1 Orientation

Learning objectives

Learning objectives

On completion of this Chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand why it is useful to study this subject

- Know where to look for a case

- Know how to find an Act

- Know how to read an Act.

Key terms

Key terms

At the beginning of each chapter, you will find words/terms that you may not have encountered before. If you come across a word as you are reading and you are not sure what it means, check and see if the meaning of the word is in ‘Key terms’. The key terms will often be highlighted throughout the chapter for your ease of reference. Below are some examples from Chapter 2:

-

- Citation: a reference where to find a case in a law report or online.

- Civil law system: a complete legal system with its origins in Roman law and the Napoleonic Code.

- Common law: that part of English law developed from the common custom of the country as administered by the common law courts.

- Customary law: the term used to describe the common law rights and interests of tribal people in land according to their laws, traditions and customs.

- Equity: fairness or natural justice.

Introduction

Introduction

Why study Business Law?

Introduction to Business Law introduces you to an area of life that you probably have not thought much about the law and can’t see much relevance for you because you are not studying to be a lawyer, yet. But you may change your mind after you have finished this Unit. But despite what you may think, an understanding of what we will cover in this subject/unit will be both relevant and useful for you in the future. It is not boring (well perhaps a little bit in parts) or scary (there is a lot of reading) and if you do the Readings and look at what goes on around you, you will realise that it is all very relevant.

It is important to understand that you are not studying Introduction to Business Law to be a lawyer but rather to obtain a basic understanding of the relevance of Business Law in the context of business and commerce, and also what you do in your personal life - for example, like shopping which is all about contract law, consumer protection and the tort of negligence.

By the end of this subject/unit, the hope we have is that you will have a basic understanding of how the legal system works and how laws are created, but also that you will be able to recognise a legal problem coming your way and be proactive in taking appropriate steps to ensure that the problem can be resolved in your favour.

Note: The online reference materials, although referenced throughout this book, are supplementary and while not necessary, will help you to understand the core content of this unit. Further, all Acts and legislation mentioned can be considered PNG Acts and legislation unless otherwise indicated.

Chapter contents

As noted above, this subject/unit is hopefully going to provide you with an understanding of four different areas of law – negligence, contract, consumer protection and agency - that are useful for you in business and commerce, as well as being relevant in your personal lives.

The purpose of this Chapter is not only an introduction to what to expect in the coming 6 weeks but to also provide you with an overview of how to plan your study in the subject/unit, how to understand a case, how to read an Act, and how to write an essay.

See the table under the heading What do you need to know about module readings? to learn more about what readings to complete and when during the unit.

What is a study session planner?

The first thing to organise is a study session planner and the second thing to do is to stick to it (so tick the boxes as you read through the planner).

Study session planner

| Before you begin | Suggested study time | Done (tick off) |

|---|---|---|

| Find your way around the Blackboard site (try opening the URLs) | 20 minutes | |

| Read the Unit Outline (it tells you about the Unit and learning resources) |

10 minutes | |

| Read the Unit Content (it tells you what will be covered in the subject) | 10 minutes | |

| Read the Learning Objectives for each Module | 5 minutes | |

| Read the assessment (so you understand what you need to do to pass) |

10 minutes | |

| Check out My Readings (so you know what to read and how big each chapter is [are you a slow reader or a fast reader?]) |

15 minutes | |

| Check out Learning Help (important if you run into problems) | 10 minutes | |

| Total | 80 minutes |

Now that you have your Study Plan sorted, have a look at the following suggested study sessions below for each Module. You really need to be disciplined and try and cover each topic in the time allocated (but you can adjust it as everyone reads at different speeds and writes different amounts of notes. Try and keep your notes short and to the point). Remember, a good set of notes is important when it comes to understanding, remembering and applying what you have read.

What is a module planner?

A module planner will help you track your progress in the unit. Use the following module planners to guide your studies over the next 6 weekly study sessions.

