10.2 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People in the First World War

Matilda Murray-White

Read Matilda Murray-White’s Wikipedia entry.

***

First Nation Australians fought in Australia’s Imperial Forces (AIF) during the First World War especially in the Australia and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC). These servicemen initially could not enlist in the AIF due to being Aboriginal, but as the war progressed over 1000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders enlisted to serve a country in which they were not yet recognised as citizens.

Background

First Nations Australians

Australia has been home to its Indigenous population for over 65,000 years.[1] This population is the oldest surviving culture in the world with over 500 language groups and nations that cared for country. British colonisation began in January 1788 with the landing of Captain Arthur Phillip and the First Fleet and the establishment of the colony of New South Wales. In the following 120 years, Australia was federated in 1901 and became an established country in the British Commonwealth.

World War I

The First World War broke out with the assassination of Franz Ferdinand on the 8th of July and the Austrian declaration of war on Serbia in late July. Following this, Britain declared war on Germany following its invasion of Belgium in support of Austro-Hungary. With Britain’s declaration of war on Germany, this pulled Australia and other British colonies in the Commonwealth were pulled into the War.

Enlistment

Exclusion

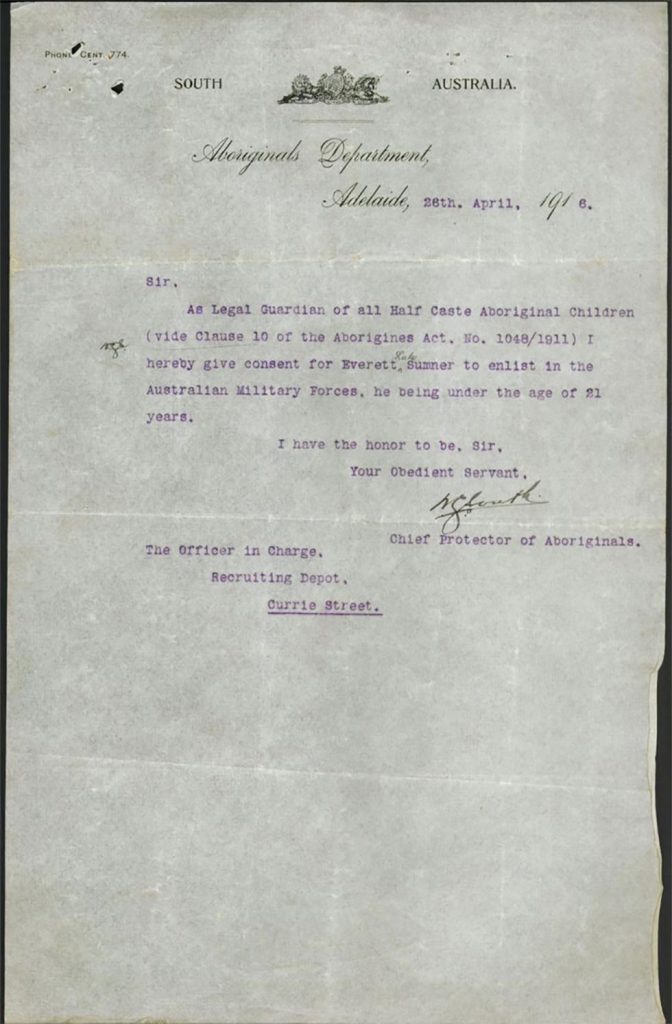

At the outbreak of World War I, Australia sent troops to fronts in Europe in the First Australian Imperial Forces. General enlistment was used, allowing for volunteers to sign up to join the Forces. The Defence Act of 1903 prohibited the enlistment of any Aboriginal people into the Australian Imperial Forces, citing that only people of “substantially of European origin or descent”.[2] could enlist. Despite this, around 1000 First Nations people managed to enlist to fight with the Australian Imperial Forces.[3] While the discrimination that Indigenous Australians faced when trying to enlist was widespread, First Nations people were able to find loopholes to enlist and some enlistment officers allowed them to enlist despite their aboriginality. Due to the Protection Act from each state’s Protection Board, which controlled the lives of Aboriginal people, they needed to obtain permission to try and enlist. Figure 1 shows a consent form from the South Australian Chief Protector allowing Everett Luke Sumner, a Ngarrindjeri man who enlisted in 1916.[4]

