3 Assessment Design Principles

How can we turn assessment for inclusion concepts into principles for action?

What aspects of assessment influence students the most?

What might inclusive assessment design look like?

Remember when Covid-19 caused a ‘pivot,’ including changes such as shifting examinations online, using technology, increasing time limits, and moving to open-book examinations? This had a perhaps unexpected but incredibly useful impact of increased inclusion for many students, who were able to use familiar equipment in spaces they had adapted to their own needs (Tai et al., 2023). Staff implementation of access requirements and assessment flexibility also increased.

However, as the ‘return to campus’ was orchestrated, previous flexible arrangements that had become the ‘new normal’ were often rescinded. Though assessment changes have been the most likely of Covid-related changes to remain, there is still much that we can do to improve assessment design for inclusion, and the recent pandemic demonstrates just how possible some of these changes are (Broadbent et al 2023). Universities and lecturers need to carefully consider how time, technology, equipment and materials contribute to inclusion or exclusion.

The multiple tensions in assessment

From an institutional perspective, assessment is used to ascertain students have met the appropriate outcomes at the requisite level. This is important for certification and validation of qualifications. Due to the high-stakes nature of this process for each individual student, it is extremely important that students are not disadvantaged or excluded on the basis of characteristics or abilities that are unrelated to the outcomes being judged.

However, due to assessment task design and implementation, constructs unrelated to the learning outcomes often impact on success – even when accommodations are applied. For instance, in a project on students’ experiences of inclusion in exams, Ellie, who was studying a health professional degree and had dyslexia, recounted one of her experiences:

“It was an exam that tested your knowledge on medical terminology, and the pathophysiologies behind multiple conditions.

They did things like crossword puzzles and then you might have a sentence which has been broken into four sections, and then jumbled up so you have to put the sentence in order. You had to put your corresponding number to the order that should be matched with the jumbled-up sentences. Okay, firstly, the sentences are jumbled up, it’s in a box that’s so small and then you have to put numbers with it. I don’t think that’s a true measure of testing someone’s intelligence in regard to content.

Then, they were asking us certain things like spelling, like you have to spell these really, really long words correctly. It might be like, ‘What is the medical terminology for this?’ The word could be so ridiculously long, and my scribe might not know how to spell it, and then I would be trying to phonetically spell things out, and if I couldn’t get it right, my scribe would get really flustered and I just missed out on marks.”

(data from Tai et al., 2022)

In this example, there are multiple challenges which the task creates for the student due to her dyslexia, including aspects related to the layout (i.e., small boxes), structure (i.e., jumbled sentences), and foci (i.e., spelling), none of which seem to align with the stated learning outcome, which was the knowledge of medical terminology. In instances like this, assessment should be revisited with a close focus on the learning outcomes. For example, the first two problems Eliza experienced are probably able to be eliminated by changing the task, since neither format is necessary to use. The final one, spelling, is a bit more complicated. Here, staff need to consider if correct spelling is or is not actually a learning outcome. If spelling is an important part of learning and communicating medical terminology, it needs to be stated so students understand it is a requirement and the reasons for this, with appropriate support offered.

Students also prefer assessments that help them connect to their future goals. For example, Eliza noted:

“The career path that I’m following, you can’t do it at home, you have to go into the clinic, you have to be scrutinised by the doctors checking your work. I feel it’s something that you need to get used to doing.” (Tai, Mahoney, et al., 2023, p. 396)

This example illustrates how students might see that more authentic forms of assessment are inclusive of their futures. In these situations, it can also be helpful to consider what types of authentic restrictions or affordances might be available within a workplace or other environment where they might apply their skills (Tai, Ajjawi, et al., 2023).

There is a moral obligation for universities not to act directly or indirectly to disadvantage those enrolled. Beyond this prevention of negative experiences, we might also have positive duties to ensure students are supported in their learning and assessment, in a similar way to how sex discrimination legislation now requires ‘proactive and meaningful action’ from employers to prevent and eliminate sexual harassment, discrimination, and violence (Australian Human Rights Commission, 2024).

