Chapter 6: Schwerkolt Cottage: Local History, Public History, Conservation Heritage and the Past

David Harris

Introduction

Schwerkolt Cottage, at Mitcham in Melbourne’s eastern suburbs, is part of a heritage precinct that was created following a campaign between 1962 and 1965 involving the local community and the Nunawading municipal council. Initially promoted as an ‘original pioneer cottage’, the house and its surrounds are now also acknowledged as occupying Wurundjeri country. The house and the land have acquired further meanings that have enriched the site’s place in the area’s local history and more broadly in the history of heritage conservation in Victoria.

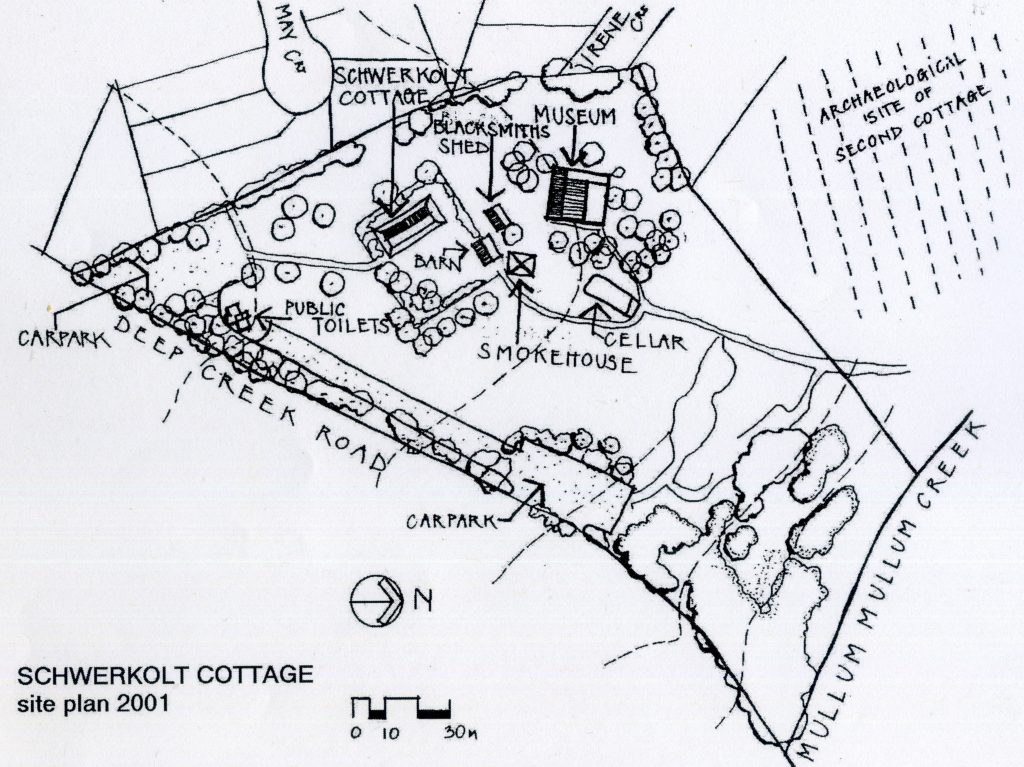

I first visited Schwerkolt Cottage in 2001, when I was the consultant historian on a project the Whitehorse City Council had commissioned to complete a conservation and management plan (CMP) on the Schwerkolt precinct.[1] Based on criteria used by heritage and collections management practitioners in Australia, the CMP was to establish the site’s cultural heritage significance. As part of the team, I contributed a chronology and an interpretative history of the site while cultural heritage consultant, Michele Summerton and heritage architect, David Wixted, addressed specific heritage requirements such as the conservation analysis and management plan, the identification of cultural significance, comparative cultural assessments, a museum environment assessment and the production of architectural drawings.

