5.1 Author positionality

As a Pasifika researcher of Tongan descent, it is right that I make myself transparent and known to readers, particularly to those who are Pasifika researchers themselves. This is culturally appropriate.[1]

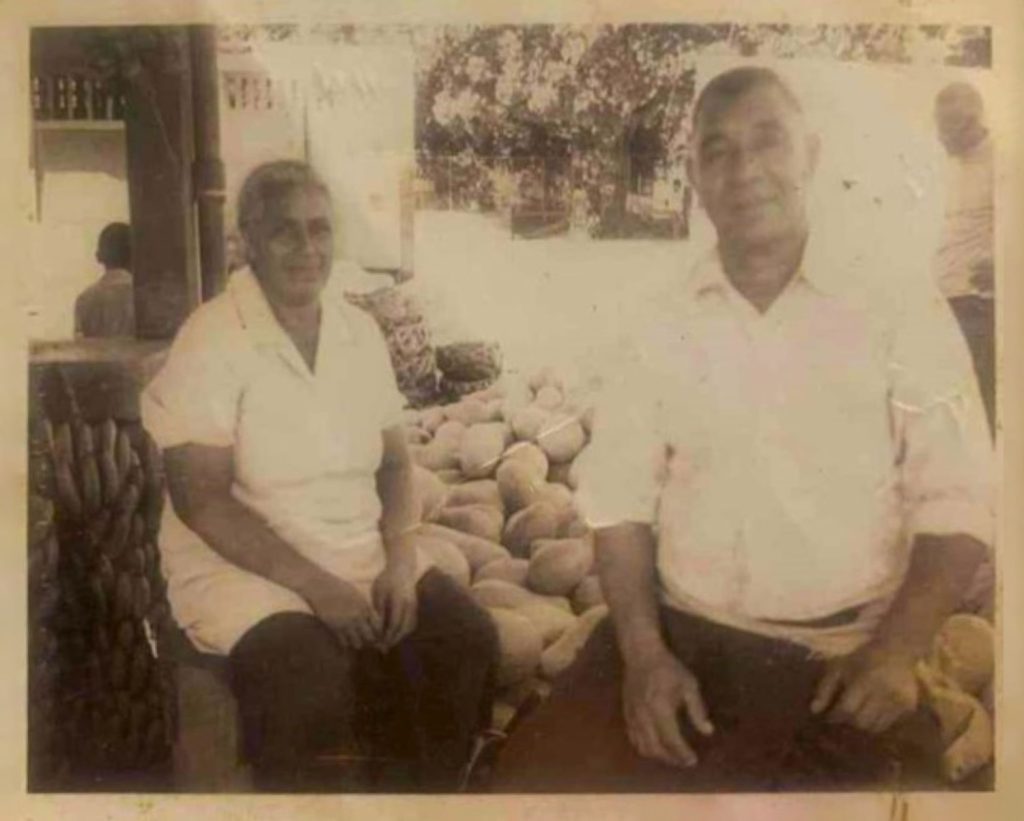

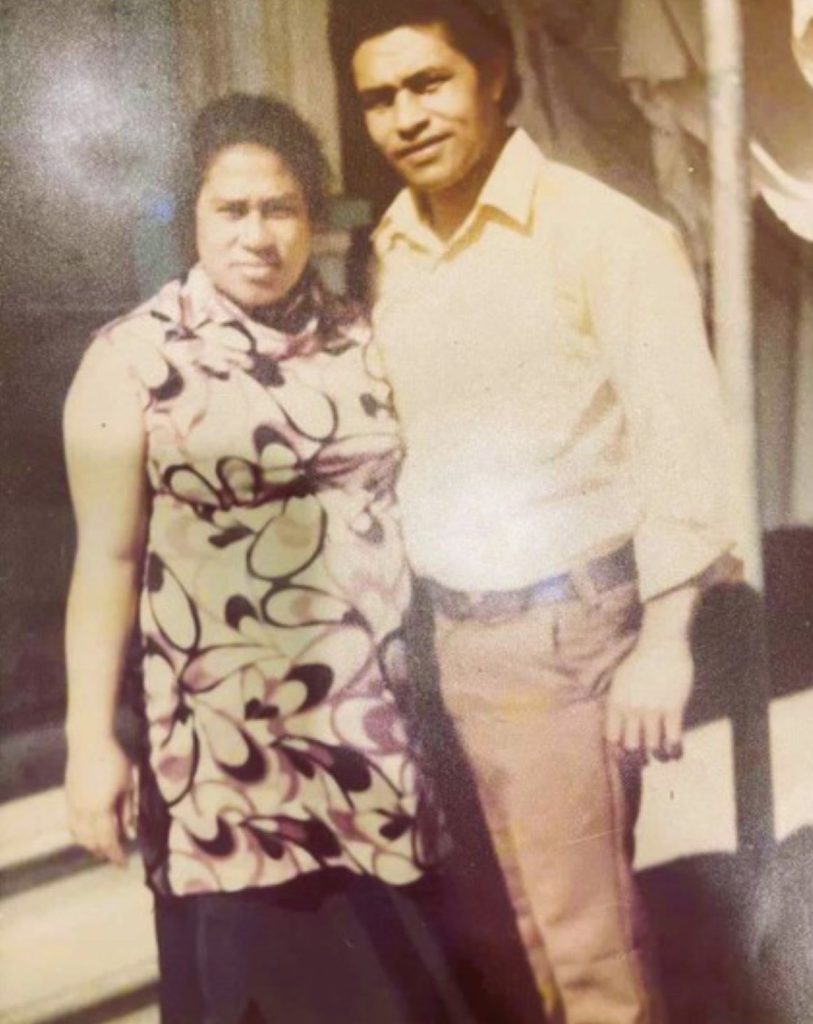

My paternal grandparents, (Figure 1) Semisi ‘Ilaiū (grandfather) is from the village of Mu‘a Tatakamotonga on the main island of Tongatapu and ‘Ilaisaane ‘Ilaiū (née Tu‘imoala, grandmother) is from the village of Pukotala on Ha‘ano island, Ha‘apai group directly west of the Tonga Trench (with ancestral ties to Fiji). My maternal grandparents, Moho Leau (grandfather, with ancestral ties to Sāmoa) is from the village of Houma, Tongatapu and ‘Ana Malia Fisi‘ihone Akauola (née Halangahu, grandmother, with ancestral ties to Uvea) is from Ha‘alalo, Tongatapu (Figure 2).

