11.3 ‘Border Security’: the scapegoating of refugees and asylum seekers in Australia since 2001

Meg Burns

Enter Meg Burns’ exhibition display.

***

In 2001, at the Liberal Party’s campaign launch for the federal election, John Howard lauded Australia as being a nation of ‘generous, open-hearted people taking more refugees on a per- capita basis than any nation except Canada’. To great applause, he then stated ‘But we will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come.’

Many tactics have been deployed over the past two decades to demonise people who come to Australia by boat. ‘Illegals’, ‘queue jumpers’, ‘boat people’ are just some of the terms used by public figures and the media to describe them. Where does such an attitude come from, and how has it been weaponised to justify the treatment of asylum seekers and refugees?

Starting with the Howard years through to the eve of the 2022 federal election, I will explore how successive Australian governments have tried to control the narrative surrounding border protection and boat arrivals through the implementation of dehumanising and inhumane strategies.

See this trailer for the documentary series from 2011, Go Back to Where You Came From, for further insight into differing attitudes towards refugees in Australia (albeit from solely white, privileged perspectives in this instance).

Australia: a settler colony

Before we begin to explore Australia’s horrendous asylum seeker and refugee policies, it is important to discuss the ongoing legacy of racism that traces back to the very foundation of Australia. In her book Cruel Care: A History of Children at Our Borders, Jordana Silverstein cites the Amangu Yamatji historian Crystal McKinnon, who argues that Australia’s practices of border control must not be viewed as extraordinary, as to do so ‘obscures the violence and horror of colonialism’. She continues:

To see contemporary practices of incarceration and detention of asylum seekers as exceptional removes them from the historical and contemporary context of global systems of imperialism and racial capital … It removes the local context and histories too, erasing the ongoing colonial violence against Indigenous people … it is vital to understand detention, incarceration, and other forms of custody as central to colonialism in order for us to analyse these systems, fight against them, and build better societies with Indigenous sovereignty as the foundation.

So-called ‘Australia’ was invaded by the British in the 18th century and subsequently colonised. While the initial act of invasion occurred in the past, the effects and policies of colonisation continue into the present day. Australia remains a settler-colony. It is important to note that in the past three decades more than 400 Indigenous people have died in custody – either being held in prisons or under arrest of the police.

Incarceration of Australia’s Indigenous population is at a record high, despite findings and recommendations from the Royal Commission into Deaths in Custody from 1991. Australia’s inhumane detention system has colonial foundations and plays into a problematic and ongoing racist history.

What is the difference between a refugee and an asylum seeker?

Australia is a voluntary signatory of both the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugee (referred to as ‘the Convention’). Therefore, it is under obligation to offer protection to anyone who meets the Convention definition of a refugee (Mares 2002). Article 1A defines a refugee as a person who:

… owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself to the protection of that country…

As Peter Mares states in his 2002 book Borderline, “Australia has a sophisticated system in place for determining whether or not people meet this definition. A person who comes to Australia in search of such protection is known as an “asylum seeker’”.

The Howard Years, the Tampa Affair and ‘children overboard’, and the subsequent policy changes.

As Guardian journalist Ben Doherty explains, Australia’s current refugee policies have their origins in 2001, when a Norwegian freighter, MV Tampa, changed course to rescue 433 asylum seekers from a leaking vessel en route to Christmas Island. Australia defied international obligations and denied entry to the Tampa. After a week out at sea, the Howard Government sent in the SAS. Instead of receiving food and supplies, 45 troops were dispatched and essentially commandeered the ship. This response was meant to send a message, purportedly to people smugglers and asylum seekers themselves, but arguably more so to the Australian population that John Howard’s government was ‘tough’ when it came to securing the nation’s borders. All this was happening in the lead up to the 2001 federal election campaign. Border protection and migration became an issue of national security – and played into a growing anti-migration sentiment led by Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party. It became a key issue of the 2001 election, especially in the wake of 9/11 which occurred two weeks after the Tampa Affair.

