6 Intention to Create Legal Relations

Learning objectives

Learning objectives

On completion of this Chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain the need for legal intentions in contracts.

- Explain what intention to create legal relations means.

- Explain how the courts determine intention to create legal relations.

- Distinguish between non-commercial and commercial agreements.

Key terms

Key terms

Here are some terms you will encounter in this chapter, which will help you to better understand this chapter:

domestic agreements – agreements made between family members and relatives where there is no intention to create legal relations.

-

- Objective test: would the words or conduct of the parties lead a reasonable person to believe, on the balance of probabilities, that legal relations were intended.

- Presumption: a belief (as the word is used here it is a reference to what the courts assume).

- Social agreements: agreements made between friends or acquaintances.

- Voluntary agreements: agreements where the parties volunteer their services, usually for no money.

Introduction

Introduction

Chapter 6 introduces you to the second element that must be present in a simple contract – that is, the question of intention between the parties to create legal relations.

The fact that you have reached an agreement with another party does not necessarily mean that a contract has been created. It is this element of intention that distinguishes a legally binding contract from other types of arrangements. Without intention, you can still have an agreement but it is an agreement that is not enforceable in a court because it is not a contract. The parties will have to rely on moral or social pressure for enforcement.

In this chapter we begin by looking at intention generally (express and implied) and then the two main types of agreement: non-commercial, and commercial or business agreements. In the case of a non-commercial agreement there is a presumption (or a belief) that the parties do not intend to create legal relations while in the case of a commercial or business agreement there is a presumption that legal relations are intended.

Step 2 – Intention to create legal relations

In Step 1 you were concerned with the issue of agreement. Was there an offer? Did the other party accept? Once you are satisfied that an agreement has been reached, you need to think about whether the agreement you entered into was legally enforceable. The fact you and the other party have reached an agreement does not necessarily mean that a contract has been formed.

For an agreement to be legally enforceable as a contract, you both must intend to create legal relations. This can be express (words, writing or conduct) or implied; but if it is not present, there can be no contract.

The question of intention is closely linked to the question of agreement which, together with consideration (see Chapter 7), will determine whether the parties have entered into a simple contract. But note that even at this stage we don’t know whether our contract that we created is valid. That can only be determined after considering the elements of capacity, consent, legality and form (these are dealt with Chapter 8, Chapter 9 and Chapter 10).

Is it difficult to determine intention?

The difficulty with determining intention is trying to work out what the parties really intended. As you will discover, the parties to a contract rarely make express reference to the question of intention.

It is only when a problem arises between the parties and one party wants to enforce their ‘rights’ that intention suddenly becomes an issue. Suddenly, the party that feels aggrieved – usually because there is money at stake – will want to know what their rights are – that is, whether there is an enforceable agreement or not.

In trying to find an answer to the question of intention, the courts (in the case of Australia, up until the Australian High Court decision in Ermogenous v Greek Orthodox Community of SA Inc [2002] HCA 8 (‘Ermogenous’) classified agreements into two categories:

- Agreements of a business or commercial nature. Here the courts had adopted an approach involving a rebuttable presumption (a legal principle that presumes something to be true until evidence is produced by the party who wishes to disprove it proves otherwise) that unless the contrary can be clearly established, it was presumed that the parties did intend to create an enforceable contract.

- Agreements of a social or domestic nature. Here there was a rebuttable presumption that the parties did not intend legal relations. For example, if you agree to meet a friend at the movies and they don’t turn up, you might be upset but you don’t usually intend to sue them for breaching their promise to you.

Where problems arise is where the consequences for the aggrieved party are much more serious (for example, in a PNG Lottery win where a ticket holder claims they bought the winning ticket with their money and the ticket bought by the group did not win anything), because now the court has to try to determine what the parties intended when making their arrangement. Did the parties intend their agreement to have legal consequences should things go wrong? This can be quite hard to determine because the parties in these types of arrangements rarely make express reference to the requirement of intention.

How do you determine intention?

Intention can be determined by considering the relevant context and the relationship between the parties and determining what inferences can be drawn from that. Look at what the parties have said, written or done as well as taking into ‘account the subject matter of the agreement, the status of the parties, their relationship to one another and other surrounding circumstances.

In brief

In brief

Intention and contracts

For an agreement to be legally enforceable as a contract, one of the conditions that must be satisfied is that the parties intended to create legal relations. Intention can be either expressed in words, writing or conduct or implied, and requires an objective assessment of the state of affairs between them; if intention is not present, there can be no contract. Proving intention can be a difficult legal process.