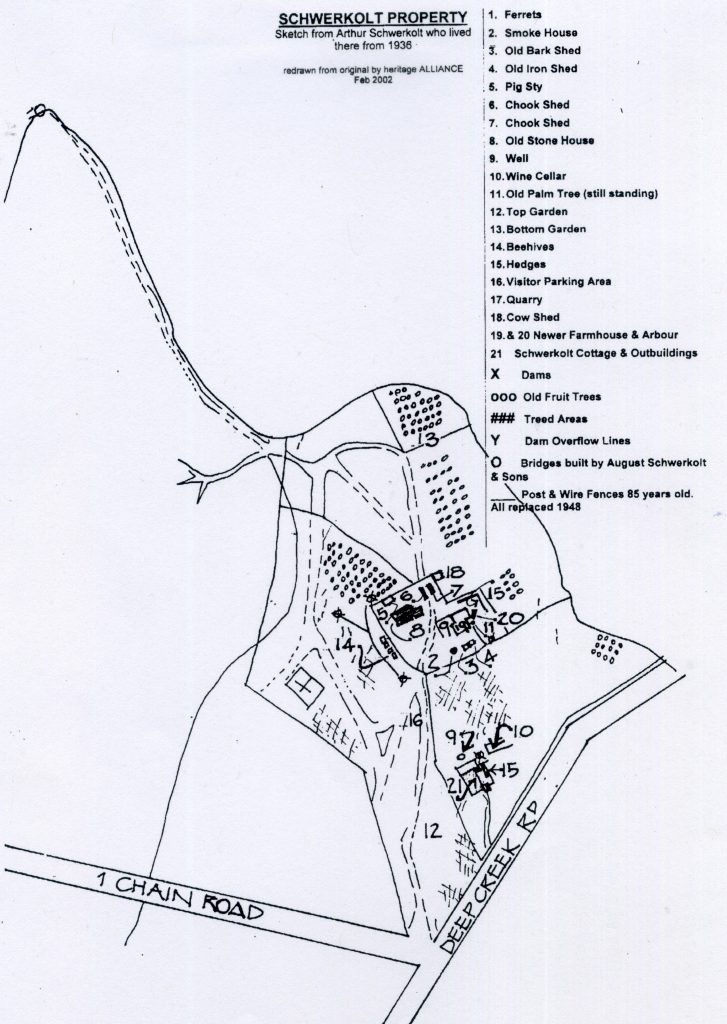

The Schwerkolt Cottage project brought together my interests and experience in local history and heritage conservation. It also tapped into my amateur interest with historical archaeology. My first response to the significance of Schwerkolt Cottage was partly to do with its place in Victoria’s German heritage, as it reminded me of similar German farmhouses elsewhere in Melbourne. A few years earlier I had worked at Heritage Victoria on a project at Westgarthtown, a site with remnant German farmhouses in suburban Thomastown, and there seemed to be architectural similarities between the two sites.[2] At Heritage Victoria I also gained an understanding of historical archaeology through volunteering on digs at Cohen Place off Little Bourke Street and at Viewbank Homestead in the City of Banyule, and I had been involved with the assessment of the Lysterfield Boys Farm site for inclusion on the Victorian Heritage Register.[3] These experiences drew my attention to the ‘horse paddock’. When I visited in August, drifts of jonquil bulbs were scattered in disorderly clumps down the hill towards remnant fruit trees. Perhaps here was a potential site for further research below ground into how the Schwerkolt family had lived in the years prior to the construction of the second stone house. Local history had been central to my research into the early history of public housing in Melbourne, and its importance had been brought home to me in 1990 when I successfully argued for the preservation of buildings at 83–89 Montague St and 108–116 Gladstone St, South Melbourne.[4] The houses had no architectural merit but were evidence of early attempts by local councils to build low-cost working-class housing, and they represented a significant meeting between local history and the broader history of public housing provision in Victoria. The Schwerkolt precinct was a similar instance of a site where several parallel historical narratives merged.

This chapter explores the layers of heritage and historical meaning attached to Schwerkolt’s cottage: from its status as a modest example of a German farmhouse in colonial Victoria, to its evolution as an example of a local heritage conservation movement in the early 1960s. It considers the critical insights that the Schwerkolt precinct provides into the relationship between local history and heritage during the early 1960s and the contribution of local community activists to the evolution of the precinct as a site of local historical importance. Local historical perspectives are important, as this is where one feels the pulse of a community through a group or an individual, a significant site or building, and the fascinating interplay between local ideas and those exerting an influence from outside. The Schwerkolt precinct has all these qualities.

Layers of local history

The Schwerkolt heritage precinct is named after August and Paulina Schwerkolt, two German immigrant settlers who arrived in Victoria in 1849. By the 1860s they had established a farm beside Mullum Mullum Creek, or Deep Creek as it was known then, after buying 88 acres from Patrick Riley in 1861. Walking regularly from his home in Separation Street, Northcote, to Mitcham, August spent several years operating a business producing charcoal for blacksmiths from the trees he burned in the process of clearing the Mitcham property. By the mid-1860s he had completed his first cottage using local materials. The remnant plum and pear trees, a wine cellar and smokehouse provide evidence of the mixed farming that sustained the Schwerkolt family’s livelihood over the following years.[5]

Construction of the cottage that is the centrepiece of the heritage precinct began following the death of Paulina in 1884 and prior to August’s marriage to Wilhelmina Oppel in 1885. The building, completed after August’s death in January 1886, used the same local materials as in the first cottage with a design that was typical of German vernacular farmhouses.[6] When bushfires burnt the original stone cottage in 1905, a weatherboard house was built close by.[7] This third dwelling was destroyed by fire, possibly lit by vandals, in 1959 after part of the original property was sold to developers for subdivision.

Layered across the Schwerkolt farm narrative are other histories that link the local site to wider historical trends and events in the colonial period as well as to aspects of 20th-century history. In recent years, additional layers have been added, the most recent being the recognition that the Schwerkolt property is on land taken from the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung people. Now, amongst the plaques explaining each of the built exhibits, the farm machinery and the cottage garden, is one that acknowledges ‘the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung people as the Traditional Owners of the land’. This step towards reconciliation and acknowledgement of dispossession also acknowledges the consequences of colonisation that decimated Aboriginal people. The plaque text concludes with a sentence that ‘Whitehorse City Council recognises that the First Peoples and their cultures are an integral part of the Whitehorse community and broader Australian communities’.[8] The sign acknowledging First Nation sovereignty establishes a different context for Arthur Schwerkolt’s purchase of 88 acres from Patrick Riley in 1861. In the years between August’s purchase of land in 1861 and construction of a stone cottage in 1866, Wurundjeri and other Kulin were being moved to an Aboriginal reserve at Coranderrk under the control of the Board for Protection of Aborigines, near present-day Healesville. This overlooked aspect of the Schwerkolt precinct’s story provides potential for acknowledging further links in this history.