Module Planner – Topic 1: Introduction to law

| Module 1 topics | Suggested study time | Done (tick off) |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction to the PNG legal system | 90 minutes | |

| Sources of law | 60 minutes | |

| The role of the police, the courts, and the parties | 60 minutes | |

| Precedent and statute law | 90 minutes | |

| What is negligence? – duty, breach, damage, defences, damages | 7 hours | |

| Other areas of tort law and duty of care | 90 minutes | |

| Revision question | 2.5 hours | |

| Total study time | 16 hours |

Module Planner – Topic 2: Making a contract

| Module 2 topics | Suggested study time | Done (tick off) |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction to contract | 90 minutes | |

| Agreement | 5 hours | |

| Intention to create legal relations | 90 minutes | |

| Consideration | 3 hours | |

| Revision questions | 2.5 hours | |

| Total study time | 13.5 hours |

Module Planner – Topic 3: Validity

| Module 3 topics | Suggested study time | Done (tick off) |

|---|---|---|

| Capicity | 90 minutes | |

| Consent | 3 hours | |

| Legality | 3 hours | |

| Form | 30 minutes | |

| Revision questions | 2.5 hours | |

| Total study time | 10.5 hours |

Module Planner – Topic 4: Construction of the contract

| Module 4 topics | Suggested study time | Done (tick off) |

|---|---|---|

| Representations | 90 minutes | |

| Parol Evidence Rule | 90 minutes | |

| Collateral contracts | 60 minutes | |

| How important is the term – conditions, warranties, innominate | 2 hours | |

| Implied terms | 2 hours | |

| Exclusion clauses | 3 hours | |

| What is the standing of third parties? | 90 minutes | |

| Revision questions | 2.5 hours | |

| Total study time | 15 hours |

Module Planner – Topic 5: Discharge and breach

| Module 5 topics | Suggested study time | Done (tick off) |

|---|---|---|

| Privity of contract | 90 minutes | |

| Discharge of a contract | 3 hours | |

| Breach | 90 minutes | |

| Frustration and force majeure | 2 hours | |

| Remedies | 3 hours | |

| Damages at common law | 90 minutes | |

| Damages in equity | 60 minutes | |

| Revision questions | 2.5 hours | |

| Total study time | 16 hours |

Module Planner – Topic 6: Consumer Protection and Agency

| Module 6 topics | Suggested study time | Done (tick off) |

|---|---|---|

| The Goods Act | 4 hours | |

| Independent Consumer and Competition Commission | 60 minutes | |

| Packaging Law | 60 minutes | |

| Commercial advertising | 60 minutes | |

| Fairness of Transactions Act | 2 hours | |

| What is agency? | 60 minutes | |

| Different classes of agency | 60 minutes | |

| Appointment of an agent and their authority | 2 hours | |

| Obligations of an agent and principal | 2 hours | |

| Termination of an agency agreement | 90 minutes | |

| Remedies for breach | 90 minutes | |

| Revision questions | 2.5 hours | |

| Total study time | 20.5 hours |

What do you need to know about module readings?

The times set down in the Module Planners above are approximate times it will take you to read through a topic. It is hard to be accurate when it comes to reading times because everybody reads at a different pace, however, the times above will give you a starting point.

The table below provides you with an overview of readings for each of the Modules. Try and read each chapter carefully. A highlighter can be very useful to highlight key points and things you might not understand. A good idea is to use two (2) different highlighter colours, one for key points and the other for what you don’t understand. It makes revision much easier and the more you read, the more you will comprehend.

LEGL1007 Introduction to the Business Law of Papua New Guinea

| Modules | Readings |

|---|---|

| Introduction | Chapter 1: Introduction to the legal system in Papua New Guinea |

| Module 1

The Papua New Guinean Legal System and Introduction to Negligence |

Chapter 2: Legal Foundations |

| Module 2

Making a Contract — Intention, Agreement and Consideration |

Chapter 4: Introduction to contract law |

| Module 3

Making a Contract — Capacity, Genuine Consent, Legality and Form |

Chapter 8: Capacity of the Parties |

| Module 4

Construction of the Contract |

Chapter 11: Construction of the Contract: Terms and Conditions |

| Module 5

Discharge and Breach of Contracts |

Chapter 12: Discharge and Breach of Contract |

| Module 6

Consumer Protection and the role of agency in the supply of Goods and Services |

Chapter 13: Consumer Protection |

Some tips on studying Business Law

What problems with words are you likely to encounter?