What form can intention take?

What is express intention?

The parties rarely make any direct or express reference to the question of intention to contract within the contract itself. Where references are made, they are generally found only in commercial (or business) agreements and they are invariably expressed in a negative way – that is, by way of terms that expressly and clearly state that the parties don’t intend to be legally bound – for example, by including wording in the agreement such as:

- ‘binding in honour only’ (these are also known as ‘honour clauses’). In the English case of Rose & Frank Company v JR Crompton & Bros Ltd [1925] AC 445, a commercial arrangement contained the following clause which made it clear that the parties did not intend to create legal relations and that the agreement was not meant to be legally binding:

This arrangement is not entered into, nor is this memorandum written, as a formal or legal agreement, and shall not be subject to legal jurisdiction in the law courts . . . but it is only a definite expression and record of the purpose and intention of the parties concerned to which they each honourably pledge themselves.

- An ‘honour clause’ was effective in the English case of Jones v Vernon’s Pools Ltd [1938] 2 All ER 626 (a case involving a lost lottery ticket) preventing any legal action being taken against Vernon’s Pools:

It is a basic condition of the sending-in and acceptance of this coupon that it is intended and agreed that the conduct of pools . . . shall not be attended by or give rise to any legal relationships, rights, duties or consequences whatsoever or be legally enforceable or the subject of litigation, but all such arrangements, agreements and transactions are binding in honour only.

or

- ‘This agreement is subject to contract’ or subject to the preparation of a formal contract of sale which shall be acceptable to my solicitor’. In both examples there may be an agreement but until a formal contract is made, the parties are not bound. The key word is ‘subject’ and it tells a court that there is still more to be done, as in, a formal contract has to be made.

Parties to a contract may be content to be bound immediately and exclusively by the terms on which they had agreed. However, they may also decide to add some additional or further terms at a later date. A legally binding contract can still exist even though there is an intention to expand on it to substitute other terms if and when the need arises.

Can the parties exclude the jurisdiction of the courts?

The parties to an agreement can expressly declare that they don’t intend to create legal relations. What they cannot do is make a binding contract and expressly exclude the jurisdiction of the courts as this is contrary to public policy – for example, by using wording such as:

In respect of any matter arising out of this agreement or any breach thereof the parties hereby acknowledge that the jurisdiction of the court is to be excluded.

Business tip

Business tip

Word your contracts carefully. The use of words such as ‘subject to contract’ suggests to a court that the parties don’t intend to be bound immediately. However, it is still important to look at the agreement as a whole when trying to determine whether the parties intended a binding agreement or not.

If either of the parties don’t intend to create any legal obligations, then correspondence between the parties should clearly state that legal relations are not intended.

Take care to avoid using terms that might be construed as an indication of a binding agreement – such as ‘binding commitment’. Use expressions such as ‘subject to contract’.

What is implied intention?

As noted above, the parties rarely say anything about the issue of intention. It is usually only when a dispute arises that the court tries to determine what the parties intended from their words and/or actions. The central legal question is: Was the agreement intended to be legally enforceable? Unfortunately, this is rarely obvious from the agreement itself.

The question to consider when trying to determine intention is what inferences would a reasonable person have drawn from the words or conduct of the parties, having regard to all the circumstances? If a reasonable person assumes that there is no intention by the parties to be bound, then there is no contract.