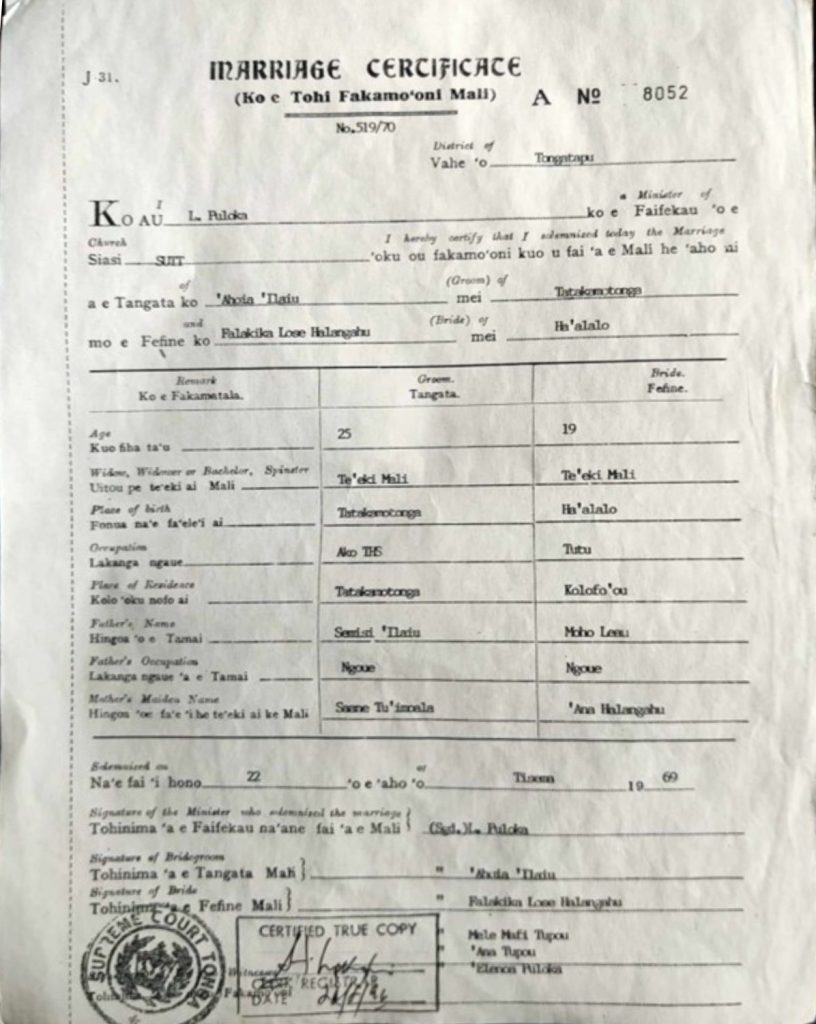

My father ‘Ahoia ‘Ilaiū first met my mother Falakika Lose Halangahu while boarding in Nuku‘alofa (the capital city of Tonga) as a student at Tonga High School. After courtship, they were married on 22 December 1969 in Tongatapu (see their marriage certificate in Figure 3) and travelled to the outer island of Vava‘u, where my father was teaching. They later returned to the main island of Tongatapu shortly before the birth of their first child (1972).

It was during this time that they decided it would be easier for them to provide a better life for their family if they migrated overseas. They took advantage of the short-term work visas on offer to Pacific Islanders and moved to Aotearoa NZ (Figure 4), where I was later born in 1974. My parents were then able to apply for Aotearoa NZ citizenship on the grounds that they had a child born in the country, as well as the fact they had purchased their first property there, allowing them to settle and raise a family in this newfound homeland.

In the early 1990s I met Leaula Thom Faleolo, the eldest son of Aufa‘i Leaula Saolotoga Faleolo from Saleaula and Falelima, Sāmoa, and Malia ‘Alosia Faleolo (nee Suafoa), from Leulumoega, Sāmoa. Thom and I were studying at the University of Auckland when we became good friends at 18 years of age. We married on 22 November 1997 in Auckland and later had six children: Israel, Sh’Kinah, Angels, Nehemiah, Lydiah, and Naomi. Thom and I chose to live in Ōtara, where we purchased our first two properties right next door to my parents; there our growing family was born and raised. We built our careers in education and research, researching and studying part time to complete higher qualifications while teaching full time in local secondary schools in South Auckland (2002–2015). After much conversation, prayer and consideration of our options, we decided to sell up our homes to move to Brisbane; we hoped for a healthier lifestyle, better opportunities and higher education for our family. As I write this chapter, it’s been almost a decade since we moved to Australia; several of our goals have been achieved here, some are still in progress, and holistically our family’s life has been good. We count our blessings each time we think about our shared migration story (Figure 5).

