9: Data extraction

Data extraction refers to the information taken from each included paper. This should include key information about the study (author(s) name, publication year), important methodological contexts (study design or study aim, details of the study participants) and key components of the research question or research objectives.

You will need information to answer your research question, so PICO components should be covered. References to all included studies should appear at the end of the review.

It is common to compile the information extracted from the included studies into a table. In this book, we refer to these data tables as grids. Such grids provide a useful way to visualise and eventually summarise the data. Section 10: Interpreting the findings discusses this further.

Grids should be as succinct as possible, and at the same time include all relevant information. There are two main challenges to setting up an effective grid. The first is working out the columns that you will need, and the second is working out how to fit the data into the grid without it becoming too long or too overwhelming. You can find examples in Table 2a and Table 2b and a further discussion of these below.

Some research questions will allow a mix of study designs, but others will not. You need to think about how quantitative and qualitative studies could contribute to answering your research question. For example, if the research question is to identify different types of responses to statistical anxiety, both quantitative and qualitative studies could be used to answer this. You also need to think about what you will do if the information you have decided is important to answer your research question isn’t reported in the included study paper.

- If you include only quantitative studies in a review, you will need to report any numerical results (including their 95% CI or p-value), even if no meta-analysis is performed.

- It helps to report studies by study design. Report all cross-sectional studies together, all cohort studies together and so on. Meta-analysis, or statistically combining results from more than one study, may be possible, but you will likely need to get advice from a statistician on this.

- If you include only qualitative studies in a review, you will need to report the theoretical framework used to understand the phenomenon under study, the data collection and the analytical methods used.

- If you include a mix of qualitative and quantitative studies, you will need to think carefully about how to approach the interpretation of study findings. You could include descriptions of the phenomenon under study for each paper in the same column as a description of intervention or exposure.

- If a qualitative study starts out looking for specific outcomes (e.g. barriers and enablers), you can list these terms in your outcomes column. In the results column you would list what the researchers found (e.g. any themes).

Sample data table

In this example from Muhamad and colleagues,[1] Table 2 reports the theoretical, methodological and analytical frameworks used in different studies exploring the same issue.

What data to extract?

When thinking about the data to extract when conducting any review, it helps to think about the information needed in the final review report. Efforts to improve the quality of published health research literature in clinical areas include the EQUATOR Network (Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research), an international ‘umbrella’ organisation comprised of researchers, research funding bodies, medical journals and others with a shared interest in improving quality in research and research publications, largely through the development of reporting guidelines. Reporting guidelines for study designs used in clinical research areas, including systematic reviews and relative quality research studies, are available through the EQUATOR Network website.

Box 2 shows examples of commonly extracted data. These may be in separate columns or combined in ways that make a grid more concise.

Box 2: Commonly extracted data items

| Data item | Description |

|---|---|

| Study, including the first author and year | This data is to identify the included study. This is best described in terms of the last name of the first author and the year of publication. The full reference to the paper should be listed at the end of the review, and there should be sufficient information in this column to find the specific paper in the full reference list.

You do not need to include the title of the paper, as it overcrowds the table and makes it difficult to read. |

| Country/setting | Information about where the study was conducted is often highly relevant to interpreting the results of a review. It can be important to record where a study was conducted either as the country or countries where it took place or the location (e.g. hospital or community). |

| Study design | Study design is important to interpreting study findings and should always be reported in some way. You can include how data were collected, such as through a postal or online survey or through interviews or focus groups. |

| Study aim(s) | It is useful for readers of a review to know how the research question aligns with the aims of the included studies. |

| Sample size | Report the total number of study participants, and if relevant, the sizes of the intervention and control groups, or other important differences; e.g. males and females or adults and children. |

| Study participants | Relevant details of the study participants could include age range or gender, or employment status or background, depending on the research question. |

| Intervention or exposure | This data refers to what happened in the study. It could include an action, such as education or therapy, provided to study participants (or some of them), or it could be the situation that the participants were in (such as mental health crisis or exposure to a particular phenomenon). |

| Dose | If the amount of intervention or exposure is potentially relevant, this data can be recorded; e.g. this could be the number or type of education sessions. |

| Outcomes measured | Study outcomes are the variables that may change in a study; e.g. anxiety may increase or decrease. The data that needs to be reported relating to the outcomes assessed in a study includes how the outcome was measured and when; e.g. anxiety can be measured in different ways with different tools and at different points in time. Some studies may assess an outcome only once, whereas other studies may use multiple assessment points. |

| Results | The findings or results of a study (sometimes also called the study outcome, just to make things confusing) should be reported. Ideally you would include any relevant numerical data found in quantitative studies (with the corresponding confidence intervals) and any relevant themes from qualitative studies. |

| Author conclusions | It can be useful to include a brief summary of the conclusions that the authors made. This can be especially helpful if the results are not conclusive. |

| Limitations | As you are extracting data from a study it is helpful to document any reported limitations and any limitations that you observe. This information can be used when writing up the review findings. You need to clearly note who identified the limitations. |

| Study quality | Report your judgement of the critical appraisal for each included study. Again, this can be useful when writing up the review findings. |