Studying a law subject is not quite the same as studying a lot of your other subjects/units. You will find that the chapters are different from what you are used to as a lot of the language appears, at first glance, to be ‘foreign’. This is because the law is about language and how we interpret the meaning of words in documents, as well as Acts and regulations, from which we develop legal rules and principles. Here are some words to watch out for when reading legal documents, legislation, or texts.

‘Means’ versus ‘includes’

Definitions of words and expressions in legislation will often commence with either ‘means’ or ‘includes’.

- ‘Means’ is used when the draftsperson wants the defined words to have an exact meaning. These can be found in the Interpretation section of an Act. For example, in the Independent Consumer and Competition Commission Act 2002 s 2 states that ‘Commission’ means the Independent Consumer Commission and Competition . . .’ Thus, ‘Commission’ in this legislation refers to the PNG Consumer and Competition and no other commission.

- ‘Includes’ expands or clarifies the ordinary meaning of a defined word by giving examples - for example, in s 2 of the Independent Consumer and Competition Act 2002, ‘decision’, when used as a verb, ‘includes . . . declaration, determination, order, or other decision . . .’. The draftsperson has attempted to enlarge the ordinary meaning of ‘decision’ using the word ‘includes’ and the examples that follow.

‘And’ versus ‘or’

The words ‘and’ and ‘or’ are commonly found in Acts, regulations, and legal documents.

- ‘And’ is used when the draftsperson wants the words or phrases to be read together. All the matters or facts listed must exist, or if it is a requirement, all of them must be satisfied.

- ‘Or’ is used to split words or phrases. The importance of the distinction between the two words is illustrated in s. 130(6)(b) of the Independent Consumer and Competition Act 2002, where the section states that a person who ‘wilfully furnishes false or misleading records. . .’ is guilty of an offence. The effect of ‘or’ is to make it an offence if you furnish false records, and similarly, if you furnish misleading records. Remove ‘or’ and substitute with ‘and’ and you can see the difference because now there are two requirements to satisfy.

‘May’ versus ‘might’

- The use of the word ‘may’ in an Act or regulation used in relation to a duty or power should suggest to you that the duty or power is discretionary, not mandatory, that is, there is a likely possibility that the duty or power will be exercised but it may not be.

- ‘Might’ indicates an unlikely possibility that something is not happening and is the past tense of ‘may’.

‘Will’, ‘shall’ and ‘must’

The use of the words ‘will’, ‘shall’, and ‘must’ in an Act or regulation are all used as verbs to express an obligation. Context is important and you need to consider three principles when you come across one of these words in an Act or regulation (or in correspondence such as a commercial contract):

- What is the natural and reasonable meaning of the sentence or clause?

- What did the parties intend?

- What makes the most sense in an Act, regulation, or commercial contract?

‘Must’ always suggests an absolute obligation and is now commonly used in all legal documents. It means you have no choice but to do it. ‘Will’, refers to a personal promise and in a contract reflects the future tense, that is, it is predictive. It doesn’t create an obligation to perform. ‘Shall’, like ‘will’, is also predictive rather than obligatory, and future tense. It is confusing because it can mean ‘may’, ‘will’, or ‘must’ depending on the context it is being used in. But in legal drafting, it expresses a third party’s positive or negative obligations and is a command.

‘Could’, ‘would,’ and ‘should

These are the past tense of ‘shall’, ‘will’, and ‘can’

- In the case of ‘could’, this is generally used to suggest a possibility or to make a request - for example, ‘Could you please pass that book?’ ‘Could’ suggests you could do it, but you might not want to.

- ‘Would’ is used to refer to a possible or imagined situation, often used when that possible situation may not be going to happen: ‘When would you have time to read a chapter before class?’

- ‘Should’ is the conditional form of shall and implies that something ought to be done, or to express something that is probable, for example, ‘Your book should be here after lunch?’, or to ask a question, for example, ‘Shouldn’t you read this chapter before class?’

What does ‘reasonable’ mean?

Here is another word you frequently encounter in law, but do you know exactly what it means? You will encounter the reasonable person referred to on numerous occasions as you cover the materials in this subject/unit. To establish a breach of the duty of care the court must be satisfied that the risk was foreseeable, not insignificant, and what would a reasonable person have done in the circumstances.