The standoff ceased after Australia paid Nauru, a small island in the Pacific, to take some of the asylum seekers. The government also passed a suite of legislation which excised Christmas Island from the Australian migration zone, effectively making it much more difficult for people arriving by boat to be eligible to apply for protection under Australian law. After the Tampa Affair and Children overboard, and the subsequent introduction of the ‘Pacific Solution’, Howard introduced the Temporary Protection Visa (TPV). Refugees would be given a visa valid for 3 years, after which they would need to reapply. This only applied to refugees who came by boat.

The month following the Tampa Affair, in the lead up to the federal election, another significant incident occurred. Government ministers falsely alleged that asylum seeker parents had thrown their children into the sea in order for them to be able to claim asylum after being rescued. It didn’t happen, yet ministers insisted that it did. These incidents stoked an increasingly hostile sentiment towards asylum seekers arriving in Australia, and set the tone for the next twenty years.

Here is an ABC Lateline report from the lead up to the 2001 federal election discussing the significance of the Tampa Affair on the Australian political landscape:

The Rudd / Gillard Years: 2007 – 2013

The Howard Government’s policies were extremely controversial. The refusal to protect refugees and rejection of Australia’s moral and legal obligation under the Convention were opposed by many. While most of the refugees on Nauru and PNG were resettled within a couple of years, there were still some left when the Labor Party came into power in 2007. In 2008, Labor formally ended offshore processing, as well as Temporary Protection Visas, granting all those with TPVs permanent protection. However, these changes came at a time of an increased number of refugees seeking protection due to wars in both Iraq and Afghanistan displacing millions of people, as well as Tamils fleeing persecution from Sri Lanka. All of this led to an increased number of boat arrivals coming from Indonesia, which spurred the Liberal opposition to spruce a revised punitive ‘solution’ which involved ‘Stopping the Boats’.

The Labor leadership spill of 2010 ousted Kevin Rudd and saw Julia Gillard become Prime Minister under controversial circumstances. Meanwhile, pressure was mounting to do something about the increasing number of asylum seekers arriving by boat. A critical moment occurred when a boat crashed on Christmas Island, killing dozens of people. The Labor government tried to find other ways to deal with the increase in boat arrivals.

After an ill-fated and morally dubious ‘Malaysia Solution’ was deemed by the High Court to be inadequate in fulfilling the requirements of an offshore processing country, an Expert Panel was established by Julia Gillard to provide an alternative asylum seeker policy. With barely a month to provide a compromise policy, its recommendations resulted in the recommencement of offshore processing on Manus Island and Nauru. This would be known as the ‘No Advantage’ policy, which extended the excision policy so that even if a refugee made it to mainland Australia, they would not be eligible to apply for protection.

When Kevin Rudd was reinstated as leader of the Labor Party in 2013, he soon announced that all asylum seekers who arrived by boat would be sent to PNG or Nauru and would never be resettled in Australia, a far cry from his initial mandate in 2007.