The site contains other connections to a wider German-Australian history during the colonial period and into the 20th century. These links reach from German immigration during the early years of colonial Victoria to the local architectural history of German vernacular farm buildings and the impact of the two world wars on Germans in Australia. One example of this perspective on the site’s history is the treatment of German-Australians during and after the First World War. The Versailles Treaty led to provisions giving the Commonwealth government power to confiscate and sell property owned by German nationals living outside Australia. August’s daughter from his second marriage, Mary Jackschkowsky, had inherited the property in 1909 and lived in the US but had married a German and happened to be in Germany visiting relatives at the outbreak of the war. Her husband was conscripted into the German army. As Mary was married to a German, she was considered to be German. Ownership of the Mitcham property and the other Schwerkolt property at Northcote remained in doubt throughout the 1920s as Mary attempted to convince the relevant authorities in Australia that she met the requirements of a hardship criteria. Under these criteria ‘enemy property’ could be returned if the individuals could prove that confiscation would cause undue hardship. Remarkably, letters from the German government were still being exchanged on this matter in the 1930s.[9] The issue remained unresolved until the planned demolition of the surviving cottage, combined with its intended purchase by the Nunawading council, forced a resolution and the abandonment of forced acquisition.

In 1963, a little over a century since August Schwerkolt began clearing the land for farming, the remaining property became the focus of a community conservation campaign that combined an interest in local history with local concerns about the destruction of native bushland and the loss of native landscapes. In what was almost a set piece for heritage conservation at the time, the Housing Commission of Victoria condemned the remaining cottage for demolition, which then set off a local campaign for the building’s preservation and a proposal to purchase the remaining part of the property for public use. This additional layer to the site’s local history became a story of local community activists who saved the cottage from demolition and the surrounding land from subdivision. Without their work and that of the municipal council, there would be no debate about how the past is made into history and heritage at this site.

The community campaign to conserve the Schwerkolt cottage brought it into the modern history of heritage conservation; in the process the old, condemned house became a heritage building. More broadly, the building became an expression of the wider growth in a heritage conservation movement in Victoria led by the National Trust. While heritage came to mean all those sites, buildings and objects in danger of being lost, the Schwerkolt cottage had an additional value to locals. Unlike other buildings that had a place on the National Trust’s list of significant heritage sites, Schwerkolt Cottage had no links with famous historical figures such as La Trobe’s Cottage — recently restored by the same architects who worked on Schwerkolt Cottage — nor was it an expression of architectural grandeur such as the stately Como House. The cottage appealed to locals who appreciated it as an expression of the ordinary, a characteristic that resonated with these new pioneers on the urban frontier who found a connection with the Schwerkolt family as pioneers.

As James Lesh has discussed, conservation was used to ‘valorise the built and social legacies of settler colonialism’, providing ‘an outlook by which the public might assert a continued sense of belonging in and possession of the settler-colonial city’.[10] Schwerkolt’s cottage fits this tradition, as it was seen locally as a modest expression of the pioneer legacy, but it also blended with wider community concerns across suburban Melbourne where local groups were active in landscape preservation and the conservation of native vegetation.

This episode of local activism was initiated in an emerging middle-class suburb on the urban fringes to the east of Melbourne and not in the inner suburbs where heritage conservation battles were typically fought at this time. In addition, the building attracted the attention of architectural celebrities such as Robin Boyd, and it also provided fuel for the heritage debate about the importance of conserving buildings that had no connection with the rich and famous but had value to a locality.

And so, in 1963, the Schwerkolt cottage was swept up in the National Trust’s broadening interest in heritage buildings, an interest which included other heritage items such as hitching posts, Aboriginal rock paintings, graves and concerns about landscape conservation.[11] Local councillors sought a National Trust classification as a way of affirming the cottage’s heritage significance and to halt the demolition order. The Trust gave the house a ‘D’ classification of ‘local historic significance’ that was later upgraded in 1964 to a ‘C’ as ‘notable and worthy of preservation’. The previously condemned house took a step towards becoming historic when heritage architects John and Phyllis Murphy offered their services to the Nunawading council at a fee of £10 and 10 shillings to restore August’s cottage. The Murphys’ approval of the cottage’s significance added further to the building’s historic status. The ‘old house on Deep Creek Road’ became ‘a pioneer cottage’.

The campaign to conserve the Schwerkolt cottage brought together twin concerns in the community of the history of the area and the loss of native landscapes as new suburban subdivisions were created. Over the years, the initial pioneer focus of the site shifted as other perspectives appeared in response to changes in the community around the precinct and as new understandings of the past emerged.

