7.1 A brief history of the miner’s cottage

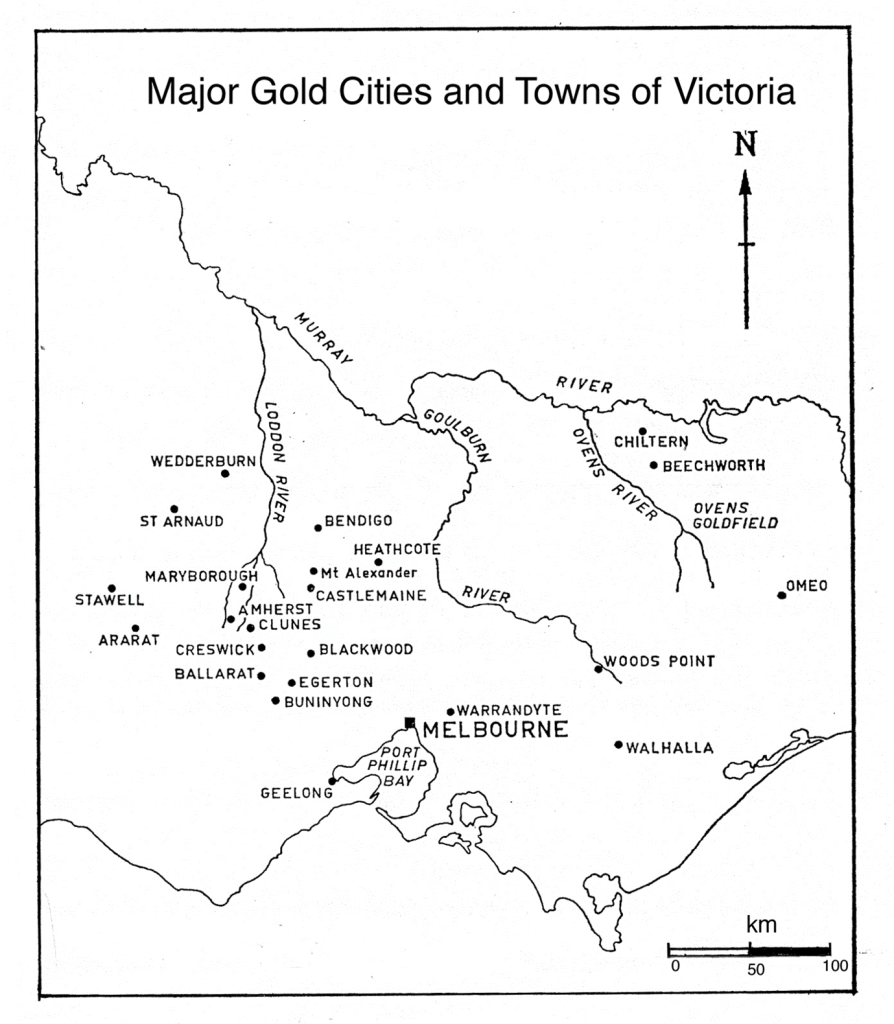

To understand how the urban shape and housing forms of Bendigo evolved, we need to understand the history of Bendigo’s mining industry. While the built form of 19th-century Bendigo (and other goldfields) was largely a product of quartz mining, legislative developments trialled in the alluvial phase set a pattern of residence on Crown land. Gold was found on Dja Dja Wurrung land. The Indigenous owners of this land were ruthlessly pushed aside across northern Victoria by squatters in the 1830s and 1840s. When gold was discovered, the squatters on auriferous (gold-rich) land in turn found themselves dispossessed of their sheep runs by the colonial government. Surveyors moved onto the goldfields, laid out towns and villages, surveyed cadastral areas for agriculture and critically reserved large areas of Crown land as auriferous land. This Crown land became a major resource for housing. From 1871 the larger urban districts on the Bendigo goldfield were the City of Sandhurst (Bendigo from 1891) and the Borough of Eaglehawk (see Map 1 for the location of Bendigo). These two municipalities were surrounded by the rural shires of Marong, Huntly and Strathfieldsaye. In 1994 these areas became part of the City of Greater Bendigo.[1]

