1 Mental Health in Australia

Learning Objectives

- Define key mental health terms and concepts used in practice.

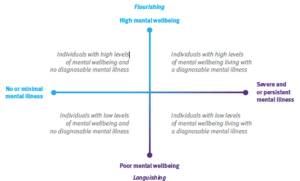

- Differentiate between mental health and mental illness using the Mental Health Continuum framework.

- Discuss the influence of biological, psychological, social, and cultural factors on mental health.

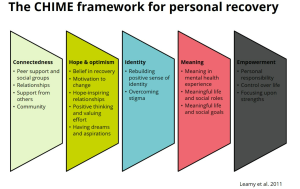

- Explain the recovery-oriented approach and its application in mental health care.

- Identify common barriers to accessing mental health services.

Introduction

Mental health is a core component of overall well-being, integral at every stage of life, from childhood through adulthood. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) highlights that nearly half of Australians aged 16 to 85 will experience a mental health condition at some point in their lives (AIHW, 2021). Mental illness and substance use disorders contribute significantly to Australia’s disease burden, ranking fourth in terms of morbidity and mortality after cancer, cardiovascular conditions, and musculoskeletal disorders. Notably, suicide and self-harm remain leading causes of disease burden among young people aged 15-24 and adults aged 25-44 (AIHW, 2021a).

Healthcare professionals are uniquely positioned to promote mental well-being and provide holistic care that addresses both physical and emotional needs, regardless of their clinical setting. This chapter introduces essential mental health terms and concepts used in Australia. It aims to equip healthcare professionals with the foundational knowledge necessary to support individuals experiencing mental health challenges across diverse healthcare settings.

Key terms and concepts in mental healthcare:

The Dimensions of Health:

Health is often viewed as merely the absence of disease or specific medical conditions. However, it encompasses more than that. The World Health Organisation (WHO, 2022) defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” This holistic perspective recognises multiple dimensions of health, including physical, psychological, emotional, social, and cultural well-being.

Physical Health: This dimension is traditionally the most understood aspect of a person’s well-being. Individuals with severe mental illness (SMI) face higher risks of physical health comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, which contribute to shorter life expectancies compared to the general population (Sara et al., 2021; Mushtaq etal., 2014; Lawrence et al., 2013). Research indicates that chronic physical conditions can lead to mental health issues such as depression and anxiety, while good mental health promotes healthier lifestyles and better physical outcomes. Interventions like physical activity programs can improve both physical and mental health by reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety (NSW Health, 2022; Singh, Olds, & Curtis, 2023).

Mental Health: This dimension refers to emotional, psychological, and social and cultural well-being, influencing thoughts, feelings, and actions (COAG Health Council, 2017; Das et al., 2020). Mental well-being fluctuates, influenced by genetics, personality, and day-to-day experiences such as financial stress, employment challenges, relationship difficulties, and significant life events. Social determinants of health, including living and working conditions, also play a critical role in shaping mental well-being (Carbone, 2021). Understanding that mental well-being and mental health conditions are interconnected but distinct allows healthcare professionals to tailor support based on an individual’s needs (Iasiello, van Agteren, & Cochrane, 2020).

Dimensions of mental wellbeing:

Psychological Well-being: This aspect involves self-esteem, emotional resilience, life satisfaction, and the ability to manage stress effectively. Psychological well-being is crucial for overall health, influencing how individuals perceive and respond to life events (Mental Health Commission of Western Australia, 2022). Research shows that enhancing psychological well-being through therapeutic interventions, such as cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), can significantly improve mental health outcomes (Vance et al., 2024).

Emotional Well-being: This subset of psychological well-being focuses on managing, understanding, and expressing emotions constructively. It is essential for decision-making and coping with life’s challenges. Emotional regulation skills, such as mindfulness and emotion-focused coping, are critical in maintaining overall health and resilience (Atta et al., 2024;Murrup-Stewart & Truong, 2024)

Social Well-being: Social well-being encompasses the quality of an individual’s relationships and their sense of belonging within their community. It includes maintaining meaningful relationships and engaging in social activities. Strong social support networks and community engagement are protective factors that enhance mental and physical health (Gee et al., 2014,Fox,et al., 2022). For Indigenous communities, a holistic approach emphasising connections to land, culture, and ancestry is fundamental to health outcomes (Dudgeon et al., 2020).

Cultural and Spiritual Well-being: Cultural and spiritual well-being are fundamental aspects of a person’s identity, fostering a sense of belonging, purpose, and connection. These dimensions significantly influence values, beliefs, and practices, with a strong cultural identity and spiritual connection serving as protective factors. They help mitigate mental health challenges and enhance resilience by providing meaning and support during times of adversity (Murrup-Stewart & Truong, 2024).Healthcare professionals have a responsibility to recognise and address the cultural and spiritual needs of individuals in their care. An understanding and respecting of diverse traditions, beliefs, and practices, can help develop trust, improve engagement, and contribute to better health outcomes. This approach underscores the interconnectedness of cultural and spiritual dimensions with overall well-being, emphasising the importance of inclusive, person-centered care that acknowledges the unique needs of each individual (Gopalkrishnan, 2018; Das et al., 2020). Incorporating cultural and spiritual considerations into healthcare ensures a holistic approach, addressing the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects of well-being.