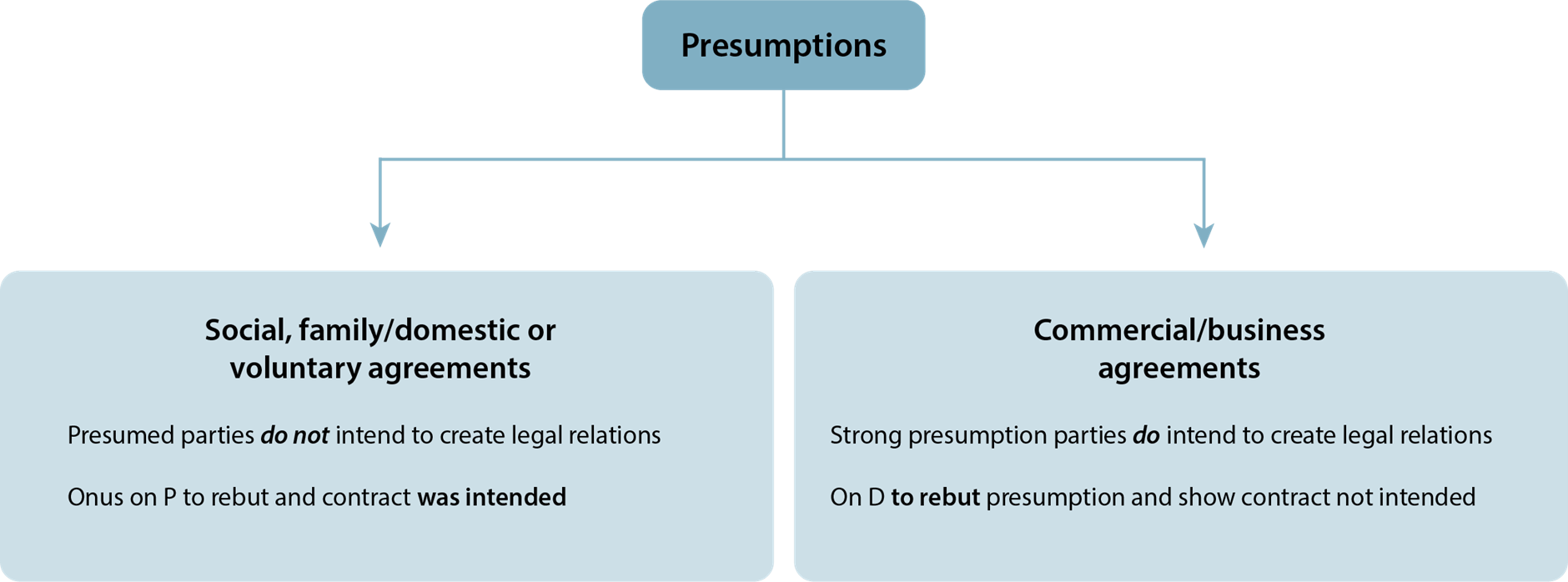

To assist in trying to determine what it was that the parties intended, the law has treated agreements as falling into one of two categories:

- social, family/domestic or voluntary agreements (non-commercial arrangements); or

- commercial or business agreements.

Traditionally, the determination of intention was then resolved by reference to rebuttable presumptions of fact. In the case of social, family/domestic or voluntary agreements, the law assumed, or presumed that the parties didn’t intend their agreement to have any legal consequences if it was not performed as the agreement is unenforceable. In the case of commercial/business agreements, it was assumed, or presumed, that the parties did intend to create legal relations.

Figure 2: Chart explaining the presumption between parties. Image description.

Source: Gibson A (2024).

In both classes of agreement, in determining intention reliance was placed on applying a presumption. The presumption would not apply if one of the parties could produce sufficient factual evidence to satisfy a court, using an objective test involving a hypothetical person, that the agreement was intended (or not intended, depending on the class of agreement) to be binding. That is, what inferences would a reasonable person have drawn from:

- what the agreement says

- what the parties have said

- what the conduct of the parties was

- what were the consequences for the parties; and

- the surrounding circumstances.

If the reasonable person after considering these factors assumed there was no intention by the parties to be bound, then there would be no contract.

How has the Australian High Court approached the use of presumptions?

It is not clear whether the PNG National and Supreme Courts will follow the decision of the Australian High Court in a case called Ermogenous v Greek Orthodox Community of SA Inc [2002] HCA 8. In this case the High Court suggested that the use of presumptions was merely a useful tool to identify who should bear the onus of proof and that in every case the party asserting the existence of a legally binding agreement bears that onus of proof.

The question in every case was whether an objective assessment of the state of affairs between the parties, in the context in which they were dealing, could be said to show an intention to create legal relations. What would reasonable persons in the position of the parties have understood to have been intended?

Where there is payment of money as consideration for a promise by the other to provide some service or bestow some benefit, the conclusion that can be drawn is that each intended the promise to be taken seriously.

In Ermogenous the question of whether the parties could objectively be seen to intend to create legal relations could include:

- the subject matter or topic of the agreement

- the status of the parties

- their relationship to one another

- whether there is a consensus among the contracting parties

- the extent to which it is expressed to be finally definitive of their concurrence

- the way the agreement came into existence

- subsequent conduct or communications between the parties; and

- any other surrounding circumstances.

In a large number of cases the results will be the same as if the agreement had fallen into the presumption categories: commercial/business or social, family/domestic, and voluntary or Ermogenous.

Commercial or business agreements

Commercial or business agreements make up the majority of litigated disputes and there is a strong inference in such cases that the parties intended to create legal contractual relations. This is particularly true where the parties are both corporate entities. The relationship between the parties then is going to be a relevant matter in determining whether they had an intention to enter into legal relations.