Landscape and local history

In 1960, Mitcham locals who noticed the Schwerkolt cottage may have thought of it as ‘the old house on Deep Creek Road’ and many knew it as the old Schwerkolt family home, but when the housing commission placed a demolition order on it, the building and the land assumed a new identity as a vanishing remnant of a pioneering past. The cottage became an example of a process that James Lesh has identified in the period at the beginning of the 1960s, when the age of a building and its value to a local community were often sufficient reasons to conserve locally significant places, and the threat of demolition invariably enhanced the value and significance of a building. This was the period before the ideas and practices about conservation became what Lesh identifies as ‘more methodological, complex, and specialised’.[12]

In Mitcham, the threat to the building fed into local political concerns about the loss of existing landscapes. Several councillors had already been elected on an environmental platform drawing on opposition in the community to widespread clearing of trees from the old orchard properties and of farmland for housing subdivisions, actions that were seen as destroying part of the ‘pioneer’ history of the area. Conservation of landscapes and historic buildings in Mitcham found an attentive audience in the National Trust, where support was given to protecting the old Schwerkolt cottage with a heritage listing that was sufficient to persuade the housing commission to withdraw the demolition order, so long as the building remained unoccupied.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, concern in the Nunawading municipality about the impact of an unplanned urban sprawl on the environment found a focus in local community politics. An aspect of the prevailing mood was evident in a letter to the council from one resident, Jean Field, who later became active in the conservation of the Schwerkolt cottage. In 1954 she wrote to the council suggesting a ‘printed form’ be enclosed with each building permit wherein the applicant would be asked, as they had chosen to live in Nunawading, to ‘acknowledge’ their ‘responsibility’ to the district by helping to preserve the natural trees on their land, ‘as these were one of the district’s main attractions [that] are being ruthlessly destroyed’.[13] There is no evidence that the council took up Field’s suggestion, but by 1959 the ongoing support for some type of control over land clearing had led to the formation of the Blackburn Tree Preservation Society. Among the society’s stated aims were the identification of sites for future parks and nature reserves, the planting of street trees in denuded areas, and the promotion of interest in the local area’s history. Although the society was based in Blackburn, it drew members from across the Nunawading municipality. Foundation members included individuals such as Keith Satchwell and Frank Burns, who were elected to Nunawading council in 1958 and 1959 respectively on a platform to protect native bushland.[14] Satchwell convened the first meeting of the local historical society. In 1966 George Cox, another foundation member and past president of the Blackburn Tree Preservation Society, was elected to council in what was considered ‘a great victory’ by some members of the society.[15] Cox was subsequently instrumental in the campaign to save the Schwerkolt cottage, as was Jean Field, who was also an early member of the society. Like Satchwell, Cox and Field were involved in the local historical society.

The overlapping memberships of community groups meant that wider debates about the loss of native landscapes merged with an interest in local history and to a popular valuing of an imagined pioneer heritage with its accompanying links to Australian nationalism. Given the continuities between local groups interested in landscape preservation and heritage conservation, it was not surprising that Keith Satchwell, for example, was active in bringing the possible preservation of the Schwerkolt house to the attention of council and then later leading a deputation of councillors to the National Trust. Thirty years later he reflected:

So I went along with a couple of other councillors and saw John Murphy who was the honorary architect to the National Trust; John and Phyllis Murphy in the 50s had been in the forefront of contemporary architecture. They were two of the architects who designed the Olympic Swimming Pool for us. And then their interest started to move to older buildings and they became active in restoring terraces around East Melbourne. So John said, “I will come out and have a look at the place.” So he came out and his eyes goggled and he said, “This is the best bit of organic architecture that I have ever seen.” He said he would like to take on the commission of restoring this place authentically.[16]

The combination of landscape preservation and heritage conservation was also reflected in the work of the National Trust. By 1964 the Trust was calling for ‘the urgency of conserving not only buildings, but also landscape, both urban and country’.[17] Professor J. S. Turner, Chairman of the National Trust Landscape Preservation Council, argued:

let us suppose that all the buildings classified by the Trust were destroyed. We would still be left with a magnificent city, developed on what was originally a poor site. Melbourne owes a great deal of its character to its generous central planning, its fine central parks, tree lined streets and boulevards. Destroy these and the city becomes a clean and lively beehive with pleasant but mostly undistinguished suburbs, steadily choking itself by an unplanned sprawl into the surrounding countryside.[18]

The Trust’s Landscape Preservation Council consisted of members from the Trust, but there were also others who were delegates from a range of environmental groups across Melbourne. Members were drawn from across the Nunawading municipal area, including some from the Blackburn Tree Preservation Society, while others were from the Save the Dandenongs and Yarra leagues, and from the Beaumaris Tree Preservation Society (which had been the model for the Blackburn group).

The connection between built heritage and landscape conservation, as Graeme Davison suggests, had its origins in 19th-century Australia. Identifying old buildings and landscapes with a sense of national heritage predated modern ideas associated with the heritage movement, so during the period under discussion it was only to be expected that members of the Blackburn Tree Preservation Society would also be associated with the creation of the Schwerkolt heritage precinct, and then the Nunawading Historical Society. These activists appeared to be in a tradition that Davison, for example, identifies as reaching back in the short term to the promoters of national parks and pioneer monuments earlier in the 20th century, and then in the long term back to the naturalists, anthropologists and painters of the 19th century.[19] Davison also contrasts the heritage movements of the 1960s and 1970s with their antecedents, arguing that earlier movements ‘were engaged in a systematic and more overtly nationalistic attempt to imbue the land with patriotic significance’ whereas the post-war heritage movement was more concerned with the material elements of heritage.[20] The local activists involved with the Schwerkolt cottage did not fit so neatly into this interpretation of a static pioneer legend, and both aspects were evident in the discussions about the Schwerkolt cottage.

