Chapter 2: Angels of History: Public Histories as Advocacy and Activism

Liz Conor

The best portmanteaus of ‘academic’ and ‘activist’ are ‘activemic’ or ‘acadivist’. Similarly clumsy attempts to bring these descriptors together include ‘acadissident’, more broadly ‘public intellectual’, and more recently ‘historical advocate’. While much thought is given to the relation of art to activism, intersecting academia and activism is difficult, and it describes a dissonance many of us live with.[1] We tear ourselves away from the rare books collection in Melbourne’s State Library to join a rally on its front steps. Yet I rarely see colleagues at a blockade, nor comrades at a conference. While activism is an embodiment of public history, it is inherently connected to history in the public sphere, yet these can seem like worlds apart, lived separately as ‘symptomatic of deep contradictions in social life’, itself a working definition for praxis.[2] In this chapter I rethink the scholarship on praxis in an attempt to resolve the dissonance between activism and academia.

It is difficult for academics to find time to bring to bear the understandings painstakingly accrued as humanities researchers in an organisational setting such as a community NGO. In many ways research, teaching and publishing in and of themselves are interventionist. As students we have been, and we see our current students, influenced and informed by activism on campus and beyond. We may also hope for similar impacts and outcomes, or ‘public engagement’ in our readers. Many historians have consequently been drawn to the historiography of activism – such as documenting the militant organising of suffragettes, or the daily acts of quotidian resistance by Aboriginal domestic workers, or the US civil rights movement – hoping their work will inform strategic public interventions into the present from these lessons from the past. It is why we are committed to writing history ‘against the grain’.[3] But researching and teaching in universities while involved in community campaigning requires holding them in productive tension, which can be quite a juggle. How do we bring into synthesis or ‘sublate’ the dialectic of our academic and activist lives, competing and harried as they are?[4] One starting point may be revisiting the theory of praxis.

***

The notion of praxis derives from a long philosophical tradition reaching back to Aristotle. His schematic of praxis is worth understanding as the basis for the development of this concept and why it has been drawn upon by theorists seeking change over centuries. For Aristotle, praxis referred to acts performed for their own sake or doing. He distinguished praxis from poiesis, namely productive activity in the pursuit of ends or making, and then again from theoria, which is contemplation or thinking.[5] German-born political economist and revolutionary socialist Karl Marx (1818–1883) revived the notion of praxis in two of his early works: the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 and the Theses on Feuerbach (1845). He wrote, ‘Philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it’.[6] This attention to humans’ practical relation to the world was for Marx how his readers could influence social life. Marxism as a political philosophy has been described (by Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci [1891–1937], in his Prison Notebooks) as a ‘philosophy of praxis’ because it is geared toward action and societal change.[7] Indeed, Marx’s central theory of ‘historical materialism’ claims that the struggle between different social classes is what propels historical change, and these classes and their struggle are grounded in the underlying economic base. This theory has been described as ‘a theory of society conceived with practical intent.’[8]

For those of us who like to thumb critical theory while lying in front of mining haul trucks, praxis has an immediate appeal. It could help us understand what we’re attempting in our dual lives, and offer some guidance toward reconciling them, by seeing our scholarship effect the change we crave, most urgently within the climate emergency – to which I will return in the last section. But first the complexity and development of the concept has to be unpacked if it is going to be useful to us.

As it stands praxis is a surprisingly elusive concept. It appears in the title of some feminist articles on intersectionality,[9] which refers to ‘the interconnected nature of social categories such as race, class, and gender, creating overlapping systems of discrimination’.[10] Yet the meaning of praxis is often assumed for the reader and the term regularly goes undefined. At its simplest it is the practice of ideas, of putting ideas into practice. It is often described within Marxism as ‘the unity of theory and practice’, through ‘ongoing sequences of organized, theory-informed political activity’.[11] Through the rubric of praxis, theoretical abstractions are ‘traced back to their roots in concrete social conditions’;[12] that is, knowledge is understood as being produced within material contexts of social activity, and for Marx specifically within modes of economic production. Social change or transition depends on the coinciding of our objective social circumstances with our complete understanding of those circumstances. For political theorist Hannah Arendt (1906–1975), praxis realises the active life; moreover, action is a mode of human togetherness which fosters participatory democracy. For literary historian György Lukács (1885–1971), praxis combines critical reflection and action, thus mediating both theory and practice.[13] For Gramsci, praxis connects diverse practices and instances within a concrete historical unity.[14]