Motivation

The motivations for Aboriginal people to enlist were wide ranging. Early understandings of the First Nations motivations to go to war were mainly surrounding financial gain, with privates earning 5 shillings a day plus a shilling of deferred pay that they would receive following their discharge. This was a generous wage compared to that of a First Nations worker in Queensland of 7 shillings a week.[5] Yet, focusing on the financial motivations of going to war fails to highlight the agency of First Nations people. Going to fight in the war provided an opportunity for mobility and travel out of Australia, something that was not afforded to Aboriginal Australians.[6] Furthermore, the want to enlist may have been fuelled by friend or family also enlisting, or the opportunity for adventure. Another motivation for enlistment for Aboriginal people was very similar to White Australians: patriotism for their country, to serve and protect. This led to the belief that going to war for Australia would aid in the fight for citizenship and recognition.

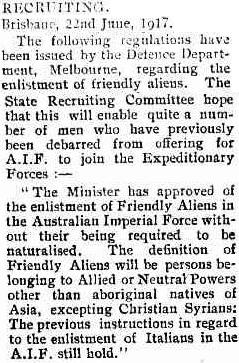

Enlistment Amendment

In 1917, following the catastrophic losses at Gallipoli and the Somme, and the failure of the 1916 conscription referendum, amendments were made to the 1903 Defence Act.[7] The amendments allowed that “Half-castes may be enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force provided that the examining Medical Officers are satisfied that one of the parents is of European origin.”[8]

Experience

The experience in the AIF and on the front lines during WWI for First Nations Australians was both drastically different and similar to the non-Indigenous soldiers who fought besides them. The mentality of war created an attitude of ‘brotherhood’ and ‘us vs the enemy’ which allowed for First Nations soldiers to become a part of the ‘us’, fighting for a common cause. This led to the idea of mateship born from the ANZACs and the creation of the ANZAC legend. First Nations people experienced many new freedoms whilst on the war front and were often equally treated as they received equal pay and often treatment.[9] Aboriginal soldiers were not living under the difficult restrictions of the Protection Acts as they had been in Australia and lived with varying degrees of freedom on the frontlines.

Yet despite this, Aboriginal Australians still faced widespread discrimination and racism on the front lines. The Australian Imperial Forces still reflected the ‘White Australia Policy’.[10] Aboriginal soldiers experienced similar racial discrimination to that they experienced at home. This shows how the prejudices of White Australian society were transplanted onto the front lines and ran deep within the AIF.[11] In situations where Aboriginal soldiers were championed for acts of bravery or heroism, their Aboriginality was always highlighted, showing how First Nations men were always first judged by their colour, rather than their achievements.[12]

Coming Home

Following the end of the war in 1918, the experience of Aboriginal service people was starkly different from that of White Australians. Those First Nations men who had risked their lives for a country that still did not see them as citizens, were regarded as heroes to their families and communities.[13] A shared experience of the war between First Nations Australians and White Australians was the physical and mental trauma they had all gone through, with many experiencing shell shock and PTSD in the years following.[14] White returned soldiers from World War I were given land in repatriation efforts. Each state had its own Soldier Settlement Schemes, but they all involved the repatriation of land through sale or rent to returned soldiers.[15] First Nations soldiers were not given this option for land. The land that was offered to these returned servicemen was had been from First Nations people with the White settlement of Australia. Returned Aboriginal servicemen were rejected from Returned Service Leagues and omitted from on honour rolls.[16] On their return to Australia following the war, many of the First Nations servicemen went back to live controlled lives on missions and reserves, as well as living under the control of each state’s Protection Act, which controlled all aspects of their lives. As Aboriginal activist William Cooper wrote in his 1939 letter to Federal Minister for the Interior, John McEwan:

I am a father of a soldier who gave his life for his King on the battlefield…those that survived were pushed back to the bush, to resume the status of aboriginal…the aboriginal now has no status, no rights, no land… nothing to fight for but the privilege of defending the lank which was taken from him by the white race without compensation or kindness.[17]

One of the main motivations for First Nations people to enlist to fight in World War I was in hope of the acceleration of recognition of citizenship for Indigenous people.[18] Yet, the hundreds of lives sacrificed by First Nations people in war did not aid in the fight for citizenship, and Indigenous people were not recognised as citizens and in the constitution of Australia until the 1967 Referendum.

