8.1 James “Jim” Edwin Wiggins: Surviving the Second World War

Thomas Amos

The Second World War was one of the significant periods in Australia’s history, as its victory brought a rapid period of economic prosperity and a more independent outlook.[1] However, over 30,000 Australians would become prisoners of war.[2] This essay will discuss the wartime experience of one of these prisoners, my great-great-grandfather James (‘Jim’) Edwin Wiggins. Many of his stories can be told through the items he brought home. These items have remained in the family for over four generations, alongside the stories which make them significant. Therefore, this essay will give a more detailed background and metadata to the stories and the items which make Jim’s wartime experience. After struggling to find a stable job during the Great Depression, Jim would enlist to serve his country and receive a chance of regular employment. Jim would be part of the Battle of Singapore, where he became a Japanese prisoner of war (‘POW’) and spent a year in Changi. After consistent sickness in Changi, Jim would become part of “G Force” and was sent to Japan. He would spend the rest of the Second World War in Osaka and Takefu. After coming home, Jim would never fully come to terms with this experience.

The stories that make up this essay are a product of an inherited legacy, as I become the third generation in my family to write about them.

Many of these stories were saved by my great-grandmother, Jessie Cameron (nee Wiggins), who received them through her brother.[3] Jim would usually only discuss his wartime experiences with his male friends and sons.[4] Thus, this was a clear rejection of Jim seeking control over his story and the transmission of social emotions to his family.[5] Moreover, the items behind Jim’s wartime experience would fall into what Buchanan calls “ambient knowledge”.[6] While some of the items can highlight the shared experiences of Japanese POWs, most of them are constructed through Jim’s experience and family knowledge. Moreover, all of Jim’s items have precise metadata that I have encountered.[7] The metadata collected in the past has mainly been related to Jim’s stories and how they survived. The role I play with this essay is to create better metadata by adding thicker, academic-based descriptions to Jim’s item and his story.[8] Therefore, this metadata can provide a more accurate foundation for future research projects into Jim’s life.[9]

On 18 January 1903, Jim was born on his parent’s farm in Korong Vale.[10] Soon after, they moved to the small farming district of Emu, near Bealiba.[11] He would continue to live in Emu until 1927 when he and his young family moved to Maffra.[12] During his time working as a seasonal lumberjack in Gippsland, he and his family would feel the impacts of the Great Depression.[13] For example, his family lived mainly off the vegetables he grew with occasional rabbit and fish.[14] They would move to Shepparton in 1935, living in a two-roomed tent.[15] Jim would work as a fruit picker and channel digging on sustenance.[16] They would move back to St. Arnaud in 1936, but Jim’s struggle to find work continued.[17] Jim would enlist in the Australia Imperial Force (‘AIF’) on 28 June 1940.[18] There were two main reasons why Jim enlisted: he thought it was the right thing to do for Australia, and he wanted a chance at stable employment.[19] The “king and country” sentiment was common in mid-1940, as the Battle of Britain was beginning.[20] The highest peak of AIF enlistment occurred during this time.[21] Moreover, Jessie also noted that “six shillings and day and … [a family] allowance” got many men to enlist.[22]

However, Jim would not fit the “average Australian soldier” aged in his 20s from an industrial or white-collar background described by Grant and James.[23] He was 37 and from a rural background with five children.