While there is initially a strong inference that legal relations are intended in commercial or business dealings, if the parties want to show that they didn’t intend to create legal relations they need to show, using clear wording such as ‘…subject to preparation of a formal contract…’or ‘binding in honour only…’, that they didn’t intend to create legal relations notwithstanding the commercial nature of the agreement.

What is the intention of the parties using a ‘letter of comfort’?

In order to secure a loan, a bank or lending institution will try to seek a guarantee from a parent company and, if possible, from the subsidiary company to which the loan is made. This is the only way the lender can be certain that assets of the group will be available to meet the obligations of the borrower should there be a default on the loan. Where the loan is supported by a contract of guarantee, there is no problem with intention. The liability of the guarantor arises on default of the subsidiary.

But it often happens that a parent company will refuse to give a guarantee – for example, because it does not want a contingent liability to show up on its balance sheet, or it might just not want to be a guarantor. In such a case, a compromise is a letter of comfort.

A letter of comfort may take the form of an undertaking to maintain its financial commitment in the subsidiary, or it may be one where the parent company agrees to use its influence to ensure the subsidiary meets its obligations, or it may be nothing more than an acknowledgment by the parent company that a subsidiary has entered into a contract.

In this type of commercial transaction, it is always going to be assumed that the parties intended legal relations, unless it can be rebutted by a clear statement to the contrary. However, whether a statement is seen as promissory or a statement of intention is a matter of construction and taking into account the parties’ acts and conduct, including statements they made and documents they signed or dealt with, whether there is a clear indication of what they intended.

Do government ‘contracts’ always result in contractual relations?

While governments and government departments enter into contracts on a daily basis, there are some types of government dealings that simply don’t result in the creation of contractual relations. These usually involve some aspect of the government’s political or administrative activities, and here the courts are more reluctant to infer an intention to create legal relations.

Where government schemes or handouts are concerned, the better view is that there is no intention to create legal relations.

What is the presumption in business advertisements?

Where advertisements are concerned, it is presumed that they are not intended to create legal relations. As usual, each case should be looked at on its facts to see whether intention is present. A good example where the courts found that the advertisements did create legal relations was Carlilll v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company in Chapter 5. The £1,000 deposited at the bank clearly evidenced an intention to pay anyone who performed the conditions of the offer and who claimed the money.

Expressions such as ‘one per customer’ or ‘rain check’ by an advertiser in a newspaper advertisement or brochure are intended to make clear to the world at large that if the advertiser runs out of a product it will get more in at the advertised price for the customer. In other words, there is an intention on the part of the advertiser to be bound by the wording in the advertisement. This is where there is an offer, rather than there being an invitation to treat.

Business tip

Business tip

Ensure that advertisements accurately reflect the intention of the advertiser

In the case of advertisements, it is presumed that there is no intention to create legal relations. However, advertisers should make it clear in their advertising if restrictions are to apply use wording such as ‘subject to . . . availability’. Similarly, the use of expressions such as ‘one per customer’ or ‘rain check’, makes it clear to the world at large that the advertiser intends the customer to get the product at the advertised price if it runs out.

Reflection questions

Reflection questions

Time for a break. While you are taking a break think about the following questions on intention and again, make notes.

A. Must intention to create legal relations be present in every contract?

B. How can you tell whether an advertisement is an offer or an invitation to treat? Explain.

C. Why do you think that in most agreements of a commercial nature the law assumes that the parties intend to create legal relations?

D. Is it possible to avoid creating legal relations in a commercial/business agreement? Explain.

Do non-commercial agreements lack serious intention?

At common law it was possible to identify three types of agreements as generally lacking serious intention on the part of the parties to create legal obligations:

- Social agreements made between friends or acquaintances – for example, in relation to competitions and lotteries.

- Family or domestic agreements made between family members and relatives, not just spouses, but note that also brings into play customary law; and

- Voluntary agreements, where the parties may volunteer their services without any consideration.

In these types of agreements, the parties don’t intend to create legal relations, even though the ‘agreements’ contained promises made by the parties, preferring instead to rely on family or friendship ties of mutual trust and affection. The test is objective, based on the reasonable person with the onus on the plaintiff to produce sufficient evidence to convince a court, on the balance of probabilities, that a contract was intended.

In Australia, after Ermogenous, determining the question of intention is by way of consideration of the relevant context and the relationship between the parties, and determining what inferences can be drawn from that. However, whichever approach the court chooses to use is probably going to be the same under either approach.