Gold was discovered in late 1851 and the first great rush occurred in the summer of 1852. As the great Australian historian Geoffrey Serle demonstrated, migrants arriving in search of gold transformed Victoria from a minor sheep-farming outpost to a bustling colony; Melbourne for a generation was Australia’s major city.[2] From 1852 to the mid-1850s, most alluvial mining was undertaken by teams of three or four men who dug shallow shafts into the pipe clay of Bendigo and recovered the gold with simple hand technology. From the mid-1850s, horse-driven puddling machines were used to strip the topsoil, and vast volumes of soil were treated to win the smaller parcels of gold not recovered by the first prospectors. Puddling distributed miners across the Bendigo goldfield. At the 1857 census the largest concentration of miners was, not surprisingly, in and around the Borough of Sandhurst. Outside the borough boundaries there were large concentrations of alluvial miners to the south, as well as to the north in the Epsom-Huntly district. These workers, known as ‘puddlers’, and their families lived on Crown land. Four years later when the next census was taken, alluvial mining remained the dominant mode, and puddlers were again widely distributed across the goldfield. Members of Victoria’s first Legislative Assembly legislated for a ‘miner’s right’. For an annual fee of £1, prospectors were permitted to ‘mine for gold upon any waste lands of the Crown’ and to occupy a portion of this land for residence. This provided cheap land on which miners erected rudimentary housing. In 1857 over 80 per cent of housing was simply labelled in the census as a one-roomed hut or tent.[3]

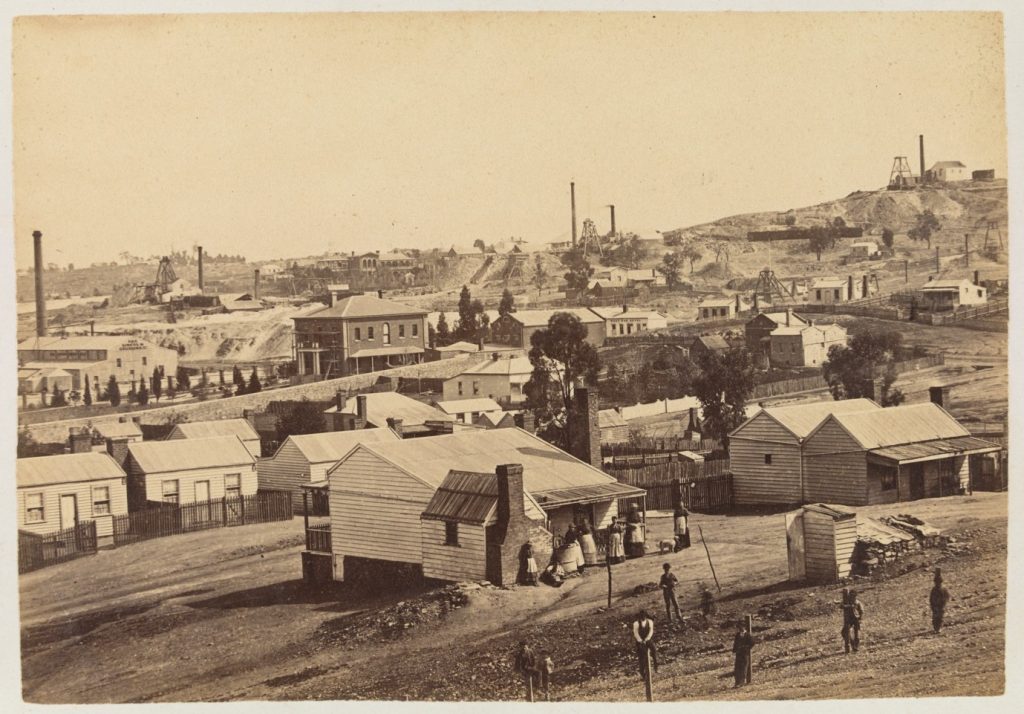

From the first days of the alluvial rushes, prospectors hacked away at surface outcrops of quartz with primitive gads (pointed picks) and hammers. A stable industry developed slowly from the late 1850s. Initially, cooperative parties worked quartz reefs. As shafts were sunk deeper capital was required and many struggling claims were floated as public companies. A handful of fortunate reefers struck rich deposits close to the surface and became mine owners, and local businessmen invested commercial profits into mining. By the mid-1860s a small elite of successful quartz reefers and investors can be identified. In the late 1860s these men began to build houses appropriate to their new won wealth. One of the defining features of the Bendigo goldfield was the propensity of these mine owners and speculators to build near their mines, and their houses, usually of brick and stone, were spread across the quartz mining districts of the Bendigo goldfield. These men were able to use the provisions of the Mining Statute of 1865 and the Amending Land Act 1865 to buy freehold land.

