8.2 From Italia to Melbourne: A Culinary Journey of Italian Migration

Cristina M. Thompson

In the bustling streets of Melbourne, amongst the vibrant multicultural tapestry, lies a delicious tale of migration and culinary innovation. Today, Australia offers a delightful variety of cuisine from diverse cultural backgrounds. With food providing a lens into the narratives of cultures, Australia boasts a rich tapestry of culinary treasures from around the globe. But have you ever wondered how staples like pizza and pasta became everyday delights Down Under? Let’s take a closer look at Australia’s culinary journey, beyond the simple notion that it was shaped by migrant communities.

Think about it: imagine a time when you couldn’t easily find salami or mozzarella, and the idea of sipping a morning cappuccino on your way to work was unheard of. This essay delves into the captivating story of Italian migration and its impact on the vibrant food scene of Melbourne. Exploring how Italian cuisine has blended into Australian cooking, this study traces the obstacles faced by Italian migrants in the 1900s and examines how they made a lasting impact with their flavourful contributions. By employing a methodological approach grounded in both primary and secondary sources, I aim to unravel the fascinating interplay between migration, cultural exchange, and the evolution of gastronomy.

Prepare to uncover the delicious layers of Australia’s culinary heritage.

Cultural Transitions through Culinary Contraband

Italian migrants, yearning for a taste of home in Australia, began smuggling salami—a cherished culinary treasure—into the country, concealed within their belongings and in “tins of olive oil”.[1] For these migrants, salami symbolised not only sustenance but a tangible link to their cultural identity and heritage. Their efforts, however, did not escape the scrutiny of the Australian authorities, who commenced vigilant inspections of their luggage, detecting, and confiscating contraband salami. An Article published in the Daily News on 25 March 1955, “No Salami This Time” (see Figure 1), illustrates the importance of this single food commodity and provides valuable insights into the challenges and adaptations faced by Italian immigrants as they introduced their cuisine to Australia.

Today, a variety of cured meats and cheeses grace the shelves of supermarkets, delicatessens, and the local milk bar. They have integrated into our daily routines as essential components of our lunchtime ‘sangas’, pizza toppings, or convenient on-the-go snacks.

Charcuterie boards are a popular feature at parties and functions and can be purchased from markets or small businesses. Figure 2 depicts a small charcuterie board available to purchase or recreate for various occasions. By comparing figures 1 and 2, we can see the changing attitudes to salami as a commodity and how it significantly influenced Australian dietary habits, reflecting its widespread adoption and culinary versatility. However, this development does not appear to have been seamless.

Displacement and Discontent: Food at Bonegilla Migration Centre

For many Italian migrants, their life in Australia began at Bonegilla, a Migration Reception and Training centre located in Northern Victoria. Amid unfamiliar surroundings, Italian migrants found temporary refuge and support. Between 1947 and 1971, around 300,000 migrants, from over 50 nations, arrived on Australian shores, Italians being among them.[2]

At Bonegilla, meals were served based on military rations, featuring a menu dominated by mutton—a meat many migrants found unpalatable.[3] Richard Bosworth’s account illustrates the unappealing meals that migrants endured: “A cold mutton chop, covered with a sauce ‘absolutely unknown in Italy’ was no solace for an unemployed Italian”.[4] The bland food had stripped them of their identity and fed on their vulnerability instead of nourishing them. Bonegilla became a place of negative connotations in migrant memories. For the Italian diaspora, mealtime at Bongilla signified their displacement from their homeland. Alternatives such as private cooking were prohibited due to safety concerns.

The fascinating sagas of Bonegilla are brought to life through vivid oral histories and personal accounts. One fascinating account from Elis P in 1959 paints a bleak picture of the “awful” food provisions: “We had to queue up for our meals at the dining room. And the food was awful – overcooked pasta with a grey coloured sauce”.[5]

In addition to this, Nadia Postiglione’s publication “It Was Just Horrible”: The Food Experience of Immigrants in 1950s Australia’, delves deeper into these culinary afflictions, highlighting how critical food experiences were for post-war migrants.[6] Nadia’s analysis of migrant complaints revealed that Bonegilla exposed newly arrived migrants to experiences of food alienation and food dispossession, suggesting that these issues cast a negative light on the organisation of the migration experience.[7] Frustrations boiled over as Italian migrants voiced their grievances, leading to two notable riots. In 1952, a riot erupted among the Italian community, famously known as the ‘Spaghetti riot’.[8] Following this uprising, Italian cooks were appointed to the Italian blocks, receiving special supplies of fish, macaroni, spaghetti, and other staples essential to their culinary heritage.[9]

The culinary renaissance wasn’t limited to the Italians. Other cultural groups at Bonegilla saw similar improvements as migrant cooks from diverse backgrounds took charge of the kitchen, gradually transforming the quality of meals. This not only uplifted the spirits of the migrants but also showcased their resilience and determination to preserve their cultural identity even in the face of adversity.