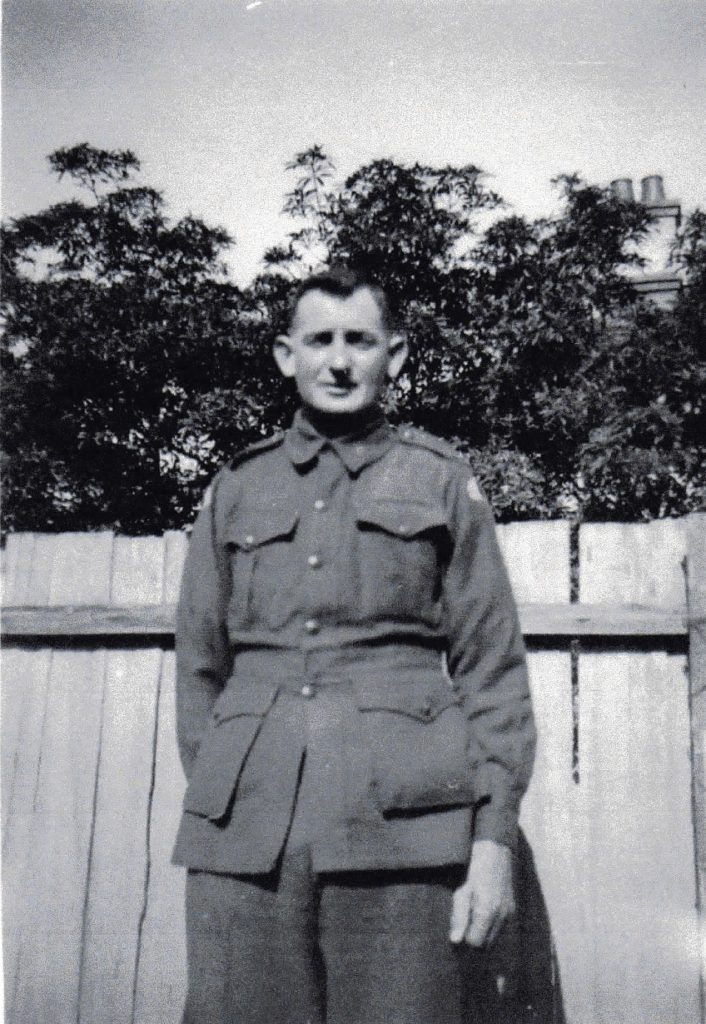

Figure 2 is Jim’s last photo with his children before going overseas. Jessie Cameron hated this photo because it shows her and her siblings’ “sad faces”.[24]

Jim would sail from Fremantle on 8 August 1941, arriving in Singapore a week later.[25] Jim was a member of the 2/29 Battalion, and their first barracks were in the suburb of Katong.[26] Soon after, he would be hospitalised with mumps.[27] After being discharged, he joined the 27th Brigade because the 2/29 had moved into British Malaya.[28] Jim would spend the next three months in the Johore state of British Malaya, participating in the Malayan Campaign.[29] In January, the 27th Bridge would take part in the Battle of Singapore.[30] The fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942 would have significant adverse effects on Australia, as the war would come closer to home. For Jim, the British surrender would mean he would become one of the 22,000 Australians to become Japanese POWs between January and March 1942.[31]

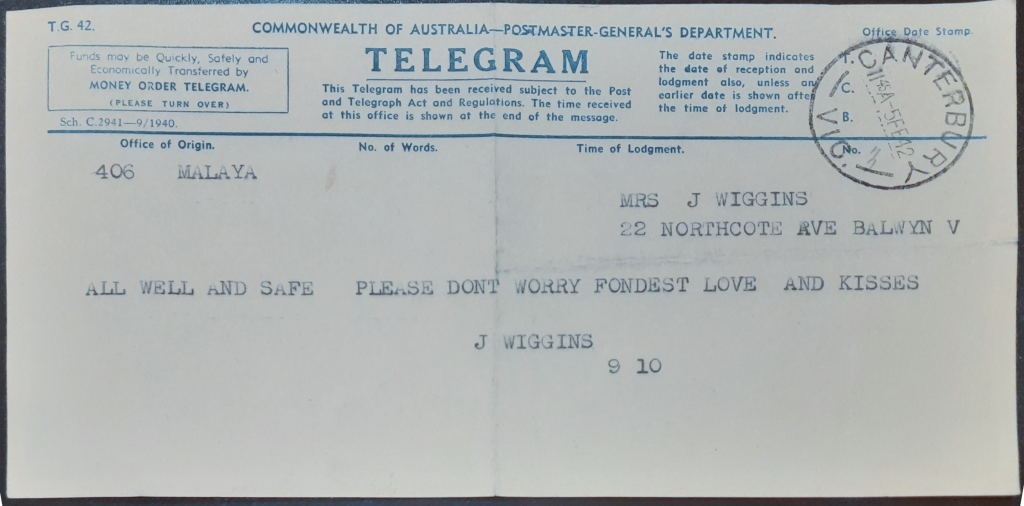

Figure 3 is Jim’s last form of communication with his family before becoming a Japanese POW. The next time Jim’s family would hear from him was around six months later.