The Mental Health Continuum Model

The Dual Continua Model explains that mental health and mental illness are distinct yet related dimensions (Iasiello, van Agteren, & Muir-Cochrane, 2020). On one continuum, mental health ranges from languishing (low well-being) to flourishing (high well-being). The other continuum measures mental illness severity, ranging from none to severe. This model highlights that individuals with mental illnesses can still experience high well-being if they have adequate support, while those without mental illness may still experience low well-being. Having positive or high levels of mental health can help prevent the development of certain mental illnesses and support an individual’s recovery journey, potentially reducing the severity, duration, and likelihood of relapse.

For instance, someone with depression might flourish if they have a strong support network, meaningful work, and engaging activities. Recognising this dynamic perspective allows healthcare professionals to focus not just on managing symptoms but also on enhancing overall well-being, promoting a more holistic and strengths-based approach to care (Mental Health Commission of Western Australia, 2022).

The Dual Continua Model of Mental Health and Mental Illness

Table: 1.1 Dual continua model application

Flourishing: Mark is a 28-year-old teacher who feels a deep sense of purpose in his work and enjoys strong connections with friends and family. He effectively manages daily stresses, like preparing lessons and handling classroom challenges, with resilience. Mark engages in activities he loves, such as hiking and volunteering, and experiences positive emotions regularly, contributing to his overall well-being.

Languishing: After a recent breakup, Mark starts feeling a ‘bit off’. While he isn’t experiencing full-blown depression, he goes through the motions of daily life, feeling disengaged and lacking motivation. He manages his responsibilities but struggles to find joy in activities he once loved. This state of languishing leaves him feeling somewhat stagnant, as he recognises he’s not thriving.

Minimal or No Mental Illness: In contrast, Mark’s friend Lisa, a 27-year-old nurse, generally experiences minimal or no mental illness. Despite the demands of her job and family responsibilities, she maintains a positive outlook and effective coping strategies. Lisa regularly practices self-care, including exercise and mindfulness, allowing her to manage stress and enjoy her life without significant mental health issues.

Severe or Persistent Mental Illness: Mark’s situation worsens over time. He begins to experience severe anxiety and persistent feelings of hopelessness that significantly interfere with his daily life. Simple tasks, like going to work or socialising, become overwhelming. After recognising that his symptoms are debilitating, he seeks help and is diagnosed with generalised anxiety disorder. With therapy and medication, Mark starts to learn how to manage his severe mental health challenges, aiming to regain stability.

This example illustrates the full range of experiences in the Dual Continua Model. Mark transitions from flourishing to languishing, and ultimately to experiencing severe and persistent mental illness, while Lisa represents an individual who maintains minimal or no mental illness. Together, they demonstrate how mental health can vary widely and change over time.

Mental illness

Mental illness is defined as a “clinically diagnosable disorder that significantly disrupts an individual’s cognitive, emotional, or social functioning” (COAG Health Council, 2017). However, people can still experience substantial impairments in their well-being even if they do not meet the full criteria for a mental illness diagnosis (Slade et al., 2009). In Australia, healthcare professionals, particularly psychiatrists, use standardised tools like the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) or the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11) to accurately diagnose mental health conditions (American Psychiatric Association, 2022; World Health Organisation, 2019).

Various terms are used to refer to “mental illness,” reflecting efforts to maintain clinical precision while reducing stigma and promoting a holistic approach to mental health care (Haslan & Baes, 2024). Terms like “severe and persistent mental illness,” “mental health condition,” “serious mental illness,” and “mental health problem” are commonly used interchangeably. It is important for professionals to differentiate between “mental health problems” and “mental illnesses.” While mental health problems may impact a person’s daily functioning, they are typically less severe and often arise due to temporary stressors. However, if left unaddressed, these issues can escalate into more severe mental health conditions.

Mental health disorders are typically characterised by three main components which are influenced by the biological, psychological, and social factors.:

- Deviation from Norms: This refers to behaviours that deviate from cultural or societal norms, such as unusual or socially inappropriate actions.

- Distress: This involves significant psychological and physical suffering that interferes with daily life. For instance, after the loss of a loved one, someone may experience emotional pain that makes it difficult to complete everyday tasks

- Dysfunction: This refers to disturbances in thinking, emotional regulation, or behaviour. For example, someone might experience persistent feelings of sadness or an inability to enjoy activities they once found pleasurable

Spectrum and Types of Mental Health Disorders

Mental health disorders encompass a wide range of conditions with varying severity and duration, including mood disorders, anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders, and substance use disorders (Sane Australia, 2024). According to recent studies, the most common mental health disorders diagnosed in Australian communities are mood disorders, which significantly affect emotional and cognitive functioning, leading to impaired social interactions (Dickins et al., 2019). These conditions often have significant impacts not only on individuals but also on their families and the broader society. For instance, mental illnesses are associated with economic challenges such as unemployment, reduced productivity, and increased risk of homelessness (Kirkbride et al., 2024). Moreover, stigma and discrimination exacerbate social isolation and prevent individuals from seeking timely care, further complicating treatment and recovery.