The court will consider the meaning of ‘reasonable’ according to the circumstances and consider:

- The more serious the harm, the more likely it is that the reasonable person would take greater precautions

- The more probable the harm, the more likely the reasonable person will take precautions

- If there is little prospect of harm occurring, the more likely it is that the reasonable person will not take any precautions, and

- If the potential benefit of the defendant’s actions or inactions is greater than the risk of harm to others, a reasonable person is less likely to take precautions.

So how do the courts deal with interpreting language? They generally resort to the following rules:

- words will generally be given their normal dictionary meaning (if you come by a word you haven’t seen before, get a dictionary or look it up online)

- technical words are generally given their technical meaning

- words are interpreted according to their current meaning

- if a word is used more than once, it should be given the same meaning unless a contrary intention exists in the Act, and

- a statute should not be given retrospective effect unless expressly provided for in the statute. Parliament has the power to make laws but the problem with it is that Parliament is making a law today to apply to an act or omission that was legal when you did it yesterday. Do you think that is fair? Most legislation is proactive because it only alters the direct legal consequences of future events or actions.

The Courts

How do you find and reference a case?

If you need to find a case, there are two options: go to a law library or, much easier nowadays, use the internet and the databases online.

Online reference

Online reference

Find a case online

If you do ever need to find a case online, go to the Papua New Guinea Primary Materials on the Pacific Islands Legal Information Institute website. See also recent cases and updates for the Supreme Court, National Court, and District Court (and cases in 2022).

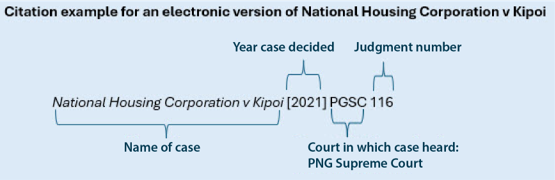

If you need to find a case, the name of the case is followed by:

- the year of publication

- the initials of the court making the decision, and

- the judgment number.

For example, if you needed to find the case of National Housing Corporation v Kipoi all you need to do is type in the name in whatever search engine you use and you will see the name and URL for the case. Click on it and you will get taken to the site for National Housing Corporation v Kipoi [2021] PGSC 116.

If the case is not available online, reference needs to be made to a set of traditional law reports. Law reports have a slightly different citation to the electronic one. Each report has its own citation, and a law librarian will be able to direct you where to find the relevant report. Try the library at the PNG Supreme Court located in Waigani, which has both a print collection and an electronic legal collection or the Law School library at the University of Papua New Guinea.

When it comes to including a case in an assignment, or an answer to a legal problem, some basic principles should be kept in mind. These include:

- The initial case name (citation) must appear in full - for example, National Housing Corporation v Kipoi (‘National Housing’). If there is no reference to a specific page in the case, and as this case now appears in an online version it would appear as: National Housing Corporation v Kipoi [2021] PGSC 116 (‘National Housing’).

- If there is a reference to a specific point in the case, the reference to the citation would be to the paragraph number and it would appear as: National Housing Corporation v Kipoi [2021] PGSC 116 at [8].

- Any further references to that case can then be in abbreviated form, as in footnote 2 here:

- National Housing, above n 1, [9].

Note: The footnote above is an example based on AGLC4 referencing style. This referencing style is not used throughout this text.

See a citation example below in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Citation example for an electronic version of National Housing Corporation v Kipoi. Image description.

Source: Gibson A (2024).

Finding the ratio decidendi (reason for deciding) and obiter dicta (sayings by the way)

It is useful to just briefly explain the meanings of two key terms that you will come across in reference to cases and there is more on this in Chapter 2 in relation to what we call precedent.

The ratio of a case is the reason for the decision. It is the reason/s for a judge’s decision in a case based on a ruling on a point of law deduced from the facts of the case as presented to the court. It is not a statement of the law. Obiter (or sayings by the way), on the other hand, are remarks made by judges that do not affect the decision in the case.

An excellent case that illustrates how these rules work is an English case called Hedley Byrne & Co Ltd v Heller & Partners Ltd [1964] AC 465 which expanded the law of negligence (what is known as a tort) to a new area of the law of negligence to include negligent misstatements, which caused pure economic loss.