Furthermore, Jim would be marched to the Changi POW Prison two days later.[32] It would serve as a transit camp where prisoners were housed until being moved on as forced labours in Burma, Borneo, and Japan.[33] Hygiene and sanitation would become a massive concern in Changi. Tropical diseases would be a constant threat due to Singapore’s climate, causing malaria and cholera outbreaks.[34] Jim would suffer dysentery and Dengue fever during his time in Changi, and his weight would also drop from 76kg to 38kg.[35] Many of the items Jim kept during his wartime experience tell us about his time in Changi:

Figure 4 shows the spoon he would eat rice with throughout his wartime experience. POWs would struggle with a severe lack of food and malnutrition caused by an imbalance, rice-based diet.[36] Small groups of prisoners would scrounge food and share it, as rice rations were too small and left POWs hungry.[37]

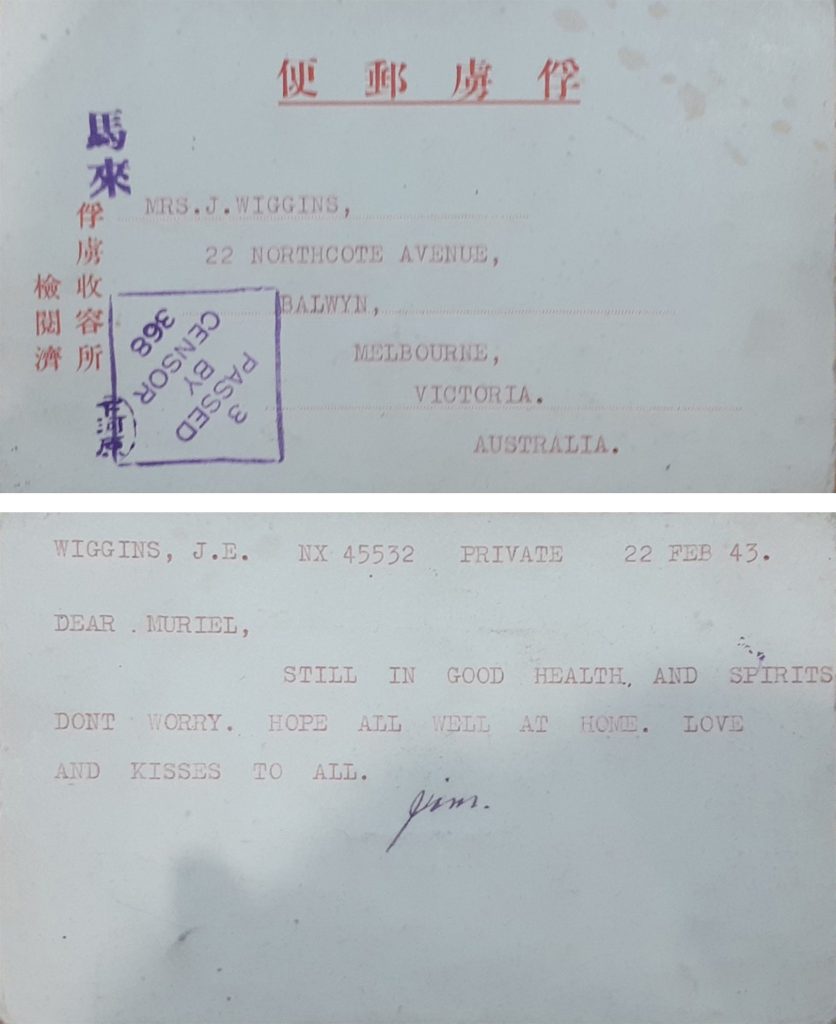

Figure 5 shows one of the postcards he sent home to his family from Changi. The postcards were strictly restricted to only 24 words, and the Japanese gave detailed instructions on what the POWs could and could not write. However, the response from the POWs was highly positive as the need for communication with home was long desired.[38]

In 1943, Edward “Weary” Dunlop decided Jim would be sent to Japan as a cooler climate may give him a better chance of survival.[39]