Data extraction grids

Table 2a and Table 2b are examples of different ways to use grids. They are from a data extraction activity based on a review looking at the effectiveness of art therapy.[2]

This example addresses a question of effectiveness, so all included studies are randomised controlled trials, and this information is included in the table title. This means that these grids don’t need a column for the study design but, as you will see, include sample size and the sizes of the control and intervention groups.

Published reviews do not always include the information that you might expect. In this example, estimates of effect size are not reported. If enough information is reported from a study, it may be possible to calculate parameters such as these. It is helpful to be aware of what isn’t reported when reading any study.

In the second example (Table 2b), the description of the study participants and sample sizes are combined, and details about the amount of therapy and outcomes measured are grouped within each cell to show where information may be incomplete. In this example the results column is not shown.

Data synthesis

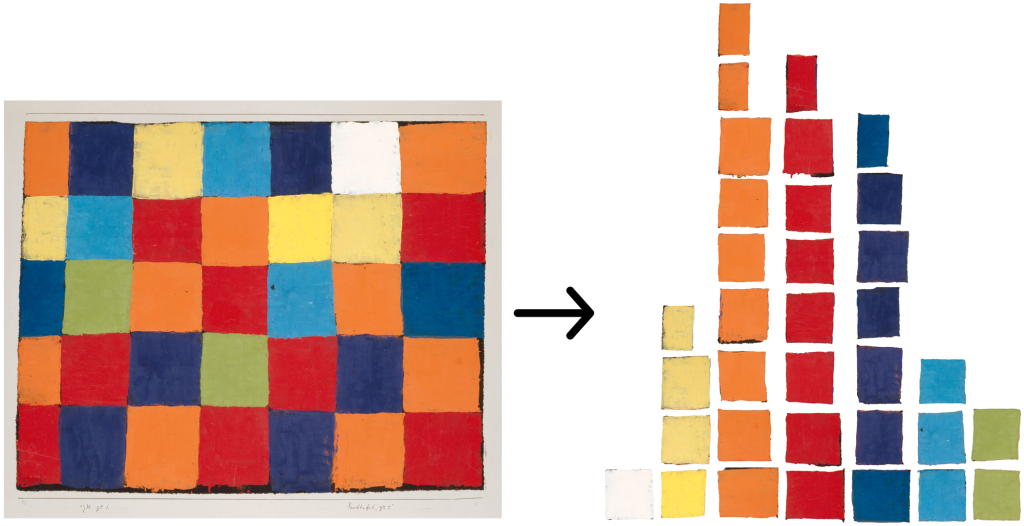

Reviews provide a way to pull together similar data from different sources to create an ordered way to look at the information. Figure 2 shows visually how information across a range of studies can be collated into component data parts. The first step in doing this is to describe the data you have collated in each column of your grid. In Figure 2 this is depicted by columns built from blocks of the same colour. This visualisation is one way to think about how similar types of information taken from different sources can be grouped. The content relating to each type of information (column in the grid) should be described and summarised in a paragraph. This tells readers about the scope of the studies that have contributed to the review, which in turn is the evidence base used to answer the research question.

There are no fixed rules about exactly what to include in describing different characteristics of included studies, although there are reporting guidelines for more experienced reviewers. You can look at the EQUATOR Network to find out more about these. EQUATOR stands for “Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research”, and the Network is an international initiative to improve published health research.

The goal is to understand the need to summarise information across studies and to think about how much information should be extracted from the different studies.

The starting point for any review is to report how many and the types of studies included in the review. The best way to explain this process is to work through an example.

Example: Synthesising data

In this example we will use the art therapy review[3] used earlier.

Using the information in the grids (Table 2a or Table 2b), the included studies could be described as follows.

Four randomised controlled studies, published between 1971 and 1996, assessing the effectiveness of art therapy were included in the review.