As such praxis has been exhaustively debated by Marxists, not least in the critical tradition of the Frankfurt School, founded in 1923, which brought together sociologists to critique the commodification of culture and its distraction of the working class from their exploitation under capitalism. Social theorist Jurgen Habermas (1929–), for one, argued that action-oriented theories ‘can only be translated into processes of enlightenment which are rich in political consequences when the institutional preconditions for practical discourse among the general public are fulfilled.’[15] For Habermas, those preconditions are grounded in a functioning public sphere, and particularly a fourth estate or press culture, that can hold power to account. Ever interested in the institutional preconditions of the public sphere, Habermas would have called the concentration of Australian media out as an instance of the ‘immunizing power of ideologies’ through which the ‘dominant tradition’ is ‘surreptitiously incorporated in the symbolic structures of the systems of speech and action’.[16] Reflecting on Rupert Murdoch’s multinational mass media News Corp and its recent content deal with OpenAI, it’s helpful to apply Habermas’ 1971 observation that:

the ever more densely strung communications network of the electronic mass media today is organized in such a manner that it controls the loyalty of a depoliticized population, rather than serving to make the social and state controls in turn subject to a decentralized and uninhibited discursive formation of the public will, channeled in such a way as to be of consequence.[17]

Habermas saw early trends in the concentration of ownership in media communications as obstructing an enlightened common will intent on social change. Clearly, whatever the form of our public advocacy, it takes place within certain contingencies of communication, namely the present day mediascape.

What interests me here is whether practice can inform theory enough within these contingencies, silos and constraints. Are we sufficiently ‘subjecting theory to the requirements of political action’?[18] Are theories of social change informed by the effective strategies and tactical interventions of non-violent direct action? Is thought as active as action or speech as conduct? How do we bring all to bear on the crisis that is global heating before it’s too late?

***

The climate crisis constitutes a new catalyst for massive social transition. It harbours all of the elements that Marx believed can carry through the thwarted project of social transformation.[19] Namely, the mode of production of the carbon-based economy is manifestly out of step with new directions in the productive forces of renewables, reviving an antagonism toward capitalism. In the climate justice movement we see this countertendency emerging in new forms of opposition in response to environmental crises – mostly spatial obstructions in the flow of the military–industrial complex via sit-ins, lock-ons, occupations, blockades and of course strikes, all of which piggyback on the obstructions of the anti-globalisation movement. It is unassailable to most people now that a consequence of capitalism is the domination of nature and unchecked resource extraction and that we are on the precipice of biosystemic collapse, including the slowing of AMOC (Atlantic meridional overturning circulation), salination of the oceans, glacier melt in the Andes and on the Tibetan Plateau – on which one-sixth of the world’s population depends for freshwater – to give just a few examples of major tipping points in our climate system.

Nothing brought this dreadful awakening home to me quite like my sister’s home burning to the ground on Black Saturday, February 2009. We picked her up from the emergency station in Diamond Creek. She was covered in scratches from cutting back the bush around her block all day. My nieces sported ember burns. Their ears were full of soot, their faces numb with shock. Our home became a relief centre. The next morning there was a trail of ash down the centre of the bath – the last remnants of their cherished bush home. Rinsing that trail of ash down the plughole, I experienced the first moments of what Maoist theorist Alain Badiou describes as ‘someone who decides to be faithful to an event that rips apart the fabric of his/her purely individualistic and lacklustre experience’.[20] As a print historian I started trying to nut out what spectacle I could base a climate justice campaign on. The climate justice movement as a global phenomenon is missing a unifying visual trope (it could also use an anthem).