This most likely occurred in January when Dunlop was organising his forces who would become forced labourers on the Burma-Thailand Railroad.[40] Thus, Jim would become part of “G Force”, who would be sent to Japan on 25 April 1943.[41] Many G Force POWs were mainly sick, disabled, or hospital and maintenance staff.[42] G Force would be transported to Japan on a one-month voyage on a “hell-ship”.[43] Onboard these ships, POWs were forced into overcrowded holds and suffered further severe malnutrition and disease due to starvation, dehydration, and inadequate hygiene.[44] The hell-ships would also be where many POWs first interacted with Japanese soldiers, as Australian and British officers were still responsible for enforcing discipline in Changi.[45] Jim’s movement over the next two years is based on primary sources. Jim would be stationed at the Taisho POW camp in Osaka.[46] He most likely worked in the Osaka Ironworks until March 1944, when he became too weak to walk.[47] He then began working around the camp, repairing boots for Japanese officers and gardening.[48]

-

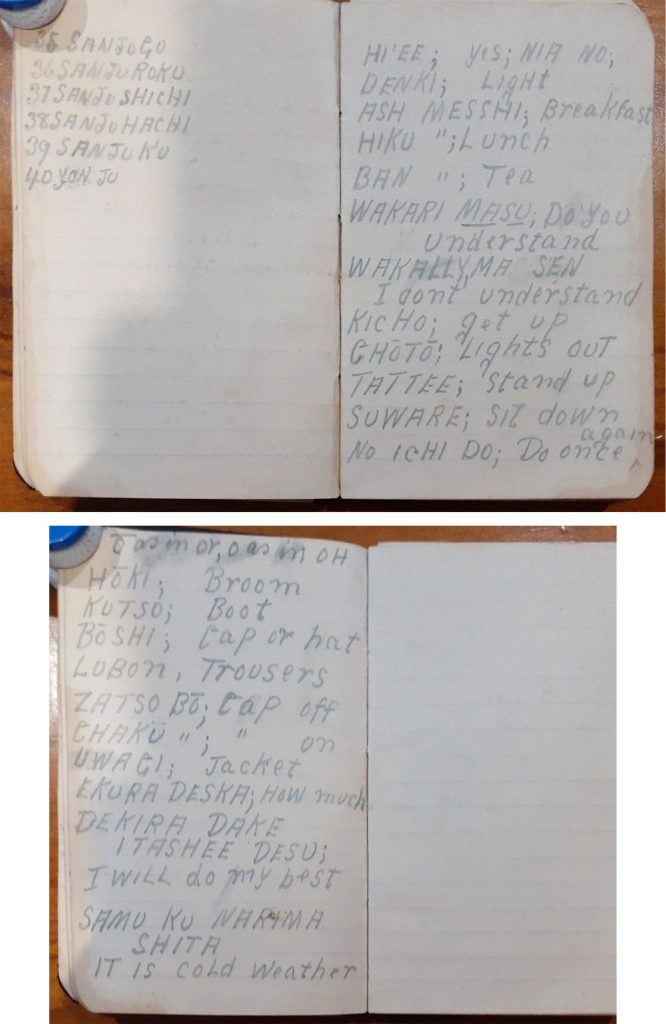

Figure 6: Pages from Jim’s service book showing Japanese transitions. Source: VX45532 James Edwin Wiggins AIF Service Book [notebook] (c. 1940-1945). Used under CC-BY-NC-ND.

Figure 6 shows Japanese translations of commands from his service book. The Japanese saw to reinforce the POW position during their inactions, seeing its use as enforcing the Imperial Japanese Army (“IJA”) wishes.[49]

However, the conditions of POW camps in Japan would vary significantly.[50] Jim did have his thumbs flattened with a hammer once by an IJA guard and had lash marks on his back from beating.[51] The POWs received three small bowls of rice each day in Taisho.[52] Jim would steal small pumpkins from the garden when working in the camp.[53] He also climbed a wall from his boot-mending hut, across the ceiling of the guard’s room, to scrounge rice from the connected storeroom.[54] Although only approximately four Australian POWs died as members of G Force, many were still very sick.[55] POWs were marched to and from the Ironworks each day, around 2.4km from the camp.[56] They would work 10-hour shifts, having a rest day every two weeks.[57] When Jim became too weak to walk, he had to be supported by the workers and guards back to the camp.[58] Moreover, Jim recorded interactions with Japanese civilians were positive, holding no hatred towards them.[59] One of Jim’s stories was about an older man putting a newspaper in the wire of the prison fence each day.[60]