Envisioning the mealtime scene at Bonegilla, as suggested in Figure 3, we can almost taste the evolution of the food. However, without knowing the date of the image, it is uncertain whether it depicts the bleak early days or the improved dining experiences that followed the culinary uprising.

This tale of Bonegilla is a testament to the power of food in shaping migrant experiences and the unyielding spirit of those who sought to make a new home without abandoning their heritage.

Cultural Enclaves and Integration Efforts: The Italian Culinary Influence in Australian Society

When Italians migrated to Australia, many arrived without formal English, turning this language barrier into a catalyst for creating tight-knit communities. They found solace among fellow Italians, sharing backgrounds, language and the comforting aroma of home-cooked meals. The majority of migrants trailed their relatives or friends who had previously migrated to Australia, pursuing not only job opportunities but also personal support.[10] Settling in neighbourhoods like Coburg, Fawkner, and Carlton—soon to be known as Little Italy—they found a sense of belonging.

Lygon Street began to thrive as Italian migrants began to establish small businesses, infusing the area with the rich flavours and traditions of their homeland. Delis and cafes emerged, offering imported Italian foods, and serving espresso – a staple of Italian culture. These establishments became social hubs where Italians could converse in their language, developing a sense of connection and solidarity. Soon, Lygon Street became a vibrant hub, buzzing with life. It was not just a culinary hotspot, but also a cultural and social centre where the Italians celebrated their heritage and forged new bonds in their adopted land.

While conducting research for this project, the memories of my own father became a useful ethnographic tool. Phillip Perroni, who migrated to Australia in 1959 and again in 1981 recalls, “I think Lygon Street became a catalyst for other Italian restaurants in Melbourne, I don’t remember going to any Italian restaurants as a boy here in Australia, food was always shared within the community.”[11]

Australians quickly embraced the Italian cuisine, discovering new flavours and cultural traditions that were woven into the Anglo-Australian food culture. The bustling energy and warmth of Lygon Street became symbolic of Australia’s multicultural identity, showcasing the enriching exchange between cultures and the vibrant tapestry of society. Lygon Street became a focal point, as Phillip Perroni shares: “I remember in 1982 Lygon Street closed off to celebrate the victory of Italy in the World Cup, there was food, drinks and festivities”.[12]

As historians, we bear an ethical and moral obligation as the gatekeepers of the past. In narrating the story of Italian migration and its impact on Melbourne’s food scene, we must be mindful of the diverse perspectives and experiences that shaped this journey. While celebrating the culinary contributions of Italian immigrants, we must also acknowledge the challenges they faced – from discrimination to language barriers – and the resilience they demonstrated in overcoming them. By presenting a nuanced and empathetic portrayal, we honour not just the flavours but also the human stories behind them.