Are legal relations intended between social and domestic partners?

Traditionally, agreements made in a family context had been considered unenforceable. Thus, for example, in the case of a domestic agreement made while the husband and wife were still living together or in a continuing de facto relationship, it had been presumed that the parties don’t intend to create legal relations in relation to any promises they may make to each other. If they are separated at the time the agreement was reached, it is much more likely the parties intended to create legal relations.

Parties to domestic agreements are not restricted to situations involving couples in a relationship. They can extend to other family members, including brothers and sisters, aunts and uncles, nephews and nieces, and in-laws. In each case the onus is on the plaintiff to produce evidence to show that a contract was intended, and the court will look at the words and conduct of the parties to try to determine their intention. In that context, the court will be more inclined to find that intention exists if the consequences of the promise are serious for one of the parties and they have changed their position in reliance on the promise that has been made to them.

If there is ample evidence that would indicate to a reasonable person that the parties did intend legal relations, notwithstanding that the relationship between the parties was one that could be categorised as social or domestic, then the courts seem more than prepared to find that a binding and enforceable contract exists.

In PNG s 9(f) of the Constitution, customary law is recognised as an underlying part of the legal system, and power to deal with family matters such as divorce and financial claims can be dealt with through village courts applying customary law rather than the common law.

Are legal relations intended in voluntary agreements?

Participation in charitable or other voluntary organisations, where a person provides their services for free, is another situation in which the parties don’t normally intend to create legal relations.

While there is an agreement, it is usually clear from the surrounding circumstances that a contract was not intended at the time of entering into the agreement. This may not appear to be a problem at first glance, but if the person is volunteering their services for nominal or no payment and are injured, they have no right to workers’ compensation coverage under the Workers Compensation Act 1978 because it is assumed that no contract of employment was intended.

Reflection questions

Reflection questions

Time for the final break for this chapter. While you are taking a break think about the following questions on intention and again, make notes.

A. Why aren’t voluntary agreements contracts? Explain.

B. Can you list any agreements that you could enter into daily that could result in an inference that contractual relations were not intended?

C. Why do you think that in most agreements of a voluntary nature the law assumes that the parties do not intend to create legal relations?

D. Is it possible to create legally binding agreement out of a social or family relationship? Explain why.

E. In the agreements that you enter into, do you consider the question of intention? Explain why.

Key points

Key points

An understanding of the following points will help you to better revise material in this section on Intention.

- Why is legal intention needed in contracts? The issue of intention assists the court in determining whether or not the parties have reached an agreement that they intend to be legally enforceable.

- What is the effect of a lack of an intention to an agreement? Agreements without intention are agreements that are not enforceable in a court of law.

- Can the parties exclude the jurisdiction of the courts? The parties can expressly state that they do not intend to create legal relations, but they cannot make a binding contract and expressly exclude the jurisdiction of the courts.

- What is the difference between express and implied intention? Express intention is where the parties make direct or express reference to the question of intention in the contract by way of a term. Generally, express intention is found only in commercial or business agreements.

- Implied intention, on the other hand, arises where the intention of the parties is not expressly stated. Here, the court has to try to determine from their words and/or actions whether the parties intended legal relations.

- What is the difference between non-commercial agreements and commercial agreements? In non-commercial agreements – that is, family or social arrangements, or voluntary agreements – the type of agreement is usually lacking serious intention on the part of the parties to create legal obligations. The onus is on the plaintiff to establish that the parties did intend legal consequences from their agreement.

- In a commercial (or business) agreement the court assumes that, unless the contrary can be shown, the parties usually intend to create legal relations. Thus, the onus is on the plaintiff to show that legal relations were not intended.

- What is the Ermogenous approach to the use of presumptions? The question to consider is whether, on an objective assessment, reasonable persons in the position of the parties would have understood what was intended.

- What is a letter of comfort? A letter of comfort is a document of assurance issued by a parent company to reassure a subsidiary company of its willingness to provide financial support or use its influence to ensure that the subsidiary meets its obligations, or to acknowledge that a subsidiary company has entered into a contract.

- What is a voluntary agreement? A voluntary agreement is an agreement where the parties normally don’t intend to create legal relations.

Image descriptions

Figure 2 image description: Presumptions chart explaining social, family/domestic or voluntary agreements do not intend to create legal relations. Strong presumption parties such as commercial and business agreements do intend to create legal relations. Return to figure 2.