In 1865, as Bendigo made the transition from alluvial to quartz reefing, the Victorian legislature overhauled mining law. A new bill set the ground rules for cheap housing for the mining population. Under section 4 of the Mining Statute of 1865, taking out a miner’s right for 5 shillings per year (reduced from £1) permitted the holder to occupy on any goldfield Crown land for a residence. The area was to be set by local by-laws. The act permitted the holder to erect a dwelling and remove timber. When the Crown sold this land, always at auction, the value of improvements was added to the upset price of £1 per acre. If the occupier was the highest bidder, a valuation of improvements was deducted from the purchase price. Applying to transfer Crown to freehold land favoured those with capital; land put up for sale was offered to all comers by competitive auction. This system of tenure was in place until 1881 when the Miner’s Residence Area Bill was legislated.

A gold boom in the early 1870s transformed the socio-geography of Bendigo. Over the five years from 1871 to 1876 the Bendigo mines were highly profitable, and employment was buoyant. As alluvial mining struggled, prospectors moved out of mining, and many left the community. During the years of alluvial mining the search for gold encouraged men from diverse backgrounds to try their luck as prospectors. With the rise of quartz mining, the industry was dominated by a new type of miner, recruited from the metal mines of Cornwall in the south-west of England and to a lesser extent from Germany. At the same time many Irishmen and other migrants, with little hard-rock mining experience, left the industry and often the community. The migrants of the 1870s had no illusions that fortunes were to be won; they came looking for waged work and brought with them wives and children. There was a pressing need to quickly provide housing. Employment conditions in the mines became precarious from the 1880s. Employees suffered from bouts of unemployment and frequently worked on a form of contracting known as tributing.[4]

The ready availability of Crown land and the weatherboard cottage was the means of creating instant suburbs. The itinerant prospector used the miner’s right to provide land to erect temporary buildings of canvas, slab, stone and bark. With the arrival of the wage-earning family miner these vernacular materials were replaced by factory-sawn timber frames and weatherboards. Although most land in the centre of the city was alienated in land auctions through the 1850s, land near and adjoining mining leases remained in Crown ownership. Large areas in neighbouring shires such as Marong were deemed auriferous and available for occupation under a miner’s right. Miners, for a nominal rent of 5 shillings per year, could take up quarter-acre allotments and erect cottages. Many Cornish miners came from a tradition of owner building on mining leases, and the miner’s residence area permitted them to transport this practice to their new homes in Bendigo.[5]

Alluvial mining dispersed miners across the whole Bendigo mining field; quartz reefs were concentrated on the western side of the surveyed centre of Bendigo and ran in a north-south direction. Miners’ residences were spread out along the main lines of reef. On the New Chum reef line, miners’ houses extended from Spring Gully Reservoir in the south to north of the town of Eaglehawk. Miners walked to work and often worked night shifts. Living near work was essential. There were concentrations of miner housing in areas of successful mines. The districts of New Chum, Garden Gully, Ironbark and Victoria Reef were distinctive miner suburbs. Yet miners built where the mines were located and where auriferous Crown land was available. At St Just Point, miners built on Crown land both within the City of Sandhurst and the Shire of Marong. Unlike Melbourne, these were not orderly subdivisions created by developers, with terraces fronting onto streets. In many areas miners and their families walked along rough tracks, and houses were distributed in seemingly random ways. On Ironbark Hill cottages looked down the hill and often do not face the streets that were surveyed decades after the cottages were built. (See figures 1 and 2 for examples of miners’ cottages.)

Although holders of miner’s rights could occupy Crown land for residences, they had little security of tenure. Miner’s rights had to be renewed annually. They could also be resumed for mining, and holders could not leave the land unoccupied. In 1881 local Legislative Assembly members piloted through the first of a series of acts that essentially gave all the benefits of freehold. The Residence Areas Act 1881 was to be read as part of the Mining Statute of 1865 and came into operation on 1 April 1882. A residence area was defined as any Crown land not exceeding a quarter of an acre occupied ‘for the time being in accordance with the provisions of the Mining Statute by any holder of a miner’s right or a general business license’. The holder of a residence area had to have his block endorsed on the miner’s right document; this was registered annually by the Mines Department. Existing miner’s right landholders who had held their land for more than 12 months were granted all the rights and privileges of the new act. New holders of a miner’s right had to build a residence within four months. If no residence was erected after a further three months, the residence area could be cancelled. After 12 months the holder could let out the residence area with all the rights and privileges of normal landlords and tenants.