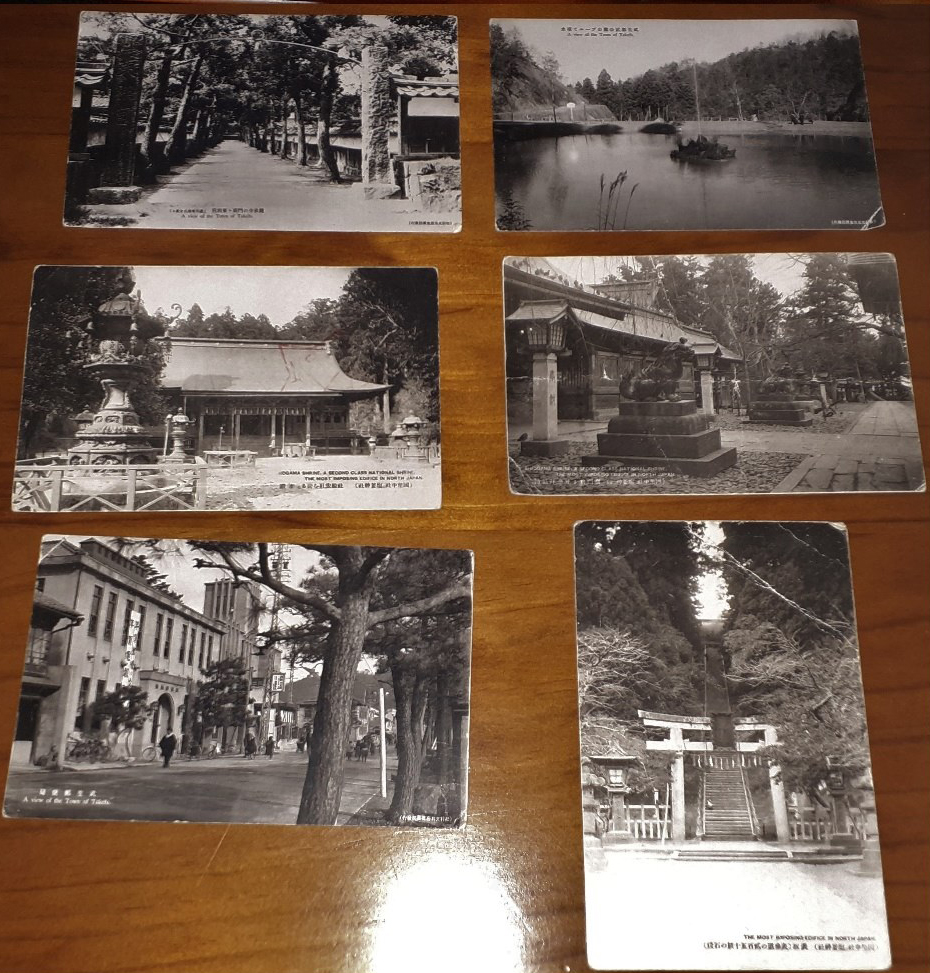

By May 1945, Jim was moved to Takefu POW camp, like many of the prisoners in Taisho.[61] Part of the reason prisoners speculated for this move was that Osaka had been becoming a target of American bombing raids.[62] On 15 August 1945, Japan surrendered to the Allies, ending the war.[63] Jim’s activities after leaving the camp are not entirely known, but he was in Yokohama in early September before travelling to Manilla.[64] However, several of Jim’s items do tell stories from this time:

Figure 7 shows scarves made out of parachute silk and figure 8 shows a collection of postcards from Takefu. The postcards were picked up as souvenirs when he was allowed out of the camp. The parachute silk scarves were in American food supply drops, which started on 28 August.[65] These supplies allowed Jim to gain 12kg within the first month since the ending of the war and were also regularly shared with Japanese civilians.[66]

Figure 9 shows another souvenir Jim got in Japan, a doll. The story surrounding this was one of Jim’s friends, who was too weak to go out, started crying when he saw it because he could not get any souvenirs.[67] Therefore, Jim decided to give him the dog connected to the doll.[68]