If you are ever in the position of having to find either the ratio or examples of obiter (or both) in a case take the following steps:

- First, what were the parties asking the court to decide – the issues in contention?

- Secondly, read the whole judgment.

- Finally, what is the court's reasoning in determining the case's outcome?

Parliament

How do you find Acts and regulations?

As you will read in Chapter 2, the second main source of law within the PNG legal system is statute law and all three levels of government - national, provincial, and local – have legislative powers under the Constitution and the Organic Law on Provincial Governments and Local-Level Governments.

The three levels of Parliament each have their own distinct law-making powers. The powers that are not specified are assumed to remain with the national government. Provincial and local-level government powers are subordinate to the national law and have legislative power allowing them to pass legislation, but only to the extent that the national interest requires, otherwise they have relative autonomy in how they are to operate. It is worth noting that the powers of local-level governments are subject to the powers of provincial governments.

The law-making powers of the National, Provincial, and Local-Level Governments are set out in the Constitution of the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, while a list of Organic Laws can be found online at Papua New Guinea Organic Laws(the law-making powers of the Provincial and Local-Level Governments can be found in the Organic Law on Provincial Governments and Local-Level Governments).

Online resources

Online resources

Find Acts and regulations

Legislation can be found at Papua New Guinea Sessional Legislation but the best site is the National Parliament of Papua New Guinea.

If you want to find an Act or regulation, and you will find numerous references to Acts (or statutes) and regulations in business, it is useful to know how to be able to find copies. Do not rely on another person’s copy unless you are confident it is a copy of the most recent copy. Similarly, do not rely on what a person states about how or why an Act or regulations apply unless you know what they are talking about. Why? The reason for being so pedantic is that if you are relying on an Act or regulation to make your case, or to be used as a defence in court, and you have been given the wrong information because you didn’t check, you might lose the case, so always check.

In brief

In brief

Some key points to note about legislation

- Acts and regulations are made by the three levels of government in PNG (and any subordinate bodies to which the Parliaments have delegated power to legislate).

- They are supreme law.

- In the event of a conflict with the common law, statute law prevails.

- They assume the existence of common law and often reaffirm common law principles.

- They can modify or replace the common law.

- They can respond more quickly to change to meet current community needs than the common law.

- They can be made retrospective and apply back in time.

- Because of the increasing complexity of legislation, doubts about the meaning of a word, phrase, ambiguities, or the extent of the operation of the Act itself will arise.

- Their titles are proper nouns and therefore commence with a capital letter, for example, the Goods Act 1951. Similarly, the word ‘Act’ is a noun and always begins with a capital ‘A’.

How do the courts determine the meaning of an Act or regulation?

Because Acts and regulations are made up of words, you don’t give a great deal of thought to their purpose in a sentence. Remember the example above of ‘false and misleading’ versus ‘false or misleading’? Substitute ‘or’ for ‘and’ and vice versa in a paragraph and note the difference. Now, what happens with Acts and regulations? Can you have similar problems with the meaning of a section in an Act or regulations? The answer is ‘yes’. So how do the courts deal with this type of problem?

To assist the courts (and you) there are rules for interpreting legislation. It is useful knowledge to have when you are in business because of the increasing role of statutory regulation by the three levels of Parliament in PNG in how business is to be conducted.

The tools available to the courts to use when the question of statutory interpretation arises include:

- rules of statutory interpretation (see for example, s 109(4) of the Constitution of the Independent State of PNG 1975)

- Interpretation Act 1975

- maxims (or aids to construction), and

- precedent.

In Gari Baki v Allan Kopi [2008] PGNC 251, N4023 the then Deputy Chief Justice Sir Salamo Injia at [16]:3 suggested the correct approach insofar as the principles of statutory interpretation were concerned was settled:

“The Court must give effect to the legislative intention and purpose expressed in the language used in the statute. If the words used in the statute are clear and unambiguous, the Court must adopt the plain and ordinary meaning of those words. There is no need for the Court to engage in any statutory interpretation exercise. If the words are not so clear or ambiguous, the Court must construe the words in a fair and liberal manner in ascertaining their meaning and give an interpretation which gives meaning and effect to the legislative intention in the provision. The purpose of words or phrases used in question should be read and construed in the context of the provision as a whole. The Court should avoid a technical or legalistic construction of words and phrases used in a statutory provision without regard to other provisions which give context and meaning to the particular word (s) and phrases in question.”

