10.1 Early 20th Century Calls by First Nations Activists for “Voice” within Australia’s Parliamentary Institutions

Madeleine Gome

Content Note: This article contains images of Aboriginal people who have died. It includes offensive language when quoting from historical sources.

Read Madeleine Gome’s Wikipedia entry.

***

Aboriginal Voice to Parliament (1900-1950)

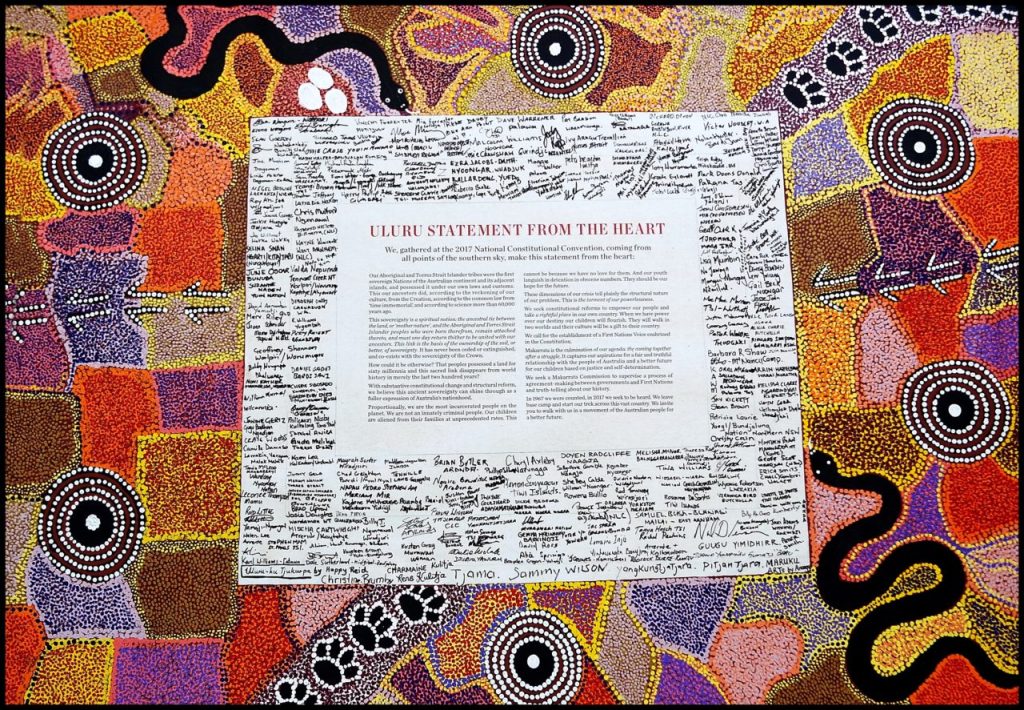

The Voice to Parliament is a proposal to establish a body of Aboriginal peoples to advise the Australian Government on matters concerning Aboriginal people and issues. In 2017, the Uluru Statement from the Heart and Referendum Council Final Report called for the implementation of a new representative body. The concept of Indigenous representation in Parliament is not new. Aboriginal activists have sought such action since the early 20th Century.

Background

Activism by Aboriginal people has occurred since Britain first settled Australia.[1] The first politically active Aboriginal organisation was established under the leadership of Fred Maynard in 1924.[2] Other bodies such as the Australian Aborigines’ League and Aboriginal Progressive Association soon followed.Indigenous activism in the 1920s and 1930s centred on the need for Aboriginal affairs to be federally administered, and opposition to the oppressive powers of state Protection Boards which implemented policies of child removal and dispossession of land.[3] Activists such as Bill Ferguson, Faith Bandler, Jack Patten, Pearl Gibbs and William Cooper campaigned for equal citizenship rights.Many Aboriginal leaders of the early 1900s also sought an Indigenous voice to parliament. While the Uluru Statement from the Heart has reignited public debate about a representative body, the proposal stems from a hundred-year history. Although the exact form and functions of such representation differed between activists and across time, the consistent message has been a call for empowerment and self-determination of Aboriginal affairs.[4]