Additionally, Jim was discharged from the AIF on 3 December 1945, returning to Australia on the HMS Formidable.[69] Jim had regained his weight to 88kg by the time he returned.[70] When receiving food on the HMS Formidable, he would jump back in line to receive seconds.[71] After the war, Jim worked with his sons in Melbourne for Victorian Railways before moving back to St. Arnaud.[72] Like many, Jim would feel the effects of wartime experience for the rest of his life. One incident was when multiple planes were surveying over St. Arnaud; Jim had nightmares and would go to the ground when they flew over.[73] This suggests he was suffering some form of trauma, which the development of its understanding would occur over the post-war years.[74] Jim rarely talked about his wartime experience, only talking about them to his friends and sons.[75]

Jim died on 8 December 1967 at the age of 64 from heart failure.[76] Thus, he would not live to see the significant developments towards the attitudes of former POWs. Firstly, there was growing international attention toward previous human rights violations starting from the 1970s.[77] And secondly, post-traumatic stress disorder was officially recognised as a psychiatric category in 1980.[78]

To conclude, my great-great-grandfather, James (“Jim”) Edwin Wiggins, was one of the many Australians that became a Japanese prisoner of war during the Second World War. His items and stories from his wartime experience have been passed down through four generations of my family. This essay gives some more described context and metadata so that future projects can have a more accurate foundation into Jim’s life. Like many, Jim struggle to find stable employment during the Great Depression. Enlisting gave Jim a chance at regular employment and allowed him to support his country. He fought in British Malaya and Singapore before being captured as a POW after the fall of Singapore. Jim would spend a year in Changi and suffer sickness and serve malnutrition. In 1943, he was sent to Japan on a hell ship as part of G Force. Jim would spend the rest of his wartime experience in Osaka and Takefu. He would work in factories before becoming so weak that he could not walk without support. Jim would come home and resume his ordinary life but would feel the effects of his wartime experience for the rest of his life. Unfortunately, he died before many realised the struggles Japanese POWs faced when returning home.

Reflection

My essay discussed my great-great-grandfather, James (‘Jim’) Edwin Wiggins, experience as a Japanese Prisoner of War (POW) during the Second World War. This essay is structured around items kept from his experience, such as letters and photographs, letting their stories produce scholarly analysis. Using Rachel Buchanan’s article, The Iran Album (1974): Some Sleeve Notes, as the template, the essay gives more detailed metadata to these items to show how archival material can be used in writing family or personal history. In this context, the metadata produced by my essay is academically based, adding to the existing family’s knowledge of Jim’s experience. That article became my primary influence because the initial idea was to use this project to show off these items while also telling Jim’s story.

The critical concept of Jim’s story is survival. Jim suffered severe sickness and hunger while interned as a Japanese POW. The survival concept is also relevant to the items. Many of their stories would not have survived if my great-grandmother, Jessie Cameron, had not saved them from Jim’s social control of his emotions. I also wanted to challenge Australian Second World War historiography. The average Australian Second World War soldier is often seen as a man in their 20s from an industrial, urban background. However, Jim does not fit this mould. He was 37 at the time of his enlistment and came from a rural background. I saw Jim’s story as a unique perspective from one of more than 30,000 Australians who found themselves Japanese POWs.

I chose the illustrated essay format because it was the best format to explain Jim’s life story, compared to a museum display. Although, I found it hard initially to give the essay’s narrative over the items because there were many other topics I wanted to discuss. For me, the hardest to leave out of the final version was his experiences from the Great Depression, which also connected to the survival concept very well. I also found it hard to reflect on the historian’s role fully. I understood I was adding academic-based information to stories recorded as personal accounts. However, I could not figure out how to express this aim within the essay. I realised afterwards this essay was an excellent example of the academic-based transformation family history has seen. This is because I used the material made by Jesse and Nan (Jan Amos) in a hobby-based pursuit and added academic research.

As gatekeepers of history, we intentionally make political editorial decisions whenever we discuss wars, mostly without realising. During this project, I did make clear political editing decisions. I wanted to avoid any sensitivity as the relationship between Australia and Japan has changed significantly since the end of the Second World War. I relied heavily on the notes Jessie wrote about the items, which focused on stories of torture and war crimes performed by the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA). The only stories of this nature which made it into the final essay were those I could back up with references from other primary accounts from Jim’s battalion and work parties. I also wanted to reinforce that Jim did not hold any hatred towards the Japanese, as many fellow POWs did, for the crimes committed against them by the IJA.