If the meaning and intention of the legislature is clear in the statute, the courts need to do no more than give effect to those words in the context of the Act.

An example of the literal approach can be found in the English case Fisher v Bell [1961] 1 QB 394 (the citation stands for Volume 1, QB stands for Queen’s Bench and 394 the page number of that volume), at that time the Restriction of Offensive Weapons Act 1959 (UK) made it an offence for a shopkeeper to display a flick knife in a shop window, the relevant section stating ‘Any person who sells, lends or gives a flick knife to any other person commits an offence.’

The court concluded in this case that the shopkeeper was inviting people like yourself who might have been walking past the shop to make an offer if they wanted a flick knife - that is, a sale would only be made if the shopkeeper accepted your offer. So, no breach of the Act occurred because you didn’t go into the shop and make an offer to the shopkeeper. As an aside, the case was also interesting because selling a flick knife was a criminal offence and the court applied contract law to see whether an offence had occurred.

However, if the words in the Act lead to an absurdity, injustice, or repugnancy, or the words or phrases are ambiguous, vague, or uncertain, the courts today look at what the statute was intended to remedy and attempt to choose a meaning that will try and avoid an inequitable result but looking at what was Parliament’s purpose or intention in passing the Act or regulations in the first place.

The courts will try and interpret the words in the legislation in a way that will help the legislation achieve its purpose where - for example, a literalist approach may leave the words ineffective and defeat the purpose of the legislation. The purpose rule was given pre-eminence by s 39(2) of the National Constitution, directing the courts to consider the objects and purposes of an Act when interpreting its provisions.

An example of a section of an Act that, because of the way it was drafted, caused problems in applying it was the English case of Lee v Knapp [1967] 2 QB 442. Lee was involved in a motor vehicle accident. He briefly stopped and then, seeing no one was injured, drove off. Section 77(1) of the Road Traffic Act 1960 (UK) read:

‘If in any case, owing to the presence of a motor vehicle on a road, an accident occurs whereby … damage is caused to a vehicle … other than that motor vehicle the driver of the motor car shall stop’

What do you think? Did Lee breach the section? Does a literal reading give you a sensible result? What was the purpose of the section or intention of Parliament?

The UK Parliament repealed the Road Traffic Act 1960 (UK) in 1988 with the Road Traffic Act 1988 (UK). It now requires that a driver involved in an accident has a:

-

"Duty to give a name and address

- 168. Failure to give, or giving false, name and address in case of reckless or careless or inconsiderate driving or cycling

-

Duty in case of accident

- 170. Duty of driver to stop, report accident and give information or documents

-

Other duties to give information or documents

-

171. Duty of owner of motor vehicle to give information for verifying compliance with requirement of compulsory insurance

-

172. Duty to give information as to identity of driver etc in certain circumstances."

-

Is the Road Traffic Act 1988 Act clearer to you now than the Road Traffic Act 1960 Act? Can you find similar legislation in PNG? Don’t forget to check not only for relevant statutes but also regulations such as the PNG Road Traffic Rules – Road User Rules 2017.

One final comment on Acts and regulations is that they generally carry their own definitions of terms. They are set out in a definition section that appears either at the beginning of the Act or regulation at the end as a Schedule. These are often terms that recur throughout the various sections of the statute and that the draftsperson felt needed clarification.

The use of extrinsic evidence

The courts may refer to extrinsic (external) material in the interpretation of provisions of Acts and regulations, such as:

- parliamentary debates

- headings, margin notes and end notes of the legislation under scrutiny

- reports of Royal Commissions, Law Reform Commissions and committees of inquiry that have been tabled in Parliament

- treaties or other international agreements referred to in the Act

- any explanatory memorandum attached to the bill

- any document declared by the Act to be relevant, and

- anything recorded in the official reports of the proceedings of Parliament.

Maxims

Maxims are not rules of law but, rather, are aids or guides to construction. While the draftsperson tries to define words in such a manner that every possible interpretation is covered, no definition can be exclusive or perfectly describe a class of people, things or acts.