The ANZAC Legend

World War I led to the creation of one of Australia’s largest national identities, the concept of the ‘Anzac Legend’. According to this legend, Australia was ‘born’ on ANZAC Cove . The legend is embodied by the young man, mirroring the young nation, who went to war to defend his country. It highlights ideas of hip, larrikinism and courage, all qualities that embody what it is to be ‘Australian’.[19] The ANZAC legend however fails to recognise and include First Nations despite their crucial involvement in the war effort, therefore erasing them from the ANZAC myth itself.[20] The ANZAC legend is a national identity that White Australia prides itself on and it’s a foundational collective identity that all Australians should feel like they can subscribe to. Yet, the legend fails to consider experience of First Nations soldiers both during and after the war, as well as the treatment of Aboriginal Australians since settlement, especially as the legend neglects to reflect on First Nation population prior to British Settlement.

Legacy

In the decades following World War I, recognition of the First Nations participation in the war has slowly grown through physical representation in monuments as well as in the public understanding of the ANZACs. ANZAC Day has seen an increasing amount of First Nations veterans march, in representation of the Indigenous Australians who have risked their lives for Australia. These marches have allowed First Nations servicepeople to receive recognition of their sacrifice as well as showing the broader Australian community the impact that First Nations people had in the ANZACs and in the wider Australian defence community.[21]

See also

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Cooper, William , “80: William Cooper, Secretary, Australian Aborigines’ League, to the Minister for the Interior, John McEwen, Canberra, 3 January 1939,” in Thinking Black: William Cooper & the Australian Aborigines’ League, by Bain Attwood, Andrew Markus, and Alfred Turner, 1st ed. (Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2004), 112–113, doi: 10.3316/informit.0855754591.

National Archives of Australia: Defence Board; Australian Army Orders, Gazette notices and Military Board instructions, 01 Jan 1905 – 31 Dec 1951; Military Orders (1 to 277) – January to June 1917, Jan 1917 – Jun 1917.

National Archives of Australia: Australian Imperial Force, Base Records Office; First Australian Imperial Force Personnel Dossiers, 1914-1920; SUMNER Everett Luke: Service Number – 3626, 1914-1920

‘Recruiting’, Bowen Independent (QLD), July 14 1917, 1, in Trove [online database], accessed 13 May 2024

Sharp, Karl, Honour recognition respect, lest we forget” banner, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ANZAC march in Redfern, 2007, in Trove [online database], accessed 17 May 2024

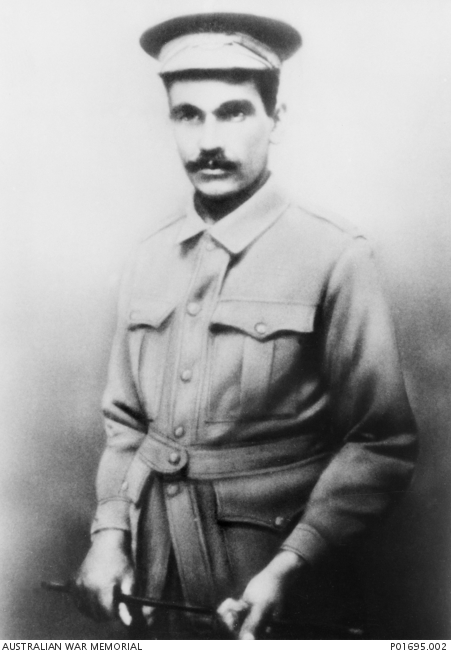

Unknown, Studio portrait of an Aboriginal serviceman, 5459 Corporal (Cpl) Harry Thorpe MM, c 1916, P01695.002, Australian War Memorial

Secondary Sources

Broome, Richard. Aboriginal Victorians: A History since 1800 (St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 2005).