As a student I had been involved in the Greens for years, running twice on the Victorian senate ticket and then for Deputy Lord Mayor of Melbourne. I had also set up a number of campaigns: CASVP, the Coalition Against Sexual Violence Propaganda; The Mothers of Intervention on maternity leave; Stick with Wik on Native Title; and the theatre protest groups the John Howard Ladies Auxiliary Fanclub, the Climate Guardian Angels and most recently the Coalettes. All drew on the understandings I was gaining as an undergraduate into our mediascape and how it has been and can be used for social change.

CASVP tried to bring destructive representations of sexual violence (not necessarily explicit or pornographic) to media attention through mostly radio and TV interviews coming from press releases demanding government intervention into sexual violence propaganda. This very quickly got caught up in censorship debates, and what has since been dubbed carceral feminism. I was out of my depth and the campaign foundered. This prompted me to make pornography debates the subject of my honours thesis. I remain convinced that explicit representations are not in themselves damaging to gender relations, but when sexual violence is eroticised, just as when domestic violence is romanticised, we need to think very carefully about legislative regulation, censorship and vilification.[21]

The Mothers of Intervention sought more supports for mothers in terms of work-life balance. We staged a media stunt, burning maternity bras on the steps of Parliament, which drew 10 camera crews … but it did not attract mothers, some of whom said they felt very attached or nostalgic about their maternity bras. None of the footage appeared in the news cycle and the campaign continued as a radio show on 3CR, called Radiomama, with Zelda Grimshaw.

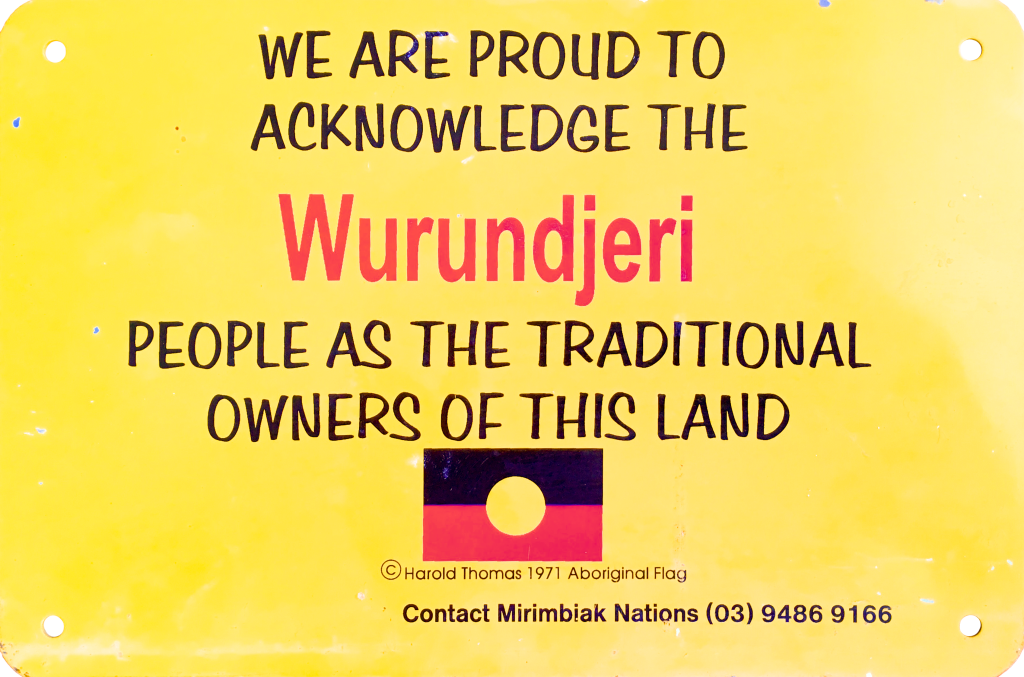

The Stick with Wik campaign was in reaction to John Howard’s scuttling of the High Court Wik decision, which would have enshrined coexistence on pastoral leases. We made armbands and sold them through the Bodyshop after a massive fundraiser gig headlined by Midnight Oil and Paul Kelly. We made the yellow house plaques that still festoon Melbourne, mostly prompted by acknowledgements of country that, at that stage – the end of the 1990s – were only happening at academic and activist events. We passed on those materials to Australians for Native Title and Reconciliation (ANTaR) when I was pregnant with my first daughter, and I had to get a first draft of my PhD finished.