Diagnostic Process

The diagnostic process for mental illnesses involves comprehensive assessments conducted by a psychiatrist or qualified mental health professionals. This typically includes detailed interviews with the individual, as well as consultations with close family members or carers who are familiar with the person’s daily life and behaviour (Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 2023). Collecting thorough accounts of the person’s emotional state, behaviours, and the duration and intensity of symptoms is crucial for an accurate diagnosis.

While diagnostic labels offer clarity and guide effective treatment plans, they can also have drawbacks. On the positive side, these labels help align symptoms with established criteria, enabling access to targeted treatment and validating a patient’s experiences. However, they can also lead to stigma and social isolation, as individuals may feel reduced to their diagnosis rather than being viewed holistically (Mickelberg, 2024). Stigma in mental healthcare often prevents individuals from seeking or continuing treatment. Therefore, healthcare professionals must balance the need for diagnostic clarity with the application of person-centred and recovery-oriented approaches to minimise stigma and emphasise the individual’s unique experiences and strengths (Mickelberg, 2024).

Causes of Mental Illness

Mental illness results from a complex interaction of many factors that include genetic, biological, environmental and psychological factors. Understanding these elements is vital for healthcare professionals in supporting individuals and addressing underlying causes effectively (Australian Government Department of Health, 2023).

Genetic and Biological Factors:

Genetic predisposition is a significant factor in the development of mental illnesses. Studies show that individuals with a family history of conditions like depression, anxiety, or schizophrenia have a higher likelihood of developing these disorders themselves (Chen et al., 2022; Tao et al., 2024). Biological factors, such as neurotransmitter imbalances (e.g., serotonin and dopamine), also play a critical role (Ghallab & Elassal, 2024). These imbalances can affect mood regulation and cognitive function, contributing to conditions like depression and bipolar disorder. Watch the video below for a deeper understanding of the biology of mental illness.

- Environmental Stressors: Environmental factors, including trauma, chronic stress, and adverse life events, can interact with biological vulnerabilities, leading to or exacerbating mental health conditions (Kirkbride et al., 2024). For example, experiences like childhood abuse, domestic violence, or significant losses (e.g., death of a loved one) increase the risk of developing disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression. Chronic stressors, such as poverty, financial instability, and housing insecurity, further increase this risk, highlighting the need for a holistic approach to treatment that addresses both mental health and social determinants of health.

- Psychological Factors: Psychological factors such as coping mechanisms, self-esteem, personality traits, and previous trauma also influence mental health. Individuals with resilient coping strategies and high self-esteem are often better equipped to handle stress and adversity. In contrast, a history of trauma, such as childhood abuse or neglect, increases the likelihood of developing mental health disorders later in life (Trotta, 2022). Psychological resilience-building is therefore a key intervention focus for healthcare professionals to mitigate these risks.

- Current Stressors: Acute stressors, including relationship breakdowns, unemployment, and debt, can trigger or worsen existing mental health conditions. Healthcare professionals need to be aware of these factors to provide appropriate and timely support (Arena et al., 2022). Watch the video below for a deeper understanding acute and chronic stress.

Misinformation about mental illness is widespread, often resulting in harmful stereotypes and stigma. Common myths include the belief that people with mental health conditions are dangerous or incapable of recovery. In reality, individuals with mental illnesses can lead fulfilling lives with proper support and treatment (Corrigan et al., 2014). Correcting these myths is crucial for healthcare professionals, who should aim to educate their patients and the public to reduce stigma and promote an understanding of mental health.

Table 1.2: Examples of common myths along with facts to dispel them

| Myth | Fact |

|---|---|

| Mental illness is rare. | Mental illness is quite common; approximately 1 in 5 Australians experiences a mental health condition each year. |

| People with mental illness are violent. | Most individuals with mental illness are not violent and are more likely to be victims of violence. |

| Mental illness is a sign of weakness. | Mental illness can affect anyone, regardless of their strength or character; it’s a medical condition, not a personal failure. |

| Children don’t experience mental illness. | Mental health conditions can begin in childhood, with many disorders surfacing during early developmental years. |

| You can just "snap out of it." | Mental illnesses are not something that can be overcome through willpower alone; they often require professional treatment and support. |

| Therapy is only for severe mental illness. | Therapy can be beneficial for anyone, regardless of the severity of their condition; it’s a valuable tool for managing stress and improving well-being. |

| Medication is the only solution. | While medication can be helpful for many, effective treatment often involves a combination of therapy, lifestyle changes, and support. |

| Once diagnosed, you’ll have a mental illness for life. | Many people can and do recover from mental health conditions, especially with early intervention and appropriate treatment. |

| Mental health issues are not real illnesses. | Mental illnesses are legitimate medical conditions that affect brain function, behaviour, and emotions. They can have biological, psychological, and environmental causes. |

Biomedical vs. Holistic Approaches

The traditional biomedical approach to mental health focuses on diagnosing and treating conditions based on biological and biochemical factors, often using established diagnostic tools like the DSM-5 and ICD-11. While this model has been instrumental in standardising care and providing clear diagnostic criteria, it faces several criticisms:

- Narrow Focus: The biomedical model can overlook the social and psychological aspects of mental illness, potentially leading to inadequate care (Deacon, 2013).