1920s

Fred Maynard

Maynard was a Worimi man who founded the first Aboriginal political activist organisation, the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA), in 1924. The group’s activism focused on the forced removal of Aboriginal people from reserve land in New South Wales, and the removal of Aboriginal children from their families by the New South Wales Aboriginal Protection Board. The organisation also led the call for Indigenous people to have determination over Aboriginal Affairs.[5] In 1927 Maynard stated:[6]

Our request to supervise our own affairs is no innovation. The Catholic people in our country possess the right to control their own schools and homes, and take pride in the fact that they possess this privilege. The Chinese, Greeks, Jews and Lutherans are similarly favoured and our people are entitled to precisely the same conditions

–Fred Maynard, Letter to the Premier, 1927

1930s

Shadrach James

Shadrach Livingstone James was a Yorta Yorta man, the son of renowned teacher and activist Thomas Shadrach James. He was a law student, lobbyist, legal advisor, activist and central figure of the Aborigines Progressive Association of Victoria. James was a prolific campaigner, renowned for his remarkable handwriting.[7] In one 1930 article written for the Herald, James proposed ‘a native representative in Federal Parliament’.[8] This is the first known example of an Australian newspaper publishing a call for Aboriginal parliamentary representation.

William Cooper

Yorta Yorta Elder William Cooper established the Australian Aborigines’ League (AAL) in 1934.[9] The organisation called for an end to all forms of discrimination against Aboriginal people. One of the AAL’s main demands was for parliamentary representation.[10] In 1932 Cooper began seeking signatures for a petition to the King requesting intervention for the betterment of Aboriginal people. He spent six years circulating the petition across Australia.

The finalised petition, presented to the government in 1937, held nearly 2,000 signatures.[11] It asked that Aboriginal people be granted ‘representation in the Federal Parliament’ by ‘one of our own blood’ or by a white person ‘known to have studied our needs and to be in sympathy with our race’.[12] The government under Prime Minister Lyons never sent the petition to the King. In 2014, Cooper’s grandson Uncle Alf “Boydie” Turner facilitated its presentation to Queen Elizabeth.[13]

Joe Anderson

King Burraga (Joe Anderson) was a Dharawal man who lived along the Salt Pan Creek in New South Wales. Because his parents owned the land on which the family lived, it was an area not controlled by the Protection Board. The ‘Salt Pan Camp’ became a haven for those seeking to escape government control. King Burraga was one of the first Aboriginal people to use film as part of his activism.[14] In 1933 he told a Cinesound production that ‘all the black man wants is representation in Federal Parliament.’[15]