The John Howard Ladies Auxiliary Fanclub was a theatre troupe of women chasing Howard around his morning walks with mock adoration. We tried to hand him a race card, offered him yellow cake on doilied Queen’s Green crockery and made video clips that satirised his policies. We donned what we dubbed the Cronulla Cape (Australian flag), wore white blindfolds and intercepted him at every opportunity, becoming a fixture on the election hustings.

The Climate Guardian Angels were inspired by Allana Beltran’s Weld Angel, one of the more powerful media interventions in environmental activism in recent history. A troupe of seven of us in giant organza wings either backdropped politicians we supported or intercepted those who were denying and delaying the science on climate change. We were there, standing outside Parc des Expositions in the Paris suburb of Le Bourget, as the delegates to the COP21 filed into their meeting. This gained us international press and a front cover on The Age.

Currently I’m working on another theatre troupe, the Coalettes. As 1940s cinema usherettes we proffer trays of coal, trying to sell this ‘stranded asset’ to passers-by. We nearly intercepted Scott Morrison on the hustings at Studley Park but missed him by a few hours. As Boris Groys argues, ‘Art becomes politically effective only when it is made beyond or outside the art market – in the context of direct political propaganda’.[22] While Groys is focused on Soviet Realism, there is scope within his argument for spectacle-based activism. In what follows I’ll reflect on my most impactful campaign: the Climate Guardian Angels.

After the Black Saturday fires of 2009, CSIRO climate scientists, many summarily sacked under the Howard and Abbott governments,[23] noted that under a 2° Celcius rise in temperature, already unavoidable, such firestorms would rip through Southeast Australia every three to five years, and we saw this in the Black Summer of 2019–2020. While my sister and her family trudged off to countless funerals, I stepped into what Badiou would regard as a different ontology or subjectivity. Badiou reorients critical theory toward ontology, arguing that ‘a subject is someone who is faithful to a foundational event, which brings about a truth capable of orienting life (a truth of a political, scientific, artistic or amorous nature)’.[24] As a Greens senate candidate, I’d already been following climate change and watching aghast the incipient warping of governance in what we now call the ‘energy wars’. Black Saturday made me a climate activist. But being appointed in an Australian university and with new babies meant I didn’t have time for it. I’m now moving into energy history in an attempt to bring these rupturing moments, and those we see in daily headlines, into some form of critically informed praxis in my own research. But before this there was more spectacle-based campaigning.

After Black Saturday I set up the Climate Guardian Angels with activist and author Deborah Hart in early 2013.[25] Deborah was then involved with the Friends of the Earth Quit Coal campaign. She was driven and connected, which gave our campaign such a head start. After bringing our satirical street theatre troupe the John Howard Ladies Auxiliary Fanclub before the public with comrade and peer Zelda Grimshaw, we’d pondered what kind of fan club of adoring women fitted with then Prime Minister Tony Abbott – Nuns in Lycra? Zelda and I met at La Trobe as students and have collaborated for years on a number of the campaigns mentioned above. Also critical to all of these campaigns and their materials was the extraordinary artist Deborah Kelly. I’ve since realised no fan club applied to Tony Abbott because women generally disliked him.

