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. John experiences delusions and has difficulty managing his diabetes, often forgetting to take his medication and struggling to adhere to a recommended diet and exercise plan. As a result, his blood sugar levels remain uncontrolled, increasing his risk of cardiovascular complications.

An integrated care team consisting of a psychiatrist, a primary care physician, and a diabetes nurse educator collaborates to create a holistic treatment plan for John. The psychiatrist helps stabilise symptoms of schizophrenia with antipsychotic medication and provides counseling to address his mental health needs. The diabetes nurse educates John on how to manage diabetes, while the primary care physician monitors his physical health, adjusting his medication regimen as needed.

Through regular check-ups and continuous coordination between the mental and physical health teams, John begins to better manage his diabetes, leading to improved blood sugar control. His mental health also stabilises, allowing him to engage more effectively in his treatment plan. Over time, John’s risk of cardiovascular complications decreases, and his overall quality of life improves, demonstrating the effectiveness of integrated care in reducing the risk of premature mortality for individuals with comorbid physical and mental health conditions.

By addressing the complex interaction between mental and physical health, integrated care models not only improve treatment outcomes but also enhance patient engagement, reduce the stigma surrounding mental health, and contribute to healthier, longer lives for individuals with SMI.

Practical Strategies for Healthcare Providers

Screening for Both Mental and Physical Health

One of the most effective strategies to improve patient outcomes in integrated care is the development of comprehensive screening guidelines that assess both mental and physical health conditions during routine patient visits (González-Ortiz et al., 2018; Goodwin & Amelung, 2017). As discussed earlier in this Chapter, individuals with chronic physical health issues, such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease, are at increased risk for mental health conditions, including anxiety and depression. Conversely, patients with serious mental illness (SMI) are often at heightened risk for physical health conditions, like metabolic syndrome or heart disease, making it critical that healthcare providers screen for both types of conditions during assessments. A comprehensive screening protocol could include:

- Physical Health Screening: Regular checks for common chronic conditions such as cancers, hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. This includes monitoring key indicators like blood pressure, cholesterol, BMI and glucose levels (Lamontagne-Godwin et al., 2018).

- Mental Health Screening: Routine comprehensive mental health assessments which incorporates the use of psychometric mental health assessment tools such as the Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale or Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to identify symptoms of anxiety, depression, or other mental health disorders (Pranckeviciene et al., 2022).

Integrating mental health screenings into regular health check-ups ensures that mental health issues are detected early, reducing the likelihood that these conditions will be overlooked or dismissed as secondary to physical ailments. Early identification and intervention are critical in preventing the exacerbation of both mental and physical health conditions.

Collaborative Care Models

Collaborative care models offer a structured approach to integrating mental health care into primary care settings. These models bring together primary care physicians, mental health professionals, and specialists in a coordinated effort to manage a patient’s full range of health needs (González-Ortiz et al., 2018; . Collaborative care typically involves:

- Co-location of Services: Mental health professionals, such as psychologists or psychiatrists, work within the same facility as primary care providers, making it easier for patients to access mental health services as part of their routine care.

- Shared Care Plans: Healthcare teams develop a unified care plan that addresses both physical and mental health issues. This plan is regularly reviewed and adjusted based on the patient’s progress, ensuring that all aspects of the patient’s health are managed holistically.

- Regular Communication: A collaborative care model ensures continuous communication between mental health and primary care providers, allowing for the timely sharing of information and coordinated adjustments to treatment strategies.

Collaborative care models are particularly effective for patients with comorbid conditions, such as diabetes and depression, where close monitoring of both mental and physical health is essential for improving outcomes (Atlantis, Fahey & Foster, 2014). By integrating mental health professionals into the primary care setting, patients receive more comprehensive and consistent care, ultimately reducing the risk of diagnostic overshadowing and improving overall health outcomes.

Patient Education and Empowerment

Patient education plays a pivotal role in promoting the connection between mental and physical health and encouraging self-management strategies(Dineen-Griffin et al., 2019; Franquez, de Souza & de Cássia Bergamaschi, 2023; González-Ortiz et al., 2018). When patients understand how mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression, can impact their physical well-being—and vice versa—they are more likely to take an active role in their own health management.