When the restored cottage was officially opened in 1965, the event was a modern expression of the combined elements of Australian nationalism, colonial servitude, non-English speaking immigration and heritage. The Country Women’s Association had representatives; the President of the Folklore Council of Australia was present, as was the German consul and a speaker on German migration to Nunawading; there was a Queen’s Scout to open the door of the official limousine and following the formal vice-regal opening by the Victorian Governor, Sir Rohan Delacombe, singers and musicians performed Australian folk songs and the Ringwood Salvation Army Band played. In addition, the owners of heritage pioneer properties such as Mr and Mrs Stringer from Holly Green at Sunbury, ‘Victoria’s oldest homestead’, were involved.[21]

Local history expressed in terms of native vegetation and landscape connected to ‘pioneer heritage’ was a significant aspect of community thinking at the time. The Schwerkolt house was physical evidence of a fast-disappearing past. It fed the nostalgia of many of the new settlers for the reminders of an historic period that was daily becoming fainter with each new subdivision. Each demolished farmhouse, each orchard cleared of vegetation and subdivided by unmade roads, each poorly drained block of land with no underground sewerage seemed to create a chasm between an idealised past and an imperfect present.

The campaign to save the cottage was largely the result of the actions of local organisations that put up candidates at council elections who were then instrumental in drawing attention to the heritage value of the cottage. But it was the work of volunteers and skilled amateurs who delivered the heritage-listed cottage to the community.

Volunteers and amateurs

In 1965 Robin Boyd wrote in the Australian newspaper about how Australia was almost alone in the world in leaving ‘the preserving of historic relics’ to ‘volunteers and amateurs’. Boyd found consolation in the way that the Nunawading council had taken the initiative with the Schwerkolt cottage, enlisting the support of the National Trust and seeking advice from heritage architects on how best to conserve it.[22] To his mind, the professionals had triumphed over the rabble. But in the case of Nunawading, Boyd underestimated the significance, quality and effectiveness of the work undertaken by the ‘volunteers and amateurs’ in their ongoing conservation of what became the Schwerkolt heritage precinct.

The council and residents welcomed Boyd’s acknowledgement of their project, but they perhaps overlooked his criticism of the process that had brought about the saving of Schwerkolt cottage. His article drew attention to an aspect of understanding history and heritage at this time that was moving from an older, nationalistic, pioneering focus to a more material concept with clearly defined links to architectural history and principles that could be universally applied. Jean Field wrote to Boyd thanking him for his article and referring to how the project ‘set in 5½ acres of beautiful Australian parkland’ would provide a view of the ‘way in which our pioneer families lived’.[23] She ignored his disparaging view of ‘volunteers and amateurs’, but her comment about pioneers was exactly part of Boyd’s critique of how the assessment of heritage significance occurred in Australia. His professional concerns were the loss of architecture as developers demolished the ‘oldest and most interesting buildings’.[24] The families occupying these interesting buildings were of little interest.

Boyd’s support for the project was evidence of a wider interest in heritage conservation that extended across suburban Melbourne to country towns and even interstate. Support and interest in what was happening in Mitcham also came from suburban progress associations, historical societies, owners of historic buildings and architects. In a measure of how the building reached into the lived experience of people in the community, previous tenants even wrote to share memories of living in the house. Historical societies in Western Australia wrote to find out how something similar could be achieved in their own localities, while some correspondents wrote to affirm the conservation in terms of Australian nationalist sentiment. An architect, Ken Green, included a sketch of the cottage with his letter that took up a familiar theme of the pioneers and the threat to Australian traditions:

in its natural bush setting it evokes a picture of the early struggle for survival by our pioneers. This feeling should be preserved for our younger generations growing up in an atmosphere of “triple-fronted B.V. villas”. With the extensive influx of migrants, albeit they bring with them culture from the Continent, there is a danger that the traditions established in the early days will be lost unless steps are taken for their preservation.[25]

Lydia Chancellor (daughter of George Pethard, the owner of the Tarax soft drink firm in Bendigo) wrote, ‘it is heartening to know that in this age of demolition there are still some historically minded folk’.[26] One local resident in Mitcham was less enthusiastic, complaining that the conservation project was ridiculous. The land should have been developed and something practical done with it, as decent roads and public transport were more urgent to make getting to the shops easier and ‘if councillors had to walk to the shops several times they would be of the same opinion’.[27] Further research might reveal even greater divisions over the purchase of the Schwerkolt property. Yet the support for it suggests that volunteers and amateurs were a key ingredient in the council’s campaign to buy the property, particularly in the way this fed into prevailing social attitudes about pioneer culture and the preservation of native landscapes.