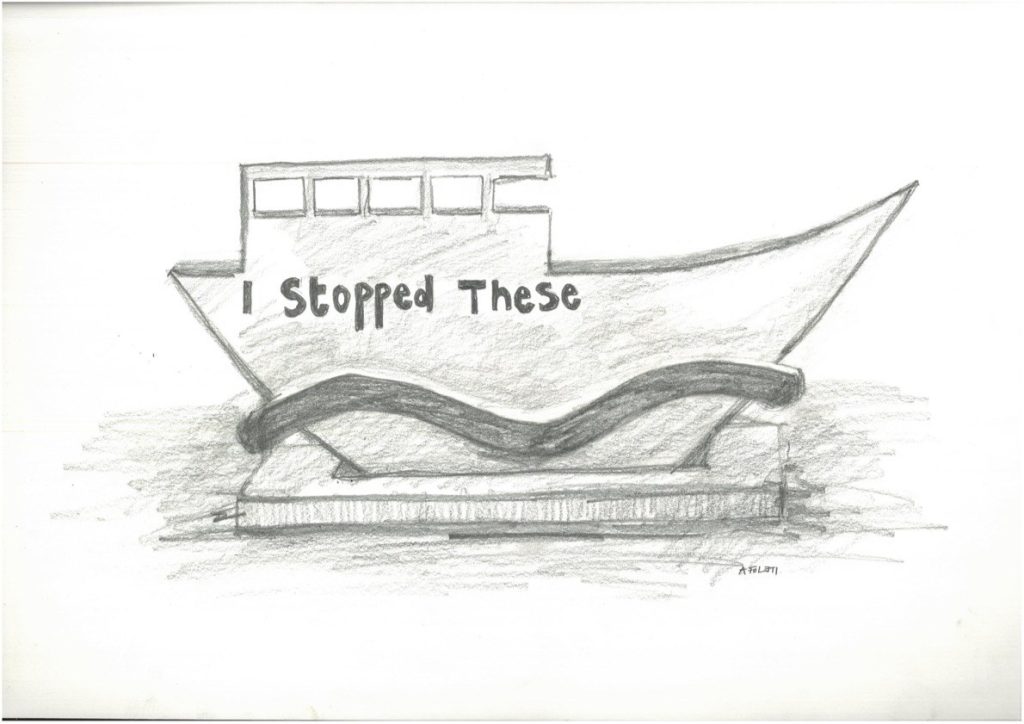

‘Stop the Boats’: Operation Sovereign Borders

After an election campaign based on exploiting the electorate’s fear of migrants and Tony Abbott’s signature slogan of ‘Stop the Boats’, the return of the Liberal Government in 2013 saw the introduction of an even tougher set of policies regarding boat arrivals, indefinite mandatory detention and ‘border protection’. Australia’s refugee policy became amongst the most punitive in the world.

As the Refugee Council of Australia states, these policies included:

- ‘a hardening of the deterrence policies including the continuation of offshore processing, with the introduction of a new quasi-military Operation Sovereign Borders and the establishment of the Australian Border Force

- the introduction of a new and unfair process for determining the claims of those who came by boat, together with the removal of government-funded legal help for those claims, and

- the re-introduction of temporary protection, but this time without the possibility of permanent residence.’

In 2017, after an amendment to the Australian Border Force Act, Section 42 allowed for the imprisonment of up to two years of any doctors or social workers who bore public witness to children beaten or sexually abused, or to acts of rape or cruelty.

As of 2018, 12 asylum seekers had died in the Manus Island, Nauru, and Christmas Island detention centres.

Behrouz Boochani

Behrouz Boochani is a Kurdish refugee residing in New Zealand. He was detained on Manus Island from 2013 until 2019. His book, No Friend but the Mountains, offers a first-hand account of what it was like to be detained indefinitely in what he calls ‘Manus Prison’. Whilst imprisoned, Boochani typed out the chapters on a smuggled mobile phone which he then sent in Whatsapp messages to a friend. These were translated from Farsi to English and published in 2018. He details in beautiful prose and verse his horrific experiences which include a perilous journey to Australia by boat, in which he almost drowned, the feeling of degradation and debasement experienced at the hands of Australian officials, as well as the cramped conditions of the prison and stifling heat of Manus Island. He offers astute insight into what he terms Australia’s ‘Border Industrial Complex’ and the ‘Kyriarchal’ system in place — meaning the system of domination, oppression and submission — which in turn refers to the ‘extent and omnipresence of the torture and control in the prison’.

Here he describes the unbearable conditions of the detention centre:

‘Two open entry-exit points /

Twelve small rooms, approximately one-and-a-half meteres by one-and-a-half-metres /

Flyscreened windows /

Four imprisoned individuals, in bunk beds /

Forced to adapt to each other’s sweaty bodies and the elimination of personal space /

Twelve rusted fans facing the same direction /

Forty-eight individuals /

Forty-eight beds /

Forty-eight foul-smelling mouths /

Forty-eight half-naked, sweaty bodies /

Frightened /

Arguing.’

Boochani perceptively describes the psychological torment and humans rights abuses of what he terms the ‘detention regime’ at Manus Prison where even games like a makeshift backgammon board are forbidden. He writes:

It seemed it was their [the guards] only duty for the entire day: to shit all over the sanity of the prisoners, who were left just staring at each other in distress.