Tips for writing narrative summaries

Still based on the information in the art therapy review, consider the following tips for narrative summaries.

Study sample

Descriptions of the study population should mention the total number (of children, 153). There is no information given about age but note that one study included adolescents and that two studies relate to school-age children. One study includes only boys, but there are no other gender breakdown. Two studies include participants with identified behavioural or health issues (Kymissis, 1996; Rosal, 1993).

The numbers in brackets under the sample size refer to the numbers in the intervention and control groups. Rosal (1993) had two intervention groups and a control group.

Interventions used

More information from the original studies would make it easier to write an effective summary. Here we must assume that all interventions have been judged to be art therapies (ideally you would check how this was done and include a description of the process used).

Descriptions of the intervention could mention several things:

- Amount of therapy (the dose). You could categorise the dose in several ways. For example, you could calculate the number of sessions in each study or the number of sessions per week. You could also compare the length of each session and the duration of the different programs.

- What the intervention is compared with.

Outcomes measured

All of the studies use different scales. In the two studies with participants with identified behavioural or health issues (Kymissis, 1996; Rosal, 1993) these scales focus on health and behaviour assessments, whereas the other two studies focus on self-evaluations.

Results

Two studies found no significant effects; these were both studies involving participants with behavioural or health issues. Two other studies found improved self-evaluations in terms of self-esteem and self-concept. No numerical outcomes are reported so the effect size cannot be reported.

Reframing data

Different studies don’t always present data in the same way. Sometimes you need to think whether you will need to transform the information in some way so that you can compare it more effectively.

Example: Reframing data

It is common for studies to present similar data in different ways, which can make comparison across studies difficult. In the art therapy example, the amount of therapy is presented quite differently in the four included studies (see Table 2a), which limits how this aspect of the intervention can be compared. However, it is sometimes possible to overcome problems like this by thinking about how the same information could be presented in a way that would enable more meaningful comparison. In Table 3, descriptions of the amount of therapy were considered in terms of the total number of sessions and the number of sessions per week, thus showing how this might reframe the amount of therapy.

Table 3: Equivalence alternatives for amount of therapy in the Reynolds et al. systematic review of randomised controlled trials

| Equivalences that could be used | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount of therapy | Total no. of sessions | No. of sessions per week | Session length | Art therapy ‘dose’ in minutes | |

| Kymissis 1996 | 2 weeks, 4 meetings per week | 8 | 4 | Not specified | Cannot be calculated |

| Omizo 1989 | 10 sessions, 45–60 minutes each | 10 | Cannot calculate as no information about length of program | 45–60 minutes | 450–600 minutes |

| White 1971 | 8 weeks, 5 days per week for at least 90 minutes | 40 | 5 | At least 90 minutes | At least 3,600 minutes |

| Rosal 1993 | 10 weeks, twice weekly for 50 minutes | 20 | 2 | 50 minutes | 1,000 minutes |

This reframing allows for a summary of the amount of therapy.

The amount of therapy varied in terms of the number of sessions (from 8 to 40) and their duration (from 45 to 90 minutes), although session length was not specified in one study (Kymissis, 1996). This indicates that for the three studies where this can be calculated (Omizo, 1989; White, 1971; Rosal, 1993) there was considerable difference in the amount of art therapy offered (from 450 to over 3,600 minutes). The duration of the art therapy programs offered varied from two to 10 weeks, giving session frequencies that ranged from two to five per week, where this was possible to determine.

This exercise only allows us to make limited judgements regarding the effectiveness of art therapy based on the data provided. However, this is useful as it could lead to recommendations from the review for future studies, including guidelines for how art therapy programs are developed or described or determining consistent time points for outcomes to be measured (e.g. longer programs could assess outcomes at more than one time point).

- Muhamad, R., Liamputtong, P., Horey, D. (2023). Researching female sexual dysfunction in sensitive populations: Issues and challenges in the methodologies. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of social sciences and global public health. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96778-9_107-1 ↵

- Reynolds, M. W., Nabors, L., & Quinlan, A. (2000). The effectiveness of art therapy: Does it work? Art Therapy, 17(3), 207-213. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2000.10129706 ↵

- See Reynolds et al. (2020). ↵

- See Reynolds et al. (2020). ↵

- See Reynolds et al. (2020). ↵

Use of statistical methods to combine data from studies included in a systematic review. https://latrobe.libguides.com/systematicreviews

Process for judging the quality of a research paper. https://latrobe.libguides.com/criticalappraisal