6 Opportunities and Challenges for Changing Assessment

What opportunities and challenges exist to implementing or changing different forms of assessment?

How have others tried to address these challenges and take advantage of opportunities?

We have all experienced some of the recent big disruptors to higher education systems: COVID-19, the rise of Generative AI, mergers, restructures, policy changes, and funding changes. While many people don’t feel comfortable with change and the disruption it brings, these broader forces can also represent an opportunity to grow more inclusive practices.

One way to think about opportunities and challenges is situating them not as an individual responsibility or problem, but as issues that exist within systems that shape the way that things unfold in higher education.

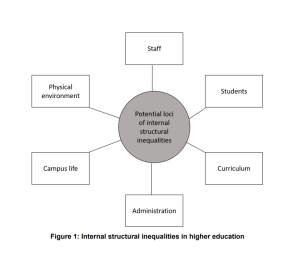

Naylor and Mifsud (2019) argued that the ways we view these institutional qualities and systems of practice are important for reducing structural inequality, and promoting success for all students. They identified “six dimensions of university activity that may act as potential loci for internal structural inequalities…these areas may be ‘pressure points’ or areas where internal inequalities may arise or be reduced — they are not aspects of university activity that necessarily promote structural inequality, and institutions may productively focus on different areas as necessitated by their individual cultures or the requirements of their student cohort” (Naylor & Mifsud, 2019, pp. 2-3).

Taking these six dimensions into consideration, you might consider how the ways that institutional structures and systems expect or determine a particular way of doing things can help or hinder the way assessment is undertaken and experienced, and how each of these areas can influence outcomes to perpetuate or minimise inequalities. Here are some more granular sub-examples of Naylor and Mifsud’s dimensions for you to consider that relate directly to inclusion in assessment

In your context, are these opportunities, challenges, or some of both?

Staff

- Staff attitudes, capability, and motivation

- Pedagogies: general practices and discipline-specific instructional trends

- Socio-cultural factors in delivery: lecturer-specific ‘styles’, institutional cultures, disciplinary approaches

Students

- Students’ expectations of assessment, stigma around identification of equity markers, and staff-student relationships,

- Student cohort characteristics which influence curriculum delivery

- Student group expectations around hybrid learning developed in respond to COVID-19

Curriculum

- Curriculum design conventions in each discipline and academic traditions.

- Industry input into curricula, professional association literature, accreditation requirements, and competences

Administration

- Teaching and learning strategy and policies and administration resources

- AQF levels and related learning outcome phrasings

- Promotion and teaching award criteria, innovation and quality incentives

- Assessment design and quality assurance procedures: review processes, templates, options (e.g., word counts / equivalencies, approved assessment genres and descriptions)

Campus life (i.e. extra-curricular opportunities)

- Presence and role of an accessibility service

- Opportunities for students from diverse backgrounds to be included in conversations about assessment and feedback

- Support services available to students

Physical Environment

- Accessibility support plug-in tools for learning management systems (e.g., Blackboard Ally) different educational technology uses, innovation tagging on units to include students’ feedback

- Academic integrity technology and tools and the student experience of these

- Campus (spaces and technology), physical accessibility and design, online/hybrid modes

While there is some crossover between categories, these categories can support identification of what different strategies might be useful to employ. For instance, a physical environment focus on assessment might identify that redesigning a laboratory environment could be an opportunity to improve inclusion for lab-based assessments. Alternatively, an administrative focus might suggest implementing a policy that students can take their lab-assessment in a different environment. Here’s a small interactive activity for you to consider what might be an enabler or a barrier within your context.

desert under starry sky in this activity by Mohammad Alizade on Unsplash used under the Unsplash License

How can we do our best within an imperfect and complex system?

You have likely realised that many aspects of the environment can operate both as an enabler and a barrier. In the examples from our research, both practitioners and senior leaders chose particular ways to work within their institutions’ systems and processes. For example, senior leaders might take a ‘ hands off’ approach, allowing implementers to innovate. Practitioners described being creative in their practices of centring students’ needs within assessment design priorities. Across the interviews we conducted in the CAULLT project (Harris et al., 2025), there were three opportunities (or challenges) that stood out as particularly important. Next, we summarise some of the different ways strategies were adopted to take advantage of these opportunities.

Introducing flexibility for the range of diverse students within a course

Leaders suggested strategies that could assist at a whole of university, program and unit levels and within particular discipline areas:

Whole of university (mainly administrative)

- Policy implementation of using ‘or equivalent’ for word counts, allows for more choice around the format of the task (e.g., oral instead of written – essay of 3000 words equivalent to a 5-minute video), offering equivalent assessments for supplementary tasks including allowing submission in a different form to the original assessment (e.g., Viva).