- Lack of Personalisation: Treatment protocols based solely on clinical guidelines may not adequately reflect an individual’s personal experiences, thereby disempowering patients and reducing their engagement in their recovery (Rocca & Anjum, 2020).

- Stigmatisation: Viewing mental illness primarily through a medical lens can unintentionally reinforce negative stereotypes and stigma (Corrigan et al., 2014).

Person-Centred and Strengths-Based Care

Healthcare professionals are encouraged to adopt person-centred (Hormazábal-Salgado et al., 2024) and strengths-based approaches (Caiels et al., 2024) to counteract the limitations of the biomedical model. This involves focusing on the individual’s strengths and promoting active participation in their care. By understanding the person’s unique needs and collaborating on treatment plans, healthcare workers can empower individuals to manage their mental health and build resilience. This approach aligns with the growing emphasis on recovery-oriented practice in mental healthcare, which prioritises autonomy and personal growth (Australian Government Department of Health, 2013).

Example: Person centred approach in practice:

Consider Sarah, a 28-year-old woman who has been feeling anxious and overwhelmed for months. During her assessment, the healthcare professional, Alex, initially relies on a series of standard clinical questions to identify symptoms of anxiety. However, Alex quickly realises that these questions alone do not capture the full picture of Sarah’s experiences.

Shifting to a person-centred approach, Alex asks Sarah to describe how her anxiety affects her daily life. Sarah explains that her anxiety is closely related to work, where she feels unsupported, and public speaking is a significant trigger. Through this conversation, Alex gains a more holistic understanding of Sarah’s anxiety, allowing for a more tailored treatment plan.

This approach empowers Sarah by valuing her personal experience, making her an active participant in her care. Together, they develop a personalised plan that addresses her work environment and builds her confidence in public speaking.

Practical Roles for Healthcare Workers in a Person-Centred Approach

Healthcare professionals adopting person-centred care act as:

- Listeners and Advocates: Validating patients’ experiences and advocating for their needs.

- Guides: Assisting individuals through their treatment journey, ensuring access to appropriate services and resources.

- Educators: Providing information that empowers the person to make informed decisions.

- Supporters and Collaborators: Partnering with individuals to develop and adjust care plans that suit their unique circumstances and goals.

- Connectors: Linking individuals with community resources, support groups, and other healthcare professionals to ensure a comprehensive support network.

By integrating these roles, healthcare professionals enhance their impact, fostering a collaborative and inclusive approach to mental healthcare that aligns with best practices and evidence-based guidelines (Pullman et al., 2022).

Recovery in Mental Health: A Framework for Healthcare Professionals

Recovery from mental health conditions is a holistic, person-centred approach that focuses on enabling individuals to live fulfilling, meaningful lives, even when symptoms persist. Unlike the traditional biomedical model that prioritises symptom elimination, recovery-oriented practice acknowledges that people can achieve personal growth, autonomy, and improved quality of life despite ongoing challenges (Australian Government Department of Health, 2013).

This section explores the principles, frameworks, and practical elements of recovery-oriented mental health care. By understanding these concepts, healthcare professionals can better support individuals in their journey to recovery.

Understanding Recovery in Mental Health

Recovery is not a linear process nor a cure. It is an ongoing journey that prioritises self-determination, empowerment, and the active involvement of the person in their care. Recovery is highly individual, meaning it looks different for everyone. It involves setting personal goals, building on strengths, and regaining a sense of control over one’s life (Australian Government Department of Health, 2013).

The principles of recovery-oriented practice are increasingly integrated into Australian healthcare standards. The National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards advocate for person-centred and recovery-oriented approaches in mental health services, ensuring that care aligns with patients’ values and lived experiences (ACSQHC, 2018).

Core Elements of Recovery-Oriented Practice

- Person-Centred Care

Recovery-oriented practice focuses on the person’s needs, goals, and preferences, rather than solely treating symptoms. Healthcare professionals must collaborate with individuals to create care plans that reflect their unique circumstances and aspirations, promoting their autonomy and engagement in the treatment process (Klevan et al., 2023). - Holistic Approach

Recovery is about the whole person, not just their mental health condition. A holistic approach considers physical health, relationships, and community involvement, recognising that these elements are interconnected and influence overall well-being. This approach encourages healthcare professionals to look beyond clinical treatment, integrating social and lifestyle factors into the care plan. - Empowerment and Self-Direction

Empowerment is central to recovery. Individuals are encouraged to actively participate in decision-making processes, giving them control over their lives and care. Healthcare professionals are partners, facilitating self-determination rather than dictating treatment paths. This collaborative partnership builds trust and promotes better health outcomes. - Supportive Relationships and Community Engagement

Recovery is not an isolated process; it involves building and maintaining supportive relationships. Healthcare professionals, peers, family, and friends all play a crucial role. Community involvement and access to resources and opportunities, such as employment and education, are also integral to promoting long-term recovery (Leamy et al., 2011). - Hope and Optimism

The concept of hope is essential in recovery. It involves believing in the possibility of improvement and better quality of life, even when symptoms persist. Healthcare professionals can foster hope by supporting personal growth and highlighting the individual’s progress, resilience, and strengths (Klevan et al., 2023).