Strategies for patient education and empowerment include:

- Health Literacy Programs: Implementing educational programs that help patients understand the link between mental and physical health. These programs should cover topics such as the impact of stress on physical health, the importance of mental health screening, and how managing mental health can improve physical health outcomes.

- Self-Management Tools: Providing patients with resources, such as mobile apps, journals, or online platforms, that allow them to track their symptoms, medication adherence, and lifestyle changes. Empowering patients to take ownership of their health data helps foster a sense of control over their treatment.

- Shared Decision-Making: Engaging patients in shared decision-making processes, where they collaborate with healthcare providers to choose treatment options that align with their values and preferences. This patient-centred approach increases treatment adherence and satisfaction.

For instance, a patient with diabetes and anxiety might benefit from learning relaxation or stress reduction techniques to manage their anxiety, which can, in turn, help regulate their blood sugar levels (Robin et al., 2009) Empowering patients to understand the bi-directional relationship between mental and physical health motivates them to adopt healthier behaviours and adhere to treatment plans.

By implementing these practical strategies—comprehensive screening, collaborative care models, and patient education—healthcare providers can improve the integration of mental and physical healthcare, ultimately leading to better patient outcomes and a more holistic approach to care.

Summary

Integrating mental and physical health care is critical for improving patient outcomes, reducing premature mortality, and promoting holistic well-being. By recognising that mental and physical health are deeply interconnected, healthcare professionals can provide more effective, comprehensive care to patients, particularly those with chronic physical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, cancers, diabetes, or chronic pain, who are also at risk for mental health issues like anxiety and depression.

The failure to address both aspects of health can lead to diagnostic overshadowing, untreated conditions, and poorer patient outcomes, especially for those with serious mental illness (SMI). Integrated care ensures that both physical and mental health are considered equally, offering patients a better chance at recovery and a higher quality of life.

Healthcare professionals are encouraged to apply frameworks such as the Mental Health Continuum and the Biopsychosocial Model in practice. These models provide valuable tools for assessing the full spectrum of a patient’s health, acknowledging the fluid nature of mental well-being, and addressing biological, psychological, and social factors that affect health. By doing so, providers can offer personalised, patient-centred care that addresses the complexities of coexisting mental and physical conditions, ultimately improving long-term health outcomes for their patients.

Scenario Exercise:

Sarah is a 65-year-old woman with recently diagnosed with atrial fibrillation (AF). She experiences occasional palpitations and shortness of breath but is mostly asymptomatic. Her medical history includes hypertension and mild obesity. Sarah is anxious about her diagnosis, especially about the increased risk of stroke, and feels overwhelmed by the potential need for lifestyle changes. She lives alone in a rural area with limited access to specialized healthcare services. Her family is supportive but lives far away, making it difficult for them to assist with her day-to-day health management. Sarah is prescribed anticoagulants and beta-blockers to manage her condition but struggles to adhere to her medication regimen and lifestyle changes due to her anxiety and lack of nearby support.

Questions for Consideration:

- How can you, as a healthcare professional, address both Sarah’s physical health (atrial fibrillation and associated risks) and her psychological well-being to improve her treatment adherence and reduce anxiety?

- What social factors should be considered when developing a care plan, and how can these barriers be mitigated?

- How could you involve Sarah’s distant family and local community resources to strengthen her social support system and enhance her ability to manage her AF effectively?

- How can the Illness-Wellness Continuum be applied to Sarah’s situation to encourage behaviours that improve her overall well-being and long-term health outcomes?

References

Alvarez, A. S., Pagani, M., & Meucci, P. (2012). The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model in mental health: A research critique. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 91(13), S173-S180. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0b013e31823d54be

Atlantis, E., Fahey, P., & Foster, J. (2014). Collaborative care for comorbid depression and diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 4, e004706. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004706

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2020). National study of mental health and wellbeing. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-study-mental-health-and-wellbeing/latest-release

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2024). Physical health of people with mental illness. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health/physical-health-of-people-with-mental-illness

Bashmi, L., Cohn, A., Chan, S. T., Tobia, G., Gohar, Y., Herrera, N., Wen, R. Y., IsHak, W. W., & DeBonis, K. (2023). The biopsychosocial model of evaluation and treatment in psychiatry. In Atlas of Psychiatry (pp. 57-89). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15401-0_3