Dirty politics

On the eve of the 2022 election, in a last-ditch effort by Scott Morrison to sway the election result in his favour, voters in marginal seats received a text message from the Australian Border Force informing them that a vessel had been intercepted in ‘an attempt to enter Australia from Sri Lanka.’

Australia’s refugee policies throughout the 21st century can only be described as cynical, using tactics to exacerbate and exploit the xenophobia of the electorate which in turn has justified the inhumane treatment of people seeking asylum. If one is to hold the idea of ‘Australian values’ – kindness, compassion, the fair-go – who poses more of a threat to these values? I would argue it is the politicians mandating racism, torture and abuse in the name of ‘border security’, rather than people who have risked everything to seek asylum.

Bibliography

Primary sources

Boochani, Behrouz, Tofighian, Omid, and Flanagan, Richard. No Friend but the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison. Australia: Picador Australia, 2018.

Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Australian Border Force Amendment (Protected Information) Bill 2017, (Canberra, 11 September 2017).

Evans, Chris, Department of Immigration and Citizenship. Last refugees leave Nauru (Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Canberra, 8 February 2008).

Go Back to Where You Came From Series 2 Trailer, (SBS Australia, July 26 2012), https://www.youtube.com/watch? v=XvmHTDBXvL0 accessed 18 May 2024.

Howard, John, election speech, delivered at Sydney, NSW, October 28th, 2001. https://electionspeeches.moadoph.gov.au/ speeches/2001-john-howard accessed 12 Apr. 2024.

There is no way you will make Australia home, (Australian Customs, 11 Apr. 2014), https://www.youtube.com/watch? v=1vCQHps_k3E accessed 18 May 2024.

No advantage to come by boat: Australian Government, (ABC News, 3 Sep. 2012), https://www.youtube.com/watch? v=2T3sEEtQWjY accessed 18 May 2024.

Tampa – ABC Open Archives – 2001 (A Glimpse of the Past with Super Resolution (YouTube), December 5 2021), https:// www.youtube.com/watch? v=nR0FBY2uZIg&embeds_referring_euri=https%3A%2F %2Fsway.cloud.microsoft%2F&embeds_referring_origin=https%3A %2F %2Fsway.cloud.microsoft&source_ve_path=MzY4NDIsMjM4NTE& feature=emb_title accessed 18 May 2021.

Secondary sources

Allam, Lorena, ‘We should all be furious’: Aboriginal people make up record 31% of adult prison population in NSW’, The Guardian, 14 May 2024, accessed 18 May 2024.

Doherty, Ben, ‘The Tampa Affair, 20 years on: the roots of Australia’s hardline asylum seeker and refugee policy’, The Guardian, 25 August 2021, https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=_SoghjAo8eg, accessed 18 May 2024.

Greene, Andrew, ‘Scott Morrison instructed Border Force to reveal election day asylum boat arrival’, ABC News, ‘Federal Election 2022 – Australia Votes’, 27 May 2022, https://www.abc.net.au/ news/2022-05-27/scott-morrison-instructed-border-force- election-day-boat/101101464, accessed 20 May 2024

Khalil, Shaimaa, ‘Aboriginal Australians ‘still suffering effects of colonial past’, BBC News, 17 July 2020, accessed 18 May 2024.

Mares, Peter, Borderline: Australia’s Treatment of Refugees and Asylum-seekers, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2001.

McKinnon, Crystal, ‘Expressing Indigenous sovereignty: the production of embodied texts in social protest and the arts’, PhD thesis, La Trobe University, 2018.

Refugee Council of Australia, ‘Australia’s asylum policies’, [website], (27 March 2024). https://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/ asylum-policies/4/#https://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/timeline/ #, accessed 18 May 2024.

Rourke, Alison, ‘Tony Abbott, the man who promised to ‘stop the boats’, sails to victory’, The Guardian, 8 September 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/ sep/07/australia-election-tony-abbott-liberal-victory, accessed 20 May 2024.

Silverstein, Jordana, Cruel Care: A History of Children at Our Borders, Monash University Publishing, Melbourne, 2023.