There are several maxims available to help the courts determine the meaning of a word or phrase, although the all-important matter is to consider the purpose of the legislation. Two of the more important maxims are:

- noscitur a sociis (‘it is known from its associates’), and

- ejusdem generis (‘of the same kind, class, or nature’).

Noscitur a sociis

Noscitur a sociis, or the context rule, means that the words of a statute are to be construed in the light of their context. For example, in the English case of R v Ann Harris (1836) 173 ER 198, the words ‘If any person unlawfully and maliciously shall shoot at any person, or shall, by drawing a trigger, or in any other manner, attempt to discharge any kind of loaded arms at any person, or shall unlawfully and maliciously stab, cut, or wound any person with intent in any of the cases aforesaid to maim, disfigure, or disable such person or to do some other grievous bodily harm to such person . . .’ were considered by the court to cover only wounding by a weapon, not by hands or teeth. Any comment on the decision?

Ejusdem generis

Ejusdem generis is a subset of the rule noscitur a sociis and is known as the class rule. This rule is used to find a viable meaning for a broad, general word, such as ‘building’, when that word follows a group of more specific words - for example, ‘any house, flat, villa, unit or other building’ - and is based on context. In this case we can say that the principle of ejusdem generis applies. The word ‘building’ is limited to the same class as that which precedes it—here, places where people live. All the specific words preceding a general word must form a class. Thus, a reference to ‘any plant, root, fruit or vegetable production growing in any garden’ does not extend to trees, since there is no class here.

The class rule cannot be used:

- to find the meaning of a word that is of a specific nature

- unless there are two or more specific words before the general word.

Thus, in the case of the phrase ‘any flat or other building’, the class rule does not apply, as ‘flat’ on its own does not form a class.

Dictionaries

If a word is not defined in the definition section of an Act or regulations, a dictionary can be referred to - for example, search the university library catalogue for an online dictionary or use any hardcopy dictionary you have.

How do you write a good law essay or answer to a problem question?

An essay is a common type of assessment for a unit like Business Law. This resource offers tips and resources to help you plan and write law essays. There are usually two types of law essays: the problem-style essay and the theoretical based essay.

The theoretical based essay may ask you to critically discuss a new piece of legislation or a recent case in relation to existing laws or legal principles. You may also be asked to take a side in an argument or discuss the wider societal implications of a legal outcome.

Problem-style essays require you to advise a party based on the analysis of a scenario or given problem. You will be required to identify the legal issues and apply relevant law.

Problem questions and essays

Begin by making sure you understand the question. It sounds obvious but read the question a couple of times and if you are still not sure please ask your tutor for assistance.

As you read the question, consider the following points (and use a highlighter to mark up what you consider to be key issues):

- Read the lecturer’s instructions before you start to look at the question and note down:

- the due date, and

- the word limit. If you go over the word limit you may get penalised; if you go too far under there is a possibility that you haven’t covered everything.

- What is the question asking you to do, for example, critically analyse, discuss, explain? Is it an essay or problem-based question?

- Think about what general area/s of law the question is focussed on? An essay question will tell you, but a problem-based question will leave you to work out what the relevant area of law is.

Answering a problem question or essay

In a problem question, you are normally given a fact situation and asked to explain what the legal outcome would or should be. There might be one issue or a series of issues in the one scenario. Hence the reason to read the question carefully a couple of times.

If the question is a problem question, most Universities in Australia have adopted the IRAC (Issue, Rule, Application, Conclusion) method or style. In using this method, you will:

- Identify the legal ISSUE/S that arise in the question, stating the legal conclusion that needs to be reached and connecting it to the relevant facts in the question.

- Identify and explain the relevant legal RULES that apply in this problem - that is, what general law/s or test/s apply. You are not arriving at a conclusion at this point though.

- APPLICATION of the legal rules is where you are going to explain how the legal principles (RULES) can be applied to the facts. It is not enough to state the rules. You must link the rules to the facts.

- In your CONCLUSION concisely state the outcome of each issue you identified in the problem. This is based on the application of the rules to the facts. Then provide an overall judgment. DO NOT MENTION ANYTHING NEW. Your conclusion should explain to the reader why you have come to this final judgment.