Cadzow, Allison, and Mary Anne Jebb. Our Mob Served: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories of War and Defending Australia (Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2019).

Clancy, D. A. “Who Paid the Price? Wider Implications of the Post-Great War Soldier Settlement Scheme in Queensland.” History Australia 18, no. 3 (July 2021): 526–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/14490854.2021.1956334.

Clarkson, Chris, Zenobia Jacobs, Ben Marwick, Richard Fullagar, Lynley Wallis, Mike Smith, Richard G. Roberts, et al. “Human Occupation of Northern Australia by 65,000 Years Ago.” Nature (London) 547, no. 7663 (2017): 306–310. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature22968.

Cooper, William. “80: William Cooper, Secretary, Australian Aborigines’ League, to the Minister for the Interior, John McEwen, Canberra, 3 January 1939.” In Thinking Black: William Cooper & the Australian Aborigines’ League, by Bain Attwood, Andrew Markus, and Alfred Turner, 112–113, 1st ed. (Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2004). https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.0855754591.

Drozdzewski, Danielle. “Does Anzac Sit Comfortably within Australia’s Multiculturalism?” Australian Geographer 47, no. 1 (2016): 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2015.1113611.

Gibson, Padraic John. “Imperialism, ANZAC Nationalism and the Aboriginal Experience of Warfare.” Cosmopolitan Civil Societies 6, no. 3 (2015): 63–82. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v6i3.4190.

Hall, Robert. The Black Diggers Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders in the Second World War. 2.. (Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 1997).

Huggonson, David. “Aborigines and the Aftermath of the Great War.” Australian Aboriginal Studies (Canberra, A.C.T.: 1983) 1, no. 1 (1993): 2–9.

Jackomos, Alick. Forgotten Heroe : Aborigines at War from the Somme to Vietnam (South Melbourne, Vic: South Melbourne, Vic : Victoria Press, 1993).

Maynard, John. “Missing Voices: Aboriginal Experiences in the Great War.” History Australia 14, no. 2 (2017): 237–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/14490854.2017.1319743.

Maynard, John, “The First World War.” In Serving Our Country: Indigenous Australians, War, Defence and Citizenship, by Joan Beaumont and Allison Cadzow (Sydney: New South Publishing, University of New South Wales, 2018).

McDonnell, Siobhan, and Mick Dodson. “Race, Citizenship and Military Service.” In Serving Our Country: Indigenous Australians, War, Defence and Citizenship, by Joan Beaumont and Allison Cadzow (Sydney: New South Publishing, University of New South Wales, 2018).

Riseman, Noah. “Introduction: Diversifying the Black Diggers’ Histories.” Aboriginal History 39 (2015): 137–142. https://doi.org/10.22459/AH.39.2015.06.

Scarlett, Philippa. “Aboriginal Service in the First World War: Identity, Recognition and the Problem of Mateship.” Aboriginal History 39 (2015): 163–181. https://doi.org/10.22459/AH.39.2015.08.

Stanley, Peter. “‘He Was Black, He Was a White Man, and a Dinkum Aussie’: Race and Empire in Revisiting the Anzac Legend.” In Race, Empire and First World War Writing, by Santanu Das (West Nyack: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Reflection

My project surrounded First Nations involvement in World War I, and particularly the ANZACs. I chose this topic as I have an interest in 20th century history particularly the World Wars, and First Nations history. The public knowledge of these major world events is often very Eurocentric, and I even saw this within my own education and tertiary research. I wanted to consider the stories of First Nations individuals who fought in World War I and the aftermath and how they have been silenced. I was drawn further into this topic by how divisive it was and the power it held to challenge vast issues within the nation. The ANZAC legend was born from the First World War. Throughout my research of this topic, I noticed how much the lived experience of First Nations soldiers challenged the legend. This topic made me to challenge my own thinking of World War I and allowed me to continue to consider the voices not heard when researching areas in the future.