Table 1.3: Comparison between Biomedical and Recovery Oriented Approaches

| Aspect | Biomedical approach | Recovery oriented approach |

|---|---|---|

| Definition of Recovery | Elimination or control of symptoms through medical intervention | Personal journey towards a fulfilling life, despite the presence of symptoms |

| Focus | Symptom reduction and disease management | Holistic well-being, including personal goals and quality of life |

| Role of Healthcare Providers | Primary decision-makers and authorities on treatment | Partners or facilitators supporting the individual’s journey |

| Role of the person | Passive recipient of treatment | Active participant in their own recovery process. They are an expert by lived experiences. |

| Goal | Restoration of pre-illness functioning | Empowerment and self-determined quality of life |

| Example | Prescribing medication to manage schizophrenia symptoms | Developing a wellness plan that includes vocational training and peer support for a person with schizophrenia |

Barriers to Recovery in Mental Health Care

Question: Can Individuals with Chronic Mental Health Conditions Experience Good Mental Health?

Answer: Yes, individuals with chronic mental health conditions can experience good mental health, a concept that can be understood more clearly through the mental health continuum. The continuum is a framework used to describe the range of mental health experiences, from mental fitness and healthy functioning at one end to severe symptoms or conditions at the other. This model helps illustrate that mental health is not static but fluctuates over time depending on various factors, including stress, environment, and coping mechanisms.

Even with a chronic mental health condition, an individual can have periods where they are closer to the well-being end of the continuum. During these times, they may effectively manage their symptoms, engage in daily activities, and maintain positive relationships. This state is often achieved through a combination of treatment, such as medication and therapy, alongside supportive social relationships, healthy lifestyle choices, and effective coping strategies.

It’s important to understand that having a chronic mental health condition does not stop the possibility of experiencing good mental health. Rather, with appropriate support and management strategies, individuals can move back and forth along the continuum, experiencing periods of good mental health even amidst challenges. The mental health continuum model emphasises the dynamic nature of mental health and the potential for recovery and resilience in the face of chronic conditions.

The CHIME Framework of Recovery:

A useful model that guides recovery-oriented practice is the CHIME Framework. Developed through a comprehensive literature review, it identifies five processes that support recovery (Leamy et al., 2011):

Figure 1.2:

- C – Connectedness: Emphasises the importance of supportive relationships with family, friends, peers, and the broader community.

- H – Hope and Optimism: Encourages maintaining hope as a driving force for recovery, even during setbacks.

- I – Identity: Involves developing a positive self-identity that is not defined by the mental health condition.

- M – Meaning: Stresses the need for a sense of purpose in life through work, education, volunteering, or other personal interests.

- E – Empowerment: Focuses on individuals taking control of their lives and participating actively in their care decisions.

By applying the CHIME Framework, healthcare professionals can structure their care plans to include these key elements, enhancing the recovery journey for individuals.

Example: Implementation of the The CHIME framework

Leconbridge is a community mental health rehabilitation service. Their consumers (mental health service users) stay in small units on the site for 3-6 months, usually after an inpatient stay for acute mental health concerns. The service focuses on restoring and establishing skills to support independent living in the community.

Connectedness: The service organises regular peer-support groups discussing recovery challenges and strategies. Service users are able to connect with each other over shared experiences as well as develop supportive relationships.

Hope & Optimism: The service employs multiple Peer Workers, or Lived Experience Practitioners, who are able to provide hope and optimism for the future through demonstrating ability to work, and live, with enduring or past experience of mental illness. They also partner with local services who are able to employ and support vocational skills of the service users.

Identity: The service has a strong focus on identity, with service users encouraged to reflect on their values, strengths, and roles that they hold in life and wish to be involved in.

Meaning: They also have meaningful roles within the service that contribute to the collective community, for example service users taking responsibility for the community garden and taking on roles in cooking shared community meals. Individual therapy plans are developed in collaboration with service users, including goals and therapeutic activity that is meaningful to the individual.

Empowerment: The service is committed to encouraging and supporting self-determination of their service users. This includes service users being involved in every step of discharge planning and having transparent and clear processes that service users are encouraged to provide feedback on.

Despite the emphasis on recovery-oriented practice, several barriers can hinder recovery. Healthcare professionals must be aware of these barriers to effectively support individuals:

- Stigma and Discrimination

Stigma continues to be a significant barrier, impacting individuals’ willingness to seek help and engage in treatment. In Australia, stigma is particularly problematic in rural and Indigenous communities, where anonymity is limited, and fear of judgment is high (Corrigan et al., 2014). Healthcare professionals can counter stigma by using respectful, person-first language and promoting mental health literacy within their communities (Mental Health Commission, 2022).