Champing at the bit for some kind of action on climate change, I wrote a piece that ABC’s The Drum ran over the Christmas week in December 2013. It was titled ‘We are Guardians of the Future’.[26] I did a word association, guardian-angel, and then a Google search and found Allana Beltran’s Weld Angel.[27] I’d seen it, I think in the Monthly, but now her extraordinary 2007 intervention struck me as the basis for a new activist theatre troupe. I contacted her and through her friendship with Deborah Hart she endorsed our campaign proposal and, on some ‘visitations’, got involved. But was bringing together these understandings of mediascapes and the climate crisis effective praxis? As a media historian, I knew spectacle had a very particular utility within the sight-grab news economy in which you have approximately 8 seconds to get your message across. Any spectacle has to convey a complex whorl of meaning immediately.

While searching ‘angels’, also there on Google was surrealist artist Paul Klee’s (1879–1940) Angelus Novus, a 1920 oil transfer drawing that Walter Benjamin first owned and that now has renewed significance under the looming threat of environmental collapse.[28] Benjamin (1892–1940) himself is another (!) Marxist theorist, focused on media, most influentially in his wonderful essay, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ (1935). Benjamin reflected on Klee’s Angelus with characteristic poetic force and theoretical inference:

A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.[29]

It’s a complex passage. Benjamin was criticising what Stalin was doing to the Marxian method of historical materialism. He was rejecting that history is a continuum of progress, inhering a logic of change (that manifests as revolutionary class struggle), but rather saw it as an unceasing cycle of destruction. But it is his reading of this image – of being propelled helplessly by the forces of progress, or ‘growth’, into a future full of foreboding – that so resonates now. How evocative that pile now seems in the era of the Anthropocene: the carcasses of extinction, or indeed of half the world’s wild animals dead in the past four decades,[30] of a million birds killed each day by Australian domestic cats;[31] or the ineradicability of plastic, where every piece produced still exists, pulverised into microbeads, a toxic miasma insinuating itself into all corners of the biosphere, altering the composition of aquatic systems and appearing in our very brain stems;[32] and the reef – tragically it is terminal, and many of us now carry around reef grief and reef rage.[33] This is the storm of ‘progress’ the Climate Guardian Angels tried to pivot against, to turn our backs on, while Klee’s Angelus was propelled backward.

Remember too that Benjamin wrote this while displaced as a Jewish refugee, stranded on the Spanish–French border, before self-administering a fatal dose of morphine as he watched France fall to the Nazis. In Benjamin’s tragic circumstances we’re faced with the numbing realisation that the pile of debris is comprised of people too. Indeed, current projections estimate tens of millions of people will be forced from their homes by climate change in the next decade alone, creating the biggest refugee crisis the world has ever seen,[34] and triggering the boundary paranoia of proto-nationalism in its inexorable march toward conflict. This is set out with frightening clarity in Andreas Malm’s Black Skin, White Fuel, in which he charts the rise of the right in Europe on a platform of anti-immigration, and how and why fossil fuel corporations funded their rise.[35]

When he took flight, Benjamin entrusted Klee’s New Angel to philosopher Georges Bataille (1897–1962) in Paris, who passed it on to Theodor Adorno (1903–1969, social theorist of the Frankfurt school). Klee’s Angel transferred through the hands of some of the key critical thinkers of the 20th century. It is now held in the Israel Museum, which resituates it in a site of destruction as Netanyahu’s disproportionate response to the Hamas October 7 attack further alienates the globe to Israel’s ongoing occupation of Gaza and the West Bank.[36] Given the Climate Guardian Angels were informed by Benjamin’s critical engagement with Klee’s Angel, did our non-violent direct action in turn critically inform new theories of climate justice? In a recent chapter by Denise Varney in her co-edited collection Feminist Ecologies, the Climate Guardian Angels are invoked as doing precisely that.[37] Varney focuses on our intervention over two weeks in Paris during COP21.