Previous justifications for inclusion and fairness of assessment focused on population level outcomes, with abstract ideas of what happens in assessment. Instead, we argue (in alignment with McArthur’s 2018 work on Assessment for Social Justice) that we also need to focus on how students actually experience assessment.

Principled Assessment for inclusion

There are many ways to conceptualise assessment design. Frequently constructive alignment (Biggs, 1999) is invoked as the mainstay of assessment design: this requires learning objectives, learning activities, and assessment tasks to align with each other, and moreover, that students actively participate or engage in the activities in ways that allow them to construct their own learning. This approach suggests that for assessment to be inclusive, it’s not just the end task that matters, but also all the processes and activities that lead up to the task. Students agree with this: in a project exploring diverse students’ perspectives on assessment, Tai, Dollinger and colleagues (2023) found that aspects such as assessment timing, instructions, information, and interactions with staff, as well as broader access to learning resources, were all part of what made assessment inclusive.

Tai, Ajjawi, et al. (2023) offer three design principles which may help to ensure diverse students are not disadvantaged through assessment.

| Design principle | Why this approach is inclusive | How you might apply it |

| Authenticity in assessment | Can support students in their diverse future goals and help students to build capabilities which are useful beyond the university. Can represent diverse values, contexts, and situations within tasks, and provide real-world situations which students can see apply to them. Students can ‘try out’ tasks and roles to understand possible future opportunities. |

|

| Programmatic assessment | Offers multiple opportunities to be assessed and receive information on performance to inform improvement and support student development. When decisions about progress/certification are made on an accumulation of tasks, this allows for students with fluctuating conditions/unexpected circumstances to ensure their best performances are included. Requires clarity and communication of learning outcomes. |

|

| Assessment for distinctiveness | Highlights the importance of diversity and difference, and that students, across their assessments, can compile or curate their distinctive set of capabilities to be prepared for their unique post-university destinations. Offers opportunities for capabilities to be demonstrated in different ways. |

|

Remember, designing assessment for inclusion doesn’t mean you remove all challenge from the assessment. Rather, the task should be explicitly scaffolded within the course and assessment design, and proactively consider different potential outcomes and formats. To do this, we need to start from the learning objectives and consider the priorities and what is important. This might also involve reconsidering learning objectives to remove extraneous or irrelevant components. For example, if the learning objective is “to write an essay on schools of philosophy”, is the writing of a comparative essay the important capability, or are you more interested in how the student understand the history of philosophy? If both are important, how can you make this clear through your unpacking of criteria?

Then, you might consider assessment design and its subsequent practice by all involved. It might be that there are different ways to think about meeting the objectives (e.g. might students prefer to discuss orally or record a video), some of which might be more appropriate than others in particular contexts. There might also be considerations about what level of pre-existing capability or understanding students have about assessment formats; if nobody knows what a video essay is, then you will need to teach them about this in addition to the content/topic.

Being inclusive is about offering everyone the opportunity to do their best rather than restricting possibilities for high performance to those who already happen to know how to effectively work in specific genres.

Another approach to designing assessment for inclusion

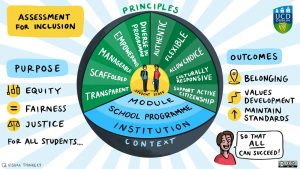

Colleagues at University College Dublin (UCD, 2024) also offer an alternative approach to designing assessment for inclusion. In September 2024, they launched an Assessment for Inclusion Framework designed to ensure equity, fairness and justice for all students. The Assessment for Inclusion Framework is based on 10 Design Principles to maximise the chance of success for all students, and in partnership with those students. These design principles are not intended for every individual assessment task, activity or method, but serve to create an assessment literacy for the development of inclusive assessment practices and policies. As a starting point, think about the diversity of student cohort, the context (discipline, programme, module, etc.) and the stakeholders.

Colleagues at the University College of Dublin, including Sheena Hyland and Geraldine O’Neill, have also developed a framework for assessment for inclusion.

This framework includes a series of ten principles as represented in the diagram above, with a contextual focus to promote outcomes of belonging, values development, and the maintenance of standards for all to succeed.