- Diagnostic Overshadowing

Diagnostic overshadowing occurs when healthcare professionals attribute physical symptoms to a mental health diagnosis, leading to misdiagnosis or delayed treatment of other health conditions (Lown & Manning, 2023). This is a significant issue in Australia, where people with mental health conditions are often overrepresented in chronic physical illness statistics. Professionals must conduct comprehensive assessments and avoid assumptions based solely on mental health diagnoses.

- Language and Cultural Barriers

Language influences how mental illness is perceived and discussed. In some cultures, the absence of specific mental health terminology can lead to misunderstandings or denial of mental health conditions (Grover et al., 2020). This is especially true for culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities in Australia, where language differences and cultural beliefs can create significant barriers to accessing care (Mental Health Commission, 2022). Healthcare professionals should use culturally appropriate communication strategies and engage interpreters when necessary to ensure effective care delivery.

Strategies for Promoting Recovery

To overcome barriers and enhance recovery, healthcare professionals should adopt specific strategies:

Promote Mental Health Literacy

Education about mental health is essential for reducing stigma and encouraging help-seeking behaviour. Healthcare professionals can work with community organisations and public health campaigns to spread accurate information and demystify mental illness (Corrigan, Druss & Perlick, 2014). Increased awareness and understanding lead to earlier interventions and better recovery outcomes.

Provide Trauma-Informed Care

Understanding that many individuals with mental health conditions may have experienced trauma is crucial. Trauma-informed care focuses on creating a safe and supportive environment that minimises re-traumatisation, respects autonomy, and builds trust. This approach supports recovery by acknowledging the impact of past experiences and integrating this understanding into care plans (Huo et al., 2023).

Implement Recovery-Oriented Training for Healthcare Professionals

Training healthcare professionals in recovery-oriented and culturally competent practices ensures that they are equipped to provide person-centred and inclusive care. Such training should cover the use of appropriate language, how to engage in reflective practice, and how to build effective, non-stigmatising therapeutic relationships (McPherson et al., 2021)

Biomedical approach Vs Recovery Model

Example of the Biomedical Approach: A person diagnosed with major depressive disorder is prescribed antidepressant medication and regularly monitored by a psychiatrist. The focus is on symptom management and achieving remission through medical interventions.

Example of the Recovery Model: A person living with bipolar disorder collaborates with a mental health care professional to set personal goals, such as securing employment and building a supportive social network. In addition to these goals, they learn self-management techniques to handle mood swings and take an active role in their recovery journey.

Conclusion

This chapter has provided a comprehensive overview of the key concepts, models, and approaches in mental health care within Australia, offering healthcare professionals valuable insights to enhance their practice. By understanding the distinctions between mental health, mental illness, and the application of frameworks like the Mental Health Continuum, professionals can deliver more accurate assessments and tailor their interventions effectively. Emphasising the interplay of biological, psychological, social, and cultural factors highlights the need for a holistic approach that considers the whole person, beyond symptoms alone.

The chapter also underscored the importance of recovery-oriented practices, which empower individuals to take an active role in their own mental health journey. By integrating frameworks like CHIME (Connectedness, Hope, Identity, Meaning, and Empowerment), healthcare providers can create supportive environments that promote personal growth and long-term well-being. Additionally, addressing barriers such as stigma, diagnostic overshadowing, and cultural differences is critical in delivering accessible, equitable, and effective mental health services.

Ultimately, the insights and strategies discussed in this chapter aim to equip healthcare professionals with the beginning knowledge and tools needed to support individuals holistically, ensuring a compassionate and inclusive mental health system that meets diverse needs.

Scenario: Sarah’s Journey Through Mental Health Recovery

Sarah is a 35-year-old woman who has been diagnosed with major depressive disorder. She was admitted to the hospital after a period of severe low mood, withdrawal from her family and friends, and lack of self-care. Sarah’s medical history includes hypothyroidism, which has been managed with medication for several years. She is married and has two children, but her relationship with her spouse has become strained due to her ongoing mental health challenges.

During her hospital stay, Sarah meets with a multidisciplinary team, including a psychiatrist, mental health nurse, social worker, and occupational therapist. The team is tasked with creating a comprehensive care plan to support Sarah’s recovery.

Questions:

- How might focusing solely on Sarah’s medication and biochemical imbalances limit her overall recovery process? What other aspects of her health and well-being might be overlooked?

- In what ways does the person-centred approach empower Sarah in her recovery journey? How does involving her in goal-setting affect her motivation and engagement in treatment?

- What are some strengths Sarah might possess that could support her recovery? How can the healthcare team build on these strengths to help her achieve her goals?

- The recovery model emphasises the individual’s journey toward meaningful life beyond just symptom reduction. How can the team incorporate Sarah’s desire to reconnect with her family and regain her sense of purpose into a holistic recovery plan?

- How do the person-centred approach and the strengths-based approach differ from the biomedical approach in terms of their focus on Sarah’s overall well-being? Which approach do you think would lead to a more sustainable recovery, and why?