Behind the scenes, other aspects of our campaign, beyond the content of the spectacle and actions, are instructive; we might call them praxical. Namely what came to the fore in those intense weeks of intervention in Paris – under high security due to the terrorist attacks only a month prior – was the campaign’s internal organisation, how decision-making was shared, inclusivity among the nearly 100 on-call Angels who were mobilised for our direct actions, the rationale of where and whom we blockaded, police and media liaison, and unavoidably, labour and volunteering, maintaining the campaign materials, who owned the means of production, creative custodianship and finally, how and by whom all this would be remembered and to what end? There was also ambiguity around deploying a normative feminine trope, all in white. Doing street theatre in the crosshairs of the November 2015 Paris terrorist attacks and the subsequent state of emergency security overlay was daunting and highly complex. Internal campaign organisation in such protesting scenarios requires transparent, accountable and inclusive decision-making and an enormous amount of goodwill to manage; for example, there might be trauma arising from violent policing among comrades from previous protests. Praxis then requires far more than outward show. It also needs to enable participatory democracy within activist organisational structure and strategy.

On our return to Melbourne I reflected on one moment, in Dancehouse Diary:

When the Bataclan Theatre was sprayed with bullets we debated whether to take the Angels to a city that was burying its dead. The evocations of Angels as carriers of souls to the ‘next world’ could well subsume our intention to evoke an image of messengers of unheeded dangers, and protectors of future generations. When deploying spectacle in activism the circumstances in which you project your image can be more determining of its meaning than the hours of careful deliberation over its visual content.

At a banned rally in the Place de la République I felt acutely out-of-place as we circled its statue, where Parisians had lain thousands of flowers and lit hundreds of candles for their dead. We were climate activists paying our respects at this elaborated site of grief and we found ourselves stepping into another realm of evocation, of meeting death with some suggestion of knowing its end, one none of us believed in as committed atheists, and one which possibly offended Parisians whose faiths imagined Angels very differently.

So too when we followed the human chain protest down the Boulevard Voltaire unwittingly past the Bataclan itself, and the other sites where the dead were commemorated with piles of flowers lying wilt in the frost. Here the photos of those killed were pinned in plastic sleeves to the barriers with handwritten dedications. It was as acutely, desperately riven a site I have ever stood in. We were a procession of Angels through a traumascape. A man caught my eye as though looking for a reification or maybe a depository of his horror. He shook his head slightly, in incomprehension at what surrounded us, and I nodded back weakly. We neither could take it in. I was so at a loss I kept swinging around and bashing Deb in the face with the aluminium frame supporting our wings. Something utterly inarticulate and illegible sundered and the Angels stood in a plot they did not belong.[38]

It is impossible to predict the circumstances in which the spectacle you’ve so carefully calibrated, drawing upon every possible interpretation, will ultimately appear, and the overlay or lens through which it will be perceived. Paris was a profound moment in registering the care you need to take in proffering protest spectacle through trauma and mediascapes.

***

What is clearer each day is that we humans stand on another historical precipice now, one prefigured by Benjamin, and made all the more vivid and menacing by climate change. By theorising feminist and environmental activism as praxis we stand with Klee’s ‘angel of history’, our backs turned to ‘progress’, to say that this history casts a different light on contemporary notions of ‘growth’. We turn to the countless activists of the climate justice movement who have stood with the Angelus Novus to say that unchecked extraction for consumption doesn’t look much like ‘progress’ to us. We ask: what kind of a future lies before us if the march of all-consuming, extractivist ‘progress’ or ‘growth’ isn’t obstructed and brought a halt? But we can’t pose this question without imagining ways to combine critical and creative intellectuality with non-violent direct action. The importance of history is that, as intellectual Marcel Gauchet says, ‘without philosophical insight into the historical situation facing us, political action can only be blind’.[39] Critically and publicly engaged history-making then becomes the ‘guideline to present action’.[40]

Academics who are activists are acutely aware of the historical significance of the campaigns we work on, which often relate directly to our research. Sometimes they are our fieldwork, which we undertake with an ethic of care in the research of human subjects and communities, sometimes our communities, using a ‘critical pedagogy [of] community-based research’.[41] The strategies we deploy are informed directly by years of theorising and histories of feminist and environmental and increasingly First Nations resistance. But these activist strategies need to also inform the ways we both remember and theorise, or historicise, resistance. Do we turn our back on the storm of ‘progress’ while helplessly propelled into its maelstrom, or do we face this cycle of despair – adrift on what feminist ecologist Val Plumwood describes as ‘the ship of rational fools’[42] – stand up, get in the way, and make the future ours?