As unemployment rose in the 1880s the right to temporarily leave a residence area permitted miners to travel in search of work. They could also hold another residence area if it was not within 10 miles of an existing area. Although a residence area was exempt from occupation for mining under any miner’s right, the Governor in Council could temporarily exempt any portion of a district in which a new discovery of gold had been made. In such cases compensation had to be paid. After 12 months holders of a residence area could sell their interest in it. The new holder had to hold a miner’s right and have the residence area endorsed by the Mines Department on their right. Having the residence area endorsed annually was required by all holders, and failure to do this could result in loss the land.

Clause 21 of the Residence Areas Act 1881 legislated for conversion of Crown land to freehold by auction at an upset price to be determined by the Governor in Council. The Residence Areas Act 1884 amended the sale provisions to remove the competitive aspect of auction. Those who had held a residence area for two and a half years were given exclusive right of purchase if there were no objections to alienation on the grounds that the land was auriferous or required for other purposes. The value of the land was to be approved by an appraiser nominated by the Board of Land and Works, and the holder was to receive a valuation for improvements if the Crown required the land. This same act increased the area available from one quarter of an acre to one acre. These provisions were incorporated into the Mines Act 1890, and the right of existing holders not to have their residence areas negated by mining officials was legislated in an amendment to the Mines Act 1892. The Mines Act 1897 reduced the annual miner’s right fee to 2 shillings and 6 pence. The Residence Areas Holders Act 1910 permitted the transfer of residence areas to widows whose husband died intestate without a grant of probate if the area was valued at less than £250 and the total value of the estate was less than £250. This removed from poor widows the expensive legal costs of seeking probate. These laws enabled miners to make improvements to their dwellings.