In 2015 I began a PhD study of Pasifika trans-Tasman migration and the correlation between their experiences and perspectives of wellbeing. The findings of this study revealed that Pasifika (including Tongans’) narratives and understandings of their migration are holistic and that their mobility is collectively inspired by their holistic dimensions of wellbeing. In 2020 these insights helped shape the objectives of my postdoctoral study of Pasifika mobilities to and through Australia. An interesting outcome of the earlier part of the study was the impact of COVID-19 on the collective mobility of Tongans that I was working in partnership with across Australia, Aotearoa NZ and the US. The physical restrictions on their connectivity enhanced and became the catalyst for further sociocultural connectivity online – strengthening the intergenerational and multigenerational sharing of spiritual, social and cultural knowledge and heritage. Four years later, in 2024, I have been given opportunities through ongoing and new research work to study Pasifika migration and mobilities through various lenses, including seasonal food workers’ pathways into Australia and intra-movements within Australia’s states and territories, as well as a continuation of the study of Pasifika mobilities to and through Australia to other Pacific rim nations (Aotearoa NZ and the US) and further afield to Asia and Europe.

It is my hope to capture the nuances of Tongan mobility histories that are often left untold or have been told incorrectly. This chapter will reflect the gleanings of meaning making and understandings that I have been privy to hearing and experiencing in my participant–observer research work over the years.

- Inez Fainga‘a-Manu Sione, Ruth (Lute) Faleolo, and Cathleen Hafu-Fetokai. “Finding Harmony Between Decolonization and Christianity in Academia,” Art/Research International: A Transdisciplinary Journal, Special Issue: (Re)crafting Creative Critically Indigenous Intergenerational Rhythms and Post-COVID Desires, 8, no. 2 (2024): 519–546; Ruth (Lute) Faleolo, Edmond Fehoko, Dagmar Dyck, Cathleen Hafu-Fetokai, Gemma Malungahu, Zaramasina L. Clark, Esiteli Hafoka, Finausina Tovo, and David T. M. Fa‘avae. “Our Search for Intergenerational Rhythms as Tongan Global Scholars,” Art/Research International: A Transdisciplinary Journal, Special Issue: (Re)crafting Creative Critically Indigenous Intergenerational Rhythms and Post-COVID Desires, 8, no. 2 (2024a): 663–704. ↵