- See for example, Grant Kester, ed. Art Activism, and Oppositionality: Essays from Afterimage (Duke University Press, 1998). ↵

- Andrew Feenberg, The Philosophy of Praxis: Marx, Lukács, and the Frankfurt School (London: Verso, 2014), 26. ↵

- Walter Benjamin, “Thesis on the Philosophy of History” [1940] in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Shocken, 1969), 257. ↵

- Dialectic: preserving the useful portion of an idea, thing, society, etc., while moving beyond its limitations. ↵

- If Marx was conforming to Aristotle, he arguably would have drawn on poiesis instead of praxis. Richard Kilminster, “Praxis,” in The Blackwell Dictionary of Twentieth-Century Social Thought, eds William Outhwaite and Tom Bottomore (Oxford: Blackwell, 1993). ↵

- Karl Marx, “Theses on Feuerbach” [1845], Marxists Internet Archive (Lawrence and Wishart), https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/theses/theses.htm, accessed February 12, 2024. ↵

- ‘In this way we also arrive at a fusion, a making into one, of “philosophy and politics,” of thinking and acting, in other words we arrive at a philosophy of praxis.’ Antonio Gramsci, Further Selections from the Prison Notebooks, ed. and trans Derek Boothman (University of Minnesota Press, 1994), Notebook 7, 35. ↵

- Jurgen Habermas, Theory and Practice (Boston: Beacon Press, 1971), 3. ↵

- Elizabeth Evans, “Intersectionality as feminist praxis in the UK,” Women’s Studies International Forum 59 (November–December 2016): 67–75. ↵

- Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 2015. See https://www.cjr.org/language_corner/intersectionality.php Accessed 20 August 2024. ↵

- Kilminster, “Praxis,” 508. ↵

- Feenberg, The Philosophy of Praxis, 29. ↵

- Georg Lukacs, “Towards a Methodology of the Problem of Organisation” [1923], Marxists Internet Archive (Lawrence and Wishart), https://www.marxists.org/archive/lukacs/works/history/ch08.htm, accessed 16 September 2025. ↵

- W. F. Haug, “Gramsci’s ‘Philosophy of Praxis’: Camouflage or Refoundation of Marxist Thought”, Wolfgang Fritz Haug, http://www.wolfgangfritzhaug.inkrit.de/documents/Gramsci-PhilPraxis.pdf. ↵

- Habermas, Theory and Practice, 3. ↵

- Habermas, Theory and Practice, 12, 14. ↵

- Habermas, Theory and Practice, 4. See also Guardian staff and agencies, “OpenAI and Wall Street Journal Owner News Corp Sign Content Deal,” Guardian, May 23, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/article/2024/may/22/openai-chatgpt-news-corp-deal. ↵

- Habermas, Theory and Practice, 4. ↵

- Feenberg, The Philosophy of Praxis, 30. ↵

- Alain Badiou and Marcel Gauchet, What is to be Done? A Dialogue on Communism, Capitalism and the Future of Democracy (Cambridge: Polity, 2016), 134. ↵

- See Judith Butler, Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative (New York: Routledge, 1997). ↵

- Boris Groys, Art Power (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008), 7. ↵

- Peter Hannon, “Climate Science to be Gutted as CSIRO Swings Jobs Axe,” Sydney Morning Herald, February 4, 2016, https://www.smh.com.au/environment/climate-change/climate-will-be-all-gone-as-csiro-swings-jobs-axe-scientists-say-20160204-gml7jy.html; and Michael Slezak, “Australia’s Shortage of Climate Scientists puts Country at Serious Risk, Report Finds,” Guardian, August 3, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/aug/03/australias-shortage-of-climate-scientists-puts-country-at-serious-risk-report-find. ↵