References:

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Arena, A. F., Harris, M., Mobbs, S., Nicolopoulos, A., Harvey, S. B., & Deady, M. (2022). Exploring the lived experience of mental health and coping during unemployment. BMC Public Health, 22, 2451. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14858-3

Atta, M. H. R., El-Gueneidy, M. M., & Lachine, O. A. R. (2024). The influence of an emotion regulation intervention on challenges in emotion regulation and cognitive strategies in patients with depression. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01949-6

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2018). National safety and quality health service standards user guide for health services providing care for people with mental health issues. ACSQHC. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au

Australian Government Department of Health. (2013). A national framework for recovery-oriented mental health services: Guide for practitioners and providers. Retrieved from https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/04/a-national-framework-for-recovery-oriented-mental-health-services-guide-for-practitioners-and-providers.pdf

Australian Government. (2022). National survey of mental health-related stigma and discrimination. Behavioural Economics Team of the Australian Government, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. https://behaviouraleconomics.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/projects/stigma-survey-report.pdf

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2021). Mental health. AIHW. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/mental-health

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2021a). Deaths by Suicide among Young people. AIHW. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias

Caiels, J., Silarova, B., Milne, A. J., & Beadle-Brown, J. (2024). Strengths-based approaches—Perspectives from practitioners. The British Journal of Social Work, 54(1), 168-188. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcad186

Carbone, S. (2021). What works to promote mental wellbeing and prevent the onset of mental health conditions? Prevention United. Retrieved from https://www.mhc.wa.gov.au/media/3940/wa-mhc-literature-review-final.pdf

Chen, W., Zeng, Y., Suo, C., Yang, H., Chen, Y., Hou, C., Hu, Y., Ying, Z., Sun, Y., Qu, Y., Lu, D., Fang, F., Valdimarsdóttir, U. A., & Song, H. (2022). Genetic predispositions to psychiatric disorders and the risk of COVID-19. BMC Medicine, 20(1), 314. https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-022-02520-z

COAG (Council of Australian Governments) Health Council. (2017). The Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan. Department of Health, Canberra. Accessed 10 September, 2024.

Corrigan, P. W., Druss, B. G., & Perlick, D. A. (2014). The impact of mental illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 15(2), 37-70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100614531398

Das, K. V., Jones-Harrell, C., Fan, Y., Ramaswami, A., Orlove, B., & Botchwey, N. (2020). Understanding subjective well-being: Perspectives from psychology and public health. Public Health Reviews, 41, 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-020-00142-5

Deacon, B. J. (2013). The biomedical model of mental disorder: A critical analysis of its validity, utility, and effects on psychotherapy research. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(7). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.09.007

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. (2022). National survey of mental health-related stigma and discrimination. https://behaviouraleconomics.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/projects/stigma-survey-report.pdf

Department of Health. (2024). Mental health and wellbeing: A national framework. Australian Government. Retrieved from https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/mental-health-and-wellbeing-a-national-framework

Ferry-Danini, J. (2018). A new path for humanist medicine. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics, 39(1), 57–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11017-018-9433-4

Fox, K. E., Johnson, S. T., Berkman, L. F., Sianoja, M., Soh, Y., Kubzansky, L. D., & Kelly, E. L. (2022). Organisational- and group-level workplace interventions and their effect on multiple domains of worker well-being: A systematic review. Work & Stress, 36(1), 30-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2021.1969476

Ghallab, Y.K., & Elassal, O.S. (2024). Biochemical and neuropharmacology of psychiatric disorders. In W. Mohamed & F. Kobeissy (Eds.), Nutrition and Psychiatric Disorders (pp. 2). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-2681-3_2

Gee, G., Dudgeon, P., Schultz, C., Hart, A., & Kelly, K. (2014). Social and emotional wellbeing and mental health: An Aboriginal perspective. In P. Dudgeon, H. Milroy, & R. Walker (Eds.), Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice (2nd ed.). Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

Gopalkrishnan, N. (2018). Cultural diversity and mental health: Considerations for policy and practice. Frontiers in Public Health, 6(179). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00179

Grover, S., Shouan, A., & Sahoo, S. (2020). Influence of language in understanding mental health issues in a multicultural society. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(4), 345-351. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020902654

Haslam, N., & Baes, N. (2024). What should we call mental ill health? Historical shifts in the popularity of generic terms. PLOS Mental Health, 1(1), e0000032. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmen.0000032

Holmes, H., Darmanthe, N., Tee, K., & et al. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences—Household stressors and children’s mental health: A single-centre retrospective review. BMJ Paediatrics Open, 5, e001209. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2021-001209

Hormazábal-Salgado, R., Whitehead, D., Osman, A. D., & Hills, D. (2024). Person-centred decision-making in mental health: A scoping review. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 45(3), 294-310. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2023.2288181

Huo, Y., Couzner, L., Windsor, T., Laver, K., Dissanayaka, N. N., & Cations, M. (2023). Barriers and enablers for the implementation of trauma-informed care in healthcare settings: a systematic review. Implementation Science Communications, 4(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-023-00428-0