- Lachlan Grant and Karl James, ‘Australia and the Second World War’ in Paul R. Bartop (ed.), The Routledge History of the Second World War (Oxford: Routledge, 2021), 408. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Dorothy Patton and Mervynne Dunstan, ‘Interview with Mrs. Jessie Cameron’ in Dorothy Patton and Mervynne Dunstan (eds.), A Harvest of Memories: Oral History of Kara Kara District (St. Arnaud: Kara Kara Bicentennial Community Committee, 1988), 53. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ashley Barnwell, ‘Family Secrets and the Slow Violence of Social Stigma’, Sociology, 53/6 (2019), 1120. ↵

- Rachel Buchanan, 'The Iran Album (1974): Some Sleeve Notes', Archivaria, 85 (2018), 132. ↵

- Ibid. 129. ↵

- Ibid. 133. ↵

- Ibid. 128. ↵

- Victorian Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Birth 4196/1903. ↵

- Isabel Wardley, ‘Recollections of Isabel Wardley (nee Wiggins)’, in Dorothy Patton and Mervynne Dunstan (eds.), A Harvest of Memories: Oral History of Kara Kara District (St. Arnaud: Kara Kara Bicentennial Community Committee, 1988), 55. ↵

- Dorothy Patton and Mervynne Dunstan, ‘Interview with Mrs. Jessie Cameron’, 51. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. 52-53. ↵

- Ibid. 51. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. 52; John Lack and Peter Hosford (eds.), No Lost Battalion: An Oral History of the 2/29th Battalion AIF (McCrae: Slouch Hat Publications, 2005), 30. ↵

- Australian Army: Central Army Records Office, ‘VX45532 James Edwin Wiggins’ [letter to Jessie Cameron], 8 Sep. 1982. ↵

- Jan Amos, James Edwin Wiggins 1903-1967: My Grandfather [Compiled Notes] (c. 2010), 5; John Lack and Peter Hosford (eds.), No Lost Battalion, 30. ↵

- Ibid. 31. ↵

- Lachlan Grant and Karl James, ‘Australia and the Second World War’, 399. ↵

- Dorothy Patton and Mervynne Dunstan, ‘Interview with Mrs. Jessie Cameron’, 52. ↵

- Lachlan Grant and Karl James, ‘Australia and the Second World War’, 399. ↵

- Dorothy Patton and Mervynne Dunstan, ‘Interview with Mrs. Jessie Cameron’, 53; Jan Amos, James Edwin Wiggins 1903-1967: My Grandfather, 6. ↵

- VX45532 James Edwin Wiggins AIF Service Book [notebook] (c. 1940-1945). ↵

- John Lack and Peter Hosford (eds.), No Lost Battalion, 63. ↵

- VX45532 James Edwin Wiggins AIF Service Book [notebook] (c. 1940-1945). ↵

- Ibid; John Lack and Peter Hosford (eds.), No Lost Battalion, 63. ↵

- Joseph Morgan, 'A Burning Legacy: The 'Broken' 8th Division', Sabretache, 54/3 (2013), 6; John Lack and Peter Hosford (eds.), No Lost Battalion, 65. ↵

- Ibid. 12. ↵

- Ibid. 405. ↵

- VX45532 James Edwin Wiggins AIF Service Book [notebook] (c. 1940-1945). ↵

- R. P. W. Havers, Reassessing the Japanese Prisoner of War Experience: The Changi Prisoner of War Camp in Singapore, 1942-45 (Oxford: Routledge, 2003), 11; Lachlan Grant and Karl James, ‘Australia and the Second World War’, 405. ↵

- Lucy Robertson, ‘Changi: Military discipline in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp, 1942–45’, in Joan Beaumont, Lachlan Grant and Aaron Pegram (eds.), Beyond Surrender: Australian Prisoners of War in the Twentieth Century (Carlton: Melbourne University Press), 124. ↵

- VX45532 James Edwin Wiggins AIF Service Book [notebook] (c. 1940-1945); Jessie Cameron, VX45532 Private James Edwin Wiggins [Notes] (c. 1980s), 2. ↵