1940s

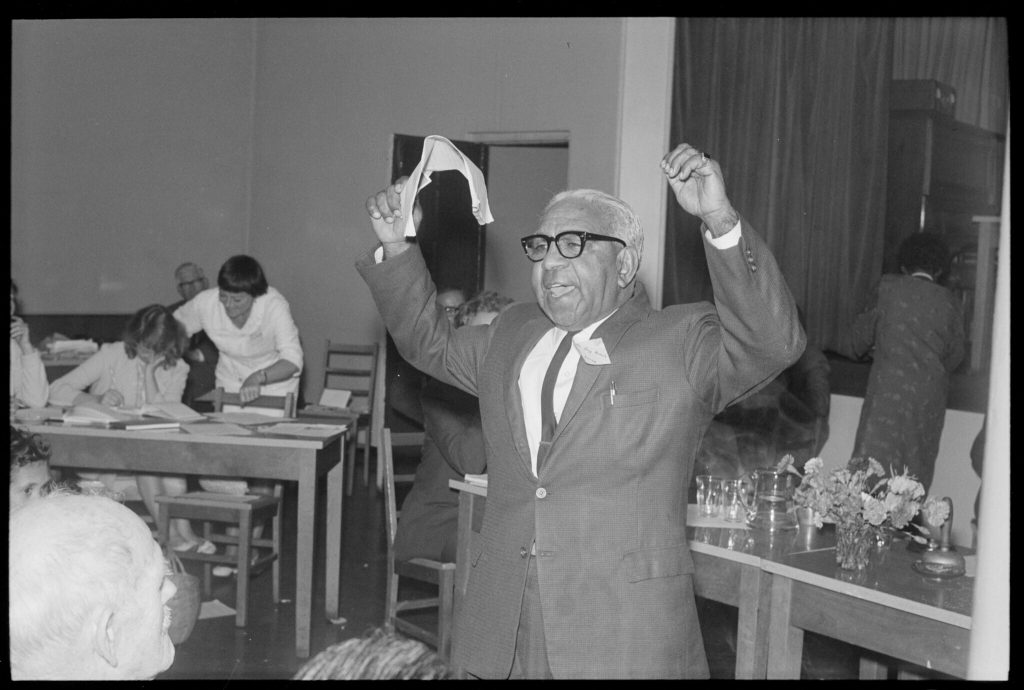

Sir Douglas Nicholls

Yorta Yorta man Sir Doug Nicholls was a beloved footballer, soldier, pastor, and activist.[16] As a mentee of William Cooper, Nicholls was a central figure of the Australian Aborigines’ League in Victoria. He was closely engaged in contemporary activism such as the Day of Mourning and the 1967 Referendum campaign. Nicholls went on to be a founding member of the Victorian Aborigines’ Advancement League and the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.[17]

On 1 July 1949 Nicholls wrote to Prime Minister Chiefly seeking parliamentary representation of Aboriginal people and outlining how such a process might work:[18]

I write to ask your support on behalf of my fellow members of the Australian Aboriginal race for our request that we be accorded representation in the Australian National Parliament.

The request is that provision should be made for the election to the House of Representatives of a representative of the Australian Aboriginal race to be elected upon the vote of all aborigines enrolled under the current Commonwealth franchise…

We feel that we are not asking more than the minimum to which we are entitled in requesting one spokesman for the native Australian race to sit in the Australian National Parliament.

–Sir Douglas Nicholls, Letter to the Prime Minister, 1 July 1949

While there have been Indigenous parliamentarians and Ministers for Aboriginal Affairs since the time of writing, there remains no person or body elected by Aboriginal voters for the purpose of representing Aboriginal interests.

Progress

From the late 1950s onwards, the focus of Aboriginal activism shifted to land rights. Key examples of such activism include the Yirrkala Bark Petitions and the campaign leading to the Mabo decision.

Multiple Aboriginal representative bodies have been established and subsequently disbanded, including the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCATSI) and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC).

The Voice proposed by the Uluru Statement from the Heart was initially rejected by the Turnbull Government. In 2019 the Morrison Government initiated a co-design process with the formation of a Senior Advisory Committee co-chaired by Marcia Langton and Tom Calma. The Committee’s work is ongoing.

See also

Reflection

I produced my Making History project on unceded Wurundjeri land. My Wikipedia-style article provides an overview of calls by First Nations activists for representation in the first half of the 20th Century. The purpose of my article was to contextualise public debate surrounding the introduction of a Constitutionally enshrined First Nations Voice to Parliament. This national conversation was sparked following the release of the Uluru Statement from the Heart in 2017, and heightened after the election of the Albanese government in mid-2022.

Having previously read Professor John Maynard’s work, I knew there is a relative scarcity of academic writing on First Nations’ activism in the early 20th Century, and what has been written is often kept behind a paywall. I chose to write a Wikipedia-style article because this format is synonymous with succinct, easily understandable information. Given there was no Wikipedia page dedicated to the topic, this was the appropriate format because it aligns with Wikipedia’s requirement that information shared on the website be “noteworthy”.

The main challenge I faced was scrutinising the concept of “reliable” and “authoritative” sources. At university the bastion of reliability is the peer reviewed academic journal. While I could find such content on some key figures such as Uncle William Cooper, there was little or no academic literature on other activists. This challenged me to closely examine my perspective on what constitutes “relatable” information. Ultimately I chose to include sources which were produced by or drew from the knowledge of First Nations people directly, even if the information was presented in a less formally academic format, such as a website.