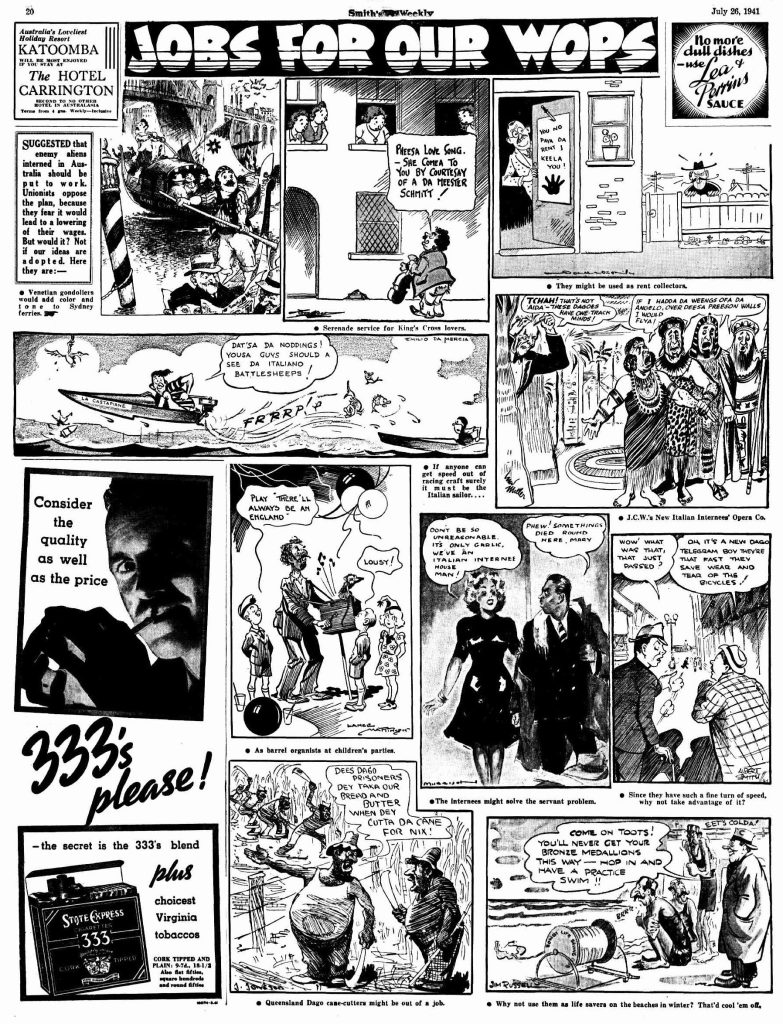

Throughout the 1950s and 1970s, a predominant portion of ‘white’ Anglo-Australians held onto objectives for a culturally and racially uniform society, encouraging what they perceived as the essential ‘Australian way of life’.[13] This mindset was often expressed through satirical cartoons (see Figure 4) and media that fuelled strong emotional reactions against perceived ‘threats,’ such as migration.[14] This led the Italian ethnic community to become determined to construct their own utopian community.