One of the amateurs who appeared to play an essential part in progressing the heritage assessment of the Schwerkolt cottage was Denice Moorhouse, whom the Council had employed to write a municipal history. Moorhouse was similar to several other interested women in this predominantly middle-class community. Like Jean Field she was a published author, and in common with many other women in the community she had stopped paid work to be at home with young children while her husband was in paid employment. She had previously worked in a local bank, had then begun an economics degree, then was employed teaching in a local secondary school until she had her first child, at which time she began writing articles for the local newspaper and reporting on council meetings. She would later reflect positively about working with the male councillors, who got to know her during this brief stint as a journalist. Her experience of researching and writing the municipal history while pregnant with her third child provides further insights into the creation of the Schwerkolt heritage precinct:

they were wonderful men — and yes, they were men, not women. I must be honest. Why did they pick me? I think they must have just liked my style … And I think I shocked a few people because in those days if you were 7 months pregnant you really should have been at home.[28]

But being pregnant with her third child also meant she was forced to stop writing at one point, although she was able to later do her research while she left the baby with her mother.[29] She later reflected that she ‘never had any intention of being a working mother but money was so short’.[30] At this time, in 1963, Nunawading councillors were also attempting to establish the heritage value of Schwerkolt’s cottage; the job of completing the initial National Trust heritage assessment fell to Moorhouse.[31] It seems she, rather than a professional architect, filled in the National Trust heritage listing form, as perhaps the language and detail of specific aspects of the building would have been expressed differently if it been completed by an architect. Her commonsense approach — in the manner of what Boyd would have called an amateur — was perceptive and clear in the way it identified the relevant aspects of the building. At times it almost mirrored much of what was contained in later formal legislation and was a measure of her understanding about heritage.

Her response to the National Trust criteria revealed how she distinguished between the historic and architectural assessment of the building. Guided by the criteria on the form from the National Trust’s Survey and Identification Committee, Moorhouse’s assessment of the site’s significance in November 1963 engaged with ideas about historical and architectural importance as separate criteria. She identified relevant building techniques and characteristics in a manner that suggests she may have consulted architects at the National Trust, but then her wry identification of the architectural style as ‘Australian colonial, if such a style is recognised’, suggests it is all her assessment. Her eye for detail, combined with information possibly gleaned from locals, helped her identification of significant elements under the criteria ‘Other Points of Historical Interest’:

Built in stone carted from the nearby Deep Creek and cemented together with mud … This home is typical of early homes in that no access is available from room to room within the house. It is necessary to leave the room and walk along the covered verandah to enter the next room. The fact that there is no sawn timber in the three original rooms is of interest.[32]

Moorhouse’s reference to the link between these pioneer settlers and the use of local materials brought a personal element to the discussion about the building as an expression of the pioneer legend. Like Jean Field, whose family had pastoral connections, Moorhouse’s grandparents’ experience of taking up land near Bathurst, where they lived in a wattle and daub hut, suggests the legacy of the pioneer legend was something personal to her.[33] For others it might have been an abstract exercise to address the National Trust’s criteria, but for Moorhouse it was possibly more immediate and tangible:

The fact that it is old (1860’s) does not make it of historical interest to the nation but adds to its aesthetic value in that the ability of the pioneers to make use of any available building material was a sound idea. Architecturally it is typical of the early Australian homes (working class, not wealthy landowners) and because it is situated within twelve miles of Melbourne its position is of importance. Many such old homes may be found in remote country areas, but very few within the metropolitan area.[34]

She is clearly less willing to accept the age of the house as just a simple measure of the site’s historic significance, and there is also perhaps an echo of Robin Boyd’s influence in her identification of the significant use of local materials in the building’s construction. Putting aside this aspect of her response, the ingredient that characterises local heritage is that it is personal in ways that are not immediately apparent.

Moorhouse’s commentary about class coincided with contemporary debates about how historical significance and heritage were not confined to the houses of ‘wealthy landowners’. Whether August Schwerkolt, a farmer, an owner of an agricultural business producing prize-winning wine and the proprietor of some prime agricultural land with a creek frontage close to the foothills of the Dandenongs could be called ‘working class’ is a moot point, but it spoke to a wider conversation at the time, and later, about the elitism of the National Trust. One newspaper article in the late 1960s headed ‘Como: snob value or historical value?’ was prompted by comments made by a Nunawading councillor critical of the Trust’s lack of ongoing support for the Schwerkolt cottage. In the early 1970s, the matter reappeared when Schwerkolt Cottage was omitted from the Trust’s list of recommended heritage sites for visitors to the Moomba Festival.[35] By the 1970s, the cottage had become, in the words of one writer, ‘a pretty little wine growers cottage with … period furnishings in [a] delightful setting … Alas, Schwerkolt was but a farmer, not a governor.’[36]

A brief reflection: Making public history

There were several insights I gained from working on the Schwerkolt project in 2001. In the beginning I was too dismissive of the local nostalgia attached to aspects of the historic precinct, and I did not stop to consider the local view of the cottage as a ‘pioneer farmhouse’, preferring instead an interpretation that linked the design of the house to German farmhouses in Doncaster and Kangaroo Ground and to Maltzahn’s farmhouse at Westgarthtown. I also overlooked why locals thought the herb garden and the cottage were considered unique in the history of the locality and in Victoria’s broader colonial history. The lesson for me was how the local community’s view was one of several ways of looking at the site; the stories of uniqueness were part of the overlay that had been added as local relationships with the site grew and public history was made.