Baughman, K.R., Bonfine, N., Dugan, S.E. et al. (2016).Disease Burden Among Individuals with Severe Mental Illness in a Community Setting. Community Ment Health J 52, 424–432 . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9973-2

Bueter, A. (2021). Diagnostic overshadowing in psychiatric-somatic comorbidity: A case for structural testimonial injustice. Erkenntnis, 88, 1135-1155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-021-00396-8

Celano, C.M., Daunis, D.J., Lokko, H.N. et al.(2016). Anxiety Disorders and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr Psychiatry Rep 18, 101 . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-016-0739-5

Cheatle MD.(2016). Biopsychosocial approach to assessing and managing patients with chronic pain. Med Clin North Am.;100:43–53.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2015.08.007

Cohen, B. E., Edmondson, D., & Kronish, I. M. (2015). State of the art review: Depression, stress, anxiety, and cardiovascular disease. American Journal of Hypertension, 28(11), 1295-1302. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpv047

Daré, L.O., Bruand, PE., Gérard, D. et al. (2019) Co-morbidities of mental disorders and chronic physical diseases in developing and emerging countries: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 19, 304. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6623-6

Das, K. V., Jones-Harrell, C., Fan, Y., & Orlove, B. (2020). Understanding subjective well-being: Perspectives from psychology and public health. Public Health Reviews, 41, 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-020-00142-5

De Hert, M., Correll, C. U., Bobes, J., Cetkovich-Bakmas, M., Cohen, D. A. N., Asai, I., … & Leucht, S. (2011). Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders.. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World psychiatry, 10(1), 52.

Franquez, R. T., de Souza, I. M., & de Cássia Bergamaschi, C. (2023). Interventions for depression and anxiety among people with diabetes mellitus: Review of systematic reviews. PLOS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281376

Dineen-Griffin, S., Garcia-Cardenas, V., Williams, K., & Benrimoj, S. I. (2019). Helping patients help themselves: A systematic review of self-management support strategies in primary health care practice. PloS one, 14(8), e0220116. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220116

Frank PBatty GDPentti J, et al.(2023). Association Between Depression and Physical Conditions Requiring Hospitalization. JAMA Psychiatry. 80(7):690–699. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.0777

González-Ortiz, L. G., Calciolari, S., Goodwin, N., & Stein, V. (2018). The core dimensions of integrated care: A literature review to support the development of a comprehensive framework for implementing integrated care. International Journal of Integrated Care, 18(3), 10. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.4198

Goodwin, N., Stein, V., Amelung, V. (2017). What Is Integrated Care?. In: Amelung, V., Stein, V., Goodwin, N., Balicer, R., Nolte, E., Suter, E. (eds) Handbook Integrated Care. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56103-5_1

Hallyburton, A. (2022). Diagnostic overshadowing: An evolutionary concept analysis on the misattribution of physical symptoms to pre-existing psychological illnesses. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 31(6), 1360-1372. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.13034

Hu, Z., Li, M., & Yao, L. (2021). The level and prevalence of depression and anxiety among patients with different subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome: A network meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterology, 21, 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01593-5

Kandola, A. A., & Osborn, D. P. J. (2022). Physical activity as an intervention in severe mental illness. BJPsych Advances, 28(2), 112-121. https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2021.33

Lamontagne-Godwin, F., Burgess, C., Clement, S., Gasston-Hales, M., Greene, C., Manyande, A., Taylor, D., Walters, P., & Barley, E. (2018). Interventions to increase access to or uptake of physical health screening in people with severe mental illness: A realist review. BMJ Open, 8(2), e019412. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019412

Lawrence D, Hancock K and Kisely S (2013) The gap in life expectancy from preventable physical illness in psychiatric patients in Western Australia: retrospective analysis of population based registers– external site opens in new window’, British Medical Journal, 346:f2539, doi:10.1136/bmj.f2539.