- Using a checklist to prompt assessment designers to include the following tools that diverse students can access: downloadable versions of tasks, non-written content labelled to allow screen readers to read these for students, videos with transcripts, assessment guides with voice-overs, and illustrated PDFs of tasks.

- Considering how the requirement to purchase textbooks for assessment tasks could disadvantage low SES students and providing an alternative way for students to engage with content.

- Offering short automatic assessment extensions without evidence (assisting students with complex circumstances, removing the role of the course coordinator/convenor as ‘judge’, and allowing students who may need to apply for special consideration the time to gain appropriate documentation).

Program or discipline area (administrative)

- Completing an overall assessment audit across a school/program enables staff to consider the design of assessment and assessment schedules to better support diverse students (e.g., not putting all of the assessment in one week, ensuring a range of assessment types are employed across a program).

Unit or module level (mainly student and curriculum focussed)

- Allowing students to create their own assessment schedules by allowing students to select their task deadlines from a range of options.

- Providing flexibility of scheduling for timed assessment tasks to support students with complex life circumstances (e.g., examinations are open for 24-48 hours vs at a specified start time).

- Providing the option of a ‘negotiated’ assessment, allowing students choice in what type of assessment they use to demonstrate the learning outcomes.

- Allowing for student choice in assessment topic or the focus of an assessment piece (e.g., a business of their choice becomes the topic of a marketing plan) and/or in the grade they wish to target (students can choose to complete particular parts of a task to achieve a designated grade).

- Allowing for student choice in the number of assessment topics to complete across a unit (e.g., students complete between 5-10 possible small assessments with the best 5 marks counted towards an overall level of achievement).

Workload management to afford implementation of inclusive assessment

Especially in larger courses, workload was identified as a challenge for staff trying to implement inclusive assessment, and something to be addressed. Colleagues explored different approaches that could be considered as acting upon different structural aspects:

- Staff: Including workload recognition/time for developing and implementing inclusive assessment

- Administration: Automating 5-day extensions to reduce staff administrative workload

- Student: Building in peer assessment as part of group work assessments to reduce lecturer feedback in large courses

- Physical environment: Using technology/software that provides customised formative feedback prompts for each individual student.

Concerns about Generative AI use and assessment authorship

Across higher education, universities are adopting strategies to manage the now widespread access to generative artificial intelligence (Gen AI). For some courses, programs, and universities, there has been a move back towards invigilated exams, whereas in others, this disruptor has encouraged the development and implementation of assessment genres which are harder to get Gen AI to write (e.g., reflection-based assessments). In these decisions, consideration of both the student and curriculum are necessary.

- Curriculum: Considering other ways to design assessments that are at a lower risk of AI plagiarism but which also may simultaneously promote inclusion (e.g., tasks which promote reflection or discuss students’ process, including a viva where students explain their work, creation of an artifact),

- Student: Allowing students to use AI, which can be very helpful for students with particular types of disabilities, but expect students to report their use of AI and the purpose of that use.

We recognise that readers of this resource might be operating at different levels within the institution, and so not all strategies are available to all who are interested in promoting more inclusive assessment. For instance, a sessional lecturer would not be able to automate extensions across a program of study. Similarly, an Associate Dean Learning and Teaching would not be the one offering to negotiate assignment due dates with individual students. Whilst a structural approach might be useful for identifying the types of strategies and a locus of action, we also need some way of considering how people with different roles within the university environment can all contribute to improving assessment for inclusion.

Questions for reflection

- What opportunities do you see within your university for promoting more inclusive approaches to assessment?

- What challenges to inclusive assessment are particularly salient to you and your team? What can you proactively do to mitigate these challenges?

- How can you best facilitate collaboration between people from differing areas and levels of responsibility within your university?? What might be some productive ways to work together to promote assessment inclusion?

References

Harris, L.R., Dargusch, J., Tai, J., Funk, J., & Bourke, R. (2025). Supporting leadership in inclusive assessment policy and practice: Final report. CAULLT, Sydney, New South Wales. https://www.caullt.edu.au/project/supporting-leadership-in-inclusive-assessment-policy-and-practice/

Naylor, R., & Mifsud, N. (2019). Structural inequality in higher education: Creating institutional cultures that enable all students. ACSES (Formerly NCSEHE), Curtin University. https://www.acses.edu.au/research-policies/structural-inequality-in-higher-education-creating-institutional-cultures-that-enable-all-students-2/