- Badiou and Gauchet, What is to be Done?, x. ↵

- Larissa Dubecki, “Environment Activists Plan to Defy Paris Ban on Protests at UN Climate Conference,” Sydney Morning Herald, November 27, 2015, https://www.smh.com.au/environment/environment-activists-plan-to-defy-paris-ban-on-protests-at-un-climate-conference-20151127-gl9hj1.html. ↵

- Liz Conor, “We are the Guardians of the Future,” ABC News, December 28, 2012, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-12-28/conor-we-are-guardians-of-the-future/4445102. ↵

- “The Weld Angel,”, Allana Beltran, accessed July 17, 2018, http://www.allanabeltran.com/weld-angel.html. ↵

- Klee’s oil transfer had been adhered to an 1838 copper-plate engraving by Friedrich Muller after a Lucas Cranach portrait of Martin Luther. See Hollan Cotter, “R. H. Quaytman’s Variations on Klee’s Angel,” New York Times, November 15, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/06/arts/design/rh-quaytmans-variations-on-klees-angel.html. ↵

- Benjamin, “Thesis on the Philosophy of History,” 249. ↵

- Damian Carrington, “Earth has Lost Half of its Wildlife in the Past 40 Years,” Guardian, October 1, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/sep/29/earth-lost-50-wildlife-in-40-years-wwf. ↵

- John Woinarski, Brett Murphy, Leigh-Ann Woolley, Sarah Legge, Stephen Garnett and Tim Doherty, “Cats Kill More Than 1 Million Birds in Australia Every Day, New Estimates Show,” ABC News, October 4, 2017, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-10-04/cats-killing-one-million-birds-in-australia-every-day-estimates/9013960. ↵

- Louise Tosetto, Culum Brown and Jane Williamson, “How Microplastics Make Their Way up the Ocean Food Chain Into Fish,” The Conversation, December 1, 2016, https://theconversation.com/how-microplastics-make-their-way-up-the-ocean-food-chain-into-fish-69148. ↵

- Lauren E. James, “Half of the Great Barrier Reef Is Dead,” National Geographic (August 2018). ↵

- Matthew Tyler, “Climate Change ‘Will Create World’s Biggest Refugee Crisis’,” Guardian, November 2, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/nov/02/climate-change-will-create-worlds-biggest-refugee-crisis. ↵

- Andreas Malm and the Zetkin Collective, Black Skin, White Fuel: On the Danger of Fossil Fascism (Verso, 2021). ↵

- Ester Muchawsky-Schnapper, “Paul Klee’s ‘Angelus Novus’, Walter Benjamin and Gershom Sholem”, Israel Museum Journal VIII: 47–52, https://www.imj.org.il/en/collections/199799-0. See also my discussion in Liz Conor, “White Lies: Netanyahu’s Propaganda War on Gaza,” Overland, March 21, 2024, https://overland.org.au/2024/03/white-lies-netanyahus-propaganda-war-on-gaza/. ↵

- Denise Varney, “Climate Guardian Angels: Feminist Ecology and the Activist Tradition,” in Feminist Ecologies: Changing Environments in the Anthropocene, eds Lara Stevens, Peta Tait, Denise Varney (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 135–153. ↵

- Liz Conor, “Dancing on the Pinhead of Resistance,” Dancehouse Diary, Issue #10: The Many & The Few – Assembling the Political (June 2018), https://www.dancehousediary.com.au/?author_name=liz-conor. ↵

- Badiou and Gauchet, What is to be Done?, 13. ↵

- Badiou and Gauchet, What is to be Done?, 13. ↵

- Caitlin Cahill, David Alberto Quijada Cerecer and Matt Bradley “ ‘Dreaming of …’: Reflections on Participatory Action Research as a Feminist Praxis of Critical Hope”, Affilia Journal of Women and Social Work 25, no. 4 (2010): 406–416. ↵

- Feminist Ecologies, 101. ↵