- Chris Clarkson et al., “Human Occupation of Northern Australia by 65,000 Years Ago,” Nature (London) 547, no. 7663 (2017): 306–310, doi: 10.1038/nature22968. 1. ↵

- Alick Jackomos, Forgotten Heroes: Aborigines at War from the Somme to Vietnam (South Melbourne, Vic: South Melbourne, Vic : Victoria Press, 1993). 10 ↵

- Noah Riseman, “Introduction: Diversifying the Black Diggers’ Histories,” Aboriginal History 39 (2015): 137–142, doi: 10.22459/AH.39.2015.06. 137. ↵

- NAA: B2455, 11605042. ↵

- David Huggonson, “Aborigines and the Aftermath of the Great War,” Australian Aboriginal Studies (Canberra, A.C.T.: 1983) 1, no. 1 (1993): 2–9. 3. ↵

- John Maynard, “Missing Voices: Aboriginal Experiences in the Great War,” History Australia 14, no. 2 (2017): 237–249, doi: 10.1080/14490854.2017.1319743. ↵

- John Maynard, “The First World War,” in Serving Our Country: Indigenous Australians, War, Defence and Citizenship, by Joan Beaumont and Allison Cadzow (Sydney: New South Publishing, University of New South Wales, 2018). 56. ↵

- NAA: MP390/10, 1917 PART 1. ↵

- Richard Broome, Aboriginal Victorians: A History since 1800 (St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 2005). 199-200. ↵

- Peter Stanley, “‘He Was Black, He Was a White Man, and a Dinkum Aussie’: Race and Empire in Revisiting the Anzac Legend,” in Race, Empire and First World War Writing, by Santanu Das (West Nyack: Cambridge University Press, 2011). ↵

- Philippa Scarlett, “Aboriginal Service in the First World War: Identity, Recognition and the Problem of Mateship,” Aboriginal History 39 (2015): 163–181, doi: 10.22459/AH.39.2015.08. 171. ↵

- Scarlett, “Aboriginal Service”, 170. ↵

- Maynard, “The First World War”. ↵

- Maynard, “The First World War”, 62. ↵

- D. A. Clancy, “Who Paid the Price? Wider Implications of the Post-Great War Soldier Settlement Scheme in Queensland,” History Australia 18, no. 3 (July 2021): 526–543, doi: 10.1080/14490854.2021.1956334. ↵

- Padraic John Gibson, “Imperialism, ANZAC Nationalism and the Aboriginal Experience of Warfare,” Cosmopolitan Civil Societies 6, no. 3 (2015): 63–82, doi: 10.5130/ccs.v6i3.4190. 64. ↵

- William Cooper, “80: William Cooper, Secretary, Australian Aborigines’ League, to the Minister for the Interior, John McEwen, Canberra, 3 January 1939,” in Thinking Black: William Cooper & the Australian Aborigines’ League, by Bain Attwood, Andrew Markus, and Alfred Turner, 1st ed. (Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2004), 112–113, doi: 10.3316/informit.0855754591. ↵

- Siobhan McDonnell and Mick Dodson, “Race, Citizenship and Military Service,” in Serving Our Country: Indigenous Australians, War, Defence and Citizenship, by Joan Beaumont and Allison Cadzow (Sydney: New South Publishing, University of New South Wales, 2018). 35. ↵

- Danielle Drozdzewski, “Does Anzac Sit Comfortably within Australia’s Multiculturalism?” Australian Geographer 47, no. 1 (2016): 3–10, doi: 10.1080/00049182.2015.1113611. ↵

- Robert Hall, The Black Diggers Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders in the Second World War., 2.. (Canberra: Canberra : Aboriginal Studies Press, 1997). ↵

- Allison Cadzow and Mary Anne Jebb, Our Mob Served : Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories of War and Defending Australia (Canberra, Australia : Aboriginal Studies Press, 2019). 343-344 ↵