There were several layers of meaning embedded in the cottage’s local significance. Some aspects did not necessarily align with archival records, but my academic interpretations did not take precedence over how locals might view the site. In 2001 I doubted the stories about how the cottage and its surrounds were unique by comparison with other remaining colonial sites in Victoria, but I began to realise these local stories were expressions of how the community found meaning in the place through the singular importance of the garden and the stone cottage and that my response was missing that point. I began to wonder about the domestic character of these perspectives and if these were a way that locals identified with the site and recognised the voluntary labour involved with its preservation that, as an outsider, I took for granted.

The herb garden around the cottage, for example, was thought to have been planted in the mid-1860s and was said to be the first herb garden in Victoria. Pat Faggetter, a trained horticulturist and an expert on herb gardens, volunteered her labour to recreate a 19th-century herb garden around the cottage, but it seems unlikely she would have thought it was the first herb garden in Victoria. I wondered if the claim was an expression of how locals saw the significance of the garden’s restoration at the time when the paid restoration of the cottage was also taking place. Adding to the significance of the garden was the voluntary labour of the women who created it and the role of Pat Faggetter, who was widely respected in the community for her involvement in other projects such as overseas aid, the Vermont Elderly People’s Homes and establishing the Mitcham Community Opportunity Shop. It became obvious to me why locals who had lived with the building for most of their lives, spending hours and hours devoted to its preservation and its functioning as an important local historical site, would see it as a link to a pioneering past.

But what contribution did our study make to understanding the heritage value of the precinct? Our ‘Summary of Significance’ drew attention to an array of elements linking the site to broader histories of 19th- and 20th-century Victoria and Australia. The summary referred to the treatment of German-Australians during the First World War and identified the association with German settlement of colonial Victoria and the link to German vernacular traditions of construction. Other aspects included the site’s connection with Melbourne’s early conservation movement and the significance of the ‘horse paddock’ in the domestic and economic history of the site, evident in the remnant orchard and a Canary Island date palm (Phoenix canariensis).[37] In the years since our report, other heritage studies and further research by members of the Whitehorse Historical Society have revised details at the site and aspects of its significance. The ‘horse paddock’ has now been included as part of the precinct, one consequence of which has been the correction of the order in which the three houses were built. Our report continued a longstanding error nominating a weatherboard house built on the ‘horse paddock’ as the second house, when recent research has identified it as the third house (see Figure 3). Signs now draw attention to the archaeological significance of the former ‘horse paddock’ and its placement on the Victorian Heritage Register. A sign attached to an architect-designed machinery shed completed in 2007 now welcomes visitors to ‘Schwerkolt Cottage and Orchard’.

Schwerkolt Cottage has a unique local status that has become embedded in the history of the place. Although it has acquired meanings over the years that might not appeal to academic historians, it also remains a dynamic, organic, vital and significant community focus — and obviously a place to provoke the historical imagination. The location continues to evolve. The ‘original pioneer cottage’ is now recognised on a plaque as the second house built on the site and that it was constructed in the 1880s, while other elements of the site have also shifted in their importance.

Aspects of the site have changed over the years, but it remains an expression of one view of the local history. The precinct continues to present an interpretation of the cottage’s history embedded in a pioneer view of colonial history, yet for it to remain relevant it must begin to further acknowledge the dispossession of the original Wurundjeri people, as traditional country was divided and subdivided by white colonists to become the individual possessions of later settlers and immigrants. To ignore the consequences of dispossession is to retell only part of the rich human history that is embedded on this land from successive waves of occupiers; to overlook this aspect seems to devalue the efforts made by those individuals in the 1960s who saw Schwerkolt Cottage as a site of struggle in a way that reflected their views of the time. In the 21st century there is a need for similar optimism to tell stories that are inclusive and to acknowledge diversity.

Conclusion

There are several parallel interpretations of the Schwerkolt precinct. One view is that the building is a document open to interpretation while others see its importance as a representative antique fixed in a time that has passed yet at the same time giving meaning to the present. For many who actively advocated for its preservation in the first place, it was a shrine to a valorised pioneer past. The property now sits at an intersection where views of the past meet and continue to evolve as further research leads to new perspectives about the site. Its heritage or historic significance continues to grow as the council commissions heritage assessments and as new members continue to join the historical society.

There are few places where a large local history archive exists beside a local history museum in the grounds of a significant heritage a significant heritage site — a site saved by earlier members of the voluntary organisation that now runs the archive. This is indeed an extraordinary place. If the site continues to evolve, it will be an inclusive expression of the changing currents of public history and historical understanding in the local community.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Heather Goodall, Chris McConville and Caroline Wallace for their comments on early drafts of this paper. I also acknowledge Rosalie Whalen, Vicki Jones-Evans and Robyn Harvey at the Whitehorse Historical Society for their assistance with research.