- R. P. W. Havers, Reassessing the Japanese Prisoner of War Experience, 43; Lucy Robertson, ‘Changi: Military discipline in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp’, 125. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- R. P. W. Havers, Reassessing the Japanese Prisoner of War Experience, 52-54. ↵

- Jessie Cameron, VX45532 Private James Edwin Wiggins, 2. ↵

- Sue Ebury, Weary: King of the River (Carlton: The Miegunyah Press, 2010), 195. ↵

- AWM54, 554/16/1, "G" Force (Japan): Reports on Taisho Sub Camp, Osaka - Oeyama Camp, Takefu camp. ↵

- Verdun Walsh, Cry Crucify (Ryde: Val Walsh & Associates, 1991), 139. ↵

- AWM54, 554/16/1; Cheah Wui Ling, 'Post-World War II British 'Hell-Ship' Trials in Singapore: Omissions and the Attribution of Responsibility', Journal of International Criminal Justice, 8/4 (2010), 1036. ↵

- Ibid. 1038. ↵

- Verdun Walsh, Cry Crucify, 139; Lucy Robertson, ‘Changi: Military discipline in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp’, 122. ↵

- AWM54, 554/16/1. ↵

- Ibid; James Wiggins, ‘Letter from Taisho POW Camp’ [letter to Muriel Wiggins and his children], 4 Jun. 1944. ↵

- Ibid; Jessie Cameron, VX45532 Private James Edwin Wiggins, 2. ↵

- R. P. W. Havers, Reassessing the Japanese Prisoner of War Experience, 59. ↵

- Lachlan Grant, ‘Breaking Barriers: The Diversity of Prisoner-Of-War Camps in Japan and Australian Contacts with Japanese Civilians’ in Joan Beaumont, Lachlan Grant and Aaron Pegram (eds.), Beyond Surrender: Australian Prisoners of War in the Twentieth Century (Carlton: Melbourne University Press), 167. ↵

- Jessie Cameron, VX45532 Private James Edwin Wiggins, 2; Jan Amos, James Edwin Wiggins 1903-1967: My Grandfather, 2. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Jessie Cameron, VX45532 Private James Edwin Wiggins, 2. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Verdun Walsh, Cry Crucify, 361-366; John Lack and Peter Hosford (eds.), No Lost Battalion, 180. ↵

- AWM54, 554/16/1. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Jessie Cameron, VX45532 Private James Edwin Wiggins, 2. ↵

- Ibid; Lachlan Grant, ‘Breaking Barriers’, 175. ↵

- Jessie Cameron, VX45532 Private James Edwin Wiggins, 2. ↵

- Verdun Walsh, Cry Crucify, 361. ↵

- Ibid; John Lack and Peter Hosford (eds.), No Lost Battalion, 180. ↵

- Lachlan Grant and Karl James, ‘Australia and the Second World War’, 408. ↵

- James Wiggins, ‘Letter from Manilla’ [letter to Muriel Wiggins], 10 Sep. 1945. ↵

- James Wiggins, ‘Letter from Manilla’ [letter to Muriel Wiggins], 10 Sep. 1945; Jan Amos, James Edwin Wiggins 1903-1967: My Grandfather, 17. ↵

- Ibid; Lachlan Grant, ‘Breaking Barriers’, 175. ↵

- Jessie Cameron, VX45532 Private James Edwin Wiggins, 3. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Australian Military Forces, 'Certificate of Discharge No. 311712: VX45532 Private James Edwin Wiggins', [certificate] (1945). ↵

- Dorothy Patton and Mervynne Dunstan, ‘Interview with Mrs. Jessie Cameron’, 52. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Jan Amos, James Edwin Wiggins 1903-1967: My Grandfather, 2. ↵

- Christina Twomey, The Battle Within: POWs in Post-War Australia (Sydney: NewSouth Publishing, 2018), 150. ↵

- Dorothy Patton and Mervynne Dunstan, ‘Interview with Mrs. Jessie Cameron’, 53. ↵

- Victorian Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Death 28106/1967. ↵

- Christina Twomey, ‘Compensating prisoners of war of Japan in post-war Australia’ Joan Beaumont, Lachlan Grant and Aaron Pegram (eds.), Beyond Surrender: Australian Prisoners of War in the Twentieth Century (Carlton: Melbourne University Press), 200. ↵

- [87] Ibid. ↵