Answering essay questions

Plan the essay

Begin by making a plan. Consider the topic and make sure that you understand it. Think about what the question is asking you to do. It may be necessary to have done some reading around the topic before you can understand the issue/s. But having a plan will help you with the structure and order of discussion of the essay when you come to write it

Just as an aside, the aim of background reading is to help you understand the context of the assignment question. Begin with general sources first and then more specific ones. Take notes as you go along as that helps you to understand different arguments and issues, or information and context, relevant to the essay. And a tip here is to be sure when taking notes that you make a note of the source so that you can correctly cite it in your essay. Remember you don’t want to be accused of plagiarising.

Don’t forget that the purpose of an introduction is that it should be an outline of the structure of the essay and prepare the reader for the topic. This should include the central argument of your essay and the key arguments which will form the main part of the essay. Its purpose is to make the reader want to read on and see whether they agree with what you are going to argue.

Structuring your answer

A key element of a successful law essay is the structure. A good structure will enable you to communicate your ideas fluently and efficiently and is an important skill in business.

Make a list of key and supporting arguments and decide on their order. Generally, your essay requires an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Try and use headings and sub-headings (three to six words) in the main body of the essay for each of your supporting arguments. This helps the reader to see where you are taking them (and it helps you ensure that you have covered everything you wanted to cover).

The advantage of using sub-headings is that it not only helps in providing structure to your writing but it also provides you with a structure to follow. If you are struggling to know at this stage what the exact content for each paragraph will be, simply list relevant material you have found while reading, and list any cases and sections of statutes/regulations which may support your arguments in each paragraph.

Try and have one idea per paragraph and aim to keep the paragraphs shorter than what you probably would have written in high school or other Faculties.

Conclusion

Do not introduce any new material into your Conclusion. The Conclusion reviews what you have written for the question. It should begin by rephrasing or restating the main argument/s of the essay but in a different way. It summarises the essay’s main arguments, gives final thoughts about the topic, and provides closure for the reader. If you are struggling to write an Introduction, try writing the Conclusion and then writing the Introduction last.

Achieving success

In order to do well, plan your work so that you can complete the final draft a few days before it is due for submission. This gives you time to ensure that your essay reflects good academic standards and is not an example of last-minute hasty work. Make sure footnotes are included, citations are correct, headings and subheadings are appropriate, that the essay is in ‘plain English’, and that there are no grammar or spelling mistakes.

Always try and get a third party to proofread your work before you submit it. When we proofread our own work, we often don’t see spelling or grammatical errors because we are seeing the text from our memory and not what is written in front of us. Get a friend to check your work for you.

Markers highly value closely edited and proofed work. Poor grammar and/or spelling mistakes can be extremely costly as the marker has to struggle to understand what the writer is saying. A lot of marks can be lost here. Good students write in clear and concise English that is easily understood.

Summary

Summary

This introductory chapter was originally intended to be a brief chapter on helping you navigate your way through a range of commercial law topics that you need to have an understanding of if, first, you want to pass easily, and secondly, which you can use later on in business or your personal life.

The problem was that to understand areas such as negligence (a tort), contract law, consumer protection and agency you really needed to understand that reading is terribly important. The more you read, the better you will understand. But even while the more reading you do is great, you must also understand the importance of the use of words like ‘and’ and ‘or’, ‘must’ and ‘may’, and so on, and as you read you can appreciate their importance.

You also need to understand where the law comes from, hence the reason why we have included a commentary on the courts and help with how to find a ratio and obiter as they form the basis of common law, as well as how to interpret Acts and regulations.

What you need to understand at the end of the day is the role law plays in your lives and that ignorance of the law is no excuse.

Reference list

Gibson A (2024) Citation example for an electronic version of National Housing Corporation v Kipoi [Figure 1].

Image descriptions

Figure 1 image description: Citation example for an electronic version of National Housing Corporation v Kipoi. The Name of Case is National Housing Corporation v Kipoi; the Year the case decided is [2021]; the Court in which the case is heard is PGSC, which stands for Papua New Guinea Supreme Court and; the Judgement number is 116. Return to Figure 1.