- Michele Summerton and David Wixted, “Schwerkolt Cottage and Museum Complex: Conservation Analysis & Management Plan” (City of Whitehorse, April 2002), 10. ↵

- Robert Wuchatsch and David Harris, Westgarthtown (Whittlesea: Heritage Council and the City of Whittlesea, 1998); Robert Wuchatsch, Westgarthtown: The German Settlement at Thomastown, (Melbourne: Robert N. Wuchatsch, 1985). ↵

- “Lysterfield Boys Farm Site” (Victorian Heritage Database Report), Heritage Council of Victoria, accessed May 27, 2024, https://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/places/11485/download-report. ↵

- The houses had not been included in previous conservation studies conducted by heritage architects and had also been overlooked by the National Trust. It was a clear illustration of how the historic context of buildings remains an important element in establishing heritage significance. At the time of the hearing, it was unusual for a building to be given a classification solely on its historic links. The architect representing the developer at the hearing understandably confined his arguments to the absence of architectural value in the buildings. ↵

- Diane Sydenham, Windows on Nunawading (North Melbourne: Hargreen Publishing in conjunction with the City of Nunawading, 1990); Niall Brennan, A History of Nunawading (Melbourne: Hawthorn Press, 1972); Ted Arrowsmith, Schwerkolt Cottage and Museum: The legacy of the Johann August Schwerkolt, Pioneer (City of Whitehorse and Whitehorse Historical Society Inc., 2004). ↵

- Summerton and Wixted, “Schwerkolt Cottage and Museum Complex,” 10. ↵

- Whitehorse Historical Society Archive NP1343. ↵

- Whitehorse City Council plaque “First Peoples” created in consultation with and with permission from the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation. ↵

- Rosalie Schwerkolt Whalen, The Amazing life of Mary Schwerkolt (Whitehorse Historical Society Inc. Schwerkolt Cottage and Museum Complex, 2017). ↵

- James Lesh, Values in Cities: Urban Heritage in Twentieth-Century Australia (Milton: Taylor & Francis Group, 2022), 6. ↵

- Graeme Davison, “Heritage: From Patrimony to Pastiche,” in Use and Abuse of Australian History (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2000), 113. ↵

- Lesh, Values in Cities, 4. ↵

- Unit 20 Nunawading Council Minutes, Vol 20 17, May 1954-4 October 1954, 441, PROV VPRS 8112/P0001. ↵

- David Berry, ed., Fighting for the Trees: The Story of the Blackburn and District Tree Preservation Society (Nunawading: Blackburn and District Tree Preservation Society, 2017), 8. ↵

- Laurel Jones letter re Blackburn Tree Preservation Society, Blackburn Tree Preservation Society, accessed November 17, 2023, https://bdtps.wordpress.com/historical-documents/; David Berry, Fighting for the Trees, 10. ↵

- “Nunawading Historical Society 30th Anniversary 1995 transcript” (transcribed by Rosalie Whalen, 2023), Whitehorse Historical Society Archive ND7966. ↵

- J. S. Turner, “Landscape and Townscape,” Trust: A Quarterly from the National Trust of Australia (Victoria) (February 1964), 3. ↵

- Turner, “Landscape,” 3–4. ↵

- Davison, “Heritage,” 118. ↵

- Davison, “Heritage”. ↵

- Unit 408 City of Nunawading General Correspondence Subject Files Box P1/46 (1–8) Part 3, ‘Schwerkolt Cottage Opening’, PROV VPRS 9545/P0001. ↵

- Robin Boyd, “Our History Under Fire,” Australian, 23 October 1965, 9. ↵

- Jean Field to Robyn Boyd, 1 November 1965, Schwerkolt Cottage Committee of Management, Box 1 Correspondence 1965/78, Whitehorse Historical Society ND 3759. ↵

- Boyd, “History”. ↵

- Kenneth Green to Nunawading Council, 29 April 1964, Unit 408 City of Nunawading General Correspondence Subject Files Box P1/46 (1–8), Part 2, PROV VPRS 9545/P0001. ↵

- Lydia Chancellor to Nunawading Council, 5 April 1964, PROV VPRS 9545/P0001. ↵

- “Irate resident” to Nunawading Council, 6 April 1964, PROV VPRS 9545/P0001. ↵

- Denice Moorhouse talk, 10 February 1996, AV0018 Whitehorse Historical Society, accessed December 10, 2023, https://victoriancollections.net.au/items/60d923316e5f99545134f902. ↵

- Jocelyn Moorhouse, Unconditional Love (Melbourne: Text Publishing Company, 2023), 1–5. ↵

- Denice Moorhouse talk, Whitehorse Historical Society. ↵

- Unit 408 City of Nunawading General Correspondence Subject Files Box P1/46 (1-8) Part 1, PROV VPRS 9545/P0001. ↵

- National Trust of Australia (Victoria) file 1644/6 Historical Research and Data Collecting Auxiliary, 28 November 1963, 2. ↵

- Jocelyn Moorhouse, Unconditional Love, 25–26. Her favourite painting was Fred McCubbin’s triptych The Pioneers. In the final panel of the painting, where a figure looks at a grave and towards a city on the horizon, she believed it illustrated how succeeding generations easily forgot the experiences of the pioneer. ↵

- National Trust, 1. ↵

- Nunawading Gazette, 3 April 1968. ↵

- Nunawading Gazette, 14 March 1973. ↵

- Summerton and Wixted, i–iii. Sadly, the drifts of jonquil bulbs that used to appear in August no longer bloom, as the paddock is now a park that is regularly mowed. ↵