I had to make editorial and ethical decisions about language. Firstly, I struggled to adopt the “neutral” language required by Wikipedia. To align with this policy I chose to use language such as “child removal“ instead of “forcibly removed” or “stolen”. Secondly, I decided to include out-dated language when quoting directly from First Nations activists. However, I included a content note so readers who did not feel comfortable with this type of language could choose to avoid it. I also placed a content note at the beginning of my article warning that the article contained images of First Nations people who have died. The simplest but most impactful ethical and editorial decision I made was to ensure that the majority of my sources were by First Nations authors.

January 2023, Philippines

- Maynard, John (1997). “Fred Maynard and the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA): One God, One Aim, One Destiny”. Aboriginal History. 21: 1. ↵

- Maynard, John (2003). “Vision, Voice and Influence: The Rise of the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association”. Australian Historical Studies. 34 (121): 91. ↵

- Maynard, John (1997). “Fred Maynard and the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA): One God, One Aim, One Destiny”. Aboriginal History. 21: 1-13. ↵

- Davis, Megan; Langton, Marcia (2016). It's Our Country: Indigenous Arguments for Meaningful Constitutional Recognition and Reform. ↵

- Maynard, John (1997). “Fred Maynard and the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA): One God, One Aim, One Destiny”. Aboriginal History. 21: 1-3. ↵

- Maynard, Fred, 1927, [Letter to the Premier], NSW Premiers Department Correspondence Files, A27/915 in Maynard, John (1997). “Fred Maynard and the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA): One God, One Aim, One Destiny”. Aboriginal History. 21: 9. ↵

- ‘Shadrach Livingstone James’ (2021). First Peoples Relations [website] https://www.firstpeoplesrelations.vic.gov.au/shadrach-livingstone-james. Accessed 28 April 2022. ↵

- James, Shadrach L. (24-03-1930). “Help my People!”. Herald. In Attwood, Bain; Markus, Andrew (1990). The Struggle for Aboriginal Rights: A Documentary History. ↵

- Darian-Smith, Eve (2013). Review of Barbara Miller, William Cooper Gentle Warrior: Standing Up for Australian Aborigines and Persecuted Jews. Aboriginal History. 37: 193; Foster, Robert (2018). “Contested Destinies: Aboriginal Advocacy in South Australia’s Interwar Years”. Aboriginal History, 42: 73. ↵

- Markus, Andrew (1983). “William Cooper and the 1937 Petition to the King”. Aboriginal History. 7 (1): 48, 55. ↵

- Markus, Andrew (1988). Blood From a Stone: William Cooper and the Australian Aborigines’ League; Thorpe Clark, Mavis (1965). Pastor Doug: The Story of an Aboriginal Leader. ↵

- Cooper, William (15-10-1933). “Petition to the King”. Herald. In Attwood, Bain; and Markus, Andrew (1990). The Struggle for Aboriginal Rights: A Documentary History. ↵

- Jacks, Timna (4-10-14). “Queen Accepts Petition for Aboriginal Rights, 80 Years on”. Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2022-04-29. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/queen-accepts-petition-for-aboriginal-rights-80-years-on-20141003-10ksh6.html. ↵

- ‘The Burraga Story’, The Burraga Foundation [website]. Retrieved 2022-04-28. https://www.burraga.org/about. ↵

- NITV (2017). “King Burraga”. Facebook [website]. Retrieved 2022-04-29. https://www.facebook.com/NITVAustralia/videos/10154771387477005/. ↵

- Thorpe Clark, Mavis (1965). Pastor Doug: The Story of an Aboriginal Leader. ↵

- Broome, Richard. (2012). Australian Dictionary of Biography: Nicholls, Sir Douglas Ralph (Doug) (1906-1988). Retrieved 2022-04-29. https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/nicholls-sir-douglas-ralph-doug-14920. ↵

- Nicholls, Doug (1949-07-01). Letter to Prime Minister Chifley, R Menzies and A Fadden. In Attwood, Bain; Markus, Andrew (1999). The Struggle for Aboriginal Rights: A Documentary History. ↵