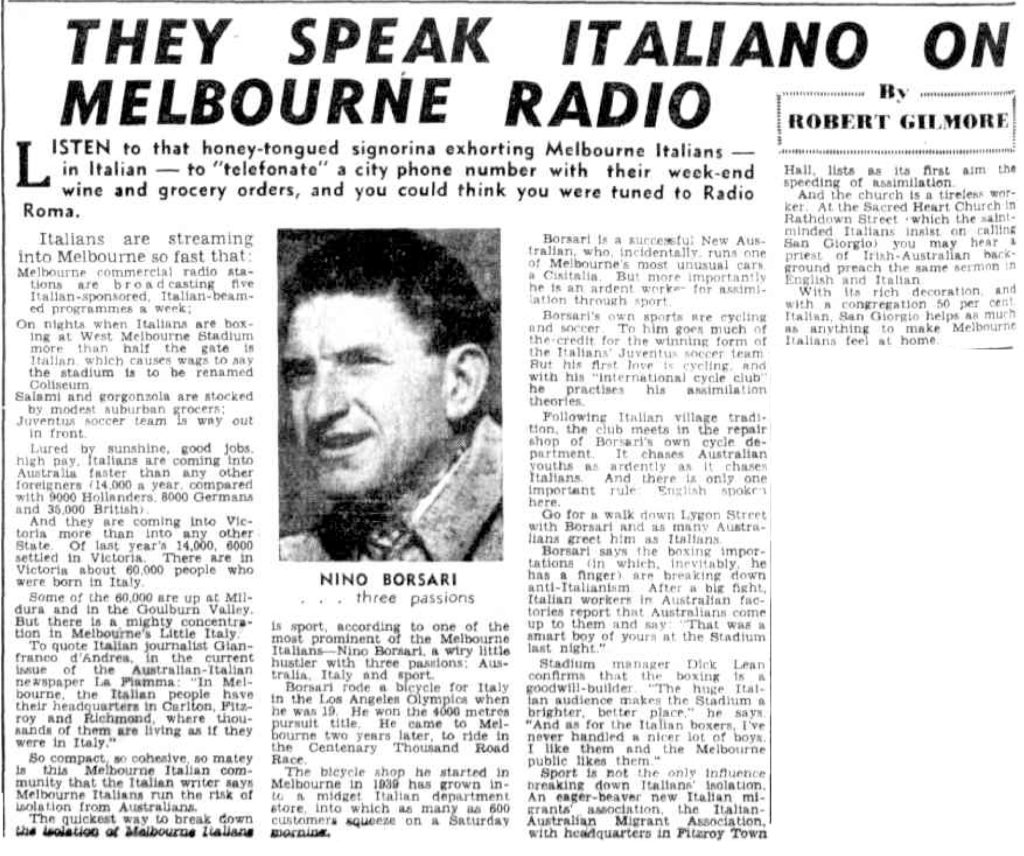

Drawing our attention to Figure 5, we can see how much Italians changed the landscape from 1954. As outlined in the newspaper article, Italian delicacies like salami and gorgonzola became staples in suburban grocery stores. The advancement of Italian immigrants in Melbourne’s Little Italy, especially in suburbs like Carlton, Fitzroy, and Richmond, created a close-knit and cohesive community. However, the newspaper article also voices concerns regarding potential isolation from mainstream Australian society. The assimilation of Italian migrants in Australia, exemplified by figures like Nino Borsari, was instrumental in shaping both their integration and Australia’s culinary landscape. Borsari’s efforts to promote sports and community events helped Italian immigrants bridge cultural divides and foster better relationships with Australians. This integration facilitated the gradual acceptance and incorporation of Italian foods into mainstream Australian cuisine. As Italian delicacies like salami and gorgonzola transitioned from exotic items to everyday staples, they reflected the successful blending of Italian culinary traditions into Australian food culture. This process highlights how Italian migration not only led to cultural assimilation but also significantly transformed Australia’s culinary landscape.

Pineapple on Pizza?

In the colourful tapestry of modern culinary culture, Italian cuisine reigns supreme, popping up in eateries, grocery stores, and cookbooks faster than you can say ‘mamma mia!’ Italian recipes continue to inspire even the most clueless chefs.

Today, Australians—both Italian and Anglo—are engaged in a lively debate over whether pineapple belongs on pizza. This contentious issue pits Italians against Australians in a flavourful clash that is as spirited as a ripe tomato and as cheesy as pizza itself. Whether you’re on Team Pineapple or staunchly opposed to tropical toppings, one thing is certain: the fusion of Italian zest and Aussie flair creates a flavour explosion that’s worth celebrating.

Melbourne provides a kaleidoscope of cultures; a delicious tale of migration and culinary innovation unfolds. Food, as a universal language, offers a unique window into the diverse narratives of cultures interlocking. Italian migrants, yearning for a taste of home in their new land, brought with them cherished culinary traditions and ingredients, even resorting to clever smuggling tactics to preserve their cultural identity. From humble beginnings, Italian delicacies like salami and mozzarella have become pantry staples across Australian households, symbolising not just nourishment but also a profound connection to heritage.

Picture this: a journey filled with obstacles, where Italian migrants, like those at the Bonegilla Migration Centre, faced displacement and a sense of being uprooted from their culinary heritage. But in the face of adversity, their resilience shone through as they fought to keep their cultural identity and culinary traditions alive. Now, shift your gaze to the bustling streets of Melbourne, especially the iconic Lygon Street: here, Italian migrants worked their magic, transforming the culinary landscape by bringing the flavours and traditions of their homeland to life. Suddenly, delis and cafes became more than just places to grab a quick coffee; they evolved into vibrant cultural hubs where language barriers faded away over plates of pasta and cups of espresso. Let’s not forget the delightful debate that ensued: pineapple on pizza! This playful argument between Italians and Australians perfectly captures the fusion of cultures and flavours, reminding us that food is not just about sustenance—it’s a source of joy and companionship.

In narrating the story of Italian migration and its impact on Australian cuisine, we must pay homage to the challenges faced by migrants while celebrating their resilience and cultural contributions. Through the lens of food, we gain a deeper understanding of the human stories behind the flavours that enrich our lives. So, whether you’re on Team Pineapple or a traditionalist, let’s raise a slice to the delightful blend of Italian zest and Australian creativity that defines our culinary landscape. Buon appetito!

Bibliography

Bonegilla Migrant Experience, Discover Bongellia [image], (n.d), https://discover.bonegilla.org.au/Suitcase-Trail/Food#, accessed 20 April 2024.

NOAUTHOR, ‘Food’, Discover Bonegilla [website] (n.d), https://discover.bonegilla.org.au/Suitcase-Trail/Food#, accessed 20 April 2024.

‘No Salami This Time.’ The Daily News [image]. March 25, 1955. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/266312101#. Accessed 15 April 2024

Postiglione Nadia, 2010. “’It Was Just Horrible’: The Food Experience of Immigrants in 1950s Australia.” History Australia 7 (1): 09.1-09.16. doi:10.2104/ha100009.

Pennay, Bruce (2012) “‘But no one can say he was hungry’: Memories and Representations of Bonegilla Reception and Training Centre”, History Australia, 9:1, 43-63

Pennay, David, ‘Remebering Bongella’, Bongella [website], (2010), https://www.bonegilla.org.au/Education/Resources, accessed 30 April 2024.

Perroni Phillip, ‘interview with author’ [interview], 20 April 2024.