Iasiello, M., van Agteren, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2020). Mental health and/or mental illness: A scoping review of the evidence and implications of the dual-continua model of mental health. Evidence Base, (1). https://doi.org/10.21307/eb-2020-001

Kirkbride, J. B., Anglin, D. M., Colman, I., Dykxhoorn, J., Jones, P. B., Patalay, P., & Griffiths, S. L. (2024). The social determinants of mental health and disorder: Evidence, prevention, and recommendations. World Psychiatry, 23(1), 58-90. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21160

Klevan, T., Sommer, M., Borg, M., Karlsson, B., Sundet, R., & Kim, H. S. (2023). Toward an experience-based model of recovery and recovery-oriented practice in mental health and substance use care: An integration of the findings from a set of meta-syntheses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(16), 6607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20166607

Lawrence, D., Hancock, K. J., & Kisely, S. (2013). The gap in life expectancy from preventable physical illness in psychiatric patients in Western Australia: Retrospective analysis of population-based registers. BMJ, 346, f2539. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f2539

Leamy, M., Bird, V., Boutillier, C. L., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2011). Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(6), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733

Lown, B. A., & Manning, C. (2023). Diagnostic overshadowing: When cognitive biases can harm patients. American Family Physician, 108(3), 292-294. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2023/0900/lown-right-care-diagnostic-overshadowing.html

McPherson, P., Lloyd-Evans, B., Dalton-Locke, C., & Killaspy, H. (2021). A systematic review of the characteristics and efficacy of recovery training for mental health staff: Implications for supported accommodation services. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 624081. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.624081

Mental Health Commission. (2022). Engagement with culturally and linguistically diverse communities to support the development of the national stigma and discrimination reduction strategy. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/publications/stigma-strategy-cald-engagement-final-report-publication

Mental Health Commission of Western Australia. (n.d.). Western Australian mental well-being guide. Retrieved September 9, 2024, from https://www.mhc.wa.gov.au/media/4747/mental-wellbeing-guide.pdf

Minas, H. (2018). Mental health in multicultural Australia. In D. Moussaoui, D. Bhugra, & A. Ventriglio (Eds.), Mental health and illness worldwide: Mental illness in migration (pp. 1–30). Springer.

Mickelberg, A. J., Walker, B., Ecker, U. K. H., & Fay, N. (2024). Helpful or harmful? The effect of a diagnostic label and its later retraction on person impressions. Acta Psychologica, 248, Article 104420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104420

Murrup-Stewart, C., & Truong, M. (2024). Understanding culture and social and emotional wellbeing among young urban Aboriginal people. Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from https://aifs.gov.au/resources/short-articles/understanding-culture-and-social-and-emotional-wellbeing-among-young-urban

Mushtaq, R., Shoib, S., Shah, T., & Mushtaq, S. (2014). Relationship between loneliness, psychiatric disorders and physical health: A review on the psychological aspects of loneliness. Journal of Clinical Diagnostic Research, 8(9), WE01-WE04.

NSW Health. (2021). Physical health care for people living with mental health issues (GL2021_006). NSW Government. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au

Pullman, J., Santangelo, P., Molloy, L., & Campbell, S. (2022). Impact of strengths model training and supervision on the therapeutic practice of Australian mental health clinicians. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 31(5), 1234-1245. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.13079

Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. (2023). Clinical practice guidelines for the management of mental health disorders. Retrieved from https://www.ranzcp.org/files/resources/college_statements/clinical_practice_guidelines.aspx

Rocca, E., & Anjum, R. L. (2020). Complexity, reductionism, and the biomedical model. In R. L. Anjum, S. Copeland, & E. Rocca (Eds.), Rethinking causality, complexity, and evidence for the unique patient (pp. 89-106). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41239-5_5

Sara, G., Chen, W., Large, M., Ramanuj, P., Curtis, J., McMillan, F., … Burgess, P. (2021). Potentially preventable hospitalisations for physical health conditions in community mental health service users: A population-wide linkage study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 30, e22. https://doi.org/10.1017/S204579602100007X

Singh, B., Olds, T., Curtis, R., & et al. (2023). Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety, and distress: An overview of systematic reviews. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 57(1203-1209). https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2022-1065784

Tao, Y., Zhao, R., Yang, B., Han, J., & Li, Y. (2024). Dissecting the shared genetic landscape of anxiety, depression, and schizophrenia. Journal of Translational Medicine, 22, 373. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-024-05153-3

Trotta, A. (2022). Childhood trauma and mental health: Never too early to intervene. In M. Colizzi & M. Ruggeri (Eds.), Prevention in mental health: From risk management to early intervention (pp. 91–108). Springer Nature Switzerland AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97906-5_5

Vance, A., McGaw, J., O’Rorke, D., White, S., & Eades, S. (2024). Culture, health and wellbeing: Yarning with the Victorian Indigenous community: Indigenous yarning about culture and health. International Journal of Indigenous Health, 19(1). Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.32799/ijih.v19i1.41307

World Health Organisation. (2019). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th ed.). Retrieved from https://icd.who.int/

World Health Organisation. (2022). Constitution of the World Health Organisation. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/about/governance/constitution.