In their elaboration on the framework, they also highlight three phases of implementation actions:

- cultivating self-awareness

-

use the Assessment for Inclusion Design Principles: Considering where to start

-

operationalise processes for change

The framework drills deep down into assessment for inclusion design and practice at individual, team, and programmatic levels, and offers a scaffolded and well- linked pathway for developing practice. Below, Associate Professor Geraldine O’Neill introduces the University College Dublin Assessment for Inclusion framework.

University College Dublin Assessment for Inclusion Framework: Principles and Practices by Professor Geraldine O’Neill for Quality and Qualifications Ireland

When introducing inclusive assessment, there is a greater likelihood this will ensure sustainable assessment in action (where students learn to self-assess their own learning long after the programme or course) in workplaces and community contexts. For inclusive assessment to be sustainable, we are reminded of Boud’s seminal work on sustainable assessment where he argued that it enables “students to meet their own future learning needs” (Boud, 2000, p. 151). It is recognised also, that this means the power relationship between teachers and learners needs to change. Students trialling this approach in a student-staff partnership identified how this worked for them and ironically how it shifted their focus from assessment and on to their learning, and for teachers “partnership in the assessment process allows us to know our students and to provide them with a range of means to show what they understand” (Bourke, Rainier & de Vries, 2018, p. 10).

Questions for reflection

- In your context, which purposes of assessment are most prominent?

- At your institution, what do you think the level of self-awareness is regarding inclusive assessment practices?

- For the students you encounter, what might their main motivations to participate in assessment be?

- How much do your assessments focus on the present, and how much do they consider the future of students and society?

References

Ajjawi, R., Tai, J., Dollinger, M., Dawson, P., Boud, D., & Bearman, M. (2023). From authentic assessment to authenticity in assessment: Broadening perspectives. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2023.2271193

Australian Human Rights Commission. (n.d.). The Positive Duty in the Sex Discrimination Act | Australian Human Rights Commission. https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/sex-discrimination/positive-duty-sex-discrimination-act

Boud, D. (2000). Sustainable assessment: Rethinking assessment for the learning society. Studies in Continuing Education, 22(2), 511–167.

Bourke, R., Rainier, C., & de Vries, V. (2018). Assessment and learning together in higher education. Teaching and Learning Together in Higher Education, 25. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1194&context=tlthe

Broadbent, J., Ajjawi, R., Bearman, M., Boud, D., & Dawson, P. (2023). Beyond emergency remote teaching: Did the pandemic lead to lasting change in university courses? International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00428-z

McArthur, J. (2018). Assessment for Social Justice: Perspectives and Practices within Higher Education. Bloomsbury Academic.

Tai, J., Ajjawi, R., Bearman, M., Dargusch, J., Dracup, M., Harris, L., & Mahoney, P. (2022). Re-imagining exams: How do assessment adjustments impact on inclusion? National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education. https://www.acses.edu.au/research-policies/assessment-adjustments-impact-inclusion-2/

Tai, J., Ajjawi, R., Bearman, M., Boud, D., Dawson, P., & Jorre de St Jorre, T. (2023). Assessment for inclusion: Rethinking contemporary strategies in assessment design. Higher Education Research & Development, 42(2), 483–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2022.2057451

Tai, J., Dollinger, M., Ajjawi, R., Jorre de St Jorre, T., Krattli, S., McCarthy, D., & Prezioso, D. (2023). Designing assessment for inclusion: An exploration of diverse students’ assessment experiences. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 48(3), 403–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2022.2082373

Tai, J., Mahoney, P., Ajjawi, R., Bearman, M., Dargusch, J., Dracup, M., & Harris, L. (2023). How are examinations inclusive for students with disabilities in higher education? A sociomaterial analysis. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 48(3), 390–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2022.2077910

Quality and Qualification Ireland (QQI). (29 Apr 2024). UCD Assessment for Inclusion Framework: Principles and Practices. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/UG4Gvlt_vjA?si=vQBtXfDQqglYlVui

UCD (2024). Assessment for Inclusion Framework. University College, Dublin. https://www.ucd.ie/teaching/resources/inclusiveandinterculturallearning/ucdassessmentforinclusionframework/