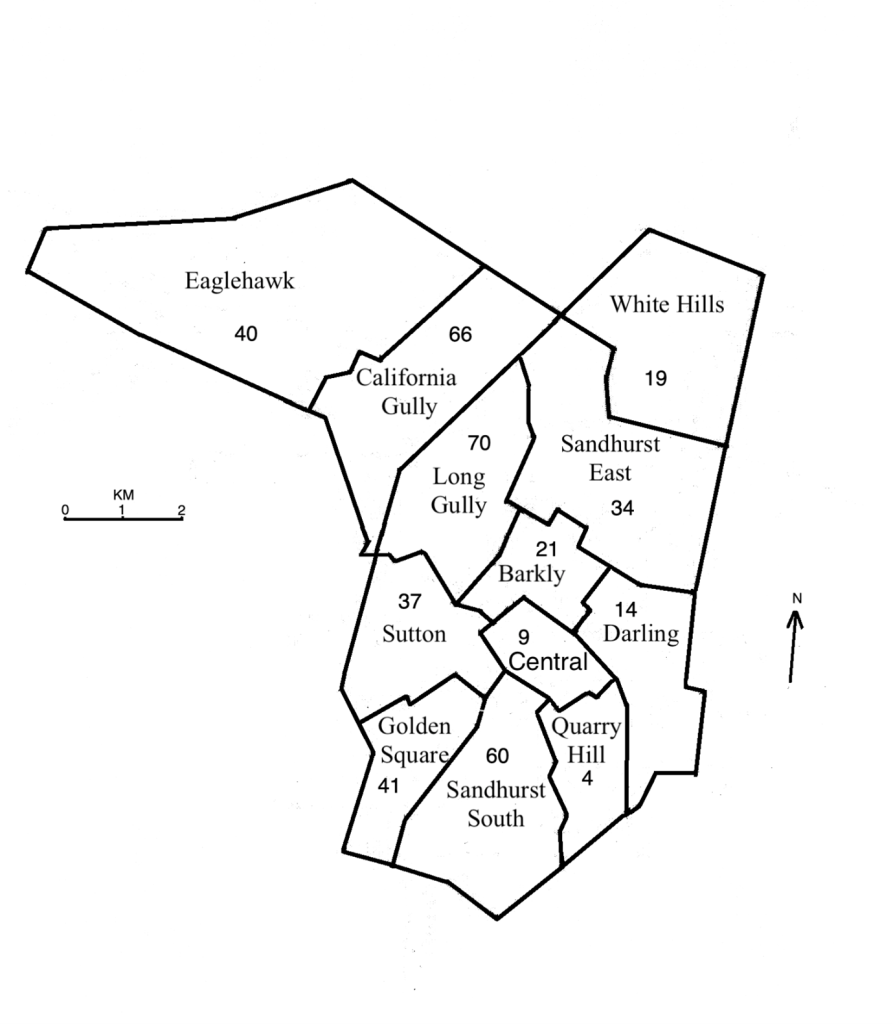

To explore the geography of Bendigo, I have divided it into the 12 electoral subdivisions used for the first federal electoral roll in 1903 (Map 2). In 1871 the proportion of houses occupied on a miner’s right in Sandhurst (figures are not available for Eaglehawk) was 48 per cent; by 1891 the proportion was still 32 per cent. If we include Eaglehawk the proportion rises slightly to 35 per cent. While residence areas were located in all divisions in 1891, it was more common in the divisions with significant quartz mining operations: Sandhurst South, Golden Square, Sutton, Long Gully, California Gully and Eaglehawk. It was also significant in Sandhurst East, where brickworks and noxious industries were located (Map 2 ). Here residence areas were located on former alluvial mining land. By 1891, changes in the law broadened the diversity of the miner’s residence area holders beyond simply miners; miners occupied 58 per cent of residence areas, while other manual workers – skilled and unskilled – occupied just over a third. The remaining residence areas were spread among the other occupational groups. Women became important holders of Crown land through the death of their husbands. The extension of available areas from a quarter of an acre to one acre enabled families to grow vegetables and fruit and raise poultry. This was important as unemployment rose in the late 19th century. Widows could use this increased area to run small dairies.

The miner’s right and later the miner’s residence area was a potent sign of the freedoms offered in the new world of Victoria. In 1856, holders of miner’s rights could vote for the recently constituted Parliament of Victoria. The first parliament enacted adult manhood suffrage (female suffrage had to wait). For over 50 years thousands of men on the goldfields were automatically placed on the electoral roll by virtue of their appearance on local government rates books as holders of a miner’s right or residence area. A more cherished freedom may have been the simple fact that goldfields residents could be free of landlords, living in houses they had built, or partially built, with ample gardens. The miner’s cottage was a seminal point in the development of the Australian dream of home-ownership. Yet despite this historical importance, early heritage investigations failed to protect the miner’s cottage.

- Bendigo was awarded municipal status as Sandhurst in 1855. It was proclaimed a borough in 1863 and a city in 1871. Eaglehawk was gazetted as a borough in 1862. ↵

- See Geoffrey Serle, The Golden Age: A History of the Colony of Victoria, 1851–1861 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1963). For the early history of Bendigo see Frank Cusack, Bendigo: A History (Melbourne: William Heinemann, 1973). The Bendigo Goldfield was resumed from the Mt Alexander No. 2 Ravenswood pastoral run. ↵

- This history of the miner’s cottage is drawn from Jane Amanda Jean and Charles Fahey, The Evolution of Housing on the Bendigo Goldfields: A Case for Serial Listings (City of Greater Bendigo, 2020): 38–39. The city provides PDFs of their heritage studies since 1993. Contact strategic.planning@bendigo.vic.gov.au. For an excellent overview of the miner’s cottage generally see Tony Dingle, “Miners’ Cottages,” Australian Economic History Review, 50, no. 2 (July 2010): 162–177. For life in a Bendigo mining community see Charles Fahey, “Happy Valley Road and the Victoria Hill District: A Microhistory of a Victoria Gold-Mining Community”. ↵

- For labour conditions in the gold mines see Charles Fahey, “Labour and Trade Unionism in Victorian Goldmining: Bendigo, 1861–1915’ in Gold: Forgotten Histories and Lost Objects of Australia, eds Iain McCalman, Alexander Cook and Andrew Reeves (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001). ↵

- For the traditional practices of home building in Cornwall see Damaris Rose, “Home Ownership, Subsistence and Historical Change: The Mining District of West Cornwall in the Late Nineteenth Century,” in Class and Space: The Making of Urban Society, eds Nigel Thrift and Peter Williams (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1987), 108–153. ↵