Lazris, A., Roth, A., Haskell, H., & James, J. (2023). Diagnostic Overshadowing: When Cognitive Biases Can Harm Patients. American family physician, 108(3), 292–294.. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2023/0900/lown-right-care-diagnostic-overshadowing.html

McInerney, A. M., Lindekilde, N., Nouwen, A., Schmitz, N., & Deschênes, S. S. (2022). Diabetes distress, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms in people with type 2 diabetes: A network analysis approach to understanding comorbidity. Diabetes Care, 45(8), 1715-1723. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-2297

Mikkelsen, M. B., & O’Toole, M. S. (2023). A review of bodily dysfunction in depression: Empirical findings, theoretical perspectives, and implications for treatment.Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 33(3), 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000302

Murphy, B., Le Grande, M., & Jackson, A. (2024). Supporting mental health recovery in patients with heart disease: A commentary. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvae126

Nakao, M., Shirotsuki, K. & Sugaya, N.(2021). Cognitive–behavioral therapy for management of mental health and stress-related disorders: Recent advances in techniques and technologies. BioPsychoSocial Med 15, 16 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13030-021-00219-w

O’Farrell, A., McCombe, G., Broughan, J., Carroll, Á., Casey, M., Fawsitt, R., & Cullen, W. (2022). Measuring integrated care at the interface between primary care and secondary care: A scoping review. Journal of Integrated Care, 30(5), 37-56. https://doi.org/10.1108/JICA-11-2020-0073

Onwumere J, Stubbs B, Stirling M, Shiers D, Gaughran F, Rice ASC, C de C Williams A, Scott W. (2022).Pain management in people with severe mental illness: an agenda for progress. Pain. 1;163(9):1653-1660. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002633. Epub 2022 Mar 16. PMID: 35297819; PMCID: PMC9393797.

Pranckeviciene, A., Saudargiene, A., Gecaite-Stonciene, J., Liaugaudaite, V., Griskova-Bulanova, I., Simkute, D., Naginiene, R., Dainauskas, L. L., Ceidaite, G., & Burkauskas, J. (2022). Validation of the patient health questionnaire-9 and the generalized anxiety disorder-7 in Lithuanian student sample. PLOS ONE, 17(1), e0263027. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263027

Robin R. WhitebirdMary Jo KreitzerPatrick J. O’Connor.(2009). Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Diabetes. Diabetes Spectr 1, 226–230. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaspect.22.4.226

Sara, G., Chen, W., Large, M., Ramanuj, P., Curtis, J., McMillan, F., Mulder, C. L., Currow, D., & Burgess, P. (2021). Potentially preventable hospitalisations for physical health conditions in community mental health service users: A population-wide linkage study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 30, e22. https://doi.org/10.1017/S204579602100007X

Shefer, G., Henderson, C., Howard, L. M., Murray, J., & Thornicroft, G. (2014). Diagnostic overshadowing and other challenges involved in the diagnostic process of patients with mental illness who present in emergency departments with physical symptoms: A qualitative study. PLOS ONE, 9(11), e111682. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0111682

Ski, C. F., Taylor, R. S., McGuigan, K., Long, L., Lambert, J. D., Richards, S. H., & Thompson, D. R. (2024). Psychological interventions for depression and anxiety in patients with coronary heart disease, heart failure or atrial fibrillation: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvae113

Singh, B., Olds, T., Curtis, R., Dumuid, D., Virgara, R., Watson, A., Szeto, K., O’Connor, E., Ferguson, T., Eglitis, E., Miatke, A., Simpson, C. E., & Maher, C. (2022). Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety, and distress: An overview of systematic reviews. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 57(18), 1203-1215. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2021-104090

Singh, A., Amiola, A., Temple, P., et al. (2023). Diagnostic overshadowing & implications on treatment & rehabilitation of people with a genetic syndrome and co-existing psychiatric conditions: A case report of 22q11.2 duplication syndrome. Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Mental Health, 10, 443–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40737-023-00366-z

Silverman, A. L., Herzog, A. A., & Silverman, D. I. (2019). Hearts and minds: Stress, anxiety, and depression: Unsung risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Cardiology in Review, 27(4), 202-207. https://doi.org/10.1097/CRD.0000000000000228

Steptoe, A., & La Marca, R. (2022). The biopsychosocial perspective on cardiovascular disease. In A. Steptoe & R. La Marca (Eds.), Handbook of Cardiovascular Behavioral Medicine (pp. 81-97). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-85960-6_4

Vaccarino, V., Bremner, J.D. Stress and cardiovascular disease: an update. (2024).Nat Rev Cardiol 21, 603–616 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-024-01024-y

Wickramarathne, V. C., Phuoc, J. C., Rasmi, A., & Phuoc, C. (2020). A review of wellness dimension models: For the advancement of the society. European Journal of Social Sciences Studies. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3841435