Ricatti, Francesco, Embodying Migrants : Italians in Postwar Australia. Bern: Peter Lang AG International Academic Publishers, 2011. Accessed May 6, 2024. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Unknown photographer, Charcuterie Board with Various Meats and Cheeses, accessed February 2, 2025, JPEG image, https://openverse.org/image/b2ec61c2-3a8b-43a4-94dd-42eaac3674d0.

“Smith’s Weekly” Smith’s Weekly (Sydney, NSW), Saturday, 26 July 1941, 20. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/234607364/25339687.

Tavan, Gwenda, “Long, Slow Death of White Australia,” The Sydney Papers 17, no. 3–4 (2005): 135–139

“THEY SPEAK ITALIANO ON MELBOURNE RADIO” The Herald (Melbourne, Vic. : 1861 – 1954) [image] 6 September 1954: 4. Web. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article248331650, accessed 6 May. 2024

Reflection

This research project explores the culinary journey of Italian migration to Melbourne and its impact on Australian food culture. By analysing historical sources, oral histories and newspaper articles, I traced the evolution of Italian cuisine in Australia – from contraband salami to pantry staples. Growing up in a Greek-Italian household, I was surrounded by rich culinary traditions that painted a vibrant picture of tradition and resilience. My Nonno arrived in Australia in 1956, before officially settling with his family, including my father in 1959. I always wonder how my Nonna and Nonno navigated a land where salami wasn’t a pantry staple and pizza was a foreign concept.

In my research, I explored the transformative power of food in shaping migrant experiences and fostering cultural integration, particularly focusing on Italian migration. By highlighting the resilience of Italian migrants, from their challenges at the Bonegilla Migration Centre to their enduring culinary legacy, I aimed to illuminate how traditional cuisine helps people maintain cultural identity and adapt to new environments.

Through visual representations, such as photographs and articles, I provided both context and emotional connection, capturing the essence of these migration stories. Balancing rigorous historical analysis with personal anecdotes, my research delved into the vibrant culinary journey of Italian migration, celebrating how food bridges generations and continents, and honouring the rich human stories behind our culinary landscape. Buon appetito!

- “No Salami This Time.” the Daily News on 25 March 1955. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/266312101#. ↵

- Gwenda Tavan, "Long, Slow Death of White Australia," The Sydney Papers 17, no. 3–4 (2005): 135–139 ↵

- NOAUTHOR, ‘Food’, Discover Bonegilla [website] (n.d), https://discover.bonegilla.org.au/Suitcase-Trail/Food#, accessed 20 April 2024. ↵

- Richard Bosworth cited in Bruce Pennay (2012) ‘But no one can say he was hungry’: Memories and Representations of Bonegilla Reception and Training Centre, in “History Australia”, 9:1, 49 ↵

- ‘Food’, Discover Bongellia [website], (n.d), https://discover.bonegilla.org.au/Suitcase-Trail/Food#, accessed 20 April 2024. ↵

- Nadia Postiglione, 2010. “‘It Was Just Horrible’: The Food Experience of Immigrants in 1950s Australia.” History Australia 7 (1): 09.1-09.16. doi:10.2104/ha100009. ↵

- Nadia Postiglione, 2010. “It Was Just Horrible’: The Food Experience of Immigrants in 1950s Australia.” History Australia 7 (1): 09.1-09.16. doi:10.2104/ha100009. ↵

- ‘Food’, Discover Bongellia [website], (n.d), https://discover.bonegilla.org.au/Suitcase-Trail/Food#, accessed 20 April 2024. ↵

- ‘Food’, Discover Bongellia [website], (n.d), https://discover.bonegilla.org.au/Suitcase-Trail/Food#, accessed 20 April 2024. ↵

- Ricatti, Francesco. Embodying Migrants : Italians in Postwar Australia. Bern: Peter Lang AG International Academic Publishers, 2011. Accessed May 6, 2024. ProQuest Ebook Central. ↵

- Phillip Perroni, ‘interview with author’ [interview], 20 April 2024. ↵

- Phillip Perroni, ‘interview with author’ [interview], 20 April 2024. ↵

- White 1979 cited in Ricatti, Francesco. Embodying Migrants : Italians in Postwar Australia. Bern: Peter Lang AG International Academic Publishers, 2011. Accessed May 6, 2024. ProQuest Ebook Central. ↵

- Richard White 1979 cited in Ricatti, Francesco. Embodying Migrants : Italians in Postwar Australia. Bern: Peter Lang AG International Academic Publishers, 2011. Accessed May 6, 2024. ProQuest Ebook Central. ↵